Estimating the Extent of Illicit Drug Use in Palestine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

West Bank and Gaza 2020 Human Rights Report

WEST BANK AND GAZA 2020 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Palestinian Authority basic law provides for an elected president and legislative council. There have been no national elections in the West Bank and Gaza since 2006. President Mahmoud Abbas has remained in office despite the expiration of his four-year term in 2009. The Palestinian Legislative Council has not functioned since 2007, and in 2018 the Palestinian Authority dissolved the Constitutional Court. In September 2019 and again in September, President Abbas called for the Palestinian Authority to organize elections for the Palestinian Legislative Council within six months, but elections had not taken place as of the end of the year. The Palestinian Authority head of government is Prime Minister Mohammad Shtayyeh. President Abbas is also chairman of the Palestine Liberation Organization and general commander of the Fatah movement. Six Palestinian Authority security forces agencies operate in parts of the West Bank. Several are under Palestinian Authority Ministry of Interior operational control and follow the prime minister’s guidance. The Palestinian Civil Police have primary responsibility for civil and community policing. The National Security Force conducts gendarmerie-style security operations in circumstances that exceed the capabilities of the civil police. The Military Intelligence Agency handles intelligence and criminal matters involving Palestinian Authority security forces personnel, including accusations of abuse and corruption. The General Intelligence Service is responsible for external intelligence gathering and operations. The Preventive Security Organization is responsible for internal intelligence gathering and investigations related to internal security cases, including political dissent. The Presidential Guard protects facilities and provides dignitary protection. -

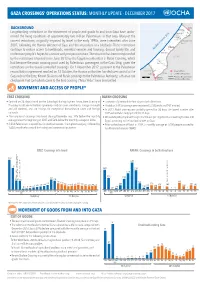

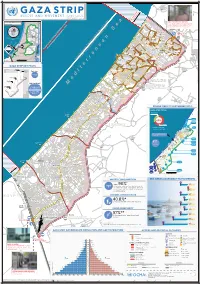

Gaza Crossings' Operations Status: Monthly

GAZA CROSSINGS’ OPERATIONS STATUS: MONTHLY UPDATE - DECEMBER 2017 BACKGROUND Erez Beit Lahiya ¹ ! Longstanding restrictions on the movement of people and goods to and from Gaza have under- ! Jabalya ! Beit Hanoun mined the living conditions of approximately two million Palestinians in that area. Many of the Gaza City ! n Sea ! Ash Shuja’iyeh current restrictions, originally imposed by Israel in the early 1990s, were intensified after June anea Nahal Oz Karni 2007, following the Hamas takeover of Gaza and the imposition of a blockade. These restrictions iterr GAZA Med 21 continue to reduce access to livelihoods, essential services and housing, disrupt family life, and 30! 0 undermine people’s hopes for a secure and prosperous future. The situation has been compounded Deir al B alah by the restrictions imposed since June 2013 by the Egyptian authorities at Rafah Crossing, which ISRAEL ! had become the main crossing point used by Palestinian passengers in the Gaza Strip, given the Khan Yunis Khuza’a ! restrictions on the Israeli-controlled crossings. On 1 November 2017, pursuant to the Palestinian 14389 Rafah EGYPT ! Crossing Point reconciliation agreement reached on 12 October, the Hamas authorities handed over control of the Sufa Rafah¹º» Closed Crossing Point Armistice Declaration Line Gaza side of the Erez, Kerem Shalom and Rafah crossings to the Palestinian Authority; a Hamas-run 5 Km ¹º» Kerem checkpoint that controlled access to the Erez crossing (“Arba’ Arba’”) was dismantled. Shalom International Boundary MOVEMENT AND ACCESS OF PEOPLE* EREZ CROSSING RAFAH CROSSING • Opened on 26 days (closed on five Saturdays) during daytime hours, from Sunday to • Exceptionally opened for four days in both directions. -

