The Sponsorship Collaboration – a Game on Equal Terms?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Svff:S Tävlingsbestämmelser År 2013

SvFF:s Tävlingsbestämmelser år 2013 Begrepp 7 1 kap – Allmänna bestämmelser 1 § Tävlings- och spelregler 10 2 § Matchtillstånd 11 3 § Mästerskapstävlingar mm. 12 4 § IdrottsAB 12 5 § Deltagande i landskamper mm. 12 6 § Särskilda TB för Allsv. och Superettan 13 7 § Särskilda TB för Damallsvenskan 13 8 § Spelaragent 13 9 § Matchagent 14 10 § Arenakrav 14 10.1 Div. 1, herrar 10.2 Arenakrav fr.o.m. 2014 11 § Representationsbestämmelser 14 12 § Reglemente för Elitlicensen 14 13 § Deltagande i internationella klubbtävlingar 14 14 § Tillstånd för radio- eller TV-sändning 15 15 § Spelares medverkan i reklam 15 16 § Registrering av förenings- och personuppgifter 15 17 § Klassificering av matcher 16 18 § Träningsmatcher 16 2 kap - Administration Tävlingens genomförande 1 § Poängberäkning 17 2 § Placering i tävling 17 3 § Speltid 17 4 § Ersättare och avbytare 18 5 § Priser 19 6 § Seriesammansättning - serier 19 7 § Övriga distriktstävlingar 20 8 § Föreningars eget arr. av tävling/träningsmatch 20 1 8.1 Allmänt 8.2 Förutsättningar för nationella tillstånd 8.3 Internationella tävlingar och träningsmatcher 8.4 Internationell landskamp eller landslagsturnering i Sverige 9 § Anmälan till tävling 24 10 § Behörighet att anmäla lag till tävling 24 10.1 Allmänt 10.2 Kombinerade lag 10.3 Representationslag 11 § Anmälan av lag tillhörande nya föreningar 25 12 § Spelordning 25 13 § Matchändring 26 14 § Uppskjuten eller avbruten match 27 14.1 Uppskjuten/avbruten match pga. väderförhållanden mm. 14.2 Avbruten match pga. ordningsstörning 14.3 Match som återupptas 15 § Ordningsstörning – avbruten match 30 15.1 Tävling enligt seriemetoden 15.2 Tävling enligt utslagsmetoden 16 § Omspel av färdigspelad match 31 17 § Förening som utgår ur tävling/lämnar walk-over 31 18 § Ospelad match 32 19 § Upp- och nedflyttning 33 20 § Kval 35 20.1 Kvalordning avseende förbundsserierna 20.2 Kvalmetod i kval till div. -

Sportification and Transforming of Gender Boundaries in Emerging Swedish Women’S Football, 1966-1999

Equalize it!: Sportification and Transforming of Gender Boundaries in Emerging Swedish Women’s Football, 1966-1999 Downloaded from: https://research.chalmers.se, 2021-09-30 11:41 UTC Citation for the original published paper (version of record): Svensson, D., Oppenheim, F. (2018) Equalize it!: Sportification and Transforming of Gender Boundaries in Emerging Swedish Women’s Football, 1966-1999 The International journal of the history of sport, 35(6): 575-590 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09523367.2018.1543273 N.B. When citing this work, cite the original published paper. research.chalmers.se offers the possibility of retrieving research publications produced at Chalmers University of Technology. It covers all kind of research output: articles, dissertations, conference papers, reports etc. since 2004. research.chalmers.se is administrated and maintained by Chalmers Library (article starts on next page) The International Journal of the History of Sport ISSN: 0952-3367 (Print) 1743-9035 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fhsp20 Equalize It!: ‘Sportification’ and the Transformation of Gender Boundaries in Emerging Swedish Women’s Football, 1966–1999 Daniel Svensson & Florence Oppenheim To cite this article: Daniel Svensson & Florence Oppenheim (2019): Equalize It!: ‘Sportification’ and the Transformation of Gender Boundaries in Emerging Swedish Women’s Football, 1966–1999, The International Journal of the History of Sport, DOI: 10.1080/09523367.2018.1543273 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/09523367.2018.1543273 -

