Stage 2 Report 1/11

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fatal Fire Investigation

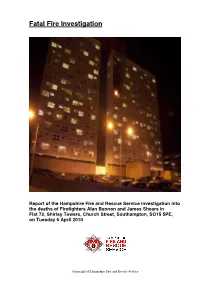

Fatal Fire Investigation Report of the Hampshire Fire and Rescue Service investigation into the deaths of Firefighters Alan Bannon and James Shears in Flat 72, Shirley Towers, Church Street, Southampton, SO15 5PE, on Tuesday 6 April 2010 Copyright of Hampshire Fire and Rescue Service Copyright of Hampshire Fire and Rescue Service 1 Foreword The primary duty of all fire and rescue services is to save life. In Hampshire this responsibility is central to how we operate such that the people we select and train, the equipment we buy and use, and the procedures we follow are focussed on that defining obligation. This report details the response to a fire which led to the deaths of two of our colleagues. The facts of the report and particularly the actions of all HFRS staff are framed by that duty to save life. On the night of 6 April 2010 many lives of the public were at risk in Shirley Towers, Church Street, Southampton, a 16 storey high rise block of residential flats. The scene faced by fire crews that night was frantic and frightening such that the efforts to tackle this difficult and dangerous fire required the courage, stamina and skill of all those involved. As an organisation we have dedicated considerable resources to this report, both in honour of our colleagues and also in a genuine desire to learn from these events. We have then ensured this learning has been turned into tangible actions in order to improve the way we tackle such incidents. We hope this will assist others, as well as ourselves, in understanding what caused the loss of Alan Bannon and James Shears and to do all we can to prevent such tragedies occurring in the future. -

Creating a Better Future Annual Report 2019 Our Core Values

CREATING A BETTER FUTURE ANNUAL REPORT 2019 OUR CORE VALUES The Immune Deficiency Foundation (IDF) improves the diagnosis, treatment, and quality of life of people affected by primary immunodeficiency (PI) through fostering a community empowered by advocacy, education, and research. Our core values are inclusion, integrity, and innovation. Inclusion can only occur when everyone within our community and beyond has the opportunity to belong, to be heard, to be valued. To uphold integrity, it’s critically important that we are trustworthy stewards for the PI community, putting their livelihood first. We will embrace challenges head-on with new solutions and ways to strengthen the PI community through innovation. In addition, we commit to serving our constituents with transparency, trust, and compassion. The Immune Deficiency Foundation is proud to be an equal opportunity employer. We are rare and we are powerful. Like the stripes of a zebra, no two people are the same, and at IDF, we celebrate this uniqueness every day. An inclusive, diverse, and fair workplace makes our community more powerful. At IDF, we build communities and programs for people living with PI. It’s through these services, that they can connect with other individuals, families, and healthcare professionals who are living and working with PI. In 2019, we implemented initiatives to foster relationships within the community, and provide rich and accurate information and resources to thousands. We helped advance research and worked collaboratively with expert clinicians from across the country to better understand patient experiences and improve outcomes. All those living with PI continue to rely on IDF for information and support, which is why we’ve made the commitment to ensure a better future for generations to come. -