Nablus Salfit Tubas Tulkarem

Iktaba Al 'Attara Siris Jaba' (Jenin) Tulkarem Kafr Rumman Silat adh DhahrAl Fandaqumiya Tubas Kashda 'Izbat Abu Khameis 'Anabta Bizzariya Khirbet Yarza 'Izbat al Khilal Burqa (Nablus) Kafr al Labad Yasid Kafa El Far'a Camp Al Hafasa Beit Imrin Ramin Ras al Far'a 'Izbat Shufa Al Mas'udiya Nisf Jubeil Wadi al Far'a Tammun Sabastiya Shufa Ijnisinya Talluza Khirbet 'Atuf An Naqura Saffarin Beit Lid Al Badhan Deir Sharaf Al 'Aqrabaniya Ar Ras 'Asira ash Shamaliya Kafr Sur Qusin Zawata Khirbet Tall al Ghar An Nassariya Beit Iba Shida wa Hamlan Kur 'Ein Beit el Ma Camp Beit Hasan Beit Wazan Ein Shibli Kafr ZibadKafr 'Abbush Al Juneid 'Azmut Kafr Qaddum Nablus 'Askar Camp Deir al Hatab Jit Sarra Salim Furush Beit Dajan Baqat al HatabHajja Tell 'Iraq Burin Balata Camp 'Izbat Abu Hamada Kafr Qallil Beit Dajan Al Funduq ImmatinFar'ata Rujeib Madama Burin Kafr Laqif Jinsafut Beit Furik 'Azzun 'Asira al Qibliya 'Awarta Yanun Wadi Qana 'Urif Khirbet Tana Kafr Thulth Huwwara Odala 'Einabus Ar Rajman Beita Zeita Jamma'in Ad Dawa Jafa an Nan Deir Istiya Jamma'in Sanniriya Qarawat Bani Hassan Aqraba Za'tara (Nablus) Osarin Kifl Haris Qira Biddya Haris Marda Tall al Khashaba Mas-ha Yasuf Yatma Sarta Dar Abu Basal Iskaka Qabalan Jurish 'Izbat Abu Adam Talfit Qusra Salfit As Sawiya Majdal Bani Fadil Rafat (Salfit) Khirbet Susa Al Lubban ash Sharqiya Bruqin Farkha Qaryut Jalud Kafr ad Dik Khirbet Qeis 'Ammuriya Khirbet Sarra Qarawat Bani Zeid (Bani Zeid al Gharb Duma Kafr 'Ein (Bani Zeid al Gharbi)Mazari' an Nubani (Bani Zeid qsh Shar Khirbet al Marajim 'Arura (Bani Zeid qsh Sharqiya) Bani Zeid 'Abwein (Bani Zeid ash Sharqiya) Sinjil Turmus'ayya. -

Beneficiary and Community Perspectives on the Palestinian National Cash Transfer Programme

TRANSFORMING COUNTRY BRIEFING CASH TRANSFERS Beneficiary and community perspectives on the Palestinian National Cash Transfer Programme transformingcashtransfers.org Introduction transformingcashtransfers.org Our research aimed to explore the perceptions of cash transfer programme beneficiaries and implementers and other community members, in order to ensure their views are better reflected in policy and programming. Introduction transformingcashtransfers.org There is growing evidence internationally of positive links Key points: between social protection and poverty and vulnerability reduction. However, there has been limited recognition of the • De-developmental policies, recurring social inequalities that perpetuate poverty, such as gender insecurity and dependency on donor inequality, unequal citizenship status and displacement funding are among the key challenges through conflict, and the role social protection can play in in advancing social protection in the tackling these interlinked socio-political vulnerabilities. Occupied Palestinian Territories. • The Palestinian National Cash Transfer This country briefing synthesises qualitative research focusing Programme is an important but on beneficiary and community perceptions of the Palestinian limited component of female-headed National Cash Transfer Programme (PNCTP) in Gaza1 and households’ coping repertoires. West Bank2, as part of a broader research project in five countries (Kenya, Mozambique, OPT, Uganda and Yemen) by • Programme governance requires urgent the Overseas Development -