CSR in Swedish Football

CSR in Swedish football A multiple case study of four clubs in Allsvenskan By: Lina Nilsson 2018-10-09 Supervisors: Marcus Box, Lars Vigerland and Erik Borg Södertörn University | School of Social Sciences Master Thesis 30 Credits Business Administration | Spring term 2018 ABSTRACT The question of companies’ social responsibility taking, called Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), has been widely debated in research since the 1900s. However, the research connecting CSR to sport was not started until the beginning of the 2000s, meaning that there are still many gaps in sport research that has to be filled. One such gap is research on CSR in a Swedish football context. Accordingly, the purpose of the study was firstly to examine how and why Swedish football clubs – organised as non-profit associations or sports corporations – work with CSR, and secondly whether or not there was a difference in the CSR work of the two organisational forms. A multiple case study of four clubs in Allsvenskan was carried out, examining the CSR work – meaning the CSR concept and activities, the motives for engaging in CSR and the role of the stakeholders – in detail. In addition, the CSR actions of all clubs of Allsvenskan were briefly investigated. The findings of the study showed that the four clubs of the multiple case study had focused their CSR concepts in different directions and performed different activities. As a consequence, they had developed different competences and competitive advantages. Furthermore, the findings suggested that the motives for engaging in CSR were a social agenda, pressure from stakeholders and financial motives. -

Scandinavian Women's Football Goes Global – a Cross-National Study Of

Scandinavian women’s football goes global – A cross-national study of sport labour migration as challenge and opportunity for Nordic civil society Project relevance Women‟s football stands out as an important subject for sports studies as well as social sciences for various reasons. First of all women‟s football is an important social phenomenon that has seen steady growth in all Nordic countries.1 Historically, the Scandinavian countries have been pioneers for women‟s football, and today Scandinavia forms a centre for women‟s football globally.2 During the last decades an increasing number of female players from various countries have migrated to Scandinavian football clubs. Secondly the novel development of immigration into Scandinavian women‟s football is an intriguing example of the ways in which processes of globalization, professionalization and commercialization provide new challenges and opportunities for the Nordic civil society model of sports. According to this model sports are organised in local clubs, driven by volunteers, and built on ideals such as contributing to social cohesion in society.3 The question is now whether this civil society model is simply disappearing, or there are interesting lessons to be drawn from the ways in which local football clubs enter the global market, combine voluntarism and professionalism, idealism and commercialism and integrate new groups in the clubs? Thirdly, even if migrant players stay only temporarily in Scandinavian women‟s football clubs, their stay can create new challenges with regard to their integration into Nordic civil society. For participants, fans and politicians alike, sport appears to have an important role to play in the success or failure of the integration of migrant groups.4 Unsuccessful integration of foreign players can lead to xenophobic feelings, where the „foreigner‟ is seen as an intruder that pollutes the close social cohesion on a sports team or in a club. -

ERSÄTTNING Domare, Assisterande Domare Och Fjärdedomare Har Rätt Till Reseersättning

