Mass Shootings As the New Normal: an Evaluation of Wikipedia Data and Flashbulb Memories As a Measurement of Public Perception

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Active Shooter - What Will You Do?

ACTIVE SHOOTER - WHAT WILL YOU DO? This Photo by Unknown Author is licensed under CC BY-SA GREGORY M. SMITH Former Assistant Director, Clark County District Attorney’s Office (Las Vegas) Former Chief of Staff, Nevada Office of the Attorney General Former Chief of Investigations 17 years law enforcement officer MA & BA Criminal Justice - UNLV Current CFO, CEO, BOM – Capricorn Consulting, LLC !!! MONEY + EXES + KIDS + GOVERNMENT BUREACRACY + LIFE RECIPE FOR DISASTER CLARK COUNTY D.A.’S OFFICE - FAMILY SUPPORT DIVISION Employees – 350 Vendors and clients daily – 250 Three buildings Approximately 100,000 square feet HISTORY 1966 University of Texas - one sniper in the clock tower (17 victims) Texas Monthly reporter wrote “the shooting ushered in the notion that any group of people, anywhere - even walking around a university campus on a summer day – could be killed at a random by a stranger.” In the 50 years before the University Texas shooting there were 25 public mass shootings in which four or more people died. PUBLIC MASS SHOOTINGS For the purpose of this presentation: 154 shootings 4 or more people killed by one or two shooters They occur without warning Generally occur in mundane places Victims are chosen not for what they did, but for where they are January 1, 2018 – August 30, 2018 Mass shooting deaths – 40 Other gun-related deaths – 7075 Source: Washington Post SINCE 1966 – OF THE 154 SHOOTINGS Victims ages ranged 1102 Victims killed 298 guns Source: Washington from: 185 were found Post unborn – children and -

Mass Murder and Spree Murder

Two Mass Murder and Spree Murder Two Types of Multicides A convicted killer recently paroled from prison in Tennessee has been charged with the murder of six people, including his brother, Cecil Dotson, three other adults, and two children. The police have arrested Jessie Dotson, age 33. The killings, which occurred in Memphis, Tennessee, occurred in February 2008. There is no reason known at this time for the murders. (Courier-Journal, March 9, 2008, p. A-3) A young teenager’s boyfriend killed her mother and two brothers, ages 8 and 13. Arraigned on murder charges in Texas were the girl, a juvenile, her 19-year-old boyfriend, Charlie James Wilkinson, and two others on three charges of capital murder. The girl’s father was shot five times but survived. The reason for the murders? The parents did not want their daughter dating Wilkinson. (Wolfson, 2008) Introduction There is a great deal of misunderstanding about the three types of multi- cide: serial murder, mass murder, and spree murder. This chapter will list the traits and characteristics of these three types of killers, as well as the traits and characteristics of the killings themselves. 15 16 SERIAL MURDER Recently, a school shooting occurred in Colorado. Various news outlets erroneously reported the shooting as a spree killing. Last year in Nevada, a man entered a courtroom and killed three people. This, too, was erro- neously reported as a spree killing. Both should have been labeled instead as mass murder. The assigned labels by the media have little to do with motivations and anticipated gains in the original effort to label it some type of multicide. -

Allergy Symptoms Similar to COVID Prince Philip and DMX Dead One Dead After Shooting at Mall

