Effects of Sesame Street: a Meta-Analysis of Children's Learning in 15 Countries☆,☆☆

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sesame Street “Dalam Pengembangan Bahasa Inggris Anak Usia Dini

Jurnal Golden Age, Universitas Hamzanwadi Vol. 5 No. 02, Juni 2021, Hal. 185-195 E-ISSN : 2549-7367 https://doi.org/10.29408/jga.v5i01.3489 Analisis Film Serial Televisi “Sesame Street “Dalam Pengembangan Bahasa Inggris Anak Usia Dini Resti Marguri 1, Rismareni Pransiska 2 Universitas Negeri Padang 1, 2 Email : [email protected] , [email protected] Abstrak Tujuan dari penelitian ini yakni untuk menganalisis film serial televisi Sesame Street dalam pengembangan Bahasa Inggris anak usia dini. Pada penelitian ini peneliti memakai metode kualitatif dengan pendekatan deskriptif. Pada film ini yang akan dianalisis yaitu kosakata, artikulasi atau pelafalan kata, bahasa tubuh, dan ungkapan sederhana. Setiap serial film ini memiliki kosakata yang sangat beragam serta dapat menambah pembendaharaan bahasa anak, memiliki artikulasi atau pelafalan kata yang jelas karena diucapkan langsung oleh penutur asli Selanjutnya pada penyajian film ini bahasa tubuh yang ditampilkan pun sangat jelas dan sesuai dengan penempatan kata Bahasa Inggris yang dilontarkan pada subtitle sehingga anak lebih mudah memahami makna dari Bahasa Inggris film ini. analisis selanjutnya pada film ini yaitu ungkapan sederhana berbahasa Inggris yang ada didalam film ini juga sangat banyak ditemukan yang nantinya dapat anak pratekkan dalam berkomunikasi sehari-hari karena bahasanya lebih simple dan sederhana serta ungkapan sederhana sangat umum dipakai dalam komunikasi sehari- hari. Kata kunci : Film Serial Televisi Sesame Street, Bahasa Inggris, Anak Usia Dini Abstrack The purpose of this study was to analyze the television series Sesame Street in the development of early childhood English. In this study, researchers used a qualitative method with a descriptive approach. In this film what will be analyzed are vocabulary, word articulation or pronunciation, body language, and simple expressions. -

The Case of Sesame Workshop

IPMN Conference Paper USING COMPLEX SUPPLY THEORY TO CREATE SUSTAINABLE PUBLIC-PRIVATE PARTNERSHIPS FOR SERVICE DELIVERY: THE CASE OF SESAME WORKSHOP Hillary Eason ABSTRACT This paper analyzes the potential uses of complex supply theory to create more finan- cially and institutionally sustainable partnerships in support of public-sector and non- profit service deliveries. It considers current work in the field of operations theory on optimizing supply chain efficiency by conceptualizing such chains as complex adaptive systems, and offers a theoretical framework that transposes these ideas to the public sector. This framework is then applied to two case studies of financially and organiza- tionally sustainable projects run by the nonprofit Sesame Workshop. This research is intended to contribute to the body of literature on the science of delivery by introducing the possibility of a new set of tools from the private sector that can aid practitioners in delivering services for as long as a project requires. Keywords - Complex Adaptive Systems, Partnership Management, Public-Private Part- nerships, Science of Delivery, Sustainability INTRODUCTION Financial and organizational sustainability is a major issue for development projects across sectors. Regardless of the quality or impact of an initiative, the heavy reliance of most programs on donor funding means that their existence is contingent on a variety of external factors – not least of which is the whims and desires of those providing finan- cial support. The rise of the nascent “science of delivery” provides us with an opportunity to critical- ly examine how such projects, once proven effective, can be sustainably implemented and supported over a long enough period to create permanent change. -

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 329 218 IR 014 857 TITLE Development Communication Report, 1990/1-4, Nos. INSTITUTION Agency for Internationa