Attendees by Member Type

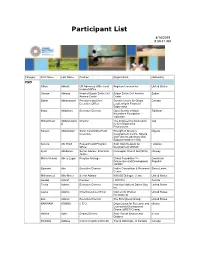

WSIA Annual Marketplace September 22-25, 2019 Attendee List as of September 17, 2019 U.S. Wholesale Members Member Firm Member Name Member Firm Member Name 5Star Specialty Programs Robert Alkire All Risks, Ltd. Jake Fratkin 5Star Specialty Programs David Tooley All Risks, Ltd. Matt Frein, CRIS 5Star Specialty Programs Alek Turko All Risks, Ltd. Amy Fuller Across America Insurance Services All Risks, Ltd. Frank Giarratano, II Inc. Harish Kapur All Risks, Ltd. Ryan Grimes Advanced E&S Group Scott Cook All Risks, Ltd. Jeff Gumaer Advanced E&S Group Brad Keller All Risks, Ltd. Glenn Hargrove Advanced E&S Group Lenika Milne All Risks, Ltd. Dawn Hickman Advanced E&S Group Matthew Power All Risks, Ltd. Jim Higgins Advanced E&S Group Harvey Sheldon, CPCU All Risks, Ltd. Emily Hughes, CPCU All Risks of CA, LLC Darren Chilimidos All Risks, Ltd. Beau Hume All Risks of CA, LLC Michael Potts All Risks, Ltd. Yasser Hussein All Risks of the Southeast Wes Baker All Risks, Ltd. Adam Jacobus All Risks of the Southeast Steve Kass All Risks, Ltd. Dave Kremer All Risks, Ltd. Todd Ballot All Risks, Ltd. Brad Lind All Risks, Ltd. Matt Bell All Risks, Ltd. Frank Martino All Risks, Ltd. Krystal Boggs All Risks, Ltd. Rick McDonough All Risks, Ltd. Lee Branson All Risks, Ltd. Christopher McGovern All Risks, Ltd. Josh Cantrell, RPLU, ASLI All Risks, Ltd. Dino Mirabal, CPCU All Risks, Ltd. Craig Carpenter All Risks, Ltd. Wesley Mitchell All Risks, Ltd. Nicholas Cortezi All Risks, Ltd. Hugh Mooney All Risks, Ltd. Trent Cox All Risks, Ltd. -

The Class of 2018 CAREERSTV Fair

January 2018 The class of 2018 CAREERSTV Fair 6 February 10:00am-4:00pm Business Design Centre, London N1 0QH Journal of The Royal Television Society January 2018 l Volume 55/1 From the CEO Welcome to 2018. In With luck, some of these industry Hector, who recalls a very special this issue of Television leaders will be joining RTS events in evening in Bristol when a certain we have assembled the coming months, so we can hear 91-year-old natural history presenter a line-up of features from them directly. was, not for the first time, the centre that reflects the new Following the excesses – and per- of attention. Did anyone mention TV landscape and haps stresses – of Christmas, our Janu- Blue Planet II? its stellar class of 2018. ary edition contains what I hope read- Our industry map looks like it’s Pictured on this month’s cover are ers will agree is some much-needed being redrawn dramatically. Disney’s some of the sector’s leaders who are light relief. Don’t miss Kenton Allen’s historic $52.4bn bid for 21st Century certain to be making a big splash in pulsating review of 2017. I guarantee Fox is among a number of moves the year ahead – Tim Davie, Ian Katz, that it’s laugh-out-loud funny. responding to the need for scale. We Jay Hunt, Carolyn McCall, Alex Mahon, Also bringing a light touch to this will be looking at this trend in the Simon Pitts and Fran Unsworth. month’s Television is Stefan Stern’s coming months. -

Awards Programme of Events

Celebrating 60 years of wins for writers PROGRAMME THE ROYAL COLLEGE OF PHYSICIANS 11 ST ANDREWS PLACE, REGENT’S PARK LONDON NW1 4LE MONDAY 14 JANUARY 2019 The Writers’ Guild of Great Britain is a trade union registered at 134 Tooley Street, London SE1 2TU @TheWritersGuild #wggbawards #wggb60 PRESIDENT’S WELCOME Welcome to the Writers’ Guild Awards 2019. Photo: Julie Brook Whilst our politicians never fail to I hope it hasn’t missed your notice that the disappoint us, writers, like vultures, Writers’ Guild turns 60 this year. 60 years LEAD SPONSOR look around with beady-eyed interest at of campaigning, negotiating, chasing, soothing carnage and adversity. Only a few years and championing. Formed when ITV was ago the complaint against the public was still a toddler and Bruce Forsyth presenting political apathy and lack of engagement. Sunday Night at the London Palladium, with film Be careful what you wish for… allegedly on its last legs due to the threat from television and radio considered a basket case, In such a climate of chaos and dissent we turn it challenged those predictions by bringing to our artists and writers to make sense of together writers from all these areas in the things for us and judging by the remarkable common cause of dignity in labour. Many things range and ambition of this year’s nominees, they have changed in the interim but as we stumble are thriving on the challenge. forwards together I commend that cause to you tonight. THANK YOU TO ALL OUR SPONSORS Olivia Hetreed WGGB President HISTORY OF THE AWARDS Since they were established in 1961, the Writers’ Guild of Great Britain Awards have been honouring the cream of British writers and writing. -

