Can Cartoons Which Depict Autistic Characters Improve Attitudes Towards Autistic Peers?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Big Dreams Sparked by a Spirited Girl Muppet

GLOBAL GIRLS’ EDUCATION Big Dreams Sparked by a Spirited Girl Muppet Globally, an estimated 510 million women grow up unable to read and write – nearly twice the rate of adult illiteracy as men.1 To counter this disparity in countries around the world, there’s Sesame Street. Local adaptations of Sesame Street are opening minds and doors for eager young learners, encouraging girls to dream big and gain the skills they need to succeed in school and life. We know these educational efforts yield benefits far beyond girls’ prospects. They produce a ripple effect that advances entire families and communities. Increased economic productivity, reduced poverty, and lowered infant mortality rates are just a few of the powerful outcomes of educating girls. “ Maybe I’ll be a police officer… maybe a journalist… maybe an astronaut!” Our approach is at work in India, Bangladesh, Nigeria, Egypt, South Africa, Afghanistan, and many other developing countries where educational and professional opportunities for women are limited. — Khokha Afghanistan BAGHCH-E-SIMSIM Bangladesh SISIMPUR Brazil VILA SÉSAMO China BIG BIRD LOOKS AT THE WORLD Colombia PLAZA SÉSAMO Egypt ALAM SIMSIM India GALLI GALLI SIM SIM United States Indonesia JALAN SESAMA Israel RECHOV SUMSUM Mexico PLAZA SÉSAMO Nigeria SESAME SQUARE Northern Ireland SESAME TREE West Bank / Gaza SHARA’A SIMSIM South Africa TAKALANI SESAME Tanzania KILIMANI SESAME GLOBAL GIRLS’ EDUCATION loves about school: having lunch with friends, Watched by millions of children across the Our Approach playing sports, and, of course, learning new country, Baghch-e-Simsim shows real-life girls things every day. in situations that have the power to change Around the world, local versions of Sesame gender attitudes. -

Proceedings of the World Summit on Television for Children. Final Report.(2Nd, London, England, March 9-13, 1998)

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 433 083 PS 027 309 AUTHOR Clarke, Genevieve, Ed. TITLE Proceedings of the World Summit on Television for Children. Final Report.(2nd, London, England, March 9-13, 1998). INSTITUTION Children's Film and Television Foundation, Herts (England). PUB DATE 1998-00-00 NOTE 127p. AVAILABLE FROM Children's Film and Television Foundation, Elstree Studios, Borehamwood, Herts WD6 1JG, United Kingdom; Tel: 44(0)181-953-0844; e-mail: [email protected] PUB TYPE Collected Works - Proceedings (021) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC06 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Children; *Childrens Television; Computer Uses in Education; Foreign Countries; Mass Media Role; *Mass Media Use; *Programming (Broadcast); *Television; *Television Viewing ABSTRACT This report summarizes the presentations and events of the Second World Summit on Television for Children, to which over 180 speakers from 50 countries contributed, with additional delegates speaking in conference sessions and social events. The report includes the following sections:(1) production, including presentations on the child audience, family programs, the preschool audience, children's television role in human rights education, teen programs, and television by kids;(2) politics, including sessions on the v-chip in the United States, the political context for children's television, news, schools television, the use of research, boundaries of children's television, and minority-language television; (3) finance, focusing on children's television as a business;(4) new media, including presentations on computers, interactivity, the Internet, globalization, and multimedia bedrooms; and (5) the future, focusing on anticipation of events by the time of the next World Summit in 2001 and summarizing impressions from the current summit. -

