Dunn, a (2018) Curating the Sound of the Word Revolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The End of the Loudness War?

The End Of The Loudness War? By Hugh Robjohns As the nails are being hammered firmly into the coffin of competitive loudness processing, we consider the implications for those who make, mix and master music. In a surprising announcement made at last Autumn's AES convention in New York, the well-known American mastering engineer Bob Katz declared in a press release that "The loudness wars are over.” That's quite a provocative statement — but while the reality is probably not quite as straightforward as Katz would have us believe (especially outside the USA), there are good grounds to think he may be proved right over the next few years. In essence, the idea is that if all music is played back at the same perceived volume, there's no longer an incentive for mix or mastering engineers to compete in these 'loudness wars'. Katz's declaration of victory is rooted in the recent adoption by the audio and broadcast industries of a new standard measure of loudness and, more recently still, the inclusion of automatic loudness-normalisation facilities in both broadcast and consumer playback systems. In this article, I'll explain what the new standards entail, and explore what the practical implications of all this will be for the way artists, mixing and mastering engineers — from bedroom producers publishing their tracks online to full-time music-industry and broadcast professionals — create and shape music in the years to come. Some new technologies are involved and some new terminology too, so I'll also explore those elements, as well as suggesting ways of moving forward in the brave new world of loudness normalisation. -

Dublin's Bid to Host FIG Working Week 2019

Dublin’s bid to host Dublin’sFIG bid Working to host Week 2019 FIG Working Week 2019 Custom House Dublin CONTENTS 2 MOTIVATION FOR THE BID 43 ACCOMMODATION 8 LETTERS OF SUPPORT 46 SUSTAINABILITY 17 LOCAL ORGANISING COMMITTEE 49 SOCIAL PROGRAMME 21 AGENCY ASSISTANCE 55 TECHNICAL TOURS 23 DUBLIN AS A CONFERENCE 58 PRE & POST CONFERENCE TOURS DESTINATION 62 DUBLIN – CITY OF LIVING CULTURE 28 ACCESS 66 GOLFING IN IRELAND 31 BUDGET 68 MAPS 34 PROPOSED VENUE: THE CONVENTION CENTRE DUBLIN 1 MOTIVATION FOR THE BID Four Courts Dublin MOTIVATION FOR THE BID The motivation for the Irish bid comes on a number of levels. The Society of Chartered Surveyors Ireland, as the national association representing members across the surveying disciplines, has in recent years developed rapidly and reorganised into a vibrant professional body, with over 5,500 members, playing an active role in national development. Ireland has a long and notable history of surveying and measurement from the carefully aligned network of hill-top monuments constructed over 5,000 years ago, to the completion of the world’s first large-scale national mapping in the mid nineteenth century and, in the last decade, the National Seabed Survey that ranks amongst the largest marine mapping programmes undertaken anywhere in the world. Meanwhile, Ireland has one of the most open economies in the world and most of the major international IT companies have established bases in Ireland. At the same time, young Irish graduates can be found bringing their skills and enthusiasm to all corners of the world and, in many cases, returning home enriched professionally and culturally by their time abroad. -

Download the Storyman Stories Booklet

CDB_Album_Stories_Booklet.qxp 23/09/2006 15:05 Page 1 Stories CDB_Album_Stories_Booklet.qxp 23/09/2006 15:05 Page 2 DUBLIN, 2006. One World Leningrad "Welcome to The Storyman Project! “And what is this place?” said the old man, one has ever proved even exist, and seem to ST PETERSBURG, 1969. From the moment The Storyman Theme stroking his long white beard. delight in trying to destroy not only themselves An attractive, well-dressed woman in her mid- begins, join me on a journey through “Planet Earth, sir,” replied the ship’s Captain. but also the whole planet, with everything else forties walks down a street in a quiet, affluent space and time, to faraway lands and “Well, take me a bit closer, and let’s have a on it!” suburb of this beautiful city, a street of well- places, where the tales and dramas will look. Is it one of mine?” “I say, leave them at it,” offered the Captain. kept gardens and expensive, old-money unfold. Each one of the songs is “Yes sir,” the Captain responded, “but the Evil “Let them taste the results of their own homes set back from the road behind high accompanied by a story that will set the One is also trying to stake a claim.” stupidity.” walls. She crosses the road, a wall to her right, scene, expand on the lyrics with detail, “How’s he doing?” asked the old man. “No,” said the old man drawing a heavy sigh; ivy spilling down to the ground and trees heavy colour and atmosphere, and the musical “He’s doing pretty well right now,” said the “I’m going to have to intervene, try and bang with leaves that shield a large house within. -

Basel Family Magazine Team—Will Introduce Their Products and Services That Are Available to You, in English, in the Basel Area

