A Multiphase Mixed Methods Analysis of UK E-Commerce Privacy Policies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sustainability in the Power Sector 2010 Update Europe

Sustainability in the Power Sector 2010 Update - Europe Tim Steinweg, Albert ten Kate & Kristóf Rácz November 2010 Sustainability in the Power Sector 2010 Update - Europe Sustainability in the Power Sector 2010 update: Europe Tim Steinweg, Albert ten Kate & Kristóf Rácz (SOMO) Amsterdam, November 2010 1 Colophon Sustainability in the Power Sector 2010 Update - Europe November 2010 Authors: Tim Steinweg, Albert ten Kate & Kristóf Rácz Cover design: Annelies Vlasblom ISBN: 978-90-71284-63-2 Funding This publication has been produced with the financial assistance of Greenpeace Nederland. The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of SOMO and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of Greenpeace Nederland. Published by Stichting Onderzoek Multinationale Ondernemingen Centre for Research on Multinational Corporations Sarphatistraat 30 1018 GL Amsterdam The Netherlands Tel: + 31 (20) 6391291 Fax: + 31 (20) 6391321 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.somo.nl This document is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivateWorks 2.5 License. 2 Sustainability in the Power Sector 2010 Update - Europe Contents Contents .......................................................................................................................... 3 List of Figures................................................................................................................. 5 List of Tables .................................................................................................................. 5 Abbreviations -

Artista - Titulo Estilo PAIS PVP Pedido

DESCUENTOS TIENDAS DE MUSICA 5 Unidades 3% CONSULTAR PRECIOS Y 10 Unidades 5% CONDICIONES DE DISTRIBUCION 20 Unidades 9% e-mail: [email protected] 30 Unidades 12% Tfno: (+34) 982 246 174 40 Unidades 15% LISTADO STOCK, actualizado 09 / 07 / 2021 50 Unidades 18% PRECIOS VALIDOS PARA PEDIDOS RECIBIDOS POR E-MAIL REFERENCIAS DISPONIBLES EN STOCK A FECHA DEL LISTADOPRECIOS CON EL 21% DE IVA YA INCLUÍDO Referencia Sello T Artista - Titulo Estilo PAIS PVP Pedido 3024-DJO1 3024 12" DJOSER - SECRET GREETING EP BASS NLD 14.20 AAL012 9300 12" EMOTIVE RESPONSE - EMOTIONS '96 TRANCE BEL 15.60 0011A 00A (USER) 12" UNKNOWN - UNTITLED TECHNO GBR 9.70 MICOL DANIELI - COLLUSION (BLACKSTEROID 030005V 030 12" TECHNO ITA 10.40 & GIORGIO GIGLI RMXS) SHINEDOE - SOUND TRAVELLING RMX LTD PURE040 100% PURE 10" T-MINIMAL NLD 9.60 (RIPPERTON RMX) BART SKILS & ANTON PIEETE - THE SHINNING PURE043 100% PURE 12" T-MINIMAL NLD 8.90 (REJECTED RMX) DISTRICT ONE AKA BART SKILS & AANTON PURE045 100% PURE 12" T-MINIMAL NLD 9.10 PIEETE - HANDSOME / ONE 2 ONE DJ MADSKILLZ - SAMBA LEGACY / OTHER PURE047 100% PURE 12" TECHNO NLD 9.00 PEOPLE RENATO COHEN - SUDDENLY FUNK (2000 AND PURE088 100% PURE 12" T-HOUSE NLD 9.40 ONE RMX) PURE099 100% PURE 12" JAY LUMEN - LONDON EP TECHNO NLD 10.30 DILO & FRANCO CINELLI - MATAMOSCAS EP 11AM002 11:00 A.M. 12" T-MINIMAL DEU 9.30 (KASPER & PAPOL RMX) FUNZION - HELADO EN GLOBOS EP (PAN POT 11AM003 11:00 A.M. 12" T-MINIMAL DEU 9.30 & FUNZION RMXS) 1605 MUSIC VARIOUS ARTISTS - EXIT PEOPLE REMIXES 1605VA002 12" TECHNO SVN 9.30 THERAPY (UMEK, MINIMINDS, DYNO, LOCO & JAM RMXS) E07 1881 REC. -

Q1. (A) Figure 1 Shows a Sheet of Card. Figure 1 Describe How to Find the Centre of Mass of This Sheet of Card. You May Draw

