A. Design Resources Overview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2. Basic Roadway Improvements the Street System Provides the Basic Network for Bicycle Travel

Figure 2-1: Many low-volume resi- YES dential streets need only the most basic improve- ments to make them more ridable. 2. Basic Roadway Improvements The street system provides the basic network for bicycle travel. Other ele- ments (e.g., bike lanes and paths) supplement this system. To make most streets work for bicyclists, basic improvements may be needed. Such things as safe railroad crossings, traffic signals that work for bicyclists, and street networks that connect benefit bicyclists and make more bicycle trips possible and likely. 2.1 Roadway types While the most basic improvements are appropriate for all categories of street, some improvements are most appropriate for certain categories. In a typical community, streets types range from quiet residential streets, to minor collector streets, to major arterials, and highways or expressways. Figure 2-2: Long blocks and a lack 2.1.1 Residential streets of connectivity On quiet residential streets with little traffic and slow speeds (fig. 2-1), make trips longer bicyclists and motorists can generally co-exist with little difficulty. Such and discourage streets seldom need bike lanes. Only the most basic improvements may bicycling for pur- poseful trips. be required, for instance: • bicycle-safe drainage grates • proper sight distance at intersections • smooth pavement and proper maintenance One additional factor that may need attention is connectivity. Providing bicycle linkages between residential streets and nearby commercial areas or adjacent neighborhoods can significantly improve bicycling conditions. In many communi- 2-1 Wisconsin Bicycle Facility Design Handbook ties, newer parts of town tend to have dis- Figure 2-3: Bicycle- continuous street networks that require bicy- pedestrian connec- clists, pedestrians, and motorists to travel a tions like that long distance to get to a nearby destination shown can provide (fig. -

Pedestrian and Bicycle Friendly Policies, Practices, and Ordinances

Pedestrian and Bicycle Friendly Policies, Practices, and Ordinances November 2011 i iv . Pedestrian and Bicycle Friendly Policies, Practices, and Ordinances November 2011 i The Delaware Valley Regional Planning The symbol in our logo is Commission is dedicated to uniting the adapted from region’s elected officials, planning the official professionals, and the public with a DVRPC seal and is designed as a common vision of making a great region stylized image of the Delaware Valley. even greater. Shaping the way we live, The outer ring symbolizes the region as a whole while the diagonal bar signifies the work, and play, DVRPC builds Delaware River. The two adjoining consensus on improving transportation, crescents represent the Commonwealth promoting smart growth, protecting the of Pennsylvania and the State of environment, and enhancing the New Jersey. economy. We serve a diverse region of DVRPC is funded by a variety of funding nine counties: Bucks, Chester, Delaware, sources including federal grants from the Montgomery, and Philadelphia in U.S. Department of Transportation’s Pennsylvania; and Burlington, Camden, Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) Gloucester, and Mercer in New Jersey. and Federal Transit Administration (FTA), the Pennsylvania and New Jersey DVRPC is the federally designated departments of transportation, as well Metropolitan Planning Organization for as by DVRPC’s state and local member the Greater Philadelphia Region — governments. The authors, however, are leading the way to a better future. solely responsible for the findings and conclusions herein, which may not represent the official views or policies of the funding agencies. DVRPC fully complies with Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and related statutes and regulations in all programs and activities. -

