This Dissertation Has Been Microfilmed Exactly As Received University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Analysis of Honegger's Cello Concerto

AN ANALYSIS OF HONEGGER’S CELLO CONCERTO (1929): A RETURN TO SIMPLICITY? Denika Lam Kleinmann, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2014 APPROVED: Eugene Osadchy, Major Professor Clay Couturiaux, Minor Professor David Schwarz, Committee Member Daniel Arthurs, Committee Member John Holt, Chair of the Division of Instrumental Studies James Scott, Dean of the School of Music Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Kleinmann, Denika Lam. An Analysis of Honegger’s Cello Concerto (1929): A Return to Simplicity? Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2014, 58 pp., 3 tables, 28 examples, 33 references, 15 titles. Literature available on Honegger’s Cello Concerto suggests this concerto is often considered as a composition that resonates with Les Six traditions. While reflecting currents of Les Six, the Cello Concerto also features departures from Erik Satie’s and Jean Cocteau’s ideal for French composers to return to simplicity. Both characteristics of and departures from Les Six examined in this concerto include metric organization, thematic and rhythmic development, melodic wedge shapes, contrapuntal techniques, simplicity in orchestration, diatonicism, the use of humor, jazz influences, and other unique performance techniques. Copyright 2014 by Denika Lam Kleinmann ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES………………………………………………………………………………..iv LIST OF MUSICAL EXAMPLES………………………………………………………………..v CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION………..………………………………………………………...1 CHAPTER II: HONEGGER’S -

December 1940) James Francis Cooke

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 12-1940 Volume 58, Number 12 (December 1940) James Francis Cooke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Music Education Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, Music Performance Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation Cooke, James Francis. "Volume 58, Number 12 (December 1940)." , (1940). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/59 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. —— THE ETUDE Price 25 Cents mueie magazine i — ' — ; — i——— : ^ as&s&2i&&i£'!%i£''££. £&. IIEHBI^H JDiauo albums fcj m Christmas flarpms for JfluStc Jfolk IS Cljiistmas iSnraaiitS— UNTIL DECEMBER 31, 1940 ONLY) (POSTPAID PRICES GOOD CONSOLE A Collection Ixecttalist# STANDARD HISTORY OF AT THE — for £111 from Pegtnner# to CHILD’S OWN BOOK OF of Transcriptions from the Masters Revised Edition PlAVUMfl MUSIC—Latest, GREAT MUSICIANS for the Pipe Organ or Electronic DECEMBER 31, 1940 By James Francis Cooke Type of Organ Compiled and MYllfisSiiQS'K PRICES ARE IN EFFECT ONLY UP TO By Thomas -

Cultural Influences of Organ Music Composed by African American Women Author(S): Carol Rittersource: College Music Symposium , Vol

Cultural Influences of Organ Music Composed by African American Women Author(s): Carol RitterSource: College Music Symposium , Vol. 55 (2015) Published by: College Music Society Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/26574395 JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms College Music Society is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to College Music Symposium This content downloaded from 86.59.13.237 on Thu, 08 Jul 2021 11:46:58 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Cultural Influences of Organ Music Composed by African American Women Carol Ritter Volume 55 2015 Cultural Influences on Organ Music Written By African American Women 1 Abstract In this paper, major events in African American history are described and contrasted with the history of organ music written by African American women in the twentieth- and the twenty-first centuries. The discussion includes the emergence of women's rights, especially women composers. The author traces the beginnings of African American women composers from church music to all other forms of musical performance. Included in the paper are the history, works, and styles of Florence Price (1887-1953), Undine Smith Moore (1905-1989), Zenobia Powell Perry (1908-2004), Betty Jackson King (1928-1994), Shirley Scott (1934-2002), Judith Marie Baity (b. -

Sustainability in the Power Sector 2010 Update Europe

Sustainability in the Power Sector 2010 Update - Europe Tim Steinweg, Albert ten Kate & Kristóf Rácz November 2010 Sustainability in the Power Sector 2010 Update - Europe Sustainability in the Power Sector 2010 update: Europe Tim Steinweg, Albert ten Kate & Kristóf Rácz (SOMO) Amsterdam, November 2010 1 Colophon Sustainability in the Power Sector 2010 Update - Europe November 2010 Authors: Tim Steinweg, Albert ten Kate & Kristóf Rácz Cover design: Annelies Vlasblom ISBN: 978-90-71284-63-2 Funding This publication has been produced with the financial assistance of Greenpeace Nederland. The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of SOMO and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of Greenpeace Nederland. Published by Stichting Onderzoek Multinationale Ondernemingen Centre for Research on Multinational Corporations Sarphatistraat 30 1018 GL Amsterdam The Netherlands Tel: + 31 (20) 6391291 Fax: + 31 (20) 6391321 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.somo.nl This document is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivateWorks 2.5 License. 2 Sustainability in the Power Sector 2010 Update - Europe Contents Contents .......................................................................................................................... 3 List of Figures................................................................................................................. 5 List of Tables .................................................................................................................. 5 Abbreviations -