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 329 218 IR 014 857 TITLE Development Communication Report, 1990/1-4, Nos. 68-71. INSTITUTION Agency for International Development (IDCA), Washington, DC. Clearinghouse on Development Communication. PUB DATE 90 NOTE 74p.; For the 1989 issues, see ED 319 394. AVAILABLE FROMClearinghouse on Development Communication, 1815 North Fort Meyers Dr., Suite 600, Arlington, VA 22209. PUB TYPE Collected Works - Serials (022) -- Reports - Descriptive (141) JOURNAL CIT Development Communication Report; n68-71 1990 EDRS PRICE MF01/PC03 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Adult Literacy; *Basic Skills; Change Strategies; Community Education; *Developing Nations; Development Communication; Educational Media; *Educational Technology; Educational Television; Feminism; Foreign Countries; *Health Education; *Literacy Education; Mass Media Role; Public Television; Sex Differences; Teaching Models; Television Commercials; *Womens Education ABSTRACT The four issues of this newsletter focus primarily on the use of communication technologies in developing nations tc educate their people. The first issue (No. 68) contains a review of the current status of adult literacy worldwide and articles on an adult literacy program in Nepal; adult new readers as authors; testing literacy materials; the use Jf hand-held electronic learning aids at the primary level in Belize; the use of public television to promote literacy in the United States; reading programs in Africa and Asia; and discussions of the Laubach and Freirean literacy models. Articles in the second issue (no. 69) discuss the potential of educational technology for improving education; new educational partnerships for providing basin education; gender differences in basic education; a social marketing campaign and guidelines for the improvement of basic education; adaptations of educational television's "Sesame Street" for use in other languages and cultures; and resources on basic education. -

Sesame Street Combining Education and Entertainment to Bring Early Childhood Education to Children Around the World

SESAME STREET COMBINING EDUCATION AND ENTERTAINMENT TO BRING EARLY CHILDHOOD EDUCATION TO CHILDREN AROUND THE WORLD Christina Kwauk, Daniela Petrova, and Jenny Perlman Robinson SESAME STREET COMBINING EDUCATION AND ENTERTAINMENT TO Sincere gratitude and appreciation to Priyanka Varma, research assistant, who has been instrumental BRING EARLY CHILDHOOD in the production of the Sesame Street case study. EDUCATION TO CHILDREN We are also thankful to a wide-range of colleagues who generously shared their knowledge and AROUND THE WORLD feedback on the Sesame Street case study, including: Sashwati Banerjee, Jorge Baxter, Ellen Buchwalter, Charlotte Cole, Nada Elattar, June Lee, Shari Rosenfeld, Stephen Sobhani, Anita Stewart, and Rosemarie Truglio. Lastly, we would like to extend a special thank you to the following: our copy-editor, Alfred Imhoff, our designer, blossoming.it, and our colleagues, Kathryn Norris and Jennifer Tyre. The Brookings Institution is a nonprofit organization devoted to independent research and policy solutions. Its mission is to conduct high-quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. The conclusions and recommendations of any Brookings publication are solely those of its author(s) and do not reflect the views of the Institution, its management, or its other scholars. Support for this publication and research effort was generously provided by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation and The MasterCard Foundation. The authors also wish to acknowledge the broader programmatic support of the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, the LEGO Foundation, and the Government of Norway. Brookings recognizes that the value it provides is in its absolute commitment to quality, independence, and impact. -

Egypt Education Legacy 35 Years of a Partnership in Education

EGYPT EDUCATION LEGACY 35 YEARS OF A PARTNERSHIP IN EDUCATION January 2012 This report was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development, Mission to Egypt (USAID/Egypt), under a task order of the Global Evaluation and Monitoring (GEM II) IQC, Contract No. EDH-E-23-08- 00003-00. It was prepared by the Aguirre Division of JBS International, Inc. Cover page photo by GILO project EGYPT EDUCATION LEGACY January 2012 The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. This document is available in printed and online versions. The online version is stored at the Development Experience Clearinghouse (http://dec.usaid.gov). Additional information can be obtained from [email protected]. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) would like to express sincere gratitude to the many institutions and people who have made the 35-year partnership in Egypt’s education sector so fruitful. The education system has benefited from the valuable collaboration of many Egyptian officials and policy makers. First, we would like to express our sincere gratitude to the Government of Egypt, primarily the Ministry of Education. Several officials have led this office over the years, and we acknowledge each and every one of them. We are also grateful to staff in departments and units at the central, governorate (Muddiraya), district (Idara), and school levels. Success in the sector is due largely to the support and sincere cooperation of all these key actors. USAID would especially like to thank Dr. -