Tuesday, April 20, 2021 | Volume 162, Issue 27 Nebraska’s Oldest College Newspaper the doane Seeking the Truth Without Favor owl Doane’s Baseball team wins five out of six games. See Page 9 for more. One dead after shooting at mall at CHI Health Bergan (KETV). The 18-year-old Two suspects Mercy Hospital. Ja’Keya will be tried for accessory Veland, 22, was injured to homicide and has no taken into but is expected to survive. bail at this time. Two people have Westroads Mall has been arrested in connec- been the location for sev- custody after tion with the shooting, eral shootings in the past, a 16-year-old and an with one in the past year 18-year-old. Police be- on March 12 that left an shooting lieve this shooting was an officer injured. isolated incident, but they Anyone with informa- do not believe that it was tion about the shooting is a random attack. encouraged to contact the ABRIANNA MILLER The two suspects fled Omaha Police Depart- Editor-in-Chief the mall shortly after fir- ment (OPD) Homicide ing, but they were soon Unit at 402-444-5656 or apprehended by the po- Omaha Crime Stoppers On April 17, there was lice after receiving several at 402-444-STOP. Tips a shooting at the We- reports from citizens in can be submitted online stroads Mall in Omaha, the area. at omahacrimestoppers. Nebr., around noon that Douglas County Attor- org or on the P3 Tips mo- left one person dead. ney Don Kleine said that bile app. -

Creighton's Campus Plan Blooms

Creighton’s Campus Plan Blooms Welcome to the No Dispute: Werner Institute Vaccine Wars: New Graduate Programs Harper Center Fills Major Role Public Health vs. Private Fears at Creighton Fall 2008 Fall 2008 View the magazine online at: www.creightonmagazine.org University Magazine Welcome to the Harper Center .......................................8 The new Mike and Josie Harper Center for Student Life and Learning opened to students for the first time this fall. The 245,000-square-foot facility serves as Creighton’s new front door and is a dramatic anchor to Creighton’s east-campus expansion efforts. No Dispute .......................................................................16 Creighton University’s Werner Institute for Negotiation and Dispute Resolution has 8 earned national and worldwide acclaim just three years after its official launch. Learn more about the Werner Institute and how it is preparing future leaders for the rapidly expanding profession of conflict resolution. Vaccine Wars: Private Health vs. Public Fears ................20 Fears of possible negative side effects are prompting some segments of the American public not to vaccinate their children, leaving some public health professionals worried about a resurgence of deadly diseases. Creighton experts Archana Chatterjee, M.D., and 16 Linda Ohri, Pharm.D., help separate scientific fact from fiction. New Graduate Programs at Creighton .........................24 A growing number of students — especially adults and working professionals — are plugging into Creighton from work, home or an Internet café, as the newest online offerings opened in the Graduate School this fall. These new programs also cross traditional disciplinary lines, providing students with an array of professional skills that are highly sought in today’s tightening economy. -

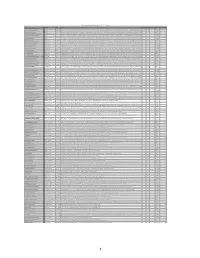

Mother Jones Mass Shootings Database

Mother Jones - Mass Shootings Database, 1982 - 2019 - Sheet1 case location date summary fatalities injured total_victims location age_of_shooter Dayton entertainment district shooting Dayton, OH 8/4/19 Connor Betts, 24, died during the attack, following a swift police response. He wore tactical gear including body armor and hearing protection, and had an ammunition device capable of holding 100 rounds. Betts had a history of threatening9 behavior27 dating 36backOther to high school, including reportedly24 having hit lists targeting classmates for rape and murder. El Paso Walmart mass shooting El Paso, TX 8/3/19 Patrick Crusius, 21, who was apprehended by police, posted a so-called manifesto online shortly before the attack espousing ideas of violent white nationalism and hatred of immigrants. "This attack is a response to the Hispanic invasion22 of Texas,"26 he allegedly48 Workplacewrote in the document. 21 Gilroy garlic festival shooting Gilroy, CA 7/28/19 Santino William LeGan, 19, fired indiscriminately into the crowd near a concert stage at the festival. He used an AK-47-style rifle, purchased legally in Nevada three weeks earlier. After apparently pausing to reload, he fired additional multiple3 rounds12 before police15 Other shot him and then he killed19 himself. A witness described overhearing someone shout at LeGan, "Why are you doing this?" LeGan, who wore camouflage and tactical gear, replied: “Because I'm really angry." The murdered victims included a 13-year-old girl, a man in his 20s, and six-year-old Stephen Romero. Virginia Beach municipal building shooting Virginia Beach, VA 5/31/19 DeWayne Craddock, 40, a municipal city worker wielding handguns, a suppressor and high-capacity magazines, killed en masse inside a Virginia Beach muncipal building late in the day on a Friday, before dying in a prolonged gun battle12 with police.4 Craddock16 reportedlyWorkplace had submitted his40 resignation from his job that morning. -