Artista - Titulo Estilo PAIS PVP Pedido

DESCUENTOS TIENDAS DE MUSICA 5 Unidades 3% CONSULTAR PRECIOS Y 10 Unidades 5% CONDICIONES DE DISTRIBUCION 20 Unidades 9% e-mail: [email protected] 30 Unidades 12% Tfno: (+34) 982 246 174 40 Unidades 15% LISTADO STOCK, actualizado 09 / 07 / 2021 50 Unidades 18% PRECIOS VALIDOS PARA PEDIDOS RECIBIDOS POR E-MAIL REFERENCIAS DISPONIBLES EN STOCK A FECHA DEL LISTADOPRECIOS CON EL 21% DE IVA YA INCLUÍDO Referencia Sello T Artista - Titulo Estilo PAIS PVP Pedido 3024-DJO1 3024 12" DJOSER - SECRET GREETING EP BASS NLD 14.20 AAL012 9300 12" EMOTIVE RESPONSE - EMOTIONS '96 TRANCE BEL 15.60 0011A 00A (USER) 12" UNKNOWN - UNTITLED TECHNO GBR 9.70 MICOL DANIELI - COLLUSION (BLACKSTEROID 030005V 030 12" TECHNO ITA 10.40 & GIORGIO GIGLI RMXS) SHINEDOE - SOUND TRAVELLING RMX LTD PURE040 100% PURE 10" T-MINIMAL NLD 9.60 (RIPPERTON RMX) BART SKILS & ANTON PIEETE - THE SHINNING PURE043 100% PURE 12" T-MINIMAL NLD 8.90 (REJECTED RMX) DISTRICT ONE AKA BART SKILS & AANTON PURE045 100% PURE 12" T-MINIMAL NLD 9.10 PIEETE - HANDSOME / ONE 2 ONE DJ MADSKILLZ - SAMBA LEGACY / OTHER PURE047 100% PURE 12" TECHNO NLD 9.00 PEOPLE RENATO COHEN - SUDDENLY FUNK (2000 AND PURE088 100% PURE 12" T-HOUSE NLD 9.40 ONE RMX) PURE099 100% PURE 12" JAY LUMEN - LONDON EP TECHNO NLD 10.30 DILO & FRANCO CINELLI - MATAMOSCAS EP 11AM002 11:00 A.M. 12" T-MINIMAL DEU 9.30 (KASPER & PAPOL RMX) FUNZION - HELADO EN GLOBOS EP (PAN POT 11AM003 11:00 A.M. 12" T-MINIMAL DEU 9.30 & FUNZION RMXS) 1605 MUSIC VARIOUS ARTISTS - EXIT PEOPLE REMIXES 1605VA002 12" TECHNO SVN 9.30 THERAPY (UMEK, MINIMINDS, DYNO, LOCO & JAM RMXS) E07 1881 REC. -

Faurã©, Through Boulanger, to Copland: the Nature of Influence

Gamut: Online Journal of the Music Theory Society of the Mid-Atlantic Volume 4 Issue 1 Article 9 January 2011 Fauré, through Boulanger, to Copland: The Nature of Influence Edward R. Phillips [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/gamut Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Phillips, Edward R. (2011) "Fauré, through Boulanger, to Copland: The Nature of Influence," Gamut: Online Journal of the Music Theory Society of the Mid-Atlantic: Vol. 4 : Iss. 1 , Article 9. Available at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/gamut/vol4/iss1/9 This A Music-Theoretical Matrix: Essays in Honor of Allen Forte (Part III), edited by David Carson Berry is brought to you for free and open access by Volunteer, Open Access, Library Journals (VOL Journals), published in partnership with The University of Tennessee (UT) University Libraries. This article has been accepted for inclusion in Gamut: Online Journal of the Music Theory Society of the Mid-Atlantic by an authorized editor. For more information, please visit https://trace.tennessee.edu/gamut. FAURÉ, THROUGH BOULANGER, TO COPLAND: THE NATURE OF INFLUENCE EDWARD R. PHILLIPS Nymphs of the woods, Goddesses of the fountains, Expert singers of all nations, Change your voices, So clear and high, To cutting cries and lamentations Since Atropos, the very terrible satrap, Has caught in her trap your Ockeghem, True treasure of music . Dress in your clothes of mourning, Josquin, Piersson, Brumel, Compère, And cry great tears of sorrow for having lost Your dear father. n the late fifteenth century, Josquin set this text—“Nymphes des bois,” La déploration sur la I mort de Johannes Ockeghem—as a commemoration of the older composer, “le bon père” of Josquin and his contemporaries Brumel, Compère, and Pierre de la Rue. -