The New Messehalle Summer Be a Night Owl at the Get Fit in Basel’s Unveiled Camps! Basel Zoo Parks Volume 1 Issue 8 MAGAZINE A Family Guide to Discovering Basel for the Expat Community JUNE 2013 Basel Takes Art Seriously L I F E TRAVEL EVENTS DINING LETTER FROM THE EDITOR Dear Readers, MAGAZINE If you are a fan of the arts, Basel is the place to be in June! JUNE 2013 Volume 1 • Issue 8 The world famous Art Basel will be taking over the mid- dle of this month, with a host of exhibitions, indoor and TABLE OF CONTENTS outdoor art events, and a multitude of related art fairs. This month is also rich with activities that serve the Feature Story: The New Messehalle 3expat community of Basel. For example, you won’t want to miss the annual Expat Expo on June 2, where about 100 exhibitors catering to the expat community—including your Special Event: Art Basel 4-5 Basel Family Magazine team—will introduce their products and services that are available to you, in English, in the Basel area. You also may be interested in a large sale of June Events in Basel 6-8 second-hand English-language books and other media. And finally, if you are fairly new to Basel, be sure to join the “Basel for Newcomers Tour” on June 1. Fun Family Outings Beyond Basel 9 And as usual, the impressive lineup of concerts by inter- national artists, English theater, tours, workshops, and Special Feature: Summer Camps! 10-13 entertainment in the Basel area will offer something for everyone. -

Chris De Burgh the Getaway Mp3, Flac, Wma

Chris de Burgh The Getaway mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock / Pop Album: The Getaway Style: Soft Rock, Pop Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1565 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1360 mb WMA version RAR size: 1722 mb Rating: 4.9 Votes: 764 Other Formats: ADX AUD DXD MP1 MOD MP3 AA Tracklist Hide Credits A1 Don't Pay The Ferryman 3:47 Living On The Island A2 3:30 Electric Guitar, Acoustic Guitar – Tim Wynveen Crying And Laughing A3 4:34 Electric Guitar, Acoustic Guitar – Tim Wynveen I'm Counting On You A4 4:25 Cello – Nigel Warren-GreenPiano – David Caddick A5 The Getaway 3:42 Ship To Shore B1 3:49 Programmed By – Rupert Hine B2 All The Love I Have Inside 3:15 Borderline B3 4:38 Piano – Chris de Burgh Where Peaceful Waters Flow B4 3:56 Programmed By – Rupert Hine B5a The Revolution 9:03 Light A Fire B5b Electric Guitar, Acoustic Guitar – Tim Wynveen Liberty B5c Electric Guitar, Acoustic Guitar – Tim Wynveen Credits Art Direction, Photography By [Back Cover] – Michael Ross Bass, Bass [Fretless] – John Giblin Drums – Steve Negus Electric Guitar, Acoustic Guitar – Phil Palmer Guitar, Backing Vocals, Written-By – Chris de Burgh Illustration – Syd Brak Other [Management] – Dave Margereson, Kenny Thomson Photography By [Inner Sleeve] – Fin Costello Producer [Assistant], Engineer, Woodwind, Saxophone – Stephen W. Tayler Producer, Synthesizer, Percussion, Backing Vocals, Performer [Orchestral Arrangements Played By] – Rupert Hine Saxophone – Anthony Thistlethwaite Typography – Andrew Ellis Vocals [Additional] – Anthony Head, Diane Davison, Miriam Stockley, Sue Wilkinson, Tim Wynveen Notes On the vinyl label, the following additional numbers are listed: AMLH 68549 (Both sides) SMX-59293 (Side A) / SMX-59294 (Side B) - these two matrix numbers are also etched in the run-out groove. -

Chris De Burgh

Chris de Burgh Christopher J. Davison alias Chris de Burgh, was born in Venado Tuerto, Argentina on October 15, 1948. He is the son of Charles Davison, a British diplomat, and an Irish secretary, Maeve Emily de Burgh. His childhood was rich in travel and experience due to his fathers’ diplomatic and engineering work. He grew up in different countries, such as Malta, Nigeria and Zaire. When he was 12 years old the Davison family moved to Emerald Isle, Ireland. Chris still lives there, with his wife Diane and their three children, Rosanna, Hubie, and Michael. In 1960, his grandfather, General Sir Eric de Burgh, bought an old castle ‘Bargy Castle’, which originally was built in the 12th century. After the Davisons renovated the castle, they opened it up as a half year holiday hotel for families. Chris held his first concerts in this castle and he used it to play and sing for the guests in the evenings. He learned to play the guitar by the ‘Learning by doing’ method. He studied English and French at the famous Trinity College in Dublin. This gave him ideas for his own lyrics. He began writing songs while studying French and English at Trinity College in Dublin where he earned his Master of Arts degree in French, English, and History. He also attended Malborough College in England. In 1971, Chris moved to London to pursue his music career. He was singing in a hamburger restaurant and a hair dresser's shop. He was looking for a job and was offered by a friend to sing in a recently opened restaurant in Dublin called ‘Captain Americas’. -