Gaza CRISIS)P H C S Ti P P I U

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs occupied Palestinian territory Zikim e Karmiya s n e o il Z P m A g l in a AGCCESSA ANDZ AMOV EMENTSTRI (GAZA CRISIS)P h c s ti P P i u F a ¥ SEPTEMBER 2014 o nA P N .5 F 1 Yad Mordekhai EREZ CROSSING (BEIT HANOUN) occupied Palestinian territory: ID a As-Siafa OPEN, six days (daytime) a B?week4 for B?3the4 movement d Governorates e e of international workers and limited number of y h s a b R authorized Palestinians including aid workers, medical, P r 2 e A humanitarian cases, businessmen and aid workers. Jenin d 1 e 0 Netiv ha-Asara P c 2 P Tubas r Tulkarm r fo e S P Al Attarta Temporary Wastewater P n b Treatment Lagoons Qalqiliya Nablus Erez Crossing E Ghaboon m Hai Al Amal r Fado's 4 e B? (Beit Hanoun) Salfit t e P P v i Al Qaraya al Badawiya i v P! W e s t R n m (Umm An-Naser) n i o » B a n k a North Gaza º Al Jam'ia ¹¹ M E D I TER RAN EAN Hatabiyya Ramallah da Jericho d L N n r n r KJ S E A ee o Beit Lahia D P o o J g Wastewater Ed t Al Salateen Beit Lahiya h 5 Al Kur'a J a 9 P l D n Treatment Plant D D D D 9 ) D s As Sultan D 1 2 El Khamsa D " Sa D e J D D l i D 0 D s i D D 0 D D d D D m 2 9 Abedl Hamaid D D r D D l D D o s D D a t D D c Jerusalem D D c n P a D D c h D D i t D D s e P! D D A u P 0 D D D e D D D a l m d D D o i t D D l i " D D n . -

Needle Sharing Among Intravenous Drug Abusers: National and International Perspectives

Needle Sharing Among Intravenous Drug Abusers: National and International Perspectives U. S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES • Public Health Service • Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration Needle Sharing Among Intravenous Drug Abusers: National and International Perspectives Editors: Robert J. Battjes, D.S.W. Roy W. Pickens, Ph.D. Division of Clinical Research National Institute on Drug Abuse NIDA Research Monograph 80 1988 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES Public Health Service Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration National Institute on Drug Abuse 5600 Fishers Lane Rockville, MD 20857 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, DC 20402 NIDA Research Monographs are prepared by the research divisions of the National Institute on Drug Abuse and published by its Office of Science. The primary objective of the series is to provide critical reviews of research problem areas and techniques, the content of state-of-the-art conferences, and integrative research reviews. Its dual publication emphasis is rapid and targeted dissemination to the scientific and professional community. Editorial Advisors MARTIN W. ADLER, Ph.D. MARY L. JACOBSON Temple University School of Medrcrne National Federation of Parents for Philadelphia. Pennsylvania Drug-Free Youth Omaha, Nebraska SYDNEY ARCHER, Ph.D. Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute Troy, New York REESE T. JONES, M.D. Langley Porter Neuropsychiatric lnstitute RICHARD E. BELLEVILLE. Ph.D. San Francisco, California NB Associates, Health Sciences RockviIle, Maryland DENISE KANDEL, Ph.D. KARST J. BESTEMAN College of Physicians and Surgeons of Alcohol and Drug Problems Association Columbia University of North America New York, New York Washington, D. -

Treatment of Alzheimer's Disease and Blood–Brain Barrier Drug Delivery

pharmaceuticals Review Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease and Blood–Brain Barrier Drug Delivery William M. Pardridge Department of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 90024, USA; [email protected] Received: 24 October 2020; Accepted: 13 November 2020; Published: 16 November 2020 Abstract: Despite the enormity of the societal and health burdens caused by Alzheimer’s disease (AD), there have been no FDA approvals for new therapeutics for AD since 2003. This profound lack of progress in treatment of AD is due to dual problems, both related to the blood–brain barrier (BBB). First, 98% of small molecule drugs do not cross the BBB, and ~100% of biologic drugs do not cross the BBB, so BBB drug delivery technology is needed in AD drug development. Second, the pharmaceutical industry has not developed BBB drug delivery technology, which would enable industry to invent new therapeutics for AD that actually penetrate into brain parenchyma from blood. In 2020, less than 1% of all AD drug development projects use a BBB drug delivery technology. The pathogenesis of AD involves chronic neuro-inflammation, the progressive deposition of insoluble amyloid-beta or tau aggregates, and neural degeneration. New drugs that both attack these multiple sites in AD, and that have been coupled with BBB drug delivery technology, can lead to new and effective treatments of this serious disorder. Keywords: blood–brain barrier; brain drug delivery; drug targeting; endothelium; Alzheimer’s disease; therapeutic antibodies; neurotrophins; TNF inhibitors 1. Introduction Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) afflicts over 50 million people world-wide, and this health burden costs over 1% of global GDP [1]. -

