Epilogue 1941—Present by BARBARA LA ROCCO

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Managing the Retreat from Rising Seas

Managing the Retreat from Rising Seas Staten Island, New York: Oakwood Beach Buyout Committee and Program Matthew D. Viggiano, formerly New York City Cover Photo Credits: Authors Mayor’s Office of Housing Recovery Operations, (top row, left to right): This report was written by Katie Spidalieri, Senior New York; Andrew Meyer, San Diego Audubon, Watershed Protection Department, City of Austin, Associate, and Isabelle Smith, Research Assistant, California; Tim Trautman, Charlotte-Mecklenburg Texas; U.S. Fish and Wildlife Georgetown Climate Center at Georgetown Uni- Storm Water Services, North Carolina; Pam Service; U.S. Fish and versity Law Center; and Jessica Grannis, Coastal Kearfott, City of Austin Watershed Protection Wildlife Service; Integration Resilience Director at National Audubon Society. Department, Texas; James Wade, Harris County and Application Network, University of Maryland The Louisiana Strategic Adaptations for Future Flood Control District, Texas; Fawn McGee, New Center for Environmental Environments (LA SAFE) case study was written by Jersey Department of Environmental Protection; Science. Jennifer Li, Staff Attorney, and Alex Love, student, Frances Ianacone, New Jersey Department of (center row, left to right): Harrison Institute for Public Law at Georgetown Environmental Protection; Thomas Snow, Jr., State of Louisiana Office of University Law Center. Editorial and writing support New York State Department of Environmental Community Development; Integration and Application were provided by Vicki Arroyo, Executive Director, Conservation; Dave Tobias, New York City Network, University of and Lisa Anne Hamilton, Adaptation Program Direc- Department of Environmental Protection, Maryland Center for tor, Georgetown Climate Center. New York; Stacy Curry, Office of Emergency Environmental Science; Will Parson, Chesapeake Management, Woodbridge Township, New Bay Program, U.S. -

4/8/69 #778 Miss Harlem Beauty Contest Applications Available #779 19Th Annual Valentines Day Winter Ca

W PRESSRELEASES 2/7/69 - 4/8/69 #778 Miss Harlem Beauty Contest Applications Available #779 19th Annual Valentines Day Winter Carnival In Queens (Postponed Until Friday, February 21, 1969) #780 Police Public Stable Complex, 86th St., Transverse, Central Park #781 Monday, March 10th, Opening Date For Sale of Season Golf Lockers and Tennis Permits #782 Parks Cited For Excellence of Design #783 New York City's Trees Badly Damaged During Storm #784 Lifeguard Positions Still Available #785 Favored Knick To Be Picked #786 Heckschers Cutbacks In State Aid to the City #787 Young Chess Players to Compete #788 r Birth of Lion and Lamb #789 Jones Gives Citations at Half Time (Basketball) #790 Nanas dismantled on March 27, 1969 #791 Birth of Aoudad in Central Park Zoo #792 Circus Animals to Stroll in Park #793 Richmond Parkway Statement #794 City Golf Courses, Lawn Bowling and Croquet Cacilities Open #795 Eggs-Egg Rolling - Several Parks #796 Fifth Annual Golden Age Art Exhibition #797 Student Sculpture Exhibit In Central Park #798 Charley the Mule Born March 27 in Central Park Zoo #799 Rain date for Easter Egg Rolling contest April 12, original date above #800 Sculpture - Central Park - April 10 2 TOTAL ESTIMATED ^DHSTRUCTION COST: $5.1 Million DESCRIPTION: Most of the facilities will be underground. Ground-level rooftops will be planted as garden slopes. The stables will be covered by a tree orchard. There will be panes of glass in long shelters above ground so visitors can watch the training and stabling of horses in the underground facilities. Corrals, mounting areas and exercise yards, for both public and private use, will be below grade but roofless and open for public observation. -