Participant List

Participant List 4/14/2019 8:59:41 AM Category First Name Last Name Position Organization Nationality CSO Jillian Abballe UN Advocacy Officer and Anglican Communion United States Head of Office Osman Abbass Head of Sudan Sickle Cell Sudan Sickle Cell Anemia Sudan Anemia Center Center Babak Abbaszadeh President and Chief Toronto Centre for Global Canada Executive Officer Leadership in Financial Supervision Ilhom Abdulloev Executive Director Open Society Institute Tajikistan Assistance Foundation - Tajikistan Mohammed Abdulmawjoo Director The Engineering Association Iraq d for Development & Environment Kassim Abdulsalam Zonal Coordinator/Field Strength in Diversity Nigeria Executive Development Centre, Nigeria and Farmers Advocacy and Support Initiative in Nig Serena Abi Khalil Research and Program Arab NGO Network for Lebanon Officer Development (ANND) Kjetil Abildsnes Senior Adviser, Economic Norwegian Church Aid (NCA) Norway Justice Maria Victoria Abreu Lugar Program Manager Global Foundation for Dominican Democracy and Development Republic (GFDD) Edmond Abu Executive Director Native Consortium & Research Sierra Leone Center Mohammed Abu-Nimer Senior Advisor KAICIID Dialogue Centre United States Aouadi Achraf Founder I WATCH Tunisia Terica Adams Executive Director Hamilton National Dance Day United States Inc. Laurel Adams Chief Executive Officer Women for Women United States International Zoë Adams Executive Director The Strongheart Group United States BAKINAM ADAMU C E O Organization for Research and Ghana Community Development Ghana -

Needs and Supports of Canadian and US Ethnocultural Arts Organizations

Figuring the Plural: Needs and Supports of Canadian and US Ethnocultural Arts Organizations Mina Para Matlon, Ingrid Van Haastrecht, Kaitlyn Wittig Mengüç School of the Art Institute of Chicago/Art Institute of Chicago 2014 This project was supported in part or in whole by an award from the Research: Art Works program at the National Endowment for the Arts: Grant# 13-3800-7011. The opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the Office of Research & Analysis or the National Endowment for the Arts. The NEA does not guarantee the accuracy or completeness of the information included in this report and is not responsible for any consequence of its use. Figuring the Plural Written, edited, and compiled by Mina Para Matlon Ingrid Van Haastrecht Kaitlyn Wittig Mengüç © 2014 by Plural All rights reserved. Published 2014. Printed in the United States of America Plural (http://pluralculture.com) is a project based out of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and dedicated to supporting Canadian and US ethnocultural arts organizations. The Plural project co-leads gratefully acknowledge the generous support of this research project by the Joyce Foundation, National Endowment for the Arts, and the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Text material (excluding artwork that appears as text such as script excerpts and poems) may be reprinted without permission for any non- commercial use, provided Plural is properly credited and its copyright is acknowledged. Permission to reproduce photographs or other artwork, or the artistic discipline profiles separate from the work as a whole, must be obtained from the copyright owner listed in the relevant credit. -