Literature Review- Resource Guide for Separating Bicyclists from Traffic

Literature Review Resource Guide for Separating Bicyclists from Traffic July 2018 0 U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration NOTICE This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the U.S. Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The U.S. Government assumes no liability for the use of the information contained in this document. This report does not constitute a standard, specification, or regulation. The U.S. Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. Trademarks or manufacturers’ names appear in this report only because they are considered essential to the objective of the document. Technical Report Documentation Page 1. REPORT NO. 2. GOVERNMENT ACCESSION NO. 3. RECIPIENT'S CATALOG NO. FHWA-SA-18-030 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5. REPORT DATE Literature Review: Resource Guide for Separating Bicyclists from Traffic 2018 6. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION CODE 7. AUTHOR(S) 8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION Bill Schultheiss, Rebecca Sanders, Belinda Judelman, and Jesse Boudart (TDG); REPORT NO. Lauren Blackburn (VHB); Kristen Brookshire, Krista Nordback, and Libby Thomas (HSRC); Dick Van Veen and Mary Embry (MobyCON). 9. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME & ADDRESS 10. WORK UNIT NO. Toole Design Group, LLC VHB 11. CONTRACT OR GRANT NO. 8484 Georgia Avenue, Suite 800 8300 Boone Boulevard, Suite 300 DTFH61-16-D-00005 Silver Spring, MD 20910 Vienna, VA 22182 12. SPONSORING AGENCY NAME AND ADDRESS 13. TYPE OF REPORT AND PERIOD Federal Highway Administration Office of Safety 1200 New Jersey Ave., SE Washington, DC 20590 14. SPONSORING AGENCY CODE FHWA 15. SUPPLEMENTARY NOTES The Task Order Contracting Officer's Representative (TOCOR) for this task was Tamara Redmon. -

Evaluation of Concrete Pavements with Tied Shoulders Or Widened Lanes Bert E

39 19. K. Y. Kung. A New Method in Correlation Study of vision of Pavements. Proc., 3rd International Con Pavement Deflection and Cracking. Proc., 2nd In ference on Structural Design of Asphalt Pavements, ternational Conference on Structural Design of 1972, pp. 1188-1205. Asphalt Pavements, 1967, pp. 1037-1046. 20. P. H. Leger and P. Autret. The Use of Deflection Publication of this paper sponsored by Committee on Pavement Condi Measurements for the Structural Design and Super- tion Evaluation. Evaluation of Concrete Pavements With Tied Shoulders or Widened Lanes Bert E. Colley, Claire G. Ball, and Pichet Arriyavat, Portland Cement Association Field and laboratory pavements were instrumented and load tested to reducing pavement performance, Because of this prob evaluate the effect of widened lanes, concrete shoulders, and slab thick lem, several states have installed costly longitudinal ness on measured strains and deflectfons. Eight slabs were tested in the and transverse drainage systems. Thus, concrete field and two in the laboratory. Pavement slabs were 203, 229, or 254 shoulders and widened lanes have the potential for curing mm (8, 9, or 10 in) thick. Other major design variables included the width of lane widening, the presence or absence of dowels or of a con many drainage problems as well as providing additional crete shoulder, joint spacing, and the type of shoulder joint construc slab strength. tion. Generally, there was good agreement between measured strains and Many design features contribute to pavement life. values calculated by using Westergaard's theoretical equations. Concrete The effect of some of these features can be evaluated shoulders were effective in reducing the magnitude of measured strains analytically. -

Pedestrian and Bicycle Infrastructure Network Data Catalog

Pedestrian and Bicycle Infrastructure Network Data Catalog Created by Institute for Transportation Research and Education Bicycle and Pedestrian Program For North Carolina Department of Transportation Division of Bicycle and Pedestrian Transportation January 21, 2016 JANUARY 2016 PBIN DATA CATALOG PBIN Data Catalog Each dataset provides a consistent set of attribute fields on existing bicycle, pedestrian, and shared-use path data for use in asset management as well as proposed data for use in planning and project development by PGI awarded communities. Where applicable, fields or attributes marked with an asterisk (*) are required data for NCDOT Planning Grant Initiative (PGI) communities to collect and/or update as a condition of award. PGI communities should consider including additional fields or attributes from the Data Catalog when inventorying focus areas or corridors, as identified through the plan development process. The data catalog is broken up into three sections: 1. BICYCLE ASSETS The Bike_Fac_Linear feature class includes polyline data on existing and proposed facilities such as bike lanes, bike routes, bicycle boulevards, and paved shoulders. It also includes information on surface condition, facility width, slope, and rumble strips. The Bike_Fac_Point feature class includes polyline data on existing and proposed facilities such as bike parking, crossing improvement, bike boxes, bike share kiosks, and bike detection loops. It also includes information on bicycle-oriented signage and hazardous grates. It also includes information on surface condition, facility width, slope, and rumble strips. The Ped_Fac_Linear feature class includes polyline data on existing and proposed facilities such as sidewalks and other types of footpaths. It includes information on material, facility width, buffer, buffer width and slope. -