2008 Inventory Location Maps

2008 INVENTORY LOCATION MAPS Eight years ago, we added a new feature to the Inventory Location Maps; Community Board borders. With this added feature, the reader will be able to identify within which Community Boards bridges are located. On these maps, all Community Boards consist of three (3) digits. The first digit is for map plotting purposes. The next two digits identify the Community Board. In cases of certain parks and airports, the Community Board number does not correspond with any Community Board. These exceptions are: Bronx 26=Van Cortlandt Park Brooklyn 55=Prospect Park 27=Bronx Park 56=Gateway Nat’l Rec. Area/Floyd Bennett Field 28=Pelham Bay Park Queens 80=La Guardia Airport Manhattan 64= Central Park 81=Alley Pond Park 82=Cunningham Park 83=JFK Airport 84= Gateway Nat’l Rec. Area/Fort Tilden-Jacob Riis Park The Community Board listings correspond to those listed in the inventory, which begins on page 209. Some structures fall on Community Board dividing lines: their additional Community Boards are now identified in the inventory in columns CD2 and CD3. Brooklyn, Manhattan, and Williamsburg Bridges. (Credit: Michele N. Vulcan) 313 2008 BRIDGES AND TUNNELS ANNUAL CONDITION REPORT ALL BOROUGHS Bronx Manhattan Queens Brooklyn Staten Island Legend BOROUGHS Central Park Brooklyn Manhattan Queens Staten Island 0 8,000 16,000 32,000 48,000 64,000 The Bronx Feet Scale BROOKLYN Pulaski Bridge 2240639 KOSCIUSZKO Williamsburg MANHATTAN BRIDGE AVENUE 2240370 Manhattan Bridge Bridge BQE See Brooklyn 2240027 2240028 301 2240390 CB 302, -

Staten Island

Staten Island Waterfront History By Carlotta DeFillo taten Island has 35 miles of waterfront. It is bordered by Newark Bay and the Kill van Kull on the north, Upper New York Bay, the Narrows, S Lower New York Bay and the Atlantic Ocean on the east, Raritan Bay on the south and the Arthur Kill or Staten Island Sound on the west. Several smaller islands sit offshore. Shooters Island near Mariners Harbor was home to Standard Shipbuilding Corp. and Prall’s Island is a bird sanctuary. Off South Beach lie the man-made Hoffman and Swinburne Islands. These two islands were built for use as the quarantine station in 1872, and abandoned in 1933. During World War II they were used for military training, only to be aban- doned again at war’s end. The earliest inhabitants of Staten Island were Algonkian-speaking Native Americans who set up camps along the shores in the areas of Tottenville, Prince’s Bay, Great Kills, Arrochar, Stapleton, West New Brighton, Mariners Harbor and Fresh Kills. They harvested berries, fi sh, oysters and clams, and even ran the Island’s earliest ferries. The fi rst Europeans set foot on Staten Island in Tompkinsville at the Watering Place, a spring of fresh water near the shore, before 1623. The earliest public ferry was in operation in Stapleton by 1708, and by the 1770s ten ferry lines connected Staten Island to New Jersey, Manhattan and Brooklyn. The best-known Island ferryman was Cornelius Vanderbilt, who started an empire from his single sailboat ferry, starting in 1810. -

Rising from Ground Zero from the EDITOR There Are No Words, Even Images, That Can Fully Capture the EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Devastation of September 11, 2001

GROUNDRISING ZERO: FROM REFLECTIONS ON 9/11 IN NYC, 20 YEARS LATER Sponsored by 1 Rising from Ground Zero FROM THE EDITOR There are no words, even images, that can fully capture the EDITOR-IN-CHIEF devastation of September 11, 2001. Janelle Foskett [email protected] For those of us who were not on the scene that day, we can only imagine what it must have been like for first responders EXECUTIVE EDITOR to face 16 acres of horror at Ground Zero, to see a symbol of Marc Bashoor America’s military on fire, and to descend upon a Pennsylvania [email protected] field covered in pieces of an airliner. Those who did face these unimaginable scenes have graciously shared their unique SR. ASSOCIATE EDITOR insights – an inside look at how incident command unfolded at Rachel Engel the scene, the immediate work to support FDNY, and how the [email protected] tragedy changed the survivors forever. It is through their eyes that we reflect on the 20th anniversary of September 11, 2001. EDITORIAL DIRECTOR Greg Friese This publication focuses on personal reflections from the New [email protected] York City response; additional special coverage of response efforts to the Pentagon and Shanksville, Pa., can be found at VP OF CONTENT firerescue1.com/Sept11-20years. Jon Hughes [email protected] We remember and honor the lives lost at the Pentagon, aboard Flight 93 and in New York City, including the 343 firefighters GRAPHIC DESIGN killed on 9/11 and the hundreds who have since lost their lives to Ariel Shumar WTC-related illness. -