SUGGESTED TEXTS for the English K–10 Syllabus

SUGGESTED TEXTS for the English K–10 Syllabus SUGGESTED TEXTS for the English K–10 Syllabus © 2012 Copyright Board of Studies NSW for and on behalf of the Crown in right of the State of New South Wales. This document contains Material prepared by the Board of Studies NSW for and on behalf of the State of New South Wales. The Material is protected by Crown copyright. All rights reserved. No part of the Material may be reproduced in Australia or in any other country by any process, electronic or otherwise, in any material form or transmitted to any other person or stored electronically in any form without the prior written permission of the Board of Studies NSW, except as permitted by the Copyright Act 1968. School students in NSW and teachers in schools in NSW may copy reasonable portions of the Material for the purposes of bona fide research or study. Teachers in schools in NSW may make multiple copies, where appropriate, of sections of the HSC papers for classroom use under the provisions of the school’s Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) licence. When you access the Material you agree: to use the Material for information purposes only to reproduce a single copy for personal bona fide study use only and not to reproduce any major extract or the entire Material without the prior permission of the Board of Studies NSW to acknowledge that the Material is provided by the Board of Studies NSW not to make any charge for providing the Material or any part of the Material to another person or in any way make commercial use of the Material without the prior written consent of the Board of Studies NSW and payment of the appropriate copyright fee to include this copyright notice in any copy made not to modify the Material or any part of the Material without the express prior written permission of the Board of Studies NSW. -

Tidings Issue 24 Winter 2011

## %# "!1'3 ('1! '%1!!$ () )'0"3 &'(%$" $ !(') Free home delivery of all your stoma or continence prescription requirements. All ('1! (!$ manufacturers’ products stocked and supplied Electronic Prescription Service (EPS) Online ordering facility ' "!1'3 !(') ('1! Impartial product advice and complimentary sampling service 0"!)3 ((0' Quick, discreet and reliable overnight delivery $ $ 1! Deliveries can be made to any chosen 2' 2!$$!$ address (without a signature if required) 0()%#' ' Open on Saturdays ' !!) Extended midweek opening hours Ultrasonic, computerised cutting of all appliances to your exact stoma size/shape ISO Quality assured service Free gift and MRSA resistant flannel with 0800 220 300 first order Complimentary wet or dry wipes & perfumed www.ostomart.co.uk disposal bags with each order. You’ll be glad you did! Award winning personalised service BTEC qualified stoma & continence customer support staff !! Access to stoma care nurses for unbiased product advice and support Prescription collection from your GP if required FROM THE EDITOR welcome to WINTER care related conferences and CA I would also like to send out several volunteer training events as Editor of BIG messages of thanks and Tidings and the enthusiasm and appreciation...to our Dear Nurse...Julie appreciation of Tidings has brought a Rust – thank you! Julie always makes tear to my eye on several occasions time to answer your medical queries but I must stress it is a Team effort in Tidings even though she is which includes you! I cannot impress exceptionally busy. on you enough how well Tidings is received by healthcare professionals A big THANK YOU to the advertisers and in particular stoma care nurses who without their continued support, who regularly give Tidings to their Tidings magazine in its current form patients – a BIG thank you to them! would not be possible! And last but Happy New Year and definitely not least, kind thanks go to welcome to the winter Over the past year Tidings has the unsung heroes who continue to issue of Tidings.. -

EXERCISE NEPTUNE Live Casualty Exercise 2017 Author: Ben Collins, Emergency Preparedness Officer

Northern Devon Healthcare NHS Trust EXERCISE NEPTUNE Live Casualty Exercise 2017 Author: Ben Collins, Emergency Preparedness Officer Exercise Neptune Page 1 Northern Devon Healthcare NHS Trust Contents Contents ............................................................................................................................................................ 2 Foreword ........................................................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction ...................................................................................................................................................... 5 Scenario & Injects ............................................................................................................................................ 10 Objective 1: Safety ........................................................................................................................................... 14 Objective 2: Containment ................................................................................................................................. 17 Objective 3: Triage ........................................................................................................................................... 20 Objective 4: Decontamination .......................................................................................................................... 22 Objective 5: Patient Experience ....................................................................................................................... -

