Differencing and Unit Root Tests

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Getting to Grips with Unix and the Linux Family

Getting to grips with Unix and the Linux family David Chiappini, Giulio Pasqualetti, Tommaso Redaelli Torino, International Conference of Physics Students August 10, 2017 According to the booklet At this end of this session, you can expect: • To have an overview of the history of computer science • To understand the general functioning and similarities of Unix-like systems • To be able to distinguish the features of different Linux distributions • To be able to use basic Linux commands • To know how to build your own operating system • To hack the NSA • To produce the worst software bug EVER According to the booklet update At this end of this session, you can expect: • To have an overview of the history of computer science • To understand the general functioning and similarities of Unix-like systems • To be able to distinguish the features of different Linux distributions • To be able to use basic Linux commands • To know how to build your own operating system • To hack the NSA • To produce the worst software bug EVER A first data analysis with the shell, sed & awk an interactive workshop 1 at the beginning, there was UNIX... 2 ...then there was GNU 3 getting hands dirty common commands wait till you see piping 4 regular expressions 5 sed 6 awk 7 challenge time What's UNIX • Bell Labs was a really cool place to be in the 60s-70s • UNIX was a OS developed by Bell labs • they used C, which was also developed there • UNIX became the de facto standard on how to make an OS UNIX Philosophy • Write programs that do one thing and do it well. -

Linking + Libraries

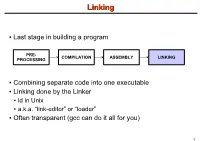

LinkingLinking ● Last stage in building a program PRE- COMPILATION ASSEMBLY LINKING PROCESSING ● Combining separate code into one executable ● Linking done by the Linker ● ld in Unix ● a.k.a. “link-editor” or “loader” ● Often transparent (gcc can do it all for you) 1 LinkingLinking involves...involves... ● Combining several object modules (the .o files corresponding to .c files) into one file ● Resolving external references to variables and functions ● Producing an executable file (if no errors) file1.c file1.o file2.c gcc file2.o Linker Executable fileN.c fileN.o Header files External references 2 LinkingLinking withwith ExternalExternal ReferencesReferences file1.c file2.c int count; #include <stdio.h> void display(void); Compiler extern int count; int main(void) void display(void) { file1.o file2.o { count = 10; with placeholders printf(“%d”,count); display(); } return 0; Linker } ● file1.o has placeholder for display() ● file2.o has placeholder for count ● object modules are relocatable ● addresses are relative offsets from top of file 3 LibrariesLibraries ● Definition: ● a file containing functions that can be referenced externally by a C program ● Purpose: ● easy access to functions used repeatedly ● promote code modularity and re-use ● reduce source and executable file size 4 LibrariesLibraries ● Static (Archive) ● libname.a on Unix; name.lib on DOS/Windows ● Only modules with referenced code linked when compiling ● unlike .o files ● Linker copies function from library into executable file ● Update to library requires recompiling program 5 LibrariesLibraries ● Dynamic (Shared Object or Dynamic Link Library) ● libname.so on Unix; name.dll on DOS/Windows ● Referenced code not copied into executable ● Loaded in memory at run time ● Smaller executable size ● Can update library without recompiling program ● Drawback: slightly slower program startup 6 LibrariesLibraries ● Linking a static library libpepsi.a /* crave source file */ … gcc .. -

AR400 User Guide 2.7.1

AR400 SERIES User Guide Software Release 2.7.1 AR410 AR440S AR441S AR450S AR400 Series Router User Guide for Software Release 2.7.1 Document Number C613-02021-00 REV F. Copyright © 2004 Allied Telesyn International Corp. 19800 North Creek Parkway, Suite 200, Bothell, WA 98011, USA. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced without prior written permission from Allied Telesyn. Allied Telesyn International Corp. reserves the right to make changes in specifications and other information contained in this document without prior written notice. The information provided herein is subject to change without notice. In no event shall Allied Telesyn be liable for any incidental, special, indirect, or consequential damages whatsoever, including but not limited to lost profits, arising out of or related to this manual or the information contained herein, even if Allied Telesyn has been advised of, known, or should have known, the possibility of such damages. All trademarks are the property of their respective owner. Contents CHAPTER 1 Introduction Why Read this User Guide? ............................................................................... 7 Where To Find More Information ...................................................................... 8 The Documentation Set .............................................................................. 8 Technical support .............................................................................................. 9 Features of the Router ..................................................................................... -