Request for Proposals Passenger Ferry Operator

PBHFS – RFP 2018 REQUEST FOR PROPOSALS PASSENGER FERRY OPERATOR For the PENINSULA AT BAYONNE HARBOR BAYONNE, NEW JERSEY JUNE 12, 2018 1 PBHFS – RFP 2018 I. INTRODUCTION AND GENERAL INFORMATION WELCOME TO THE CITY OF BAYONNE AND THE PENINSULA AT BAYONNE HARBOR: Bayonne’s shipping port terminal on New York Bay, built in 1932 to create additional industrial space for the city, was taken over by the U.S. Navy during World War II and the U.S. Army in 1967. Ships carried goods from the terminal for every major U.S. military operation from World War II to the Persian Gulf and Haiti missions in the 1990s. At its peak, the Military Ocean Terminal at Bayonne (MOTBY) employed 3,000 civilian and armed services personnel – many of whom lived in the area – and handled more than 1 million tons of cargo each year. But with the end of the Cold War and the subsequent decreasing need for the deployment of U.S. forces, the federal government decided to close MOTBY down in 1995, despite strong opposition from state and local officials. Jobs were phased out over the next three years; the closure was complete in 1999. But the value of this former naval supply center was obvious to some. In 2002, MOTBY was officially renamed The Peninsula at Bayonne Harbor by the Bayonne Local Redevelopment Authority (BLRA) – the city’s redevelopment arm. Plans were unveiled to redevelop the 430-acre former ocean terminal into a mixed-use complex. The project began in 2002, environmental cleanup was completed, building were demolished and construction began. -

Firefighter Informational Tutorial

The careerof a lifetime starts here. Carlos F. Munroe Sarina Olmo AnitaDaniel Danny Chan Brooke Guinan AndrewM. Brown Battalion 35 Ladder29 Engine234 Ladder109 Engine312 Ladder176 FIREFIGHTER INFORMATIONAL TUTORIAL [PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK] Daniel A. Nigro Fire Commissioner July 5, 2017 Dear Applicants, This test preparation guide has been assembled to help prepare you for the upcoming New York City Firefighter exam, and was developed to complement the online tutorial that you'll find on the DCAS website (nyc.gov). This booklet will provide you with valuable test and note-taking tips, along with sample math and reading comprehension exercises. In addition, the new exam format includes video exercises which will help applicants judge how well they are taking notes, retaining information and answering questions. I want to thank the FDNY Recruitment & Retention team for preparing this booklet. I also want to thank each applicant for attending these sessions and taking advantage of the opportunity to learn as much as you can about the test. I began my career as a Firefighter in 1969, rising through all of the ranks, and now, as Fire Commissioner, I can tell you there is no better job in the world than being one of New York City's Bravest. I, therefore, encourage you to study and work hard in preparation for the upcoming test. I wish each and every one of you good luck on the test! Daniel A. Nigro Fire Commissioner DAN/yk Fire Department, City of New York 9 MetroTech Center Brooklyn New York 11201-3857 TABLE OF CONTENTS SUGGESTED READING COMPREHENSION TIPS ....................................................................................................... -

Aroundmanhattan

Trump SoHo Hotel South Cove Statue of Liberty 3rd Avenue Peter J. Sharp Boat House Riverbank State Park Chelsea Piers One Madison Park Four Freedoms Park Eastwood Time Warner Center Butler Rogers Baskett Handel Architects and Mary Miss, Stanton Eckstut, F A Bartholdi, Richard M Hunt, 8 Spruce Street Rotation Bridge Robert A.M. Stern & Dattner Architects and 1 14 27 40 53 66 Cetra Ruddy 79 Louis Kahn 92 Sert, Jackson, & Assocs. 105 118 131 144 Skidmore, Owings & Merrill Marner Architecture Rockwell Group Susan Child Gustave Eiffel Frank Gehry Thomas C. Clark Armand LeGardeur Abel Bainnson Butz 23 East 22nd Street Roosevelt Island 510 Main St. Columbus Circle Warren & Wetmore 246 Spring Street Battery Park City Liberty Island 135th St Bronx to E 129th 555 W 218th Street Hudson River -137th to 145 Sts 100 Eleventh Avenue Zucotti Park/ Battery Park & East River Waterfront Queens West / NY Presbyterian Hospital Gould Memorial Library & IRT Powerhouse (Con Ed) Travelers Group Waterside 2009 Addition: Pei Cobb Freed Park Avenue Bridge West Harlem Piers Park Jean Nouvel with Occupy Wall St Castle Clinton SHoP Architects, Ken Smith Hunters Point South Hall of Fame McKim Mead & White 2 15 Kohn Pedersen Fox 28 41 54 67 Davis, Brody & Assocs. 80 93 and Ballinger 106 Albert Pancoast Boiler 119 132 Barbara Wilks, Archipelago 145 Beyer Blinder Belle Cooper, Robertson & Partners Battery Park Battery Maritime Building to Pelli, Arquitectonica, SHoP, McKim, Mead, & White W 58th - 59th St 388 Greenwich Street FDR Drive between East 25th & 525 E. 68th Street connects Bronx to Park Ave W127th St & the Hudson River 100 11th Avenue Rutgers Slip 30th Streets Gantry Plaza Park Bronx Community College on Eleventh Avenue IAC Headquarters Holland Tunnel World Trade Center Site Whitehall Building Hospital for Riverbend Houses Brooklyn Bridge Park Citicorp Building Queens River House Kingsbridge Veterans Grant’s Tomb Hearst Tower Frank Gehry, Adamson Ventilation Towers Daniel Libeskind, Norman Foster, Henry Hardenbergh and Special Surgery Davis, Brody & Assocs. -