Q1. (a) Figure 1 shows a sheet of card. Figure 1 Describe how to find the centre of mass of this sheet of card. You may draw diagrams as part of your answer. ........................................................................................................................ ........................................................................................................................ ........................................................................................................................ ........................................................................................................................ ........................................................................................................................ ........................................................................................................................ ........................................................................................................................ ........................................................................................................................ ........................................................................................................................ ........................................................................................................................ ........................................................................................................................ ....................................................................................................................... -

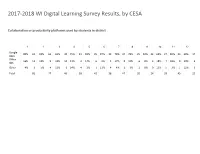

2017-2018 WI Digital Learning Survey Results, by CESA

2017-2018 WI Digital Learning Survey Results, by CESA Collaboration or productivity platforms used by students in district 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Google 80% 65 83% 64 65% 30 75% 21 83% 35 87% 33 79% 37 78% 25 92% 22 69% 27 80% 36 68% 17 Apps Office 16% 13 12% 9 22% 10 11% 3 14% 6 3% 1 17% 8 19% 6 8% 2 18% 7 18% 8 20% 5 365 Other 4% 3 5% 4 13% 6 14% 4 2% 1 11% 4 4% 2 3% 1 0% 0 13% 5 2% 1 12% 3 Total 81 77 46 28 42 38 47 32 24 39 45 25 Grade levels where most or all social media sites are blocked 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 K 9% 48 9% 54 8% 28 8% 17 9% 30 9% 29 8% 34 8% 26 9% 17 8% 22 8% 29 7% 11 1 9% 47 9% 54 8% 28 8% 17 9% 30 9% 29 8% 34 8% 26 9% 17 8% 22 8% 29 7% 11 2 9% 47 9% 54 8% 28 8% 17 9% 30 9% 29 8% 34 8% 26 9% 17 8% 22 8% 29 7% 11 3 9% 47 9% 54 8% 27 8% 17 8% 28 9% 29 8% 33 8% 26 9% 17 8% 22 8% 29 7% 11 4 9% 47 9% 54 8% 27 8% 17 8% 28 9% 29 8% 33 8% 26 9% 16 8% 22 8% 29 7% 11 5 9% 46 9% 53 8% 27 7% 16 8% 27 9% 29 8% 32 8% 26 9% 16 8% 21 8% 27 7% 11 6 8% 44 9% 51 8% 26 8% 17 7% 25 8% 28 8% 33 8% 24 8% 15 7% 20 8% 27 7% 11 7 8% 43 9% 51 8% 26 8% 17 7% 25 8% 27 8% 33 7% 23 7% 13 7% 19 8% 27 7% 11 8 8% 44 9% 50 8% 26 8% 17 7% 25 8% 27 8% 32 7% 23 7% 12 7% 19 8% 27 7% 11 9 5% 26 4% 25 7% 24 8% 17 7% 23 6% 20 7% 27 7% 23 5% 10 7% 18 6% 23 7% 11 10 5% 26 4% 25 7% 24 8% 17 6% 22 6% 20 7% 27 7% 23 5% 10 7% 18 6% 23 7% 11 11 5% 26 4% 24 7% 24 8% 17 6% 22 6% 20 7% 27 7% 23 5% 10 7% 18 6% 23 7% 11 12 5% 26 4% 24 7% 23 8% 17 6% 22 6% 20 7% 27 7% 23 5% 10 7% 18 6% 23 7% 11 None 2% 13 2% 9 1% 3 1% 3 1% 5 1% 3 0% 2 0% 0 2% 4 3% 7 3% 9 3% 5 -

10 Total 11 Total 6 Total 7 Total 5 Total 3 Total 42 Grand Total

Advocacy/Policy Programing Data/Coordinated Entry Housing First Health Care Reform Self Care/Skill Building Housing Alliance:: Michele Thomas and Ben Miksch and Building Changes: Kari Murphy DESC & US Interagency Council on Homelessness: Bill DESC & Corporation for Supportive Housing, Debbie Buidling Changes DSHS CA: Jeanne McShane A Coordinated Entry Toolkit: Tips on Designing and Hobson & Richard Cho Thiele & Daniel Malone 2013 Housing and Homelessness Policy Briefing Partnerships to Increase Community Involovement & Implementing a Coordinated Entry System in your History & Overview of Housing, and Model First Healthcare Reform implications for Housing First Ken Kraybll - Self care and secondary Trauma Housing Stability for Families in CA Coutny Movement Providers (Broaden Title) LEAD: SARAH Real Change: Tim Harris & Faith and Family Building Changes/Spokane: Kari Murphy and Shelia Opportunity Council & Serentiy House of Clallam Clark County Dep of Comm Services: Kate Budd & DESC CCS: Erin Maguire Homelessness Project Participants Mroley County: Greg Winter & Kathy Wahto Christina Clayton Building Natural Supports & Strengthening Family Using public space and creative methods to raise Vocies from the Field: Coordinated Entry in Practice - Housing First in Rural and Suburban Communities Building a SOAR Initiative & Sustaining Relationships: Groundwork Wraparound Services with awareness about homelessness Putting Spokane here also large city, and rural area LEAD: Kate (to ensure we combine workshops Ken Kraybll -motiviational interviwing: -