FHWA Bikeway Selection Guide

BIKEWAY SELECTION GUIDE FEBRUARY 2019 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave Blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED February 2019 Final Report 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5a. FUNDING NUMBERS Bikeway Selection Guide NA 6. AUTHORS 5b. CONTRACT NUMBER Schultheiss, Bill; Goodman, Dan; Blackburn, Lauren; DTFH61-16-D-00005 Wood, Adam; Reed, Dan; Elbech, Mary 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION VHB, 940 Main Campus Drive, Suite 500 REPORT NUMBER Raleigh, NC 27606 NA Toole Design Group, 8484 Georgia Avenue, Suite 800 Silver Spring, MD 20910 Mobycon - North America, Durham, NC 9. SPONSORING/MONITORING AGENCY NAME(S) 10. SPONSORING/MONITORING AND ADDRESS(ES) AGENCY REPORT NUMBER Tamara Redmon FHWA-SA-18-077 Project Manager, Office of Safety Federal Highway Administration 1200 New Jersey Avenue SE Washington DC 20590 11. SUPPLEMENTARY NOTES 12a. DISTRIBUTION/AVAILABILITY STATEMENT 12b. DISTRIBUTION CODE This document is available to the public on the FHWA website at: NA https://safety.fhwa.dot.gov/ped_bike 13. ABSTRACT This document is a resource to help transportation practitioners consider and make informed decisions about trade- offs relating to the selection of bikeway types. This report highlights linkages between the bikeway selection process and the transportation planning process. This guide presents these factors and considerations in a practical process- oriented way. It draws on research where available and emphasizes engineering judgment, design flexibility, documentation, and experimentation. 14. SUBJECT TERMS 15. NUMBER OF PAGES Bike, bicycle, bikeway, multimodal, networks, 52 active transportation, low stress networks 16. PRICE CODE NA 17. SECURITY 18. SECURITY 19. SECURITY 20. -

Approved-Bicycle-Master-Plan-Framework-Report.Pdf

MONTGOMERY COUNTY BICYCLE MASTER PLAN FRAMEWORK abstract This report outlines the proposed framework for the Montgomery County Bicycle Master Plan. It defines a vision by establishing goals and objectives, and recommends realizing that vision by creating a bicycle infrastructure network supported by policies and programs that encourage bicycling. This report proposes a monitoring program designed to make the plan implementation process both clear and responsive. 2 MONTGOMERY COUNTY BICYCLE MASTER PLAN FRAMEWORK contents 4 Introduction 6 Master Plan Purpose 8 Defining the Vision 10 Review of Other Bicycle Plans 13 Vision Statement, Goals, Objectives, Metrics and Data Requirements 14 Goal 1 18 Goal 2 24 Goal 3 26 Goal 4 28 Goals and Objectives Considered but Not Recommended 30 Realizing the Vision 32 Low-Stress Bicycling 36 Infrastructure 36 Bikeways 55 Bicycle Parking 58 Programs 58 Policies 59 Prioritization 59 Bikeway Prioritization 59 Programs and Policies 60 Monitoring the Vision 62 Implementation 63 Accommodating Efficient Bicycling 63 Approach to Phasing Separated Bike Lane Implementation 63 Approach to Implementing On-Road Bicycle Facilities Incrementally 64 Selecting A Bikeway Recommendation 66 Higher Quality Sidepaths 66 Typical Sections for New Bikeway Facility Types 66 Intersection Templates A-1 Appendix A: Detailed Monitoring Report 3 MONTGOMERY COUNTY BICYCLE MASTER PLAN FRAMEWORK On September 10, 2015, the Planning Board approved a Scope of Work for the Bicycle Master Plan. Task 4 of the Scope of Work is the development of a methodology report that outlines the approach to the Bicycle Master Plan and includes a discussion of the issues identified in the Scope of Work. -