Community Resilience Development

Annexes Annex 1: Evaluation Terms of Reference Annex 2: The Concept of Resilience Annex 3: Bibliography Annex 4: List of Documents Reviewed Annex 5: List of people met: interviewees, focus groups, field visits Annex 6: List of field visits Annex 7: Sample of Projects for Document Review Annex 8: Maps, Vulnerability and Resilience Data Annex 9: Analysis of CRDP Project Portfolio Profile Annex 10: Vulnerability Analysis Annex 11: Universal Lessons on Gender-Sensitive Resilience-Based programming Annex 12: Field Work Calendar Annex 13: Achievements of Programme (Rounds 1-3) 1 Annex 1: Evaluation Terms of Reference 1. BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT About the CRDP The Community Resilience Development Programme (CRDP) is the result of a fruitful cooperation between the Palestinian Government through the Ministry of Finance and Planning (MOFAP, the United Nations Development Programme/Programme of Assistance to the Palestinian People (UNDP/PAPP), and the Government of Sweden. In 2012, an agreement was signed between the Government of Sweden and UNDP/PAPP so as to support a three-year programme (from 2012 to 2016), with a total amount of SEK 90,000,000, equivalent to approximately USD 12,716,858. During the same year, the UK’s Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) joined the program and provided funds for the first year with an amount of £300,000, equivalent to USD 453,172. In 2013, the government of Austria joined the programme and deposited USD 4,202,585, (a final amount of approximately $557,414 remains to be deposited) to support the programme for two years. Finally, in 2014, the Government of Norway joined the programme with a contribution of USD 1,801,298 to support the programme for two years. -

Analysis of Anthrax Immune Globulin Intravenous with Antimicrobial Treatment in Injection Drug Users, Scotland, 2009–2010 Xizhong Cui,1 Leisha D

RESEARCH Analysis of Anthrax Immune Globulin Intravenous with Antimicrobial Treatment in Injection Drug Users, Scotland, 2009–2010 Xizhong Cui,1 Leisha D. Nolen,1 Junfeng Sun, Malcolm Booth, Lindsay Donaldson, Conrad P. Quinn, Anne E. Boyer, Katherine Hendricks, Sean Shadomy, Pieter Bothma, Owen Judd, Paul McConnell, William A. Bower, Peter Q. Eichacker This activity has been planned and implemented through the joint providership of Medscape, LLC and Emerging Infectious Diseases. Medscape, LLC is accredited by the American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC), the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE), and the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME), to provide continuing education for the healthcare team. Medscape, LLC designates this Journal-based CME activity for a maximum of 1.00 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s)™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity. All other clinicians completing this activity will be issued a certificate of participation. To participate in this journal CME activity: (1) review the learning objectives and author disclosures; (2) study the education content; (3) take the post-test with a 75% minimum passing score and complete the evaluation at http://www.medscape.org/journal/eid; and (4) view/print certificate. For CME questions, see page 175. Release date: December 15, 2016; Expiration date: December 15, 2017 Learning Objectives Upon completion of this activity, participants will be able to: 1. Assess recommendations for the management of systemic anthrax and the use of anthrax immune globulin intravenous (AIG-IV) 2. Distinguish variables associated with the application of AIG-IV in the current study 3. -

Supervised Injection Services: What Has Been Demonstrated?