Kallendresser#4

# 04 / € 4,00 ne kölsche UltrA-Zine / Coloniacs Interviews: Kölsche Mythos, Racaille Verte Gruppendiskussion: FC-Reloaded Stadt & Kultur: Sound of Cologne, Street Art Global Village: Paris, Italien, Japan, Australien Ultrà: Fandemo, Tattoos, Jonas Gabler FC: Hinrunde 2010, Vereinspolitik EDITORIAL 03 Seid gegrüßt! Schon wieder haben wir es nicht geschafft, pünktlich zum Start der Rückrunde den neuen Kallendresser an den Start zu bringen. Schande über unsere Häupter … Dabei hatten wir uns fest vorgenommen, diesmal Textabgabefristen besser einzuhalten, doch der Winter war verdammt kalt und die Winterpause erschreckend kurz. Hinzu kam die derzeitige sportliche und vereinsinterne Misere, die uns ein wenig die Lust am Schreiben nahmen. Fest vorgenommen hatten wir uns auch, den Kallendresser etwas zu entschlacken, weniger Seiten zum Drucker zu bringen – auch hier haben wir versagt. Ihr haltet nun die vierte Ausgabe unseres Ultràzines in der Hand, und wir hoffen, dass Euch die Inhalte weiterhin zusagen. Spart nicht mit Kritik – wir hoffen, auf einige bisherige Kritiker kleine Schritte zugegangen zu sein. Der Fokus des neuen Heftes liegt – wen wundert es – zu großen Teilen auf der aktu- ellen Vereinspolitik. Aber auch Themen, die uns in den vergangenen sechs Monaten beschäftigen, wie der Erfolg der Fandemo in Berlin, sollen in dieser Ausgabe nicht zu kurz kommen. Wir hoffen Euch einen interessanten Einblick in unsere immer noch junge Gruppe geben zu können. Wir Coloniacs sind immer noch in der Findungs- phase, blicken aber optimistisch in die oft ungewiss scheinende Zukunft der Kölner Fanszene und der Ultràbewegung. Eine Bitte noch: Wir würden uns sehr darüber freuen, wenn Ihr uns Feedback gebt. Versteht Euch auch dazu aufgerufen, uns Texte, Geschichten, Anregungen, Kritiken und Leserbriefe an [email protected] zuzuschicken, egal ob nun als Fan des 1. -

Bear Harvest Map 2018

2018 Bear Harvest General 18 Extended 11 Total 29 Archery 10 Archery 12 Archery 8 Archery 4 General 59 Archery 25 General 13 General 48 Archery 16 General 51 Extended 3 General 63 General 91 Extended 21 Archery 3 Extended 11 Extended 41 Archery 15 Total 72 Extended 30 Extended 50 Total 46 General 60 Total 67 Total 96 General 30 Total 109 Total 166 Extended 16 Extended 25 Total 79 Total 70 Archery 14 Archery 3 Archery 5 General 27 General 56 Archery 4 Archery 8 General 62 Extended 10 Total 70 General 32 General 20 Archery 13 Archery 7 Total 67 Total 40 Extended 6 Archery 10 General 78 General 47 Archery 23 Extended 17 General 51 Total 53 Total 34 General 13 Extended 5 Total 54 Archery 21 General 109 Extended 43 Total 13 Total 96 General 128 Extended 27 Total 104 Extended 9 Total 159 Archery 25 Archery 11 Total 158 General 54 General 41 Archery 10 Extended 26 Early 2 Total 52 General 69 General 1 Total 105 Archery 17 Total 79 Extended 1 Archery 3 General 50 Archery 6 Archery 5 General 20 Extended 34 Archery 1 Total 2 Archery 11 General 80 Archery 11 General 15 Extended 15 Total 103 Total 1 Extended 15 General 32 Archery 7 Extended 1 General 52 Total 38 Extended 24 Total 35 Extended 17 General 19 Total 87 Early 4 Archery 7 Total 87 Archery 1 Total 60 Total 26 Archery 2 Archery 5 General 26 Archery 6 General 17 Archery 9 Total 33 General 10 General 3 Extended 6 General 3 Extended 1 General 20 Extended 13 Extended 2 Total 24 Extended 5 Total 1 Extended 21 Early 1 Total 17 Archery 2 Archery 3 Total 29 Total 7 Total 50 General 3 General 32 General -