Teaching Traditional Music Theory with Popular Songs

s leaching Traditional Music Theory with Popular Songs: Pitch Structures Heather Maclachlan 1' his chapter provides a guideline for teaching conventi�nal, common Pr actice period music theory concepts using well-known English-language P opular songs. I developed the lessons included here in the a-ucible of the u niversity classroom while teaching music theory to undergraduate students t � Cornell University in 2007. This approach to teaching theory, therefore, as the advantage of having been created in conjunction with recent stu- d e�ts, who ultimately demonsu·ated mastery of the concepts presented and en1oyed doing so. While this tactic has not been tested with a large enough r g oup of students to provide reliable data, it is clear that the students who P�rticipated in these lessons deeply appreciated the oppo1tunity, and they at � � �s much on their course evaluations, all of which were quite positive. ndiv1duals made comments like, "It was ina-edible to hear what we were 1 earning in pieces that we knew," and "The teacher should write her own �eJctbook using examples from modern m\tSic! ! ! " This chapter represents a trst attempt at presenting this approach to a larger audience. BENEFITS OF INCORPORATING CONTEMPORARY-POP SONGS INTO TRADITIONAL MUSIC-THEORY CLASSES 'l'h. story of how I came to use this approach to music theory demonstrates s e orne important pedagogical principles. I was working as a teaching assis t ant for a professor of music theory who had developed a clear and consis t ent approach to the topic. Over the course of about 20 years, he honed his curriculum. -

Within My First Introduction to the Estate Newsletter

Summer/Autumn 2006 ● Issue No.12 HOLKHAM NEWSLETTER ithin my first introduction to the Estate Newsletter six months ago, I promised to continue my father’s programme of change. Change has to be handled sensitively, as some people find it difficult to adapt to. W However, it may amuse many of you who know me, to discover that I have been ‘hoisted by my own petard’, in that I have not found taking over responsibility of the Estate to be as seamless as I had expected. During the past 10 years, I have been very ‘hands-on’ at Holkham, running three or four Estate businesses and getting involved in the nitty gritty. Now, I too am learning to let go, step back from the detail and take on more of a Chairman’s role. On the subject of change, Holkham Farming Company will shortly be moving to its newly built premises at Egmere, alongside the grain store.This re-location should make its previous base at Longlands, a safer place and also allow Holkham Building Maintenance to continue to expand.As you will read on page 14, Building Maintenance has taken on nine Hector’s Housing employees and the management team has been strengthened by the appointment of David Smith, to a new position of Property Manager. Property forms a huge part of Holkham Estate’s portfolio with approximately 400 buildings (many of them listed), including 325 houses, farm barns and commercial property. It is important we accord these historic assets the care and respect they deserve, not least because of their increasing value. -

Download Adelaide Festival Guide

ADELAIDEFESTIVAL.COM.AU WELCOME Jay Weatherill Premier of South Australia 2 Welcome to the Adelaide Festival. Enjoyed amid warm March days and starry nights, it has been long-recognised as one of the world’s best arts events. Now an annual fixture, it ignites the city’s passion for the very best in theatre, dance, opera, literature, music, film and the visual arts. 2013 brings audiences a breathtaking dance series featuring one of the greatest dancers of our time, Sylvie Guillem, flamenco master Carlos Saura and contemporary dance powerhouse Wim Vandekeybus. Theatre experiences range from the large-scale to the intimate with Broadway hit One Man, Two Guvnors and Belgian company Ontroerend Goed’s award-winning immersive and interactive trilogy series. Local talent shines with highly- anticipated events across the program, including the awe-inspiring Adelaide Symphony Orchestra and a massed 60-voice choir giving new life to 1968 sci-fi masterpiece film 2001: A Space Odyssey. American performance artist Laurie Anderson collaborating with the Kronos Quartet will be a feature of the strong music program, which also includes a beautiful free evening in Elder Park with Adelaide-born singer songwriter Paul Kelly and celebrated New Zealand performer Neil Finn. Adelaide Writers’ Week again offers insights into great contemporary writers and writing, mostly in open air, and uniquely free, sessions. The hugely popular late-night club Barrio returns and is bound to be a highlight again. These attractions are just the beginning of this wide-ranging program of exclusive shows, internationally acclaimed artists and inclusive events. I look forward to seeing you there. -