To Download Backbone Issue

BACKBONE ~ 100th issue ~ BACKBONE CONTENTS 3 Latest News 4 Treatment for Adult Degenerative Scoliosis 7 International Scoliosis Awareness Day 8 Eva Butterly 10 Scoliosis and breathing 14 SAUK Fundraising 17 Regional Representative updates 18 SAUK yesterday and today A note on the front cover 20 Coping with pain This is a special issue of Backbone, we have reached 100 and we wanted to commemorate this by commissioning David Rintoul a unique front cover. Hannah Webb is a 23 graphic design student at Manchester School of Art who is now seven years post Exercises for Adult Degenerative Scoliosis scoliosis surgery. She first created the 24 Wonky Spine illustration for an exhibition at the Whitworth, Manchester called ‘Take Hold’ which celebrated positive body image 27 Scoliosis Campaign Fund - thank you and self-worth. The design is of Hannah’s spine, pre-surgery. She said, ‘at the time I didn’t think it was mighty fine, but now I see Members stories on Adult Degenerative Scoliosis things differently. I hope this will encourage 28 others with scoliosis to feel the same.’ Editors: Stephanie Clark and Claire Curley Designed by: Emily Wilson Cover: Designed by Hannah Webb. Inside cover: Eva Butterly, © Stephen Black photography All uncaptioned images royalty free stock images, © Patrica Wamaitha Ng’ang’a or author’s own. Printed in Great Britain by The Lavenham Press on Pure White Silk, a silk coated, high quality paper made from 100% recycled fibre and fully FSC certified. Produced using 100% recycled waste at a mill that has been awarded the ISO14001 certificate for environmental management. -

Has Anything Really Changed?

ORIGINAL DOCUMENTARIES REFLECTING ORIGINAL DOCUMENTARIES REFLECTING ORIGINAL DOCUMENTARIES REFLECTING INSIDE THE SOCIAL BLACK BRITAIN: SEX BUSINESS HOUSING 50 YEARS ON FRONT COVER THEIR STORIES HOW DO WE HAS ANYTHING THEIR WORDS HOUSE THE REAL LY POOR? CHANGED? 23-25 AUGUST 2017 OFFICIAL PROGRAMME SPONSORED BY WEDNESDAY 23 FESTIVAL AT A GLANCE THE SPEAKERS AND CHAIRS 2017 FROM 09:00 FROM 09:30 10:00-11:00 BREAK 11:45-12:45 BREAK 13:45-14:45 BREAK 15:30-16:30 BREAK 17:30-18:15 18:15-21:00 SB Artisan SA Incognito F Nothing will be 11:00-11:45 P Edinburgh 12:45-13:45 P Meet the 14:45-15:30 P Meet the 16:30-17:30 L The Free coaches to Shane Allen Hannah Chambers Evan Davis Mark Gordon Christian Howes Jarmo Lampela Charlotte Moore Dani Rayner Chris Shaw Jane Turton Tea and Coffee provide a musical Televised: Have Does...Blue Peter Controller: Jay Controller: Kevin T SA MacTaggart The Museum of T Ones to Watch T Break Out FS Aidan Farrell, SA Plus Break Out Aperol Thursday 09:30 - 10:30 Friday 11:30 - 12:30 Thursday 13:30 - 14:30 Wednesday 13:45 - 14:45 Wednesday 10:00 - 11:00 Friday 11:05 - 11:50 Thursday 09:30 - 10:30 Wednesday 10:45 - 11:45 Friday 13:00 - 14:00 09:00 - 11.00 welcome to the Young People Hunt, Channel 4 Lygo, ITV Lecture: Scotland depart Wednesday 10:00 - 11:00 Random Acts S Satire! What is it Session: Show Star Colourist Meet the Sky Session: Delivering Spritzers The Pentland The Sidlaw The Pentland The Sidlaw The Moorfoot/Kilsyth The Tinto The Pentland The Tinto The Fintry Sky Arts Zone Switched Off? Jon Snow from the EICC