The Linux Command Line

The Linux Command Line Fifth Internet Edition William Shotts A LinuxCommand.org Book Copyright ©2008-2019, William E. Shotts, Jr. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No De- rivative Works 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit the link above or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042. A version of this book is also available in printed form, published by No Starch Press. Copies may be purchased wherever fine books are sold. No Starch Press also offers elec- tronic formats for popular e-readers. They can be reached at: https://www.nostarch.com. Linux® is the registered trademark of Linus Torvalds. All other trademarks belong to their respective owners. This book is part of the LinuxCommand.org project, a site for Linux education and advo- cacy devoted to helping users of legacy operating systems migrate into the future. You may contact the LinuxCommand.org project at http://linuxcommand.org. Release History Version Date Description 19.01A January 28, 2019 Fifth Internet Edition (Corrected TOC) 19.01 January 17, 2019 Fifth Internet Edition. 17.10 October 19, 2017 Fourth Internet Edition. 16.07 July 28, 2016 Third Internet Edition. 13.07 July 6, 2013 Second Internet Edition. 09.12 December 14, 2009 First Internet Edition. Table of Contents Introduction....................................................................................................xvi Why Use the Command Line?......................................................................................xvi -

BASIC UNIX COMMANDS FILES and DIRECTORIES All Information Is Stored in files

BASIC UNIX COMMANDS FILES AND DIRECTORIES All information is stored in files. File names and COMMANDS commands are case sensitive. Case matters. Files Commands are what you type at the prompt. Com- are contained in directories. You start out in your mands have arguments on which they operate. For own home directory, and your prompt usually tells example, in rm temp, the command is rm and the ar- its name. At any given time, one of these directories gument is temp; this command removes the file called is your working directory, the one you are in. temp. Here I put arguments in UPPER CASE. Thus, You can refer to files in your working directory by words such as FILE are taken to stand for some other just their names. You can refer to a file that is in a word, such as temp. In the following list, I use [ ] for subdirectory by giving a subdirectory name, a slash, optional arguments that are not typicaly used. and the file name, e.g., Mail/baron. You can refer to Commands have options that are controlled with any file on the computer by giving its full name, start- switches, which are usually letters following a single ing with a slash, such as /home7/b/baron/mbox. dash. Usually you can write several letters after one dash. For example ls -l lists files in a long format, If the file is a program, typing its name will run it. with more information. ls -a lists all the files, in- (That is what commands do.) If the program is some- cluding those that begin with ., which are usually thing you have just written and is in the director you files used by various programs. -

Zypper Cheat Sheet Or Type M an Zypper on a Terminal

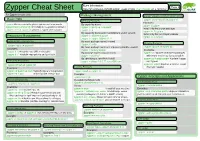

More Information: Page 1 Zypper Cheat Sheet https://en.opensuse.org/SDB:Zypper_usage or type m an zypper on a terminal For Zypper version 1.0.9 Package Management Source Packages and Build Dependencies Basic Help Selecting Packages zypper source-install or zypper si Examples: zypper #list the available global options and commands By capability name: zypper si zypper zypper help [command] #Print help for a specific command zypper in 'perl(Log::Log4perl)' Install only the source package zypper shell or zypper sh #Open a zypper shell session zypper in qt zypper in -D zypper By capability name and/or architecture and/or version Install only the build dependencies zypper in 'zypper<0.12.10' Repository Management zypper in -d zypper zypper in zypper.i586=0.12.11 Listing Defined Repositories By exact package name (--name) Updating Packages zypper in -n ftp zypper repos or zypper lr By exact package name and repository (implies --name) zypper update or zypper up Examples: zypper in factory:zypper Examples: zypper lr -u #include repo URI on the table By package name using wildcards zypper up #update all installed packages zypper lr -P #include repo priority and sort by it zypper in yast*ftp* with newer version as far as possible By specifying a .rpm file to install zypper up libzypp zypper #update libzypp Refreshing Repositories zypper in skype-2.0.0.72-suse.i586.rpm and zypper zypper refresh or zypper ref zypper in sqlite3 #update sqlite3 or install Installing Packages Examples: if not yet installed zypper ref packman main #specify repos to be -