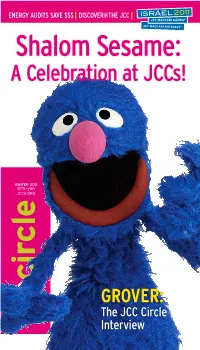

Shalom Sesame: a Celebration at Jccs!

energy audits save $$$ | discover@the jcc | shalom sesame: a celebration at JCCs! winter 2011 5771 qruj jcca.org circle Grover: the JCC circle interview insidewinter 2011 5771 qruj www.jcca.org Encouraging Jewish engagement 2 Allan Finkelstein DISCOVER @ THE JCC 4 Transcending fitness Viva Tel Aviv! 10 The other city that never sleeps Israel 2011: A dream come true 14 JCC Maccabi Games and ArtsFest in Eretz Yisrael Five secrets to building a great 18 board-executive relationship With Gary LIpman Nashville Journal: 20 Floodwaters, Gordon JCC rise to the occasion It’s money in the bank 22 Why you ought to have an energy audit now Grover: A world-traveler visits Israel 26 The JCC Circle interview Shalom Sesame and engaging families 28 The premiere is just the beginning Securing professional talent 32 Who will lead your JCC in ten years? For address correction or information about JCC Circle contact [email protected] or call (212) 532-4949. ©2010 jewish community centers association of north america. all rights reserved. 520 eighth avenue | new York, nY 10018 Phone: 212-532-4949 | Fax: 212-481-4174 | e-mail: [email protected] | web: www.jcca.org JCC association of north america is the leadership network of, and central agency for, 350 jewish community centers, YM-YwHas and camps in the United States and canada, that annually serve more than two million users. JCC association offers a wide range of services and resources to enable its affiliates to provide educational, cultural and recreational programs to enhance the lives of north american jewry. JCC association is also a U.S. -

Sanibona Bangane! South Africa

2003 ANNUAL REPORT sanibona bangane! south africa Takalani Sesame Meet Kami, the vibrant HIV-positive Muppet from the South African coproduction of Sesame Street. Takalani Sesame on television, radio and through community outreach promotes school readiness for all South African children, helping them develop basic literacy and numeracy skills and learn important life lessons. bangladesh 2005 Sesame Street in Bangladesh This widely anticipated adaptation of Sesame Street will provide access to educational opportunity for all Bangladeshi children and build the capacity to develop and sustain quality educational programming for generations to come. china 1998 Zhima Jie Meet Hu Hu Zhu, the ageless, opera-loving pig who, along with the rest of the cast of the Chinese coproduction of Sesame Street, educates and delights the world’s largest population of preschoolers. japan 2004 Sesame Street in Japan Japanese children and families have long benefited from the American version of Sesame Street, but starting next year, an entirely original coproduction designed and produced in Japan will address the specific needs of Japanese children within the context of that country’s unique culture. palestine 2003 Hikayat Simsim (Sesame Stories) Meet Haneen, the generous and bubbly Muppet who, like her counterparts in Israel and Jordan, is helping Palestinian children learn about themselves and others as a bridge to cross-cultural respect and understanding in the Middle East. egypt 2000 Alam Simsim Meet Khokha, a four-year-old female Muppet with a passion for learning. Khokha and her friends on this uniquely Egyptian adaptation of Sesame Street for television and through educational outreach are helping prepare children for school, with an emphasis on educating girls in a nation with low literacy rates among women. -