Civitas Measure Directory 10 Years of Civitas from Aalborg to Zagreb

CIVITAS MEASURE DIRECTORY 10 YEARS OF CIVITAS FROM AALBORG TO ZAGREB A REFERENCE GUIDE TO SUSTAINABLE URBAN MOBILITY RESEARCH AND DEMONSTRATION MEASURES IMPLEMENTED BY EUROPEAN CITIES BETWEEN 2002 AND 2012 About CIVITAS The CIVITAS Initiative (“City-Vitality-Sustainability”, or “Cleaner and Better Transport in Cities”) was launched in 2002. Its fundamental aim is to support cities to introduce ambitious transport measures and policies towards sustainable urban mobility. The goal of CIVITAS is to achieve a significant shift in the modal split towards sustainable transport, an objective reached through encouraging both innovative technology and policy-based strategies. In the first phase of the project (2002 to 2006), 19 cities participated in four research and demonstration projects; and in CIVITAS II (2005 to 2009), 17 cities participated across a further four projects. The initiative has just reached the end of its third phase, CIVITAS Plus (2008 to 2013), in which 25 cities were working together on five collaborative projects. In 2012, the CIVITAS Plus II phase was launched, with seven European cities and one non-European city collaborating across two new projects. In total, more than 60 European cities have been co-funded by the European Commission to implement innovative measures in clean urban transport, an investment volume of well over EUR 300 million. But CIVITAS does not stop there. The so-called demonstration cities are part of the larger CIVITAS Forum network, which comprises more than 200 cities committed to implementing and integrating sustainable urban mobility measures. By signing a non-binding voluntary agreement known as the CIVITAS Declaration, cities and their citizens benefit from the accumulated know-how, experience and lessons learned of every participant. -

Appendix a Bicycle and Trail Design Guidelines

Riverton Active Transportation Master Plan Appendix A Bicycle and Trail Design Guidelines 2015 PREPARED BY: Alta Planning + Design 8 Broadway Salt Lake City, UT 84111 DRAFT Appendix A: Bicycle and Trail Design Guidelines Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................................................................................................1 Design Needs of Pedestrians ....................................................................................................................................................4 Design Needs of Bicyclists ..........................................................................................................................................................6 Bicycle Facility Selection Guidelines .......................................................................................................................................9 Facility Classification ....................................................................................................................................................................... 10 Facility Continua ................................................................................................................................................................................ 11 Bicycle Facility Contextual Guidance ........................................................................................................................................ 12 Shared Roadways ..........................................................................................................................................................................13 -

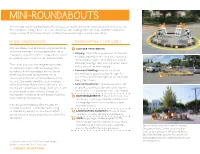

MINI-ROUNDABOUTS Mini-Roundabouts Or Neighborhood Traffic Circles Are an Ideal Treatment for Minor, Uncontrolled Intersections

MINI-ROUNDABOUTS Mini-roundabouts or neighborhood traffic circles are an ideal treatment for minor, uncontrolled intersections. The roundabout configuration lowers speeds without fully stopping traffic. Check out NACTO’s Urban Street Design Guide or FHWA’s Roundabout: An Information Guide Design Guide for more details. 4 DESIGN CONSIDERATIONS COMMON MATERIALS CATEGORIES 1 2 Mini-roundabouts can be created using raised islands 1 SURFACE TREATMENTS: and simple markings. Landscaping elements are an » Striping: Solid white or yellow lines can be used important component of the roundabout and should in conjunction with barrier element to demarcate be explored even for a short-term demonstration. the roundabout space. Other likely uses include crosswalk markings: solid lines to delineate cross- The roundabout should be designed with careful walk space and / or zebra striping. consideration to lane width and turning radius for vehicles. A mini-roundabout on a residential » Pavement Markings: May include shared lane markings to guide bicyclists through the street should provide approximately 15 ft. of 2 clearance from the corner to the widest point on intersection and reinforce rights of use for people the circle. Crosswalks should be used to indicate biking. (Not shown) where pedestrians should cross in advance of the » Colored treatments: Colored pavement or oth- roundabout. Shared lane markings (sharrows) should er specialized surface treatments can be used to be used to guide people on bikes through the further define the roundabout space (not shown). intersections, in conjunction with bicycle wayfinding 2 BARRIER ELEMENTS: Physical barriers (such as route markings if appropriate. delineators or curbing) should be used to create a strong edge that sets the roundabout apart Note: Becase roundabouts allow the slow, but from the roadway. -

