Iran Sanctions and Regional Security Hearing Committee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iran Case File (April 2021)

IRAN CASE FILE April 2021 RASANAH International Institute for Iranian Studies, Al-Takhassusi St. Sahafah, Riyadh Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. P.O. Box: 12275 | Zip code: 11473 Contact us [email protected] +966112166696 Executive Summary .....................................................................................4 Internal Affairs ........................................................................................... 7 The Ideological File .............................................................................................8 1. Women and the “Political Man” ............................................................................... 8 2. Khatami and the Position of Women ......................................................................10 The Political File ............................................................................................... 12 1. The Most Notable Highlights of the Leaked Interview .............................................12 2. Consequences and Reactions .................................................................................13 3. The Position of the Iranian President and Foreign Ministry on the Interview ..........14 4. The Implications of Leaking the Interview at This Time..........................................15 The Economic File ............................................................................................. 16 1. Bitcoin’s Genesis Globally and the Start of Its Use in Iran ........................................16 2. The Importance of Bitcoin for Iran -

The 'New Middle East,' Revised Edition

9/29/2014 Diplomatist BILATERAL NEWS: India and Brazil sign 3 agreements during Prime Minister's visit to Brazil CONTENTS PRINT VERSION SPECIAL REPORTS SUPPLEMENTS OUR PATRONS MEDIA SCRAPBOOK Home / September 2014 The ‘New Middle East,’ Revised Edition GLOBAL CENTRE STAGE In July 2014, President Obama sent the White House’s Coordinator for the Middle East, Philip Gordon, to address the ‘Israel Conference on Peace’ in Tel-Aviv. ‘How’ Gordon asked ‘will [Israel] have peace if it is unwilling to delineate a border, end the occupation and allow for Palestinian sovereignty, security, and dignity?’ This is a good question, but Dr Emmanuel Navon asks how Israel will achieve peace if it is willing to delineate a border, end the occupation and allow for Palestinian sovereignty, security, and dignity, especially when experience, logic and deduction suggest that the West Bank would turn into a larger and more lethal version of the Gaza Strip after the Israeli withdrawal During the last war between Israel and Hamas (which officially ended with a ceasefire on August 27, 2014), US Secretary of State John Kerry inadvertently created a common ground among rivals: Israel, the Palestinian Authority, Egypt and Jordan all agreed in July 2014 that Kerry had ruined the chances of a ceasefire between Israel and Hamas. Collaborating with Turkey DEFINITION and Qatar to reach a ceasefire was tantamount to calling the neighbourhood’s pyromaniac instead of the fire department to extinguish the fire. Qatar bankrolls Hamas and Turkey advocates on its behalf. While in Paris in July, Kerry was all smiles Diplomat + with Turkish Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoglu whose boss, Recep Erdogan, recently accused Israel of genocide and compared Netanyahu to Hitler. -

O'hanlon Gordon Indyk

Getting Serious About Iraq 1 Getting Serious About Iraq ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ Philip H. Gordon, Martin Indyk and Michael E. O’Hanlon In his 29 January 2002 State of the Union address, US President George W. Bush put the world on notice that the United States would ‘not stand aside as the world’s most dangerous regimes develop the world’s most dangerous weapons’.1 Such statements, repeated since then in various forms by the president and some of his top advisers, have rightly been interpreted as a sign of the administration’s determination to overthrow Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein.2 Since the January declaration, however, attempts by the administration to put together a precise plan for Saddam’s overthrow have revealed what experience from previous administrations should have made obvious from the outset: overthrowing Saddam is easier said than done. Bush’s desire to get rid of the Iraqi dictator has so far been frustrated by the inherent difficulties of overthrowing an entrenched regime as well as a series of practical hurdles that conviction alone cannot overcome. The latter include the difficulties of organising the Iraqi opposition, resistance from Arab and European allies, joint chiefs’ concerns about the problems of over-stretched armed forces and intelligence assets and the complications caused by an upsurge in Israeli– Palestinian violence. Certainly, the United States has good reasons to want to get rid of Saddam Hussein. Saddam is a menace who has ordered the invasion of several of his neighbours, killed thousands of Kurds and Iranians with poison gas, turned his own country into a brutal police state and demonstrated an insatiable appetite for weapons of mass destruction. -

Evaluation of Heavy Metals Concentration in Jajarm Bauxite Deposit in Northeast of Iran Using Environmental Pollution Indices