2013 VISITORS GUIDE Visitomaha.Com Omaha’Somaha’S Favoritefavorite Flavor.Flavor

TM Welcome to the Weekend 2013 VISITORS GUIDE VisitOmaha.com Omaha’sOmaha’s favoritefavorite flavor.flavor. Forks-down.Forks-down. Hand-cut Omaha Steaks™ Pasta and fresh seafood entrees Award-winning, handcrafted Great sandwiches, salads beers and root beer and soups A wide variety of appetizers Extensive wine list ONE MUSEUM. SO MANY POSSIBILITIES. Built in 1931 by Union Paci c, this rst-of-its-kind art deco train station was an architectural showpiece. Today, this rare jewel has been transformed top to bottom into one of the country’s most vibrant and beautiful hands-on museums. Come explore Omaha’s history, discover something new in the world-class temporary exhibits, and remember the past through special collections and programs. The Durham Museum is proud to be an af liate of the Smithsonian Institution and partner with the Library of Congress, the National Archives and the Field Museum. 801 South 10th Street | Omaha, NE 68108 (402) 444-5071 | www.DurhamMuseum.org REMARKABLE HOSPITALITY. INCREDIBLE CUISINE. LOCAL PASSION. PRIVATE DINING ACCOMMODATIONS FOR UP TO 70 LUNCH & DINNER • HAPPY HOUR • LIVE MUSIC NIGHTLY HAND-CUT AGED STEAKS • FRESH SEAFOOD 222 S. 15th Street, Omaha, NE 68102 RESERVATIONS 402.342.0077 [email protected] WWW . SULLIVANSSTEAKHOUSE . COM CHASE THE TRIPLE-A AFFILIATE Sheraton omaha hotel offerS acceSS to the beSt of it all. Located adjacent to I-680 in the heart of Omaha, just minutes away from all of Omaha’s best attractions. The Sheraton Omaha Hotel is dedicated to Consistency, Comfort, Cleanliness, Commitment, Class, Community, Recognition, Respect, Rewards, Safety, Security, and Unparalleled Guest Service. -

North Omaha History Timeline by Adam Fletcher Sasse

North Omaha History Timeline A Supplement to the North Omaha History Volumes 1, 2 & 3 including People, Organizations, Places, Businesses and Events from the pre-1800s to Present. © 2017 Adam Fletcher Sasse North Omaha History northomahahistory.com CommonAction Publishing Olympia, Washington North Omaha History Timeline: A Supplement to the North Omaha History Volumes 1, 2 & 3 including People, Organizations, Places, Businesses and Events from the pre-1800s to present. © 2017 Adam Fletcher Sasse CommonAction Publishing PO Box 6185 Olympia, WA 98507-6185 USA commonaction.org (360) 489-9680 To request permission to reproduce information from this publication, please visit adamfletcher.net All rights reserved; no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without prior written permission of the author, or a license permitting restricted copying issued in the United States by the author. The material presented in this publication is provided for information purposes only. This book is sold with the understanding that no one involved in this publication is attempting herein to provide professional advice. First Printing Printed in the United States Interior design by Adam Fletcher Sasse. This is for all my friends, allies, supporters and advocates who are building, nurturing, growing and sustaining the movement for historical preservation and development in North Omaha today. North Omaha History Timeline Introduction and Acknowledgments This work is intended as a supplement to the North Omaha History: Volumes 1, 2 and 3 that I completed in December 2016. These three books contain almost 900-pages of content covering more than 200 years history of the part of Omaha north of Dodge Street and east of 72nd Street. -

