New York State Offshore Wind Master Plan: Cultural Resources Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Side Scan Sonar and the Management of Underwater Cultural Heritage Timmy Gambin

259 CHAPTER 15 View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OAR@UM Side Scan Sonar and the Management of Underwater Cultural Heritage Timmy Gambin Introduction Th is chapter deals with side scan sonar, not because I believe it is superior to other available technologies but rather because it is the tool that I have used in the context of a number of off shore surveys. It is therefore opportune to share an approach that I have developed and utilised in a number of projects around the Mediterranean. Th ese projects were conceptualised together with local partners that had a wealth of local experience in the countries of operation. Over time it became clear that before starting to plan a project it is always important to ask oneself the obvious question – but one that is oft en overlooked: “what is it that we are setting out to achieve”? All too oft en, researchers and scientists approach a potential research project with blinkers. Such an approach may prove to be a hindrance to cross-fertilisation of ideas as well as to inter-disciplinary cooperation. Th erefore, the aforementioned question should be followed up by a second query: “and who else can benefi t from this project?” Benefi ciaries may vary from individual researchers of the same fi eld such as archaeologists interested in other more clearly defi ned historic periods (World War II, Early Modern shipping etc) to other researchers who may be interested in specifi c studies (African amphora production for example). -

AMERICAN YACHTING ;-Rhg?>Y^O

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2007 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/americanyachtingOOsteprich THE AMERICAN SPORTSMAN'S LIBRARY EDITED BY CASPAR WHITNEY AMERICAN YACHTING ;-rhg?>y^o AMERICAN YACHTING BY W. p. STEPHENS Of TH£ UNfVERSITY Of NelD gork THE MACMILLAN COMPANY LONDON: MACMILLAN & CO., Ltd. 1904 All rights reserved Copyright, 1904, By the MACMILLAN COMPANY. Set up, electrotyped, and published April, 1904. Norwood Press Smith Co, J. S. Gushing & Co. — Berwick & Norwood^ Mass.f U.S.A. INTRODUCTION In spite of the utilitarian tendencies of the present age, it is fortunately no longer necessary to argue in behalf of sport; even the busiest of busy Americans have at last learned the neces- sity for a certain amount of relaxation and rec- reation, and that the best way to these lies in the pursuit of some form of outdoor sport. While each has its stanch adherents, who pro- claim its superiority to all others, the sport of yachting can perhaps show as much to its credit as any. As a means to perfect physical development, one great point in all sports, it has the advantage of being followed outdoors in the bracing atmos- phere of the sea; and while it involves severe physical labor and at times actual hardships, it fits its devotees to withstand and enjoy both. In the matter of competition, the salt and savor of all sport, yachting opens a wide and varied field. In cruising there is a constant strife 219316 vi Introduction with the elements, and in racing there is the contest of brain and hand against those of equal adversaries. -

Fire Island Light Station

Form No. 10-306 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM FOR FEDERAL PROPERTIES SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES--COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Fire Island Light Station _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN Bay Shore 0.1. STATE CODE COUNTY CODE New York 36 Suffolk HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _ DISTRICT -XPUBLIC OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM _ BUILDING(S) ^.PRIVATE X.UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL XPARK _XSTRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _ IN PROCESS iLYES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED —YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: AGENCY REGIONAL HEADQUARTERS: (If applicable) National Park Service, Morth Atlantic Region STREET & NUMBER 15 State Street CITY. TOWN STATE VICINITY OF Massachusetts COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDSETC. Land Acquisition Division, National Park Service, North Atlantic CITY. TOWN STATE Boston, Massachusetts TITLE U.S. Coast Guard, 3d Dist., "Fire Island Station Annex" Civil Plot Plan 03-5523 DATE 18 June 1975, revised 8-7-80 .^FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS- Nationa-| park Service, North Atlantic Regional Office CITY, TOWN CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT _DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X-ORIGINAL SITE —GOOD _RUINS . X-ALTERED —MOVED DATE_____ X.FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Fire Island Light Station is situated 5 miles east of the western end of Fire Island, a barrier island off the southern coast of Long Island. It consists of a lighthouse and an adjacent keeper's quarters sitting on a raised terrace. -