Malaysian Journal of Geosciences (MJG) 3(1) (2019) 12-20 Malaysian Journal of Geosciences (MJG) DOI : http://doi.org/10.26480/mjg.01.2019.12.20 ISSN: 2521-0920 (Print) ISSN: 2521-0602 (Online) CODEN: MJGAAN REVIEW ARTICLE EVALUATION OF HEAVY METALS CONCENTRATION IN JAJARM BAUXITE DEPOSIT IN NORTHEAST OF IRAN USING ENVIRONMENTAL POLLUTION INDICES Ali Rezaei1*, Hossein Hassani1, Seyedeh Belgheys Fard Mousavi2, Nima Jabbari3 1Department of Mining and Metallurgy Engineering, Amirkabir University of Technology, Tehran, Iran 2Department of Agriculture and Environmental Engineering, Tehran University, Tehran, Iran 3Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Southern California, USA *Corresponding Author E-mail: [email protected] , [email protected] This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. ARTICLE DETAILS ABSTRACT Article History: Heavy metals are known as an important group of pollutants in soil. Major sources of heavy metals are modern industries such as mining. In this study, spatial distribution and environmental behavior of heavy metals in the Jajarm Received 20 November 2018 bauxite mine have been investigated. The study area is one of the most important deposits in Iran, which includes about Accepted 21 December 2018 22 million tons of reserve. Contamination factor (CF), the average concentration (AV), the enrichment factor (EF) and Available online 4 January 2019 geoaccumulation index (GI) were factors used to assess the risk of pollution from heavy metals in the study area. Robust principal component analysis of compositional data (RPCA) was also applied as a multivariate method to find the relationship among metals. -

America's Anxious Allies: Trip Report from Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and Israel by Meghan O'sullivan, Philip Gordon, Dennis Ross, James Jeffrey

MENU Policy Analysis / PolicyWatch 2696 America's Anxious Allies: Trip Report from Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and Israel by Meghan O'Sullivan, Philip Gordon, Dennis Ross, James Jeffrey Sep 28, 2016 Also available in Arabic ABOUT THE AUTHORS Meghan O'Sullivan Meghan O'Sullivan is the Jeane Kirkpatrick Professor of the Practice of International Affairs at Harvard University's Kennedy School. Philip Gordon Philip Gordon is a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations and a former White House coordinator for the Middle East, North Africa, and the Gulf region. Dennis Ross Dennis Ross, a former special assistant to President Barack Obama, is the counselor and William Davidson Distinguished Fellow at The Washington Institute. James Jeffrey Ambassador is a former U.S. special representative for Syria engagement and former U.S. ambassador to Turkey and Iraq; from 2013-2018 he was the Philip Solondz Distinguished Fellow at The Washington Institute. He currently chairs the Wilson Center’s Middle East Program. Brief Analysis A bipartisan team of distinguished former officials share their insights from a recent tour of key regional capitals. On September 26, The Washington Institute held a Policy Forum with Meghan O'Sullivan, Philip Gordon, Dennis Ross, and James Jeffrey, who recently returned from a bipartisan tour of Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and Israel. O'Sullivan is the Jeane Kirkpatrick Professor at Harvard's Kennedy School and former special assistant to the president for Iraq and Afghanistan. Gordon is a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations and former White House coordinator for the Middle East, North Africa, and the Gulf region. -

Seeking Stability at Sustainable Cost: Principles for a New U.S

Seeking Stability at Sustainable Cost: Principles for a New U.S. Strategy in the Middle East Report of the Task Force on Managing Disorder in the Middle East April 2017 Aaron Lobel Task Force Co-Chairs Founder and President, America Abroad Media Ambassador Eric Edelman Former U.S. Ambassador to Turkey Mary Beth Long Former Assistant Secretary of Defense for International Security Jake Sullivan Affairs Former Director of Policy Planning, U.S. State Department Former National Security Advisor to the Vice President Alan Makovsky Former Senior Professional Staff Member, House Foreign Affairs Committee Task Force Members Ray Takeyh Ambassador Morton Abramowitz Former Senior Advisor on Iran, U.S. State Department Former U.S. Ambassador to Turkey General Charles Wald (ret., USAF) Henri Barkey Former Deputy Commander, U.S. European Command Director, Middle East Program, Woodrow Wilson International Center Former Commander, U.S. Central Command Air Forces Hal Brands Amberin Zaman Henry A. Kissinger Distinguished Professor of Global Affairs at the Columnist, Al-Monitor; Woodrow Wilson Center Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies Svante Cornell Staff Director, Central Asia-Caucasus Institute and Silk Road Studies Program Blaise Misztal Director of National Security Ambassador Ryan Crocker Former U.S. Ambassador to Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon Nicholas Danforth Senior Policy Analyst Ambassador Robert Ford Former Ambassador to Syria Jessica Michek Policy Analyst John Hannah Former Assistant for National Security Affairs to the Vice President Ambassador James Jeffrey Former Ambassador to Turkey and Iraq DISCLAIMER The findings and recommendations expressed herein do not necessarily represent the views or opinions of the Bipartisan Policy Center’s founders or its board of directors. -