Local Television Coverage of a Mall Shooting

University of Nebraska at Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Communication Faculty Publications School of Communication 12-2011 Local Television Coverage of a Mall Shooting: Separating Facts From Fiction in Breaking News Jeremy Harris Lipschultz University of Nebraska at Omaha, [email protected] Michael L. Hilt University of Nebraska at Omaha, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/commfacpub Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Lipschultz, Jeremy Harris and Hilt, Michael L., "Local Television Coverage of a Mall Shooting: Separating Facts From Fiction in Breaking News" (2011). Communication Faculty Publications. 57. https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/commfacpub/57 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Communication at DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Local Television Coverage of a Mall Shooting: Separating Facts From Fiction in Breaking News Jeremy Harris Lipschultz1 and Michael L. Hilt1 ______________________________________________ 1 School of Communication, University of Nebraska at Omaha Corresponding Author: Jeremy Harris Lipschultz, School of Communication, University of Nebraska at Omaha, Arts and Sciences Hall 140, Omaha, Nebraska 68182-0112 Email: [email protected] Abstract: Local TV news emphasizes the earliest stage of crimes because “breaking news” is fresh, dramatic and visual. A qualitative analysis was conducted using a comprehensive set of recordings of the first three-and-a-half hours of local television news coverage in Omaha, Nebraska. This study identified a series of ongoing issues that have important implications for newsroom decision-makers. -

Mass Shootings in the United States: an Exploratory Study of the Trends

Mass Shootings in the United States: An Exploratory Study of the Trends from 1982- 2012 A Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at George Mason University by Luke Dillon Bachelor of Science Kutztown University, 2010 Chairman: Christopher Koper, Associate Professor Department of Criminology, Law and Society Fall Semester 2013 George Mason University Fairfax, VA Copyright 2013 Luke J. Dillon ii DEDICATION This is dedicated to my loving fiancé Abby, my two amazingly supportive parents Jim and Sandy, and my dogs Moxie and Griffin who are always helpful distractions. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express gratitude to my thesis chair, Dr. Christopher Koper, for serving as a helpful mentor and providing me with his wealth of experience towards this topic. I am also deeply grateful to my thesis committee members, Dr. Cynthia Lum and Dr. James Willis who provided keen insights into turning a rough work into a finely tuned project. Their assistance through being a committee member, but even more significantly, a teacher has helped me grow as a scholar. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Page List of Tables .................................................................................................................... vii List of Figures .................................................................................................................. viii Abstract .............................................................................................................................. ix Introduction -

Active Shooter Event Severity, Media Reporting, Offender Age and Location Philip Joshua Swift Walden University

Walden University ScholarWorks Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection 2017 Active Shooter Event Severity, Media Reporting, Offender Age and Location Philip Joshua Swift Walden University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations Part of the Communication Commons, Interactive Arts Commons, and the Public Policy Commons This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection at ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Walden University College of Social and Behavioral Sciences This is to certify that the doctoral dissertation by Philip Swift has been found to be complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the review committee have been made. Review Committee Dr. Jonathan Cabiria, Committee Chairperson, Psychology Faculty Dr. James Herndon, Committee Member, Psychology Faculty Dr. Stephen Rice, University Reviewer, Psychology Faculty Chief Academic Officer Eric Riedel, Ph.D. Walden University 2017 Active Shooter Event Severity, Media Reporting, Offender Age and Location by Philip J. Swift MS, Forensic Psychology, Walden University, 2013 MBA, American Intercontinental University, 2006 MBA, American Intercontinental University, 2005 BS, Criminal Justice, American Intercontinental University, 2005 Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Forensic Psychology Walden University February 2017 Abstract Following the 1999 Columbine High School shooting, it was hypothesized that offenders used knowledge gained from news media reports about previous events to plan mass shootings. -