IMCA D033 Limitations in the Use of Scuba Offshore

AB The International Marine Contractors Association Limitations in the Use of SCUBA Offshore IMCA D 033 www.imca-int.com October 2003 AB The International Marine Contractors Association (IMCA) is the international trade association representing offshore, marine and underwater engineering companies. IMCA promotes improvements in quality, health, safety, environmental and technical standards through the publication of information notes, codes of practice and by other appropriate means. Members are self-regulating through the adoption of IMCA guidelines as appropriate. They commit to act as responsible members by following relevant guidelines and being willing to be audited against compliance with them by their clients. There are two core committees that relate to all members: Safety, Environment & Legislation Training, Certification & Personnel Competence The Association is organised through four distinct divisions, each covering a specific area of members’ interests: Diving, Marine, Offshore Survey, Remote Systems & ROV. There are also four regional sections which facilitate work on issues affecting members in their local geographic area – Americas Deepwater, Asia-Pacific, Europe & Africa and Middle East & India. IMCA D 033 This guidance document was prepared for IMCA under the direction of its Diving Division Management Committee, enhancing and extending guidance formerly available via guidance note AODC 065, which is now withdrawn. www.imca-int.com/diving The information contained herein is given for guidance only and endeavours to reflect best industry practice. For the avoidance of doubt no legal liability shall attach to any guidance and/or recommendation and/or statement herein contained. Limitations in the Use of SCUBA Offshore 1 BACKGROUND SCUBA – self-contained underwater breathing apparatus – was first developed in the 1940s and has since become widely used for recreational and amateur diving. -

National Conference on Mass. Transit Crime and Vandali.Sm Compendium of Proceedings

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. n co--~P7 National Conference on Mass. Transit Crime and Vandali.sm Compendium of Proceedings Conducted by T~he New York State Senate Committee on Transportation October 20-24, 1980 rtment SENATOR JOHN D. CAEMMERER, CHAIRMAN )ortation Honorable MacNeil Mitchell, Project Director i/lass )rtation ~tration ansportation ~t The National Conference on Mass Transit Crime and Vandalism and the publication of this Compendium of the Proceedings of the Conference were made possible by a grant from the United States Department of Transportation, Urban Mass Transportation Administration, Office of Transportation Management. Grateful acknowledgement is extended to Dr. Brian J. Cudahy and Mr. Marvin Futrell of that agency for their constructive services with respect to the funding of this grant. Gratitude is extended to the New York State Senate for assistance provided through the cooperation of the Honorable Warren M. Anderson, Senate Majority Leader; Dr. Roger C. Thompson, Secretary of the Senate; Dr. Stephen F. Sloan, Director of the Senate Research Service. Also our appreciation goes to Dr. Leonard M. Cutler, Senate Grants Officer and Liaison to the Steering Committee. Acknowledgement is made to the members of the Steering Committee and the Reso- lutions Committee, whose diligent efforts and assistance were most instrumental in making the Conference a success. Particular thanks and appreciation goes to Bert'J. Cunningham, Director of Public Affairs for the Senate Committee on Transportation, for his work in publicizing the Conference and preparing the photographic pages included in the Compendium. Special appreciation for the preparation of this document is extended to the Program Coordinators for the Conference, Carey S. -

Information Synthesis on the Potential for Bat Interactions with Offshore Wind Facilities

_______________ OCS Study BOEM 2013-01163 Information Synthesis on the Potential for Bat Interactions with Offshore Wind Facilities Final Report U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Ocean Energy Management Office of Renewable Energy Programs www.boem.gov OCS Study BOEM 2013-01163 Information Synthesis on the Potential for Bat Interactions with Offshore Wind Facilities Final Report Authors Steven K. Pelletier Kristian S. Omland Kristen S. Watrous Trevor S. Peterson Prepared under BOEM Contract M11PD00212 by Stantec Consulting Services Inc. 30 Park Drive Topsham, ME 04086 Published by U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Ocean Energy Management Herndon, VA Office of Renewable Energy Programs June 2013 DISCLAIMER This report was prepared under contract between the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) and Stantec Consulting Services Inc. This report has been technically reviewed by BOEM, and it has been approved for publication. Approval does not signify that the contents necessarily reflect the views and policies of BOEM, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation for use. It is, however, exempt from review and compliance with BOEM editorial standards. REPORT AVAILABILITY The report may be downloaded from the boem.gov website through the Environmental Studies Program Information System (ESPIS). You will be able to obtain this report from BOEM or the National Technical Information Service. U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Department of Commerce Bureau of Ocean Energy Management National Technical Information Service Office of Renewable Energy Programs 5285 Port Royal Road 381 Elden Street, HM-1328 Springfield, Virginia 22161 Herndon, VA 20170 Phone: (703) 605-6040 Fax: (703) 605-6900 Email: [email protected] CITATION Pelletier, S.K., K. -