Various Kompakt 100 Mp3, Flac, Wma

Various Kompakt 100 mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic Album: Kompakt 100 Country: Germany Released: 2004 Style: Minimal, Tech House, Ambient MP3 version RAR size: 1637 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1692 mb WMA version RAR size: 1479 mb Rating: 4.2 Votes: 639 Other Formats: ASF VOC FLAC WMA MIDI AIFF APE Tracklist Hide Credits Because Before (The Orb) 1-01 –Ulf Lohmann 4:52 Remix – The Orb Because (Thomas/Mayer) 1-02 –Ulf Lohmann 6:05 Remix – Mayer*, Thomas* Zu Dicht Dran (DJ Koze) 1-03 –Reinhard Voigt 4:37 Remix – DJ Koze Radeln (Sascha Funke) 1-04 –Thomas Fehlmann 6:03 Remix – Sascha Funke Weiche Zäune (The Modernist) 1-05 –Justus Köhncke 5:01 Remix – The Modernist 17&4 (Joachim Spieth) 1-06 –M.Mayer* 5:29 Remix – Joachim Spieth Tomorrow (Kaito) 1-07 –Superpitcher 6:17 Remix – Kaito Robson Ponte (Wassermann) 1-08 –Reinhard Voigt 4:08 Remix – Wassermann Respect To The Distance (Markus Guentner) 1-09 –Kaito 5:39 Remix – Markus Guentner One Two Three No Gravity (Dettinger) 1-10 –Closer Musik 5:05 Remix – Dettinger Pensum (Markus Guentner) 2-01 –M.Mayer* 5:39 Remix – Markus Guentner Frei/Hot Love (Justus Köhncke Feat. Meloboy) 2-02 –Freiland 4:13 Remix – Justus KöhnckeVocals – Meloboy Teaser (SCSI 9) 2-03 –Lawrence 6:33 Remix – SCSI 9* The World Is Crazy (Jürgen Paape) 2-04 –Schaeben&Voss* 4:52 Remix – Jürgen Paape 2-05 –Schaeben&Voss* Dicht Dran (Schaeben&Voss) 5:41 Intershop (Jonas Bering) 2-06 –Dettinger 5:46 Remix – Jonas Bering Megamix (Reinhard Voigt) 2-07 –Closer Musik 6:04 Mixed By – Reinhard Voigt Cero Uno (Matias Aguayo/Leandro Fresco) 2-08 –Leandro Fresco 6:42 Remix – Leandro Fresco, Matias Aguayo Tomorrow (SCSI 9) 2-09 –Superpitcher 6:47 Remix – SCSI 9* Intershop (Ulf Lohmann) 2-10 –Dettinger 3:08 Remix – Ulf Lohmann In Moll (Hannes Teichmann) 2-11 –Markus Guentner 7:16 Remix – Hannes Teichmann Companies, etc. -

The Music of Randall Thompson a Documented

THE MUSIC OF RANDALL THOMPSON (1899-1984) A DOCUMENTED CATALOGUE By Carl B. Schmidt Elizabeth K. Schmidt In memory of RANDALL THOMPSON ' for VARNEY THOMPSON ELLIOTT (†) CLINTON ELLIOTT III EDWARD SAMUEL WHITNEY THOMPSON (†) ROSEMARY THOMPSON (†) RANDALL THOMPSON JR. HAROLD C. SCHMIDT (†) and for E. C. SCHIRMER MUSIC COMPANY a division of ECS Publishing Group © 2014 by E. C. Schirmer Music Company, Inc., a division of ECS Publishing 1727 Larkin Williams Road, Fenton, MO 63026-2024 All rights reserved. Published 2014 Printed in the United States of America ISBN 978-0-911318-02-9 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Schmidt, Carl B. The music of Randall Thompson (1899-1984) : a documented catalogue / by Carl B. Schmidt [and] Elizabeth K. Schmidt. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-911318-02-9 1. Thompson, Randall, 1899-1984--Bibliography. I. Schmidt, Elizabeth K. II. Title. ML134.T42S36 2015 016.78092--dc23 2014044640 Since I first went to Rome in 1922, Italian culture, the Italian people and the Italian language have been the strongest single influence on my intellectual and artistic development as a person and as a composer. So true is this that I cannot imagine what my life would be without all the bonds that bind me in loyalty and devotion to Italy and to my Italian friends. 13 June 1959 letter from Thompson to Alfredo Trinchieri Thompson always makes you think there is nothing as beautiful, as rich, or as varied as the sounds of the human voice. Alfred Frankenstein, San Francisco Chronicle (24 May 1958) It is one of the lovely pieces our country has produced, that any country, indeed, has produced in our century. -