Congressional Record—House H2242

H2242 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — HOUSE February 27, 2019 military, I believe the need is clear and BACKGROUND CHECK BILL GUN VIOLENCE PREVENTION pressing, the law supports immediate (Mr. MICHAEL F. DOYLE of Penn- (Ms. SCHAKOWSKY asked and was action, and ample funding exists to ad- sylvania asked and was given permis- given permission to address the House dress this crisis. sion to address the House for 1 minute.) for 1 minute.) f Mr. MICHAEL F. DOYLE of Pennsyl- Ms. SCHAKOWSKY. Mr. Speaker, I vania. Mr. Speaker, more than 500 am so proud to stand here today as we b 1215 Pennsylvanians are murdered with work to pass gun violence prevention legislation. BACKGROUND CHECKS WORK guns each year, causing untold suf- fering and tearing our communities I would like to share a letter from a (Mrs. DAVIS of California asked and apart. Pennsylvanians are crying out fifth grader constituent of mine, Alex, was given permission to address the for commonsense legislation to stop from Northfield, Illinois, that perfectly House for 1 minute.) the bloodshed, legislation like H.R. 8, explains why we must pass H.R. 8 and Mrs. DAVIS of California. Mr. Speak- the bill before us today. H.R. 1112. Alex writes: ‘‘I don’t want to see in- er, today is a momentous day, one that Now, nobody thinks that universal nocent people dying for no reason. I makes me proud of this Chamber. After background checks would eliminate want all children to feel safe at school. years of inaction, Congress is moving gun violence, but the facts suggest that I want all adults to feel safe at work. -

1 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT of CONNECTICUT JUNE SHEW, Et Al. : No. 3:13-CV-0739 (AVC) Plaintiffs, : : V.

Case 3:13-cv-00739-AVC Document 81 Filed 10/11/13 Page 1 of 5 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT OF CONNECTICUT JUNE SHEW, et al. : No. 3:13-CV-0739 (AVC) Plaintiffs, : : v. : : DANNEL P. MALLOY, et al. : Defendants. : OCTOBER 11, 2013 DEFENDANTS’ EXHIBIT LIST Exhibit 1 - Public Act 13-3 Exhibit 2 - Public Act 13-220 Exhibit 3 - Public Act 93-306 Exhibit 4 - Public Act 01-130 Exhibit 5 - Excerpts from Senate Debates on Public Act 13-3 Exhibit 6 - Excerpts from Senate Debates on Public Act 93-360 Exhibit 7 - Governor’s Sandy Hook Advisory Commissioner Interim Report Exhibit 8 - Governor’s Legislative Proposals Exhibit 9 - Federal ban (1994) Exhibit 10 - Delehanty Affidavit Exhibit 11 - Delehanty Affidavit – Photos of gun engravings Exhibit 12 - Delehanty Affidavit – Picture of tubular magazine Exhibit 13 - Delehanty Affidavit – Excerpts from Gun Digest Exhibit 14 - Mattson Affidavit Exhibit 15 – DESPP Form DPS-3-C 1 Case 3:13-cv-00739-AVC Document 81 Filed 10/11/13 Page 2 of 5 Exhibit 16 - Cooke Affidavit Exhibit 17 - ATF Study (July 1989) Exhibit 18 - ATF Profile (April 1994) Exhibit 19 - ATF Study (April 1998) Exhibit 20 - ATF Study (January 2011) Exhibit 21 - H.R. Rep. 103-489 (1994) Exhibit 22 - Excerpts from LCAV Comparative Evaluation Exhibit 23 - Rovella Affidavit Exhibit 24 - Hartford Gun Seizure Data Exhibit 25 - Hartford 2012 End of Year Statistics Exhibit 26 - Koper Affidavit Exhibit 27 - Koper Curriculm Vitae Exhibit 28 - Impact Evaluation of the Public Safety and Recreational Firearms Use Protection Act of 1994: Final Report. The Urban Institute, March 13, 1997 (“Koper 1997”) Exhibit 29 - Updated Assessment of the Federal Assault Weapons Ban: Impacts on Gun Markets and Gun Violence, 1994-2003, Christopher S.