2021-01-29 FÖRESKRIFTER GÄLLANDE EKONOMISK ERSÄTTNING TILL DOMARE Förbundsserierna och övriga förbundstävlingar i fotboll Ersättning till domare, assisterande domare och fjärdedomare i förbundsserierna Allsvenskan–div. 3, herrar, Damallsvenskan–div. 1, damer, Svenska Cupen samt SEF U21-serier och ungdomsturneringar ska för spelåret 2021 utgå enligt nedan. MATCHARVODE Herrar Domare Assisterande domare Allsvenskan 9 170 kr 4 585 kr Superettan 4 895 kr 2 680 kr Ettan 2 490 kr 1 495 kr Div. 2 1 840 kr 1 100 kr Div. 3, SEF:s Folksam U21-serier, P19 Allsvenskan 1 390 kr 835kr P19 div 1, P17 Allsvenskan, Ligacupen P19 900 kr 655kr P17 div. 1, P16, Ligacupen P17 och P16 785 kr 575kr För fjärdedomare i Allsvenskan utgår arvode med 1 840 kr och i Superettan med 1 390 kr per match. Damer Damallsvenskan 2540 kr 1540 kr Elitettan Dam 1560 kr 905 kr Div. 1, damer 1130 kr 680 kr Svenska Spel F19 1130 kr 680 kr SM F17- slutspel (åttondelsfinaler, kvartsfinaler, semifinaler och final) 900 kr 655 kr SM F17-gruppspel 680 kr 495 kr För fjärdedomare i Damallsvenskan utgår arvode med 1 130 kr per match. Kvalspel Vid kvalspel utgår ersättning med ett belopp motsvarande det arvode som utgår i den serie som det laget med högst serietillhörighet tillhör. Svenska Cupen, herrar Ersättning utgår med belopp motsvarande det arvode som utgår i den serie som det lag med högst serietillhörighet tillhör, dock utgår ersättning som högst med ett belopp motsvarande match i Superettan. I semifinal och final utgår dock ersättning med ett belopp motsvarande match i Allsvenskan. -

Women's Football, Europe and Professionalization 1971-2011

Women’s Football, Europe and Professionalization 1971-2011 A Project Funded by the UEFA Research Grant Programme Jean Williams Senior Research Fellow International Centre for Sports History and Culture De Montfort University Contents: Women’s Football, Europe and Professionalization 1971- 2011 Contents Page i Abbreviations and Acronyms iii Introduction: Women’s Football and Europe 1 1.1 Post-war Europes 1 1.2 UEFA & European competitions 11 1.3 Conclusion 25 References 27 Chapter Two: Sources and Methods 36 2.1 Perceptions of a Global Game 36 2.2 Methods and Sources 43 References 47 Chapter Three: Micro, Meso, Macro Professionalism 50 3.1 Introduction 50 3.2 Micro Professionalism: Pioneering individuals 53 3.3 Meso Professionalism: Growing Internationalism 64 3.4 Macro Professionalism: Women's Champions League 70 3.5 Conclusion: From Germany 2011 to Canada 2015 81 References 86 i Conclusion 90 4.1 Conclusion 90 References 105 Recommendations 109 Appendix 1 Key Dates of European Union 112 Appendix 2 Key Dates for European football 116 Appendix 3 Summary A-Y by national association 122 Bibliography 158 ii Women’s Football, Europe and Professionalization 1971-2011 Abbreviations and Acronyms AFC Asian Football Confederation AIAW Association for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women ALFA Asian Ladies Football Association CAF Confédération Africaine de Football CFA People’s Republic of China Football Association China ’91 FIFA Women’s World Championship 1991 CONCACAF Confederation of North, Central American and Caribbean Association Football CONMEBOL -

Verksamhetsberättelse 2016 Verksamhetsberättelse 2016 IDROTTSFÖRENINGEN KAMRATERNA GÖTEBORG