Overview of Geophysical and Geotechnical Marine Surveys for Offshore Wind Transmission Cables in the UK September 2015

Overview of geophysical and geotechnical marine surveys for offshore wind transmission cables in the UK September 2015 Overview of geophysical and geotechnical marine surveys for offshore wind transmission cables in the UK Disclaimer Whilst the information contained in this report has been prepared and collated in good faith, the Offshore Wind Programme Board (OWPB) makes no representation or warranty (express or implied) as to the accuracy or completeness of the information contained in this report (including any enclosures and attachments) nor shall be liable for any loss or damage, whether direct or consequential, arising from reliance on this report by any person. In particular, but without limitation, the OWPB accepts no responsibility for accuracy and completeness for any comments on, or opinions regarding the functional and technical capabilities of any software, equipment or other products mentioned in the report. The OWPB is not responsible in any way in connection with erroneous information or data contained or referred to in this document. It is up to those who use the information in this report to satisfy themselves as to its accuracy. This report and its contents do not constitute professional advice. Specific advice should be sought about your specific circumstances. The information contained in this report has been produced by a working group of industry professionals and has not been subject to independent verification. The OWPB has not sought to independently corroborate this information. The OWPB accepts no responsibility for accuracy and completeness for any comments on, or opinions regarding the functional and technical capabilities of any software, equipment or other products mentioned. -

Epilogue 1941—Present by BARBARA LA ROCCO

Epilogue 1941—Present By BARBARA LA ROCCO ABOUT A WEEK before A Maritime History of New York was re- leased the United States entered the Second World War. Between Pearl Harbor and VJ-Day, more than three million troops and over 63 million tons of supplies and materials shipped overseas through the Port. The Port of New York, really eleven ports in one, boasted a devel- oped shoreline of over 650 miles comprising the waterfronts of five boroughs of New York City and seven cities on the New Jersey side. The Port included 600 individual ship anchorages, some 1,800 docks, piers, and wharves of every conceivable size which gave access to over a thousand warehouses, and a complex system of car floats, lighters, rail and bridge networks. Over 575 tugboats worked the Port waters. Port operations employed some 25,000 longshoremen and an additional 400,000 other workers.* Ships of every conceivable type were needed for troop transport and supply carriers. On June 6, 1941, the U.S. Coast Guard seized 84 vessels of foreign registry in American ports under the Ship Requisition Act. To meet the demand for ships large numbers of mass-produced freight- ers and transports, called Liberty ships were constructed by a civilian workforce using pre-fabricated parts and the relatively new technique of welding. The Liberty ship, adapted by New York naval architects Gibbs & Cox from an old British tramp ship, was the largest civilian- 262 EPILOGUE 1941 - PRESENT 263 made war ship. The assembly-line production methods were later used to build 400 Victory ships (VC2)—the Liberty ship’s successor. -

Of the New Jersey Maritime Pi- Lot and Docking Pilot Commission

156th Annual Report Of The New Jersey Maritime Pi- lot and Docking Pilot Commission Dear Governor and Members of the New Jersey Legislature, In 1789, the First Congress of the United States delegated to the states the authority to regulate pilotage of vessels operating on their respective navigable waters. In 1837, New Jersey enacted legislation establishing the Board of Commissioners of Pilotage of the State of New Jersey. Since its creation the Commission has had the responsibility of licensing and regulating maritime pilots who direct the navigation of ships as they enter and depart the Port of New Jersey and New York. This oversight has contributed to the excellent reputation the ports of New Jersey and New York has and its pilots enjoy throughout the maritime world. New legislation that went into effect on September 1, 2004 enables the Commission to further contribute to the safety and security of the port by requiring the Commission to license docking pilots. These pilots specialize in the docking and undocking of vessels in the port. To reflect the expansion of its jurisdiction the Commission has been renamed “The New Jersey Maritime Pilot and Docking Pilot Commission.” In keeping with the needs of the times, the new legislation has a strong security component. All pilots licensed by the state will go through an on going security vetting. The Commission will issue badges and photo ID cards to all qualified pilots, which they must display when entering port facilities and boarding vessels. The legislation has also modernized and clarified the Commissions’ authority to issue regulations with respect to qualifications and training required for pilot licenses, pilot training (both initial and recurrent) accident investigation and drug and alcohol testing. -