2017 Lacrosse Media Guide.Indd

2017 COLORADO BUFFALOES Numerical No. Name Pos. Ht. Yr. Hometown/Previous School (High School) Pronunciation 1 Paige Soenksen G 5-10 Sr. Encinitas, Calif./La Costa Canyon H.S. SONK-sen 2 Marie Moore M 5-7 Sr. Brick, N.J./Brick Memorial H.S. 3 Sophia Castillo A 5-4 So. Allentown, Pa./Parkland H.S. 4 Claire McCain M 5-2 Sr. Winnetka, Ill./New Trier H.S. 5 Cali Castagnola A 5-7 Sr. Alamo, Calif./Carondelet H.S. 6 Kelsie Garrison D 5-8 Jr. Westlake Village, Calif./Agoura H.S. 7 Tori Link M 5-8 Sr. Englewood, Colo./Cherry Creek H.S. 8 Amanda Salvadore M 5-0 Sr. Monroe Township, N.J./Monroe Township H.S. SAL-vah-dor 9 Carly Cox A 5-8 Jr. Bay Shore, N.Y./Bay Shore H.S. 10 Emily Knapp A/M 5-5 Sr. Fair Haven, N.J./Rumson - Fair Haven Regional H.S. NAPP 11 Samantha Nemirov A 5-0 So. Setauket, N.Y./Ward Melville H.S. NEM-er-ov 13 Katie Macleay A 5-3 Sr. Annapolis, Md./Annapolis H.S. mac-LAY 14 Maddie Hunt D 5-5 Sr. Catonsville, Md./Catonsville H.S. 15 Julia Sarcona A 5-8 Jr. Northport, N.Y./Northport H.S. sar-CONE-ah 16 Johnna Fusco A 5-4 Sr. Marietta, Ga./Lassiter H.S. FEW-skoh 17 Miranda Stinson M 5-4 So. Manakin Sabot, Va./Trinity Episcopal H.S. 18 Amelia Brown D 5-5 Sr. Hingham, Mass./Notre Dame Academy 19 Sydney Evensen D 5-5 Jr. -

Total 1 100,00 $ (1) 384,00

Destinataire Sommes : Nom, Prénom (1) Sommes versées directement Ville (2) Sommes versées indirectement Code Postal – 3 premiers caractères (3) Transfert de valeur total (en $ CA) (1) 10 230,00 $ ANGEL, JONATHAN OTTAWA (2) 0,00 $ K1H (3) Total 10 230,00 $ (1) 1 100,00 $ ARBESS, GORDON TORONTO (2) 0,00 $ M4X (3) Total 1 100,00 $ (1) 384,00 $ BARDAI, SHELINA TORONTO (2) 0,00 $ M5G (3) Total 384,00 $ (1) 6 600,00 $ BARIL, JEAN-GUY MONTRÉAL (2) 0,00 $ H2L (3) Total 6 600,00 $ (1) 1 260,00 $ BIGGIN, BROOK EDMONTON (2) 0,00 $ T5K (3) Total 1 260,00 $ (1) 420,00 $ BOMBARDIER, MATHILDE MONTRÉAL (2) 0,00 $ H2K (3) Total 420,00 $ (1) 5 500,00 $ BONDY, GREGORY VANCOUVER (2) 0,00 $ V6Z (3) Total 5 500,00 $ BRADFORD, GLEN (1) 700,00 $ VANCOUVER (2) 0,00 $ V6B (3) Total 700,00 $ (1) 740,00 $ BRENNAN, EVANNA VANCOUVER (2) 0,00 $ V6J (3) Total 740,00 $ (1) 3 630,00 $ BRUNETTA, JASON TORONTO (2) 0,00 $ M5G (3) Total 3 630,00 $ (1) 3 245,00 $ CHANO, FRÉDÉRIC MONTRÉAL (2) 0,00 $ H2L (3) Total 3 245,00 $ (1) 1 120,00 $ CHOWN, SARAH VICTORIA (2) 0,00 $ V8T (3) Total 1 120,00 $ (1) 2 750,00 $ CONWAY, BRIAN VANCOUVER (2) 0,00 $ V6Z (3) Total 2 750,00 $ (1) 2 750,00 $ COOPER, CURTIS OTTAWA (2) 0,00 $ K1H (3) Total 2 750,00 $ (1) 3 025,00 $ COSTINIUK, CECILIA MONTRÉAL (2) 0,00 $ H4A (3) Total 3 025,00 $ (1) 1 400,00 $ COTNAM, JASMINE THUNDER BAY (2) 981,85 $ P7C (3) Total 2 381,85 $ (1) 18 920,00 $ COX, JOSEPH MONTRÉAL (2) 0,00 $ H4A (3) Total 18 920,00 $ (1) 420,00 $ DART, GARRY HALIFAX (2) 0,00 $ B3J (3) Total 420,00 $ (1) 1 400,00 $ DAVIS, RANDY BARRIE (2) -