VeRkSaMHETSbeRäTTeLSe 2016 VeRkSaMHETSbeRäTTeLSe 2016 IDROTTSFÖRENINGEN KAMRATERNA GÖTEBORG Ordinarie årsmöte, Burgården Konferens Måndagen den 6 mars 2017 kl 18:00 FÖREDRAGNINGSLISTA 1. Mötets öppnande – Inledningsanförande av och Mats Engström. klubbens ordförande. 15. Val av två revisorer för 2017. 2. Parentation. I tur att avgå: Jonas Jonasson och Jerry Carlsson. 3. Jörgen Lennartsson inför säsongen 2017. 16. Val av två revisorssuppleanter för 2017. 4. Prisutdelning och utdelning av utmärkelsetecken. I tur att avgå: Berth Hilmersson och Tommie Almgren. 5. a. Val av ordförande för mötet. 17. Val av tre ledamöter i Fondkommittén. b. Val av sekreterare för mötet. I tur att avgå: Jakob Andreasson, Ralph Öberg och Tage Christoffersson. 6. Fråga om mötets behöriga utlysande. 18. Val av tre ledamöter i Guldmedaljutskottet för 2017. 7. Godkännande av dagordningen. I tur att avgå: Kent Olsson, P-O Lundquist, Tore B 8. Val av justeringsmän att jämte ordförande justera Carlsson. årsmötets protokoll. 19. Val av tre ledamöter i Valberedningen inför årsmötet 9. Val av tre röstkontrollanter. 2018. 10. Godkännande av röstlängden. I tur att avgå: Joakim Brinkenberg, Marcus Toremar, 11. a. Föredragning av styrelsens verksamhets- Kent Olsson. respektive förvaltningsberättelse för 2016. 20. Behandling av till årsmötet inkomna förslag. b. Fondkommitténs berättelse för 2016. a. Uppföljning av vid tidigare årsmöte behandlade c. Genomgång av föreningens resultat- och motioner. balansräkning och revisionsberättelse. b. Styrelsens förslag beträffande sektionsstyrelser. 12. Fråga om ansvarsfrihet för styrelsen. c. Styrelsens förslag beträffande biljetter/biljett- priser. 13. Fastställande av arvoden för styrelseledamöter och d. Nya förslag. revisorer för räkenskapsåret 2017. 21. Årsavgiften. 14. Val av ordförande och styrelseledamot. a. Val av ordförande för 2017. -

The Blend of Normative Uncertainty and Commercial Immaturity in Swedish Ice Hockey

The Blend of Normative Uncertainty and Commercial Immaturity in Swedish Ice Hockey Re-submitted for publication in Sport in Society (February 2014). By describing and analysing normative uncertainties and the commercial immaturity in Swedish ice hockey (SHL/SIHA), this article focuses on the tension and dialectics in Swedish sport; increasingly greater commercial attempts (i.e., entrepreneurship, ‘Americanisation’, multi-arenas, innovations and public limited companies (plcs)) have to be mixed with a generally non-profit making organisation (e.g., the Swedish Sports Confederation) and its traditional values of health, democracy and youth sports and fosterage. In this respect, the elite ice hockey clubs are situated in a legal culture of two parallel norm systems: the tradition of self-regulation in sport and in civil law (e.g., commercial law). Indeed, the incoherent blend of idealism and commercialism in Swedish elite hockey appears to be fertile ground for hazardous (sports) management and indebtedness. This mix of ‘uncertainty’ and ’immaturity’ has given rise to various financial trickeries and negligence, which have subsequently developed into legal matters. Consequently, the legal system appears to have become a playground for Swedish ice hockey. This article reflects on the reasons and the rationale in this frictional development by focusing on a legal case that comes under the Business Reorganisation Act. The analysis reveals support for a ‘soft’ juridification process in Swedish ice hockey in order to handle the charging tension of the two parallel norm systems. Keywords: entrepreneurship, public limited company (plc.), non-profit-organisation, bankruptcy, business reorganisation, juridification. Introduction Swedish ice hockey, and particularly SHL, the premier league, is claimed to be the most commercially developed Swedish sport in terms of financial turnovers1 and commercial magnetism. -