Interactive Games – Sesame Tree Some Children May Find It More Fun

Interactive Games – Sesame Tree Some children may find it more fun to work in pairs and may benefit from partner discussion. Game Aim/Synopsis Learning Outcomes Leaf Litter Aim: Curriculum Relevance: Provides the learner with an awareness of a tree as Jamie/Warren insert screen shots being a ‘home’ to a rich ecosystem of many plants, • Similarities and differences between for each activity. animals and organisms co-existing in an community groups interdependent natural community. Skills: Level 1 - invites the learner to help ‘Hilda’ • Observation investigate the ‘World of Hidden Minibeasts’ • IT: simple mouse rollover manipulation that can be found at the base of the Sesame Tree. • Literacy (new vocabulary) • Thinking skills Level 2 – builds on previous activity by encouraging • Numeracy: Number the child to find and ‘Count the Minibeasts’ – number ranges:1-5 and 6-10. The activity is designed to cater for children with limited mouse skills. This activity offers a Switch option for ‘Switch Users’. 1 Game Aim/Synopsis Learning Outcomes Scrapbook Aim: Curriculum Relevance: Encourages an awareness of habitats and • Importance of keeping healthy organisms, and what conditions are required in • Responsibilities to self and others order for them to survive. • Similarities and differences between groups of communities One Level: Hilda is upset she has knocked over • Learning to live as a member of a Potto’s Scrapbook and all the photographs have community got mixed up. Hilda invites the learner to help her Skills: match the right photograph to the correct habitat, Thinking Skills creature and food. Numeracy: sorting; patterns and relationships IT: mouse skills: drag and drop Science: observation; similarities and differences Plant a Forest Aim: Curriculum Relevance: Encourages an awareness of Art & Design. -

UNIVERSITY of the PHILIPPINES Bachelor of Arts in Communication

UNIVERSITY OF THE PHILIPPINES Bachelor of Arts in Communication Research Nicolle S. Timoteo Princess Rocel A. Uboñgen Seeing Children’s TV (SEECTV): The Values Presentation of the Children’s Shows of ABS-CBN2, GMA7 and TV5 Thesis Adviser: Professor Lourdes M. Portus, PhD College of Mass Communication University of the Philippines DIliman Date of Submission April 2012 Permission is given for the following people to have access to this thesis: Available to the general public Yes Available only after consultation with author/thesis adviser No Available only to those bound by confidentiality agreement No Student‘s signature: Student‘s signature: Signature of thesis adviser: UNIVERSITY PERMISSION We hereby grant the University of the Philippines non-exclusive worldwide, royalty-free license to reproduce, publish and publicly distribute copies of this thesis or dissertation in whatever form subject to the provisions of applicable laws, the provisions of the UP IPR policy and any contractual obligations, as well as more specific permission marking on the Title Page. Specifically we grant the following rights to the University: a) to upload a copy of the work in these database of the college/school/institute/department and in any other databases available on the public internet; b) to publish the work in the college/school/institute/department journal, both in print and electronic or digital format and online; and c) to give open access to above-mentioned work, thus allowing ―fair use‖ of the work in accordance with the provisions of the Intellectual Property Code of the Philippines (Republic Act No. 8293), especially for teaching, scholarly and research purposes. -

SUPPORT MATERIAL for WEBSITE Sesame Tree Target Age

SUPPORT MATERIAL FOR WEBSITE Sesame Tree Target Age Group: 3-6 Year olds Note on abbreviations Areas of Learning: PD&MU: Personal Development and Mutual Understanding WAU: The World Around Us Arts: The Arts Skills and Capabilities: TS&PC: Thinking Skills and Personal Capabilities COMM: Communication UM: Using Maths UICT: Using ICT bbc.co.uk/ni/schools/sesametree 1 ACTIVITY PLANNER 1 TIDY UP AND RECYCLE Activity Planner SUGGESTED LEARNING INTENTIONS Children will o Listen to and take part in discussions and communicate information, ideas and opinion(COMM); o Explore and interact with a digital environment (UICT); o Understand the need to respect and care for their environment (WAU); o Recognise the positive contribution they can make to their community (PD&MU); o Describe how peoples actions can affect plants and or animals(WAU); and o Identify an issue of concern in the local community (WAU). CONNECTING THE LEARNING WORDS I MIGHT HEAR AND USE The World Around Us Litter, rubbish, recycle, materials, cardboard, glass, o Change over Time: How do things change? How can we make change happen? plastic, paper, tin, landfill sites and refuse. Personal Development and Mutual Understanding o Learning to live as a member of a community. SUGGESTED ACTIVITIES o Bring in a bag of shopping (use plastic carrier bags and include items with excess packaging); o Unpack the shopping and talk about the excess packaging used, the wrappers that are taken off the food before it is stored and even the damage caused to the environment and wildlife by plastic bags. Talk about what to do with the packaging once it is finished with. -