Focus on Mining in Iran

FOCUS ON MINING IN IRAN 27 November 2015 | Iran Group Legal Briefings – By Andrew Cannon, Partner, Paris, Adam McWilliams, Senior Associate, London and Naomi Lisney, Associate, Paris. IN BRIEF Iran is among the world's top 10 most resource-rich countries. While primarily known for its hydrocarbons, the country is also home to some 68 minerals together reportedly worth $700 billion, with more than 37bnt (billion tonnes) of proven reserves and 57bnt of potential reserves, which include considerable deposits in coal, iron ore, copper, lead, zinc, chromium, barite, uranium and gold. The Sarcheshmeh mine in Iran holds the second's largest copper deposits in Asia, accounting for 25.3% of Asian reserves and around 6% of global reserves. SUMMARY Mining currently only plays a minor role in the Iranian economy; however, the Iranian leadership is actively seeking to promote growth in its mining sector to reduce its dependency on oil. According to the Iranian Mines and Mining Industries Development & Renovation Organization (IMIDRO), it has, through subsidiary companies, invested more than $10 billion in upstream and downstream mining projects since its establishment in 2001, and currently has $9 billion invested in 29 projects, including steel, aluminium, rare earth elements, copper and gold mines. At the Iran-EU Conference on Trade & Investment, held on 23-24 July 2015 in Vienna, Austria, Mehdi Karbasian, Deputy Minister and Chairman of IMIDRO, said Iran will require a further $20 billion in investment for its mining sector by 2025. He invited foreign and private sector investment, introducing the incentives already introduced in Iran, and expressing IMIDRO's support for foreign investment. -

The US Perspective on NATO Under Trump: Lessons of the Past and Prospects for the Future

The US perspective on NATO under Trump: lessons of the past and prospects for the future JOYCE P. KAUFMAN Setting the stage With a new and unpredictable administration taking the reins of power in Wash- ington, the United States’ future relationship with its European allies is unclear. The European allies are understandably concerned about what the change in the presidency will mean for the US relationship with NATO and the security guar- antees that have been in place for almost 70 years. These concerns are not without foundation, given some of the statements Trump made about NATO during the presidential campaign—and his description of NATO on 15 January 2017, just days before his inauguration, as ‘obsolete’. That comment, made in a joint interview with The Times of London and the German newspaper Bild, further exacerbated tensions between the United States and its closest European allies, although Trump did claim that the alliance is ‘very important to me’.1 The claim that it is obsolete rested on Trump’s incorrect assumption that the alliance has not been engaged in the fight against terrorism, a position belied by NATO’s support of the US conflict in Afghanistan. Among the most striking observations about Trump’s statements on NATO is that they are contradicted by comments made in confirmation hear- ings before the Senate by General James N. Mattis (retired), recently confirmed as Secretary of Defense, who described the alliance as ‘essential for Americans’ secu- rity’, and by Rex Tillerson, now the Secretary of State.2 It is important to note that the concerns about the future relationships between the United States and its NATO allies are not confined to European governments and policy analysts. -

Phosphate Occurrence and Potential in the Region of Afghanistan, Including Parts of China, Iran, Pakistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan

Phosphate Occurrence and Potential in the Region of Afghanistan, Including Parts of China, Iran, Pakistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan By G.J. Orris, Pamela Dunlap, and John C. Wallis With a section on geophysics by Jeff Wynn Open-File Report 2015–1121 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior SALLY JEWELL, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Suzette M. Kimball, Acting Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2015 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod To order this and other USGS information products, visit http://store.usgs.gov Suggested citation: Orris, G.J., Dunlap, Pamela, and Wallis, J.C., 2015, Phosphate occurrence and potential in the region of Afghanistan, including parts of China, Iran, Pakistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan, with a section on geophysics by Jeff Wynn: U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2015-1121, 70 p., http://dx.doi.org/10.3133/ofr20151121. Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted material contained within this report. Contents -

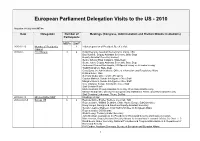

The Information Below Is Based on the Information Supplied to EPLO and Stored in Its Archives and May Differ from the Fina