Norway/UK Regulatory Guidance for Offshore Diving

AB The International Marine Contractors Association Norway/UK Regulatory Guidance for Offshore Diving (NURGOD) IMCA D 034 www.imca-int.com December 2003 AB The International Marine Contractors Association (IMCA) is the international trade association representing offshore, marine and underwater engineering companies. IMCA promotes improvements in quality, health, safety, environmental and technical standards through the publication of information notes, codes of practice and by other appropriate means. Members are self-regulating through the adoption of IMCA guidelines as appropriate. They commit to act as responsible members by following relevant guidelines and being willing to be audited against compliance with them by their clients. There are two core activities that relate to all members: Safety, Environment & Legislation Training, Certification & Personnel Competence The Association is organised through four distinct divisions, each covering a specific area of members’ interests: Diving, Marine, Offshore Survey, Remote Systems & ROV. There are also four regional sections which facilitate work on issues affecting members in their local geographic area – Americas Deepwater, Asia-Pacific, Europe & Africa and Middle East & India. IMCA D 034 The Norway/UK Regulatory Guidance for Offshore Diving (NURGOD) has been developed jointly by IMCA, under the direction of its Diving Division Management Committee, and OLF (Oljeindustriens Landsforening – The Norwegian Oil Industry Association). www.imca-int.com/diving The information contained herein is given for guidance only and endeavours to reflect best industry practice. For the avoidance of doubt no legal liability shall attach to any guidance and/or recommendation and/or statement herein contained. Norway/UK Regulatory Guidance for Offshore Diving IMCA D 034 – December 2003 1 Introduction and Scope................................................................................................... -

List of United States Air Force Aircraft Control and Warning Squadrons from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

List of United States Air Force aircraft control and warning squadrons From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Contents [hide ] • 1 Content • 2 Site codes o 2.1 Sites Within the United States o 2.2 Sites Outside the United States • 3 Squadrons • 4 See also • 5 References • 6 External links Content [edit ] The List of United States Air Force Aircraft Control and Warning Squadrons identifies Squadron Emblem or patch Location, Air Force Station (AFS), or Air Station (AS) North American Air Defense Command (NORAD) code or other identification code for the location Any pertinent notes, including dates active and other designations. Site codes [edit ] Sites Within the United States [edit ] • DC-xx Semi-Automatic Ground Environment (SAGE) Direction Center/Combat Center. • F-xx Alaskan air defense sites. • H-0x Hawaiian air defense sites. • L-xx Original Air Defense Command (ADC) 1946 "Lashup" Radar Network of temporary sites to provide detection at designated important locations using radar sets left over from World War II . • LP-xx "Lashup" site which was incorporated into the first ADC permanent radar network in 1949. • P-xx Original 75 permanent stations established in 1949. • RP-xx Sites that replaced a permanent 1949 station. • M-xx 1952 Phase I Mobile Radar station. • SM-xx 1955 Phase II Mobile Radar Station. • TM-xx 1959 Phase III Mobile station. • TT-x Texas Towers , radar tower rigs off the East Coast of the United States, named because of their resemblance to oil drilling rigs in the Gulf of Mexico. • Z-xx NORAD designation for sites after 31 July 1963. P, M, SM, and TM stations active after that date retained their numbers, but were designated "Z-xx". -

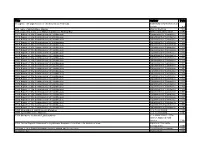

Lighthouse Bibliography.Pdf

Title Author Date 10 Lights: The Lighthouses of the Keweenaw Peninsula Keweenaw County Historical Society n.d. 100 Years of British Glass Making Chance Brothers 1924 137 Steps: The Story of St Mary's Lighthouse Whitley Bay North Tyneside Council 1999 1911 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1911 1912 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1912 1913 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1913 1914 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1914 1915 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1915 1916 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1916 1917 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1917 1918 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1918 1919 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1919 1920 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1920 1921 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1921 1922 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1922 1923 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1923 1924 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1924 1925 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1925 1926 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1926 1927 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1927 1928 Report of the Commissioner of