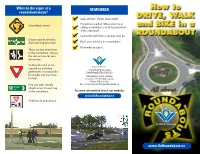

How to Drive, Walk & Bike in a Roundabout

What do the signs at a REMEMBER roundabout mean? Look and plan ahead. Slow down! Pedestrians go first. When entering or Roundabout ahead. exiting a roundabout, yield to pedestrians at the crosswalk. Look to the left, find a safe gap, then go. Choose your destination. Start planning your route. Don’t pass vehicles in a roundabout. Remember to signal. There are two entry lanes to the roundabout. Choose the correct lane for your destination. Yield to all traffic in the roundabout including TRANSPORTATION AND pedestrians at crosswalks. ENVIRONMENTAL SERVICES Remember you may have 150 Frederick Street, 7th Floor to stop! Kitchener ON N2G 4J3 Canada Phone: 519-575-4558 Flag exit signs identify Email: [email protected] street names for each leg of the roundabout. For more information check our website: www.GoRoundabout.ca Yield here to pedestrians. www.GoRoundabout.ca Updated January 2011 MOWTO HAT IS A ROUNDABOUT? HOW TO DRIVE IN A ROUNDABOUT TIPS FOR CYCLISTS A roundabout is an intersection at which ᮣ Slow down when A cyclist has two choices at a roundabout. Your all traffic circulates counterclockwise approaching a choice will depend on your degree of comfort riding roundabout. in traffic. around a centre island. ᮣ Observe lane signs. For experienced cyclists: Choose the correct ● Ride as if you were driving entry lane. a car. Yield Line ᮣ Expect pedestrians ● Merge into the travel lane Central and yield to them at before the bike lane or shoulder ends. Island all crosswalks. ● Ride in the middle of your lane; don’t hug the curb. Turning right and turning left ᮣ Wait for a gap in ● Use hand signals and signal as if you were a traffic before motorist. -

Lessons from the Green Lanes: Evaluating Protected Bike Lanes in the U.S

NATIONAL INSTITUTE FOR TRANSPORTATION AND COMMUNITIES FINAL REPORT Lessons from the Green Lanes: Evaluating Protected Bike Lanes in the U.S. NITC-RR-583 June 2014 A University Transportation Center sponsored by the U.S. Department of Transportation LESSONS FROM THE GREEN LANES: EVALUATING PROTECTED BIKE LANES IN THE U.S. FINAL REPORT NITC-RR-583 Portland State University Alta Planning Independent Consultant June 2014 Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient’s Catalog No. NITC-RR-583 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date Lessons From The Green Lanes: June 2014 Evaluating Protected Bike Lanes In The U.S. 6. Performing Organization Code 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. Chris Monsere, Jennifer Dill, Nathan McNeil, Kelly Clifton, Nick Foster, Tara Goddard, Matt Berkow, Joe Gilpin, Kim Voros, Drusilla van Hengel, Jamie Parks 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) Chris Monsere Portland State University P.O. Box 751 Portland, Oregon 97207 11. Contract or Grant No. NITC-RR-583 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period Covered National Institute for Transportation and Communities (NITC) Final Report P.O. Box 751 Portland, Oregon 97207 14. Sponsoring Agency Code 15. Supplementary Notes 16. Abstract This report presents finding from research evaluating U.S. protected bicycle lanes (cycle tracks) in terms of their use, perception, benefits, and impacts. This research examines protected bicycle lanes in five cities: Austin, TX; Chicago, IL; Portland, OR; San Francisco, CA; and Washington, D.C., using video, surveys of intercepted bicyclists and nearby residents, and count data.