APPENDIX a Aegis and Unix Commands

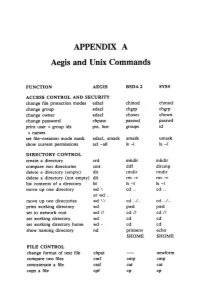

APPENDIX A Aegis and Unix Commands FUNCTION AEGIS BSD4.2 SYSS ACCESS CONTROL AND SECURITY change file protection modes edacl chmod chmod change group edacl chgrp chgrp change owner edacl chown chown change password chpass passwd passwd print user + group ids pst, lusr groups id +names set file-creation mode mask edacl, umask umask umask show current permissions acl -all Is -I Is -I DIRECTORY CONTROL create a directory crd mkdir mkdir compare two directories cmt diff dircmp delete a directory (empty) dlt rmdir rmdir delete a directory (not empty) dlt rm -r rm -r list contents of a directory ld Is -I Is -I move up one directory wd \ cd .. cd .. or wd .. move up two directories wd \\ cd . ./ .. cd . ./ .. print working directory wd pwd pwd set to network root wd II cd II cd II set working directory wd cd cd set working directory home wd- cd cd show naming directory nd printenv echo $HOME $HOME FILE CONTROL change format of text file chpat newform compare two files emf cmp cmp concatenate a file catf cat cat copy a file cpf cp cp Using and Administering an Apollo Network 265 copy std input to std output tee tee tee + files create a (symbolic) link crl In -s In -s delete a file dlf rm rm maintain an archive a ref ar ar move a file mvf mv mv dump a file dmpf od od print checksum and block- salvol -a sum sum -count of file rename a file chn mv mv search a file for a pattern fpat grep grep search or reject lines cmsrf comm comm common to 2 sorted files translate characters tic tr tr SHELL SCRIPT TOOLS condition evaluation tools existf test test -

Differential Response: a Primer for Child Welfare Professionals

FACTSHEETS | OCTOBER 2020 Differential Response: A Primer for Child Welfare Professionals Recognizing that a one-size-fits-all approach WHAT'S INSIDE does not serve children and families well, many agencies have implemented differential response Overview (DR), a system reform that establishes multiple pathways to respond to child maltreatment reports. DR routes families with a screened- Approaches to implementing differential response in report of child maltreatment through a traditional investigation pathway or an alternative assessment response pathway, depending on Differential response in the field other State policies and program requirements. Rather than initiating an investigation every time a family has a screened-in report, DR practice Conclusion seeks to assess a family's needs and connect them with services that will help them keep their References children safe. By linking families with services that will strengthen their ability to safely care for their children, DR can reduce the number of children entering foster care and decrease future involvement with the child welfare system. This factsheet provides child welfare professionals with an overview of DR and considerations for practice. Children's Bureau/ACYF/ACF/HHS | 800.394.3366 | Email: [email protected] | https://www.childwelfare.gov 1 OVERVIEW Both pathways share underlying principles and goals, including a focus on child safety, DR—also called alternative response, family permanency, and well-being, and include assessment response, multiple response, child safety and/or risk assessments. The or dual track—is a way of structuring child pathway assignment for a family could change protective services (CPS) to allow for more based on new information, such as potential flexibility in how it responds to low- and criminal behavior or imminent danger of moderate-risk cases and better meet the maltreatment. -

Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States, 2019

ANTIBIOTIC RESISTANCE THREATS IN THE UNITED STATES 2019 Revised Dec. 2019 This report is dedicated to the 48,700 families who lose a loved one each year to antibiotic resistance or Clostridioides difficile, and the countless healthcare providers, public health experts, innovators, and others who are fighting back with everything they have. Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States, 2019 (2019 AR Threats Report) is a publication of the Antibiotic Resistance Coordination and Strategy Unit within the Division of Healthcare Quality Promotion, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Suggested citation: CDC. Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States, 2019. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2019. Available online: The full 2019 AR Threats Report, including methods and appendices, is available online at www.cdc.gov/DrugResistance/Biggest-Threats.html. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15620/cdc:82532. ii U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Contents FOREWORD .............................................................................................................................................V EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................ VII SECTION 1: THE THREAT OF ANTIBIOTIC RESISTANCE ....................................................................1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................................3 -

An Introduction to R Notes on R: a Programming Environment for Data Analysis and Graphics Version 4.1.1 (2021-08-10)