Swchildstories Spread

ANNUAL REPORT 2007 WORKSHOP SESAME SESAME WORKSHOP 2007 ANNUAL REPORT ORG . SESAMEWORKSHOP . WWW 10023 – 212.595.3456 – YORK NEW , YORK NEW – PLAZA LINCOLN ONE What began as an American phenomenon in the late ’60s is still going strong in the U.S., as well as in Egypt, India, South Africa, Kosovo and more than 120 other countries around the world. The Sesame Workshop story is a CHILDREN’ S STORY, played out millions of times a day the world over. A MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT A MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT Dear Friend, stories with us. Families like Ntlabi’s and Tamryn’s in the Limpopo and Free State provinces of South At the Workshop, we tell stories to help children Africa, where the Sesame Street coproduction, Takalani learn – learn about faraway places, about how to Sesame, is reducing the fear and stigma associated treat one another with empathy and respect, about with HIV/AIDS. Families like the Lopezes:Army Staff how to stay healthy and strong, and of course, about Sergeant Ernesto Lopez is in Iraq on his third tour letters and numbers. of duty and our Sesame Street outreach initiative is This book is a new collection of stories – not the ones helping his and other families cope with the challenges we tell, but the ones children tell us. of military deployment. We spoke with Aman who lives in a slum on the outskirts of Delhi, who finds joy This collection is about the ways in which our work and learning in the Indian version of Sesame Street, affects the life chances, experiences and opportunities – Galli Galli Sim Sim. -

Sesame Workshop Annual Report.Pdf

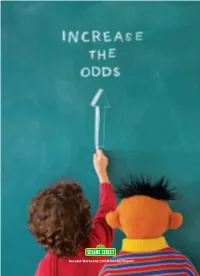

Sesame Workshop 2008 Annual Report If children experience the joy of learning, it’s more likely they’ll be lifelong learners. If they learn healthy habits, it’s more likely they’ll grow up healthy and strong. If they gain a sense of themselves and an appreciation of others, it’s more likely they’ll engage others with respect and understanding. It’s that simple and that complicated. Sesame Workshop is using the power of media – and the power of Muppets – to increase the odds that all children reach their highest potential, and in so doing, make a better world for us all. Disadvantaged children in the United States learn 15,000 fewer words by the time they reach first grade than their more advantaged peers.1 In the United States alone, Sesame Street provides the building blocks of literacy for an estimated 12 million children each week.2 1) L. Moats, Overcoming the Language Gap. American Educator, September 5-9, 2001. 2) Sesame Workshop, The Media Utilization Study, 2007. Sesame Workshop, Sesame Street Brand Tracking, 2008. Sesame Workshop is increasing the odds that children are ready to read and write, and, as a result, are ready for success in school and life. More than 60 percent of families with MAkIng ReAdIng Cool incomes of $25,000 or less report their children age 5 or younger view In January 2009, Sesame Sesame Street at least once a week.1 Workshop launched The Electric Company, a fresh take on the 1970s series of the same name. The all-new Closing the series, on television, online, and through community WoRd Gap outreach, brings literacy to life for struggling readers Sesame Street’s thirty- ages 6 to 9, especially those ninth season focuses from low-income families. -

Effects of Sesame Street: a Meta-Analysis of Children's Learning in 15 Countries☆,☆☆

Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology 34 (2013) 140–151 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology Effects of Sesame Street: A meta-analysis of children's learning in 15 countries☆,☆☆ Marie-Louise Mares ⁎, Zhongdang Pan 1 Department of Communication Arts, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 821 University Ave., Madison, WI 53706, USA article info abstract Article history: Sesame Street is broadcast to millions of children globally, including in some of the world's poorest regions. Received 21 March 2012 This meta-analysis examines the effects of children's exposure to international co-productions of Sesame Received in revised form 18 December 2012 Street, synthesizing the results of 24 studies, conducted with over 10,000 children in 15 countries. The results Accepted 4 January 2013 indicated significant positive effects of exposure to the program, aggregated across learning outcomes, and Available online 6 March 2013 within each of the three outcome categories: cognitive outcomes, including literacy and numeracy; learning about the world, including health and safety knowledge; social reasoning and attitudes toward out-groups. Keywords: fi Early education The effects were signi cant across different methods, and they were observed in both low- and middle- Educational television income countries and also in high-income countries. The results are contextualized by considering the effects Sesame Street and reach of the program, relative to other early childhood interventions. Meta-analysis © 2013 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. International As the most enduring exemplar of children's educational television or fail to reach minimal standards of literacy and numeracy (see programming, Sesame Street has been broadcast around the world. -

Sesame Street “

Magisterarbeit Titel der Magisterarbeit „Perspektiven für bildungsorientierte Vorschulprogramme im österreichischen Kinderfernsehen anhand des Fallbeispiels Sesame Street “ Verfasserin Evamaria Bauer, Bakk. phil. angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Philosophie (Mag. phil.) Wien, März 2011 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 066 841 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Publizistik- und Kommunikationswissenschaft Betreuerin: PD Mag. Dr. Gerit Götzenbrucker Danksagung An dieser Stelle möchte ich allen, die mich auf dem Weg zu dieser Magisterarbeit begleitet haben, ein herzliches Dankeschön aussprechen. Mein besonderer Dank gilt meinen InterviewpartnerInnen Lisa Annunziata vom „Sesame Workshop“, Thomas C. Brezina, Alexandra Schlögl und Mag. Andreas Vana vom ORF, Dr. Ingrid Geretschlaeger, Univ. Prof. Dr. Ingrid Paus-Hasebrink, Prof. Dr. Mag. Christian Swertz, Dr. Petra Herczeg, Dr. Maria Schwarz-Herda, Mag. Mari Steindl, Mag. Anu Pöyskö und Mag. (FH) Karim Saad für die spannenden Gespräche, Einblicke in ihre Tätigkeitsfelder und ihre fachliche Einschätzung, die diese Magisterarbeit sehr bereichert haben. Weiters bedanke ich mich bei meiner Betreuerin, PD Mag. Dr. Gerit Götzenbrucker, für den Freiraum, mich einer Thematik zu widmen, die mir persönlich sehr am Herzen liegt. Ebenso danke ich meiner Familie, deren Unterstützung und Verständnis es mir ermöglicht haben, mit viel Energie und Freude an der Magisterarbeit zu schreiben. Meiner Mutter, Lidwine Bauer, danke ich für ihre große Geduld, die aufmunternden Worte und den bedingungslosen Einsatz beim Korrekturlesen der Magisterarbeit. Herzlichen Dank möchte ich auch meinem Freund Christian aussprechen – für konstruktive Kritik, Anregungen und Denkanstöße, aber ganz besonders für den liebevollen Rückhalt während der langen Monate des Schreibens. Meiner Kollegin und guten Freundin Barbara Hauck danke ich für den anregenden und mitfühlenden Austausch auf dem herausfordernden Weg zu unseren Magisterarbeiten. -