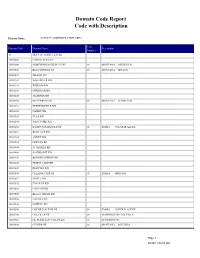

Domain Code Report Code with Description

Domain Code Report Code with Description Element Name: AGENCY ADMINISTRATIVE AREA Line Domain Code Domain Name Description Number 10 DEPT OF AGRICULTURE 10000000 FOREST SERVICE 10010000 NORTHERN REGION USFS 01 MONTANA MISSOULA 10010200 BEAVERHEAD NF 01 MONTANA DILLON 10010201 DILLON RD 10010202 WISE RIVER RD 10010203 WISDOM RD 10010206 SHERIDAN RD 10010207 MADISON RD 10010300 BITTERROOT NF 01 MONTANA HAMILTON 10010301 STEVENSVILLE RD 10010302 DARBY RD 10010303 SULA RD 10010304 WEST FORK RD 10010400 IDAHO PANHANDLE NF 01 IDAHO COEUR D ALENE 10010401 WALLACE RD 10010402 AVERY RD 10010403 FERNAN RD 10010404 ST MARIES RD 10010406 SANDPOINT RD 10010407 BONNERS FERRY RD 10010408 PRIEST LAKE RD 10010409 RED IVES RD 10010500 CLEARWATER NF 01 IDAHO OROFINO 10010501 PIERCE RD 10010502 PALOUSE RD 10010503 CANYON RD 10010504 KELLY CREEK RD 10010505 LOCHSA RD 10010506 POWELL RD 10010600 COEUR D ALENE NF 01 IDAHO COEUR D ALENE 10010700 COLVILLE NF 01 WASHINGTON COLVILLE 10010710 NE WASH LUP (COLVILLE) 01 WASHINGTON 10010800 CUSTER NF 01 MONTANA BILLINGS Page 1 09/20/11 02:07 PM Line Domain Code Domain Name Description Number 10010801 SHEYENNE RD 10010802 BEARTOOTH RD 10010803 SIOUX RD 10010804 ASHLANDFORT HOWES RD 10010806 GRAND RIVER RD 10010807 MEDORA RD 10010808 MCKENZIE RD 10010810 CEDAR RIVER NG 01 NORTH DAKOTA 10010820 DAKOTA PRAIRIES GRASSLAND 01 NORTH DAKOTA 10010830 SHEYENNE NG 01 NORTH DAKOTA 10010840 GRAND RIVER NG 01 SOUTH DAKOTA 10010900 DEERLODGE NF 01 MONTANA BUTTE 10010901 DEER LODGE RD 10010902 JEFFERSON RD 10010903 PHILIPSBURG RD 10010904 BUTTE RD 10010929 DILLON RD 01 MONTANA DILLON 11 LANDS IN BUTTE RD, DEERLODGE NF ADMIN 12 ISTERED BY THE DILLON RD, BEAVERHEAD NF. -