THE SAVOY THEATRE, Limerick, Ireland EVENTS

THE SAVOY THEATRE, Limerick, Ireland EVENTS – MARCH 1966 to FEBRUARY 1988 This is an attempt to start a comprehensive listing of events which took place at this venue. I am taking March 1966 as my start date as I am personally interested in the Savoy as a venue for rock, pop and folk shows and the first such show took place at that time. However, I am happy to accept additions for prior to that date. Hopefully, with your help, we will eventually have a full listing. The list below has been made through newspaper research and my own personal list of events which I attended between 1978 and 1987 and there are certainly many omissions. It is also likely that there are events listed here that didn’t in fact take place – some concerts were advertised or mentioned in the newspaper and were subsequently cancelled – where the cancellation was not recorded in the newspaper the listing remains. All corrections & additions welcome, supporting evidence particularly welcome. I would also love to get information about support acts – a lot of local acts would be among them and it would be great to have them recorded. Mike Maguire – [email protected] DATE MAIN ACT SUPPORT/GUEST ACT(S) PRICE NOTES VENUE (Theatre unless otherwise indicated) 13/03/1966 Tops of the Town 22/03/1966 Joe Dolan & The Drifters The Ludlows, The Creatures, 8/6, 6/6 “New Spotlight presents late nite The Axills, The Empire variety spectacular” Showband 10/04/1966 Midnight Variety Concert 01/05/1966 Artane Boys Band & others 08/06/1966 The Ludlows Jim Farley Bandshow, Colours, -

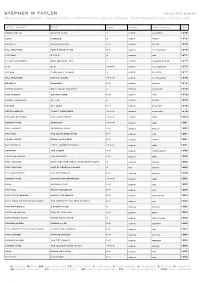

Stephen W Tayler

stephen w tayler selected works recording - mixing - production - composition - sound design - post-production - visual art artist - project title work project label - company year tommy bolin private eyes m album columbia 1976 gong gazeuse m album virgin 1976 brand x moroccan roll r-m album island 1976 bill bruford feels good to me r-m album e g records 1976 city boy 5 7 0 5 m single cbs 1977 claude francois quelquefois etc m album disques fleche 1977 u. k. u. k. cp-r-m album e g records 1977 voyage from east to west m album polydor 1977 bill bruford one of a kind cp-r-m album e g records 1978 brand x masques r-m album island 1978 peter gabriel 2nd album ‘scratch’ m tracks charisma 1978 rod argent moving home r-m album mca 1978 stomu yamashta go too m album arista 1978 voyage fly away r-m album polydor 1978 peter gabriel i don’t remember cp-r-m single charisma 1979 edward reekers the last forest cp-r-m album a&m 1980 rupert hine immunity cp-r-m album a&m 1981 the planets intensive care r-m single rialto 1980 the fixx the shuttered room r-m album mca 1981 jonah lewie heart skips beat r-m album stiff 1981 the models local and/or general cp-r-m album a&m 1981 caravan the album r-m album independent 1982 chris de burgh the getaway r-m album a&m 1982 phil collins don’t let her steal your heart away m single virgin 1982 phil collins live at perkins palace m vhs virgin 1982 the waterboys the waterboys r-m tracks ensign 1982 rupert hine waving not drowning cp-r-m album a&m 1983 saga worlds apart r-m album cbs 1983 the fixx reach the beach r-m album mca 1983 the little heroes watch the world r-m album emi/capitol 1983 the lords of the new church the lords of the new church r-m album irs 1983 the waterboys a pagan place m tracks ensign 1983 chris de burgh man on the line r-m album a&m 1984 honeymoon suite honeymoon suite m album wea canada 1984 howard jones human’s lib. -

Kilternan Klips

KKSummer 2017.FINALqxp.qxp_Layout 1 02/06/2017 08:44 Page 1 KILTERNAN KLIPS Building community, strengthening worship, growing in service The quarterly newsletter of Kilternan Parish, Co. Dublin The Rector on ... Clarity of vision few weeks ago, my sermon began with a story about a ‘All too often we get Aplace called Mike’s Chili from the Greek word koinonia. It Parlor. Mike’s was a regular pit stop sidelined into activities means more than simply hanging for Julie and me when we lived in out together or belonging to the Seattle. Mike made chili. Chili went ... that take us further same social club. Koinonia with everything—fries, hot dogs, away from our core sense of living our lives as ifhas we this burgers, even spaghetti. One item belonged to one another. It is the on the menu stood out: the grilled mission. We need to be deepest understanding of cheese sandwich. Firstly, it was the reminded that we are community, where we participate in only item that didn’t have chili on one another’s lives, in one another’s it; secondly, it cost a whopping $56. here for a purpose ... joys and in one another’s sufferings. When I asked them why the the Kingdom of God. This is the community we aspire to grilled cheese cost so much, they ’ build. replied, ‘We are a chili bar, we make If you are reading our parish chili round here, we want to make is the Kingdom of God. magazine for the first time, we hope sure no one orders a grilled cheese At Kilternan Parish we have that you will consider being part of sandwich’.