Fund Focus Summer 2008

Fund Spring 2008 The Newsletter of the International Fund for Ireland news www.internationalfundforireland.com Fund Chairman visits Washington The Chairman, Denis Rooney, met President Bush when he visited Washington in March. He went on to hold a series of meetings with USAID, members of Congress and other parties to update them on the Fund’s recent work and to lobby for continued financial support. Meetings were held with Dr Douglas Menarchik at USAID as well as with Congressmen Richard Neal, Jim Walsh, Maurice Hinchey, Tim Murphy, Joseph Crowley and Senator Pat Leahy. He also met with senior staff of the offices of Congresswoman Nita Lowey and Congressman David Obey as well as with Pictured is from left. Mark Powell and Leah Pease at the State Department. Mr. Denis Rooney, Chairman of the International Fund for The Chairman hosted a dinner for participants of the Fund’s Ambit Programme Ireland, Father Patrick and attended a number of events including the American Ireland Fund, Reception Whyte, Taoiseach Bertie Ahern T.D at the Embassy of Ireland, the Northern Ireland Bureau Breakfast, the speakers and President Bush. lunch and the St. Patrick’s Day celebrations at the White House on March 17th. £1.1m/e1.6m for ‘Respecting Difference’ Pre-School Programme The International Fund for Ireland is to Teachers will then deliver the Programme to peace and a shared future, we have to find provide just over £1.1m/€1.6m for an pupils, with ongoing support from Early Years’ ways to help our children to embrace diversity innovative new pre-school project aimed at specialists. -

Children and Media

Children and Media Children and Media A Global Perspective Dafna Lemish This edition first published 2015 © 2015 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Registered Office John Wiley & Sons Ltd., The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK Editorial Offices 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services, and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/ wiley-blackwell. The right of Dafna Lemish to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books. Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. The publisher is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book. Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. -

SAG HARBOR ELEMENTARY SCHOOL PTA NEWSLETTER October 7, 2016 JOIN the PTA and BECOME PART of Shes [email protected] YOUR CHILD’S SCHOOL EXPERIENCE

SAG HARBOR ELEMENTARY SCHOOL PTA NEWSLETTER October 7, 2016 JOIN THE PTA AND BECOME PART OF [email protected] YOUR CHILD’S SCHOOL EXPERIENCE DON’T FORGET! - OCTO BER - 7th & 8th, HOMECOMING WEEKEND PIERSON th 10 , COLUMBUS DAY, No School th PIZZA STARTS 11 , FIRST DAY OF PIZZA SALES 12th, YOM KIPPUR, No School THIS WEEK th st rd th th 17 -21 , AFTER SCHOOL CLUBS START (3 , 4 & 5 Grades) First Pizza Tuesday: 18th, PRE-K CURRICULUM NIGHT, 6:30 – 7:30 pm th Oct. 11 , the day after RED RIBBON WEEK Columbus Day. 31st, HALLOWEEN PARADE, Main St., 1:45 pm This year’s school wide COMMUNITY BULLETIN BOARD theme is “Around the World.” One of the JOHN JERMAIN LIBRARY Sunday Games, children’s shows that is Ages 3-9, 3:30; Stories, Songs & Playtime, enjoyed all over the At our PTA meeting we elected Ages 1-4, Thu, 10:30-11:15; Lego Club, world is Sesame Street. Tuesdays, 4:00, Ages 5+; Barbie Bonanza, two new members to our Board: Here are a few ways to say Maria Eftimiades will serve as Vice Wednesdays, 4:00, Ages 3+; Playdough Time, Fridays, 4:00, Ages 3+.www.johnjermain.org Sesame Street in other parts President and Sharon Bakes will SoFo (South Fork Natural History Museum) of the world: Baghch e Simsim—Afghanistan, serve as Secretary. Thank you. Salamander Log Rolling, Family, 10/8, Sisimpur—Bangladesh, Alam Simsim—Egypt, We would also like to thank 10:00; Sound Around—Let’s Make Sound Rue Sésame—France, Catherine Smith and Helen Roussel Maps, 10/9, 10:30, Ages 9-11; Sesame Park—Canada, www.sofo.org/naturewalks.asp Vila Sesamo—Brazil, for their service.