Principal's Corner

ORLANDO SCIENCE SCHOOLS WEEKLY NEWSLETTER The mission of the Orlando Science Schools (OSS) is to use proven and innovative instructional methods and exemplary reform-based curricula in a stimulating environment with the result of providing its Date: 11/09/2012 students a well-rounded middle school and high school education in all subject areas. OSS will provide rigorous college preparatory programs with a special emphasis in mathematics, science, technology, Issue 116 and language arts. Principal’s Corner Dear Students & Parents, Yet another great week at OSS! Individual Highlights Please check out page 2 to read about our can tab collection to help Principal’s Corner 1 those in need at the Ronald McDonald House and OSS’ PVO meeting! Can Tabs 2 Check out page 3 for upcoming and past events and OSS got into the OSS PVO meeting 2 spirit of the nation and held their own mock election, so “poll” your Upcoming Events 3 way to page 4 for more info and while you’re there scroll on down to Week in History 3 page 5 to applaud OSS’ Characters of the Month! OSS Mock Election 4 As OSS and OSES grows, we need help from our parents to make our OSS Character of the Month 5 outside area more conducive for our student activities. Please read page 6 for more information. Check our yummy lunch menu on 7, Playground Donations 6 “Read” about our book fair on page 8 with a reminder about the Menus 7 winter dress code and a coupon! This Thanksgiving is an opportunity to help those in need so “gobble’ on down to page 9 to All Star Book Fair 8 learn more. -

Humor and Translation Mark Herman Mt

Herman is a librettist and translator. Submit items for future columns via e-mail to [email protected] or via snail mail to Mark Herman, 1409 E Gaylord Street, Humor and Translation Mark Herman Mt. Pleasant, MI 48858-3626. Discussions of the hermanapter@ translation of humor and examples thereof are preferred, cmsinter.net but humorous anecdotes about translators, translations, and mistranslations are also welcome. Include copyright Sesame Street information and permission if relevant. This column is based on various and a plummeting birthrate, it would among that nation’s considerable Internet postings, including those of be difficult. Obedience, solemnity, and Muslim population. The New York Times and the BBC. duty seemed to be all that Russian chil- Charlotte Beers, Undersecretary of In July 1969, test episodes of the dren knew. Children who were asked State for Public Diplomacy, warned a children’s program Sesame Street to audition for the show largely sat Senate committee that the “people we were seen on a Philadelphia educa- back in their chairs and sang sad songs. need to talk to do not even know the tional station. The first nationally tel- And, before they could cheer up tod- basics about us. They are taught to evised episode ran in November of dlers, the producers had to cheer up the distrust our every motive. Such dis- that year. Vila Sesamo aired in Brazil writers, some of whom wanted to use tortions, married to a lack of knowl- in 1972; Sesamstrasse in Germany in the word ltghtccbz (depression) to edge, is a deadly cocktail. Engaging 1973; 1, rue Sesame in France in teach children how to use the letter and teaching common values are pre- 1978; Улuцa Ceзaм in Russia in L (D). -

Galli Galli Sim Sim’ Reintroduced in Kashmir

Vol 11No 10Pages 08JULY 30 2018 ﻮر य ﯽ اﻟﻨ गम ﻟ ोत ﺖ ا ﻤ ٰ ा ﻠ ﻈ म ﻟ ो ا ﻦ स ﻣ म त U N IR IV M ER H MERC TIMESSITY OF KAS MEDIA EDUCATION RESEARCH CENTRE UNIVERSITY OF KASHMIR Edutainment show ‘Galli Galli Sim Sim’ reintroduced in Kashmir 16 years on , Anantnag shopping 2 years on Disablities Act Bill, yet 4 years on; Rohmu residents await INSIDE {STORIES} complex yet to complete to be passed in kashmir completion of the bridge P 03 P 06 P 07 ﻮر य ﯽ اﻟﻨ गम ﻟ ोत ﺖ ا ﻤ ٰ ा ﻠ MEDIA EDUCATION RESEARCH CENTRE, UNIVERSITY OF KASHMIR ﻈ म ﻟ ो ا ﻦ स ﻣ म त U N IR IV M ER H SITY OF KAS Vol 11 | No 10 | JULY 30, 2018 02 Edutainment show ‘Galli Galli Sim Sim’ reintroduced in Kashmir Tahil Ali to whom these shows are directed.” Anantnag “Apart from learning about general ethics and morals, children of Kashmir upported by Vitol Foundation, in particular, will also be creatively given Such programs are Doordarshan (DD) Kashir and DD exposure to cultural nuances, skill building, SUrdu, edutainment show ‘Galli Galli and value of emotions,” said Malik Zahra. culturally relevant to Sim Sim’ makes a comeback to Kashmir. “Galli Galli Sim Sim” is a flagship initiative The Indian adaptation of Sesame Street will in which special programs have been the native population of be broadcast in Kashmiri and Urdu on DD produced covering important themes about Kashir from Monday to Sunday at 6:30 PM school going children. -