Q1. (A) Figure 1 Shows a Sheet of Card. Figure 1 Describe How to Find the Centre of Mass of This Sheet of Card. You May Draw

Q1. (a) Figure 1 shows a sheet of card. Figure 1 Describe how to find the centre of mass of this sheet of card. You may draw diagrams as part of your answer. ........................................................................................................................ ........................................................................................................................ ........................................................................................................................ ........................................................................................................................ ........................................................................................................................ ........................................................................................................................ ........................................................................................................................ ........................................................................................................................ ........................................................................................................................ ........................................................................................................................ ........................................................................................................................ ....................................................................................................................... -

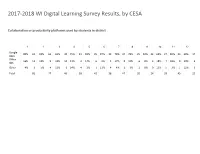

2017-2018 WI Digital Learning Survey Results, by CESA

2017-2018 WI Digital Learning Survey Results, by CESA Collaboration or productivity platforms used by students in district 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Google 80% 65 83% 64 65% 30 75% 21 83% 35 87% 33 79% 37 78% 25 92% 22 69% 27 80% 36 68% 17 Apps Office 16% 13 12% 9 22% 10 11% 3 14% 6 3% 1 17% 8 19% 6 8% 2 18% 7 18% 8 20% 5 365 Other 4% 3 5% 4 13% 6 14% 4 2% 1 11% 4 4% 2 3% 1 0% 0 13% 5 2% 1 12% 3 Total 81 77 46 28 42 38 47 32 24 39 45 25 Grade levels where most or all social media sites are blocked 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 K 9% 48 9% 54 8% 28 8% 17 9% 30 9% 29 8% 34 8% 26 9% 17 8% 22 8% 29 7% 11 1 9% 47 9% 54 8% 28 8% 17 9% 30 9% 29 8% 34 8% 26 9% 17 8% 22 8% 29 7% 11 2 9% 47 9% 54 8% 28 8% 17 9% 30 9% 29 8% 34 8% 26 9% 17 8% 22 8% 29 7% 11 3 9% 47 9% 54 8% 27 8% 17 8% 28 9% 29 8% 33 8% 26 9% 17 8% 22 8% 29 7% 11 4 9% 47 9% 54 8% 27 8% 17 8% 28 9% 29 8% 33 8% 26 9% 16 8% 22 8% 29 7% 11 5 9% 46 9% 53 8% 27 7% 16 8% 27 9% 29 8% 32 8% 26 9% 16 8% 21 8% 27 7% 11 6 8% 44 9% 51 8% 26 8% 17 7% 25 8% 28 8% 33 8% 24 8% 15 7% 20 8% 27 7% 11 7 8% 43 9% 51 8% 26 8% 17 7% 25 8% 27 8% 33 7% 23 7% 13 7% 19 8% 27 7% 11 8 8% 44 9% 50 8% 26 8% 17 7% 25 8% 27 8% 32 7% 23 7% 12 7% 19 8% 27 7% 11 9 5% 26 4% 25 7% 24 8% 17 7% 23 6% 20 7% 27 7% 23 5% 10 7% 18 6% 23 7% 11 10 5% 26 4% 25 7% 24 8% 17 6% 22 6% 20 7% 27 7% 23 5% 10 7% 18 6% 23 7% 11 11 5% 26 4% 24 7% 24 8% 17 6% 22 6% 20 7% 27 7% 23 5% 10 7% 18 6% 23 7% 11 12 5% 26 4% 24 7% 23 8% 17 6% 22 6% 20 7% 27 7% 23 5% 10 7% 18 6% 23 7% 11 None 2% 13 2% 9 1% 3 1% 3 1% 5 1% 3 0% 2 0% 0 2% 4 3% 7 3% 9 3% 5 -