Div. 5 Herrar Skall 2 Seriesegrare Beredas Plats I Div

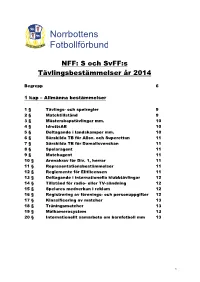

NFF: S och SvFF:s Tävlingsbestämmelser år 2014 Begrepp 6 1 kap – Allmänna bestämmelser 1 § Tävlings- och spelregler 9 2 § Matchtillstånd 9 3 § Mästerskapstävlingar mm. 10 4 § IdrottsAB 10 5 § Deltagande i landskamper mm. 10 6 § Särskilda TB för Allsv. och Superettan 11 7 § Särskilda TB för Damallsvenskan 11 8 § Spelaragent 11 9 § Matchagent 11 10 § Arenakrav för Div. 1, herrar 11 11 § Representationsbestämmelser 11 12 § Reglemente för Elitlicensen 11 13 § Deltagande i internationella klubbtävlingar 12 14 § Tillstånd för radio- eller TV-sändning 12 15 § Spelares medverkan i reklam 12 16 § Registrering av förenings- och personuppgifter 12 17 § Klassificering av matcher 13 18 § Träningsmatcher 13 19 § Målkamerasystem 13 20 § Internationellt samarbete om barnfotboll mm 13 1 2 kap - Administration Tävlingens genomförande 1 § Poängberäkning 14 2 § Placering i tävling 14 3 § Speltid 14 4 § Ersättare och avbytare 15 5 § Priser 15 6 § Seriesammansättning - serier 16 7 § Övriga distriktstävlingar 17 8 § Föreningars eget arr. av tävling/träningsmatch 17 8.1 Allmänt 8.2 Förutsättningar för nationella tillstånd 8.3 Internationella tävlingar och träningsmatcher 8.4 Internationell landskamp eller landslagsturnering i Sverige 9 § Anmälan till tävling 19 10 § Behörighet att anmäla lag till tävling 19 10.1 Allmänt 10.2 Kombinerade lag 10.3 Representationslag 11 § Anmälan av lag tillhörande nya föreningar 20 12 § Spelordning 20 13 § Matchändring 21 14 § Uppskjuten eller avbruten match 22 14.1 Uppskjuten/avbruten match pga. väderförhållanden mm. 14.2 Avbruten match pga. ordningsstörning 14.3 Match som återupptas 15 § Ordningsstörning – avbruten match 23 15.1 Tävling enligt seriemetoden 15.2 Tävling enligt utslagsmetoden 16 § Omspel av färdigspelad match 24 17 § Förening som utgår ur tävling/lämnar walk-over 25 18 § Ospelad match 26 19 § Upp- och nedflyttning 26 20 § Kval 29 20.1 Kvalordning avseende förbundsserierna 20.2 Kvalmetod i kval till div. -

Onside Tv Producti0n Ab Signs Deal with the Tv4 Group

PRESS RELEASE 2014-03-28 ONSIDE TV PRODUCTI0N AB SIGNS DEAL WITH THE TV4 GROUP Onside TV Production AB has signed an exclusive three-year agreement with the TV4 Group – with the rights to extend the deal – to produce roughly 350 football matches a year starting in 2014. The deal is estimated to be worth between EUR 4,5 million to 5,5 million per year. The agreement includes the TV production of every match in the Allsvenskan series (top division in Sweden), selected matches from Superettan (second division), women’s Allsvenskan as well as men’s national team friendly games. The games will be televised on TV4 Sport, TV12 and C More channels (all part of the TV4 Group). All the games will be televised in HD and will conform to the new digital media format. - We are extremely pleased to be part of the future development of TV broadcasts of Swedish football. Our goal is to elevate the quality of televised football in Sweden to the next level. With our new special cameras we will be able to offer our viewers an amazing experience watching football on TV, says Mr. Thomas Sturesson, Managing Director of Onside TV Production AB. - Choosing Onside as our production partner was only natural with their close association with football in Sweden along with their extensive experience and innovative approach as TV producers. Together, we will provide our viewers with top quality TV productions, says Johan Kleberg, Head of Content for the TV4 Group. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Onside TV Production AB (”Onside”), located in Solna (Stockholm) is a TV production company with a staff of more than 20. -