An Introduction to R Notes on R: A Programming Environment for Data Analysis and Graphics Version 4.1.1 (2021-08-10) W. N. Venables, D. M. Smith and the R Core Team This manual is for R, version 4.1.1 (2021-08-10). Copyright c 1990 W. N. Venables Copyright c 1992 W. N. Venables & D. M. Smith Copyright c 1997 R. Gentleman & R. Ihaka Copyright c 1997, 1998 M. Maechler Copyright c 1999{2021 R Core Team Permission is granted to make and distribute verbatim copies of this manual provided the copyright notice and this permission notice are preserved on all copies. Permission is granted to copy and distribute modified versions of this manual under the conditions for verbatim copying, provided that the entire resulting derived work is distributed under the terms of a permission notice identical to this one. Permission is granted to copy and distribute translations of this manual into an- other language, under the above conditions for modified versions, except that this permission notice may be stated in a translation approved by the R Core Team. i Table of Contents Preface :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 1 1 Introduction and preliminaries :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 2 1.1 The R environment :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 2 1.2 Related software and documentation ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 2 1.3 R and statistics :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 2 1.4 R and the window system :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: -

Matchport AR Embedded Device Server Command Reference

MatchPort AR Embedded Device Server Command Reference Part Number 900-502 Revision D November 2013 Intellectual Property © 2013 Lantronix, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of the contents of this book may be transmitted or reproduced in any form or by any means without the written permission of Lantronix. MatchPort and Lantronix are registered trademarks of Lantronix, Inc. in the United States and other countries. Evolution OS is a registered trademark of Lantronix, Inc. in the United States. DeviceInstaller is a trademark of Lantronix, Inc. U.S. patent 8,024,446. Additional patents pending. Windows and Internet Explorer are registered trademark of Microsoft Corporation. Mozilla and Firefox are registered trademarks of the Mozilla Foundation. Chrome is a trademark of Google, Inc. All other trademarks and trade names are the property of their respective holders. Contacts Lantronix, Inc. Corporate Headquarters 167 Technology Drive Irvine, CA 92618, USA Toll Free: 800-526-8766 Phone: 949-453-3990 Fax: 949-453-3995 Technical Support Online: www.lantronix.com/support Sales Offices For a current list of our domestic and international sales offices, go to the Lantronix web site at www.lantronix.com/about/contact. Disclaimer The information in this guide may change without notice. The manufacturer assumes no responsibility for any errors that may appear in this guide. For the latest revision of this product document, please check our online documentation at www.lantronix.com/support/documentation. Revision History Date Rev. Comments April 2008 A Initial Document September 2008 B Technical updates throughout, corresponding to release 1.1.0.0 R6. May 2010 C Updated for firmware release 5.1.0.0 R10. -

Is-Ar-10-010)

July 22, 2010 ROSS PHILO EXECUTIVE VICE PRESIDENT AND CHIEF INFORMATION OFFICER DEBORAH J. JUDY DIRECTOR, INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY OPERATIONS CHARLES L. MCGANN, JR. MANAGER, CORPORATE INFORMATION SECURITY SUBJECT: Audit Report – UNIX Operating System Master Controls (Report Number IS-AR-10-010) This report presents the results of our audit of UNIX® operating system master controls (Project Number 10RG005IT000). We conducted this audit in support of the Postal Service’s regulatory requirement to comply with section 404, Management’s Assessment of Internal Control, of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 (SOX). Our objective was to determine whether the Postal Service’s UNIX operating system environment, hosting applications supporting the financial statements, complies with Information Technology (IT) SOX master controls.1 This audit addresses operational risk. See Appendix A for additional details about this audit. In December 2006, Congress passed the Postal Accountability and Enhancement Act (the Postal Act) that included significant changes to the way the Postal Service does business. The Postal Act requires the Postal Service to comply with SOX beginning with the fiscal year (FY) 2010 annual report. Conclusion The UNIX operating system environment, hosting applications supporting the financial statements, generally complies with IT SOX master controls. See Appendix C for a summary of compliance with the UNIX master controls that we tested. Specifically, we tested UNIX servers and UNIX workstations and noted the following: All servers complied with the administrative password management, segregation of duties, and password encryption master controls. 1 Controls designed to mitigate the risk associated with the infrastructure that supports SOX in-scope applications. UNIX Operating System Master Controls IS-AR-10-010 One server did not comply with Two servers did not comply with .