Drug and Alcohol Dependence 145 (2014) 48–68 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Drug and Alcohol Dependence j ournal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/drugalcdep Review Supervised injection services: What has been demonstrated? ଝ A systematic literature review a,b,∗ c,d e a,b Chloé Potier , Vincent Laprévote , Franc¸ oise Dubois-Arber , Olivier Cottencin , a,b Benjamin Rolland a Department of Addiction Medicine, CHRU de Lille, Univ Lille Nord de France, F-59037 Lille, France b University of Lille 2, Faculty of Medicine, F-59045 Lille, France c CHU Nancy, Maison des Addictions, Nancy F-54000, France d CHU Nancy, Centre d’Investigation Clinique CIC-INSERM 9501, Nancy F-54000, France e Institute of Social and Preventive Medicine, University Hospital Center and University of Lausanne, Chemin de la Corniche 10, 1010 Lausanne, Switzerland a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: Background: Supervised injection services (SISs) have been developed to promote safer drug injection Received 18 May 2014 practices, enhance health-related behaviors among people who inject drugs (PWID), and connect PWID Received in revised form 14 October 2014 with external health and social services. Nevertheless, SISs have also been accused of fostering drug use Accepted 14 October 2014 and drug trafficking. Available online 23 October 2014 Aims: To systematically collect and synthesize the currently available evidence regarding SIS-induced benefits and harm. Keywords: Methods: A systematic review was performed via the PubMed, Web of Science, and ScienceDirect Supervised injection service databases using the keyword algorithm [(“SUPERVISED” OR “SAFER”) AND (“INJECTION” OR “INJECT- Safer injection facility ING” OR “SHOOTING” OR “CONSUMPTION”) AND (“FACILITY” OR “FACILITIES” OR “ROOM” OR “GALLERY” Supervised injecting center Drug consumption room OR “CENTRE” OR “SITE”)]. -

Prescription Stimulants

Prescription Stimulants What are prescription stimulants? Prescription stimulants are medicines generally used to treat attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and narcolepsy— uncontrollable episodes of deep sleep. They increase alertness, attention, and energy. What are common prescription stimulants? • dextroamphetamine (Dexedrine®) • dextroamphetamine/amphetamine combination product (Adderall®) • methylphenidate (Ritalin®, Concerta®). Photo by ©iStock.com/ognianm Popular slang terms for prescription stimulants include Speed, Uppers, and Vitamin R. How do people use and misuse prescription stimulants? Most prescription stimulants come in tablet, capsule, or liquid form, which a person takes by mouth. Misuse of a prescription stimulant means: Do Prescription Stimulants Make You • taking medicine in a way or dose Smarter? other than prescribed Some people take prescription stimulants to • taking someone else’s medicine try to improve mental performance. Teens • taking medicine only for the effect it and college students sometimes misuse causes—to get high them to try to get better grades, and older adults misuse them to try to improve their When misusing a prescription stimulant, memory. Taking prescription stimulants for people can swallow the medicine in its reasons other than treating ADHD or normal form. Alternatively, they can crush narcolepsy could lead to harmful health tablets or open the capsules, dissolve the powder in water, and inject the liquid into a effects, such as addiction, heart problems, vein. Some can also snort or smoke the or psychosis. powder. Prescription Stimulants • June 2018 • Page 1 How do prescription stimulants affect the brain and body? Prescription stimulants increase the activity of the brain chemicals dopamine and norepinephrine. Dopamine is involved in the reinforcement of rewarding behaviors. -

23 November 2020

3 - 23 November 2020 Latest development (outside the reporting period) On 25 November, citing the lack of building permits, the Israeli authorities demolished 11 Palestinian-owned structures in the Massafer Yatta area of southern Hebron. These included homes, livelihood-related structures and water and sanitation facilities, some of which had been previously provided as humanitarian assistance. Twenty-five people were displaced and over 700 were otherwise affected. All but one of the seven communities targeted are located in an area designated closed for military training, and are at risk of a forcible transfer. This report exceptionally covers three weeks; the next issue will be released on 10 December, covering the normal two-week period. During the reporting period (3-23 November), a total of 129 structures were demolished, or seized, due to a lack of Israeli-issued building permits, displacing 100 people and otherwise affecting at least 200. The largest incident took place on 3 November in , where 83 structures were destroyed, displacing 73 people, including 41 children. Thirty more structures were demolished in 12 other Area C communities. The remaining 16 took place in East Jerusalem, where demolitions have resumed after a three-week suspension, following an announcement by the Israeli authorities on 1 October that, due to the pandemic, they would stop the demolition of inhabited residential buildings in the city. More structures have been demolished or seized so far in 2020, than in any complete year since OCHA began systematically documenting this practice in 2009, with the exception of 2016. On 4 November, Israeli forces shot and killed an off-duty member of the Palestinian security forces at a checkpoint south of Nablus city, reportedly after he opened fire at soldiers.