Copyrighted Material

INDEX ABC Television Studios 152 Chrysler Building 96, 102 Evelyn Apartments 143–4 Abyssinian Baptist Church 164 Chumley’s 66–8 Fabbri mansion 113 The Alamo 51 Church of the Ascension Fifth Avenue 56, 120, 140 B. Altman Building 96 60–1 Five Points 29–31 American Museum of Natural Church of the Incarnation 95 Flagg, Ernest 43, 55, 156 History 142–3 Church of the Most Precious Flatiron Building 93 The Ansonia 153 Blood 37 Foley Square 19 Apollo Theater 165 Church of St Ann and the Holy Forward Building 23 The Apthorp 144 Trinity 167 42nd Street 98–103 Asia Society 121 Church of St Luke in the Fields Fraunces Tavern 12–13 Astor, John Jacob 50, 55, 100 65 ‘Freedom Tower’ 15 Astor Library 55 Church of San Salvatore 39 Frick Collection 120, 121 Church of the Transfiguration Banca Stabile 37 (Mott Street) 33 Gangs of New York 30 Bayard-Condict Building 54 Church of the Transfiguration Gay Street 69 Beecher, Henry Ward 167, 170, (35th Street) 95 General Motors Building 110 171 City Beautiful movement General Slocum 70, 73, 74 Belvedere Castle 135 58–60 General Theological Seminary Bethesda Terrace 135, 138 City College 161 88–9 Boathouse, Central Park 138 City Hall 18 German American Shooting Bohemian National Hall 116 Colonnade Row 55 Society 72 Borough Hall, Brooklyn 167 Columbia University 158–9 Gilbert, Cass 9, 18, 19, 122 Bow Bridge 138–9 Columbus Circle 149 Gotti, John 40 Bowery 50, 52–4, 57 Columbus Park 29 Grace Court Alley 170 Bowling Green Park 9 Conservatory Water 138 Gracie Mansion 112, 117 Broadway 8, 92 Cooper-Hewitt National Gramercy -

Request for Proposals for the Performance Of

February 20, 2018 SUBJECT: REQUEST FOR PROPOSALS FOR THE PERFORMANCE OF EXPERT PROFESSIONAL PLANNING AND FEASIBILITY STUDY FOR THE WHARF REPLACEMENT PROGRAM DURING 2018 THROUGH 2020 (RFP #52133) Dear Sir or Madam: The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey (the “Authority”) is seeking proposals in response to this Request for Proposals (RFP) from prospective consultants (also “you,” “Firm” and “Proposer”) for the performance of expert planning and feasibility study for the wharf replacement program. The scope of the planning and feasibility study is to provide the Authority with a framework from which to plan the systematic replacement of its waterfront structures over a span of approximately thirty (30) years for its five (5) port facilities: Port Newark, Elizabeth-Port Authority Marine Terminal, Port Jersey-Port Authority Marine Terminal, Howland Hook Marine Terminal and Brooklyn-Port Authority Marine Terminal (“Wharf Replacement Program”). The term of the agreement between the Authority and the Consultant will be for two (2) years, with up to two (2) additional one (1) year option periods, upon the same terms, conditions and pricing, unless otherwise agreed to by the Authority. The scope of the services to be performed by you are set forth in Attachment A of the Authority’s Standard Agreement (the “Agreement”), included herewith as Exhibit II. You should carefully review this Agreement as it is the form of agreement that the Authority intends that you sign in the event of acceptance of your Proposal and forms the basis for the submission of Proposals. The services to be performed by the Consultant may be funded in whole or in part by the Federal Highway Administration, therefore Federally mandated terms and conditions are applicable (See Exhibit I for applicable Federal Highway Administration Requirements). -

Of the New Jersey Maritime Pi- Lot and Docking Pilot Commission

156th Annual Report Of The New Jersey Maritime Pi- lot and Docking Pilot Commission Dear Governor and Members of the New Jersey Legislature, In 1789, the First Congress of the United States delegated to the states the authority to regulate pilotage of vessels operating on their respective navigable waters. In 1837, New Jersey enacted legislation establishing the Board of Commissioners of Pilotage of the State of New Jersey. Since its creation the Commission has had the responsibility of licensing and regulating maritime pilots who direct the navigation of ships as they enter and depart the Port of New Jersey and New York. This oversight has contributed to the excellent reputation the ports of New Jersey and New York has and its pilots enjoy throughout the maritime world. New legislation that went into effect on September 1, 2004 enables the Commission to further contribute to the safety and security of the port by requiring the Commission to license docking pilots. These pilots specialize in the docking and undocking of vessels in the port. To reflect the expansion of its jurisdiction the Commission has been renamed “The New Jersey Maritime Pilot and Docking Pilot Commission.” In keeping with the needs of the times, the new legislation has a strong security component. All pilots licensed by the state will go through an on going security vetting. The Commission will issue badges and photo ID cards to all qualified pilots, which they must display when entering port facilities and boarding vessels. The legislation has also modernized and clarified the Commissions’ authority to issue regulations with respect to qualifications and training required for pilot licenses, pilot training (both initial and recurrent) accident investigation and drug and alcohol testing.