Rice University

RICE UNIVERSITY Football 2010 Fact Book University Information Assistant Head Coach/Defensive Coordinator l Assistant Athletics Director/Football Operations l Chuck Driesbach l Jerry Pickle Rice Fact Book Contents Location l Houston, Texas 77251 Rice Football Rosters 2 Alma Mater l Villanova, ‘75 Alma Mater l Delta State, ‘76 Founded l 1891 Rice Player Biographies 6 Offensive Coodinator l David Beaty Defensive Graduate Assistant l Michael Slater Enrollment l 5,556 Rice Coaching Staff Biographies 66 Alma Mater l Lindenwood College, ‘94 Alma Mater l Texas State, ‘93 Nickname l Owls 2009 Statistics 80 Defensive Line/Special Teams Coordinator l Offensive Graduate Assistant l David Sloan Mascot l Sammy the Owl 2009 Review 96 Craig Naivar Alma Mater l New Mexico, ‘95 Colors l Blue (pms 281c) and Gray (pms 424c) Rice Record Book 120 Alma Mater l Hardin-Simmons, ‘94 Conference l Conference USA Post-Season Honors 158 Stadium l Rice Stadium (47,000) Wide Receivers l Larry Edmondson Team Information Alma Mater l Texas A&M, ‘83 Rice Letterman List 169 Playing Surface l FieldTurf Duraspine 2009 Record l 2-10 Running Backs/Recruiting Coordinator l All-Time Results 192 President l David W. Leebron (Harvard, ‘76) C-USA Record/Finish l 2-6/5th-West Division Rick LaFavers Series Records 204 Athletics Director l Rick Greenspan (Maryland, ‘75) Starters Returning/Lost l 17/5 Bowl History 208 Athletics Phone Number l 713.348.6920 Alma Mater l TCU, ‘97 Offense l 9/2 Ticket Office Numberl 713.522.OWLS Linebackers l Darrell Patterson Defense l 8/3 Mailing Address l P.O. -

This Dissertation Has Been Microfilmed Exactly As Received University

This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received Mic 60-6373 HINTON, Jr., William G. VOCAL COMPETENCIES DESIRABLE FOR PUBLIC SCHOOL MUSIC TEACHING AND THEIR RELATION TO CLASS VOICE INSTRUCTION IN TEACHER EDUCATION. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1960 M usic University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan VOCAL COMPETENCIES DESIRABLE FOR PUBLIC SCHOOL MUSIC TEACHING AND THEIR RELATION TO CLASS VOICE INSTRUCTION IN TEACHER EDUCATION DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By WILLIAM G. HINTON, JR., B.S.Ed., M.Mus. ***** The Ohio State University I960 Approved by Co-Advisers Department of Education and the School of Music ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The writer thanks Professor William B. McBride for his wise counsel and encouragement in the preparation of this dissertation. Professor Earl W. Anderson has been most kind and helpful. Assistant Professor David McKenna's editorial advice has been exceptionally constructive and is deeply appreciated by the writer. The assistance given the writer by the many public school music supervisors and college music educators has furnished most of the data upon which this dissertation is based. The writer's warm thanks goes out to each of them. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION . ............... 1 The Problem ............ 1 Statement of the Problem .... 3 Specific Objectives of the Study 3 Definitions . ............... 4 Survey of the Literature . ............... 4 Identification of Competencies ........... 5 Class Voice Instruction in Higher Education 7 Need for the Study 13 Procedural Techniques ....... 16 Design of the Research Instrument • * 16 Selection of Population .