Nurturing Creativity in Children: a Jalan Sesama Initiative

Nurturing MuhammadCreativity Zuhdi in Children: Director of Education, Research and Outreach A Jalan Sesama Initiative Muhammad Zuhdi Director of Education, Research and Outreach Jalan Sesama Presented at 15th UNESCO-APEID International Conference “Inspiring Education: Creativity and Entrepreneurship” Jakarta, 6 – 8 December 2011 What is Jalan Sesama? • An educational initiative that utilizes the strengths of media to deliver educational messages to Indonesian children. • The Indonesian version of SESAME STREET • Co-production: Sesame Workshop (New York) and PT. Creative Indigo Production (Jakarta) • Programs: – TV Show (Trans7: 2008 – 2010, Kompas TV: 2011 - ... ) – Magazine (Gramedia) – Outreach Programs (West Jawa, West Nusa Tenggara, Papua: 2011 – 2012) targetting ECED (PAUD) • Funded by USAID Mission Use television and other media to help Indonesian children ages 3 to 6 learn basic skills that help them prepared for entry into primary school. Main Characters PUTRI MOMON JABRIK TANTAN The Sesame Workshop Model Sesame Workshop co-productions are always designed to consistently entertain and educate. An innovative approach which applies and at the same time combines various skills in the production field, mastery of children’s educational material, and research. Proven to be effective and has influenced children’s lives all over the world for more than 40 years. Jalan Sesama & Creativity In Season 5 of its TV Show, Jalan Sesama addresses creativity as the theme. Why Creativity? • Skill necessary for children • Important, but often -

Big Dreams Sparked by a Spirited Girl Muppet

GLOBAL GIRLS’ EDUCATION Big Dreams Sparked by a Spirited Girl Muppet Globally, an estimated 510 million women grow up unable to read and write – nearly twice the rate of adult illiteracy as men.1 To counter this disparity in countries around the world, there’s Sesame Street. Local adaptations of Sesame Street are opening minds and doors for eager young learners, encouraging girls to dream big and gain the skills they need to succeed in school and life. We know these educational efforts yield benefits far beyond girls’ prospects. They produce a ripple effect that advances entire families and communities. Increased economic productivity, reduced poverty, and lowered infant mortality rates are just a few of the powerful outcomes of educating girls. “ Maybe I’ll be a police officer… maybe a journalist… maybe an astronaut!” Our approach is at work in India, Bangladesh, Nigeria, Egypt, South Africa, Afghanistan, and many other developing countries where educational and professional opportunities for women are limited. — Khokha Afghanistan BAGHCH-E-SIMSIM Bangladesh SISIMPUR Brazil VILA SÉSAMO China BIG BIRD LOOKS AT THE WORLD Colombia PLAZA SÉSAMO Egypt ALAM SIMSIM India GALLI GALLI SIM SIM United States Indonesia JALAN SESAMA Israel RECHOV SUMSUM Mexico PLAZA SÉSAMO Nigeria SESAME SQUARE Northern Ireland SESAME TREE West Bank / Gaza SHARA’A SIMSIM South Africa TAKALANI SESAME Tanzania KILIMANI SESAME GLOBAL GIRLS’ EDUCATION loves about school: having lunch with friends, Watched by millions of children across the Our Approach playing sports, and, of course, learning new country, Baghch-e-Simsim shows real-life girls things every day. in situations that have the power to change Around the world, local versions of Sesame gender attitudes.