European Parliament Delegation Visits to the US - 2010 Situation: 01 July 2010 MT/mt Date Delegation Number of Meetings (Congress, Administration and Bretton-Woods Institutions) Participants MEPs Staff* 2010-02-16 Member of President's 1 Initial preparation of President Buzek´s Visit Cabinet 2010-02- ECR Bureau 9 4 David Heyman, Assistant Secretary for Policy, TSA Dan Russell, Deputy Assistant Secretary ,State Dept Deputy Assistant Secretary Limbert, Senior Advisor Elisa Catalano, State Dept Stuart Jones, Deputy Assistant Secretary, State Dept Ambassor Richard Morningstar, US Special Envoy on Eurasian Energy Todd Holmstrom, State Dept Cass Sunstein, Administrator, Office of Information and Regulatory Affiars Kristina Kvien, NSC Sumona Guha, Office of Vice-President Gordon Matlock, Senate Intelligence Cttee Staff Margaret Evans, Senate Intelligence Cttee Staff Clee Johnson, Senate Intelligence Cttee Staff Staff Senator Risch Mark Koumans, Deputy Assistant Secretary, Dept Homeland Security Michael Scardeville, Director for European and Multilateral Affairs, Dept Homeland Security Staff Senators Lieberman, Thune, DeMint 2010-02-18 Mrs Lochbihler MEP 1 Meetings on Iran 2010-03-03-5 Bureau US 6 2 Representative Shelley Berkley, Co-Chair, TLD Representative William Delahunt, Chair, House Europe SubCommittee Doug Hengel, Energy and Sanctions Deputy Assistant Secretary Senator Jeanne Shaheen, Chair Subcommittee on European Affairs Representative Cliff Stearns Stuart Levey, Treasury Under Secretary John Brennan, Assistant to the President for -

FALL COMMENCEMENT 2020 CELEBRATING the GRADUATING CLASS So Enter That Daily Thou Mayest Grow in Knowledge Wisdom and Love

FALL COMMENCEMENT 2020 CELEBRATING THE GRADUATING CLASS So enter that daily thou mayest grow in knowledge wisdom and love. To the Class of 2020, Congratulations on your graduation from Ohio University! You are one of the fortunate who has experienced the nation’s best transformative learning experience. This year has not been what any of us had planned, as the COVID-19 global pandemic changed all of our lives. I want to thank you for boldly responding to these historic changes by continuing to learn together, work together and support one another. You have shown great resilience as you navigated the many challenges of 2020 and I am very proud of you. Your class is truly special and will always be remembered at Ohio University for your spirit and fortitude. Your time at Ohio University prepared you for your future, and now you and your classmates are beginning your careers, advancing in new academic programs or taking on other challenges. I want you to know, though, that your transformation is not yet complete. For a true education does not stop with a diploma; it continues throughout every day of your life. I encourage you to take the lessons you have learned at Ohio University and expand upon them in the years to come. As you have already learned, the OHIO alumni network is a vast enterprise – accomplished in their respectable professions, loyal to their alma mater, and always willing to help a fellow Bobcat land that next job or find an apartment/realtor in a new city. I urge you to seek out your nearest alumni chapter or a special interest society of alumni and friends, to reach out through social media (#ohioalumni), and to stay connected to Ohio University. -

An Archaeometrical Analysis of the Column Bases from Hegmatâneh to Ascertain Their Source of Provenance

Volume III ● Issue 2/2012 ● Pages 221–227 INTERDISCIPLINARIA ARCHAEOLOGICA NATURAL SCIENCES IN ARCHAEOLOGY homepage: http://www.iansa.eu III/2/2012 An Archaeometrical Analysis of the Column Bases from Hegmatâneh to Ascertain their Source of Provenance Masoud Rashidi Nejada*, Farang Khademi Nadooshana, Mostafa Khazaiea, Paresto Masjedia aDepartment of Archaeology at Tarbiat Modares University, 14115-139 Tehran, Iran ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: As a political and social statement, the style of the Achaemenid architecture was predicated on gran- Received: 15 April 2012 diose buildings and masonry, with the column as one of its primary elements. Often, the trunk of the Accepted: 15 November 2012 columns was made of either wood or stone, although their bases were always made of stone; a practice unique to ancient Iran. Consequently, access to stone for building these columns was of major impor- Key words: tance This paper deals with the sources used in the making of the column bases of Hegmatâneh follow- Achaemenid ing non-destructive techniques of petrography and XRD (X-ray Diffraction Spectrometry) analysis in Hamadan conjunction with geological data. In order to study them, we collected six samples from Hamadan and Hegmatâneh nine from column bases. Historical texts and geological formations were also taken into consideration. Petrography This study attempts to demonstrate the relationship between archaeological and environmental data by XRD statistical analysis, to be used as a tool for the identification of mineral resources in the future. 1. Introduction BC) (Grayson 1975, 106, 56). According to the Greek sources, Cyrus invaded Media because he wanted a political Petrography and XRD are two methods for the recognition independence (Brosius 2006, 8).