Ocln 530 Radioeins Datum: 25.07.2009 Oceanclub Latenite 530 1:00 Bis 05:00 Gudrun Gut Redaktion: G.Gut + Thomas Fehlmann

ocln 530 radioeins Datum: 25.07.2009 oceanclub LateNite 530 1:00 bis 05:00 gudrun gut Redaktion: g.gut + thomas fehlmann TITEL* INTERPRET* ALBUM BEMERKUNGEN NACHRICHTEN a www.radioeins.de OCEANCLUB JINGLE Begin www.oceanclub.de everytime SKIT j. dilla yancey boys instrumentals www.myspace.com/jdilla the last and least likely ribbons royals www.osaka.ie fools the dodos visiter www.dodosmusic.net take off my shirt vincent it's only wasteland, mum! www.blankrecords.de the walk (poponame mix) andreas heiszenberger ep www.polytone-music.com OCEANCLUB JINGLE www.oceanclub.de hard boiled babe lizzy mercier descloux va: ze 30 - ze records 1979-2009 www.zerecords.com jukebox babe alan vega va: ze 30 - ze records 1979-2009 www.zerecords.com drops of color green sky accident drops of color www.interregnumrecords.com butterfly envy delicate noise filmezza www.lensrecords.com OCEANCLUB JINGLE www.oceanclub.de the bone song the sa-ra creative partners nuclear revolution - the age of love www.ubiquityrecords.com eid ma clack shaw bill callahan sometimes i wish we were an eagle www.dragcity.com roll on babe vetiver things of the past www.fat-cat.co.uk not leaving town patrick kelleher you look cold www.osaka.ie teen diethylamide25 the rational academy swans www.someonegood.org 12 feet in cheltenham the rational academy swans www.someonegood.org NACHRICHTEN b www.radioeins.de CIO D'OR OC MIX www.ciodor.de starlight - intrusion dub model 500 va: CIO D'OR mix www.ciodor.de cv313 reduction 2- vantage isle deepchord va: CIO D'OR mix www.ciodor.de reduction echospace va: CIO D'OR mix www.ciodor.de dc mix3 - vantage isle deepchord va: CIO D'OR mix www.ciodor.de zap - norman nodge mix (coming homeandre ep) lodemann va: CIO D'OR mix www.ciodor.de rever.. -

Oc Late Nite 540 XMAS

oc late nite 540 XMAS radioeins 26.12.2009 Startzeit: 01:00:00 oceanclub LateNite 540 xmess Endzeit: 05:00:00 gudrun gut g.gut + thomas fehlmann Kostentr: rbb TITEL* INTERPRET* ALBUM BEMERKUNGEN NACHRICHTEN a www.radioeins.de OCEANCLUB JINGLE Begin www.oceanclub.de everytime SKIT j. dilla yancey boys instrumentals www.myspace.com/jdilla ofterschwang jürgen paape va: kompakt total 10 www.kompakt.fm gettin down for xmas milly + silly va: in the christmas groove www.strut-records.com midtown 120 blues dj sprinkles midtown 120 blues ep www.mulemusiq.com Eid Ma Clack Shaw bill callahan Sometimes I Wish We Were An Eagle www.dragcity.com OCEANCLUB JINGLE www.oceanclub.de fikratchin (w. menelik wossenatchew) mulatu astatke www.strut-records.com zither + horn wolfgang voigt va: pop ambient 2010 www.kompakt.fm my girls animal collective merriweather post pavillon animalcollective.org under palm trees mo'jo white ep www.whitelovesyou.com OCEANCLUB JINGLE www.oceanclub.de the new year jimmy jules va: in the christmas groove www.strut-records.com recomposed... moritz von oswald remix recomposed by carl craig + moritz von oswaldwww.klassikakzente.de/carlcraig rmx10" NACHRICHTEN b www.radioeins.de OCEANCLUB JINGLE www.oceanclub.de lil girl (f. fatima) shafiq en'a free ka www.rapsterrecords.com everybody's got to learn sometime the field yesterday and today www.kompakt.fm kiss my name anthony and the johnsons the crying light www.antonyandthejohnsons.com ital gala drop gala drop www.myspace.com/galadrop OCEANCLUB JINGLE www.oceanclub.de bodenweich dj koze va: pop ambient 2010 www.kompakt.fm moments in life andres momants in life ep www.mahoganimusic.com two weeks grizzly bear veckatimest www.grizzly-bear.net marauder kreidler mosaik 2014 www.italic.de ttv telefon tel aviv fahrenheit fair enough www.hefty.com OCEANCLUB JINGLE www.oceanclub.de auld lang syne the black on white affair va: in the christmas groove www.strut-records.com auditorium w.