Bildandet Av Elitettan - Ett År Senare

Bildandet av Elitettan - ett år senare En kvalitativ studie av utvecklingen av svensk damfotbolls näst högsta serie Lindgren, Louise Nygren, Josefin Åhlander, Sanna Idrottsvetenskapligt examensarbete (2IV31E) 15 högskolepoäng Datum: 22-05-14 Handledare: Tobias Stark Examinator: Per-Göran Fahlström Bildandet av Elitettan – ett år senare En kvalitativ studie av utvecklingen av svensk damfotbolls näst högsta serie Abstrakt Titel: Bildandet av Elitettan – ett år senare - En kvalitativ studie av utvecklingen av svensk damfotbolls näst högsta serie Författare: Louise Lindgren, Josefin Nygren & Sanna Åhlander Examinator: Per-Göran Fahlström Datum: 2014–05–22 Nyckelord: Elitettan, damfotboll, ekonomi, talangutveckling Problemområde: Elitettan är svensk fotbolls näst högsta serie på damsidan och denna spelades för första gången år 2013. Den nya rikstäckande serien innebar betydligt längre resor för seriens föreningar och således också en betydande ökning av resekostnaderna. Syfte: Syftet med studien är att undersöka organiseringen av elitverksamheten inom svensk damfotboll. Mer precist handlar det om att belysa betydelsen av omvandlingen av landets näst högsta serie, från två geografiskt uppdelade enheter – i form av en Söder- och en Norretta – till en enda riksomfattande serie, Elitettan. Ambitionen är att både jämföra synen på serieomläggningen på fältet och begrunda dess effekter för de inblandade föreningarna. Metod: Studien har genomförts som en kvalitativ intervjuundersökning som baseras på intervjuer med personer på ledande positioner i sju olika föreningar i Elitettan samt två utomstående personer, Hanna Marklund, expert på svensk damfotboll samt Anna Nilsson från intresseorganisationen Elitfotboll Dam. Resultat: Resultatet av studien visar det går att urskilja tydliga samband mellan synsättet på serieomläggningen och vilken historia samt var någonstans föreningarna befinner sig geografiskt. -

Mediaguide 2017

NORWAY MEDIAGUIDE 2017 MEDIAGUIDE NORWAY 1 Ingrid Schjelderup and the rest of the team. FACTS Photo: Getty Images IN NORWAY Terje Svendsen Pål Bjerketvedt President General Secretary FACTS INTERNATIONAL HONOURS WOMEN'S FOOTBALL Population 5 267 146 Olympic Tournament Gold medal 2000 Number of clubs 1 842 Bronze medal 1996 Number of teams (incl. Futsal) 30 414 FIFA World Cup Gold medal 1995 Number of female players 103 636 Silver medal 1991 Number of referees 2 927 UEFA European Championship Gold medal 1987 and 1993 Year of foundation 1902 (April 30) Silver medal 1989, 1991, 2005 and 2013 Bronze medal 1995, 2001 and 2009 Affiliated to FIFA 1908 Name of National Stadium Ullevaal Stadium FIFA World Tournament Gold medal 1988 Capacity of National Stadium 27 200 (all seated) Season March-November NATIONAL LEAGUE- AND CUP CHAMPION National colours Shirt: Red League winner 2016 LSK Kvinner Shorts: White Cup winner 2016 LSK Kvinner Socks: Blue/red League winners (84-16) Trondheims-Ørn (7), Asker (6), Røa (5), Address The Football Association of Norway Sprint/Jeløy (4), LSK Kvinner (4) , Kolbotn (3), Stabæk (2), Nymark (1), Klepp (1). Ullevaal Stadion N-0840 Oslo NORWAY Cup winners (78-16) Trondheims-Ørn (8), BUL (5), Asker (5), Telephone +47 21 02 93 00 Røa (5), Sprint/Jeløy (4), Stabæk (3), LSK Kvinner (3), Bøler (1), Klepp (1), Setskog/ Telefax +47 21 02 93 01 Høland (1), Sandviken (1), Medkila (1), Internet home page www.fotball.no Kolbotn (1) 2 MEDIAGUIDE NORWAY XXXXXXMARTIN XXXXSJÖGREN Date of Birth: 7. April 1977 FACTS WITH THE NORWEGIAN