Cattle Bulls, Baiting & Hard Cheese

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Isle of Wight Coast Path Guided Trail Holiday

The Isle of Wight Coast Path Guided Trail Holiday Tour Style: Guided Trails Destinations: Isle of Wight & England Trip code: FWLIC Trip Walking Grade: 3 HOLIDAY OVERVIEW The Isle of Wight Coast Path circuits the island in an anti-clockwise direction and provides a wonderful opportunity to view the island’s beautiful and varied coastline, including the chalk headlands of the Needles and Culver Cliff. The trail is interspersed with pretty coastal villages and Victorian resorts such as Ventnor. It includes some inland walking around Queen Victoria’s Osborne Estate, Cowes and Newtown Harbour National Nature Reserve. WHAT'S INCLUDED • High quality en-suite accommodation in our country house • Full board from dinner upon arrival to breakfast on departure day • The services of an HF Holidays' walks leader • All transport on walking days www.hfholidays.co.uk PAGE 1 [email protected] Tel: +44(0) 20 3974 8865 HOLIDAYS HIGHLIGHTS • A circuit of the Isle of Wight coast • The dramatic chalk headlands of the Needles and Culver Cliff • Stay at Freshwater Bay House TRIP SUITABILITY This Guided Walking/Hiking Trail is graded 3 which involves walks/hikes on generally good paths, but with some long walking days. There may be some sections over rough or steep terrain and will require a good level of fitness as you will be walking every day. It is your responsibility to ensure you have the relevant fitness required to join this holiday. Fitness We want you to be confident that you can meet the demands of each walking day and get the most out of your holiday. -

Historic Environment Action Plan West Wight Chalk Downland

Directorate of Community Services Director Sarah Mitchell Historic Environment Action Plan West Wight Chalk Downland Isle of Wight County Archaeology and Historic Environment Service October 2008 01983 823810 archaeology @iow.gov.uk Iwight.com HEAP for West Wight Chalk Downland. INTRODUCTION The West Wight Chalk Downland HEAP Area has been defined on the basis of geology, topography and historic landscape character. It forms the western half of a central chalk ridge that crosses the Isle of Wight, the eastern half having been defined as the East Wight Chalk Ridge . Another block of Chalk and Upper Greensand in the south of the Isle of Wight has been defined as the South Wight Downland . Obviously there are many similarities between these three HEAP Areas. However, each of the Areas occupies a particular geographical location and has a distinctive historic landscape character. This document identifies essential characteristics of the West Wight Chalk Downland . These include the large extent of unimproved chalk grassland, great time-depth, many archaeological features and historic settlement in the Bowcombe Valley. The Area is valued for its open access, its landscape and wide views and as a tranquil recreational area. Most of the land at the western end of this Area, from the Needles to Mottistone Down, is open access land belonging to the National Trust. Significant historic landscape features within this Area are identified within this document. The condition of these features and forces for change in the landscape are considered. Management issues are discussed and actions particularly relevant to this Area are identified from those listed in the Isle of Wight HEAP Aims, Objectives and Actions. -

Neolithic & Early Bronze Age Isle of Wight

Neolithic to Early Bronze Age Resource Assessment The Isle of Wight Ruth Waller, Isle of Wight County Archaeology and Historic Environment Service September 2006 Inheritance: The map of Mesolithic finds on the Isle of Wight shows concentrations of activity in the major river valleys as well two clusters on the north coast around the Newtown Estuary and Wooton to Quarr beaches. Although the latter is likely due to the results of a long term research project, it nevertheless shows an interaction with the river valleys and coastal areas best suited for occupation in the Mesolithic period. In the last synthesis of Neolithic evidence (Basford 1980), it was claimed that Neolithic activity appears to follow the same pattern along the three major rivers with the Western Yar activity centred in an area around the chalk gap, flint scatters along the River Medina and greensand activity along the Eastern Yar. The map of Neolithic activity today shows a much more widely dispersed pattern with clear concentrations around the river valleys, but with clusters of activity around the mouths of the four northern estuaries and along the south coast. As most of the Bronze Age remains recorded on the SMR are not securely dated, it has been difficult to divide the Early from the Late Bronze Age remains. All burial barrows and findspots have been included within this period assessment rather than the Later Bronze Age assessment. Nature of the evidence base: 235 Neolithic records on the County SMR with 202 of these being artefacts, including 77 flint or stone polished axes and four sites at which pottery has been recovered. -

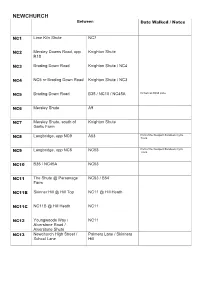

NEWCHURCH Between Date Walked / Notes

NEWCHURCH Between Date Walked / Notes NC1 Lime Kiln Shute NC7 NC2 Mersley Downs Road, opp Knighton Shute R18 NC3 Brading Down Road Knighton Shute / NC4 NC4 NC5 nr Brading Down Road Knighton Shute / NC3 NC5 Brading Down Road B35 / NC10 / NC45A Known as Blind Lane NC6 Mersley Shute A9 NC7 Mersley Shute, south of Knighton Shute Garlic Farm Langbridge, opp NC9 A53 Part of the Newport-Sandown Cycle NC8 Track Langbridge, opp NC8 NC53 Part of the Newport-Sandown Cycle NC9 Track NC10 B35 / NC45A NC53 NC11 The Shute @ Parsonage NC53 / B54 Farm NC11B Skinner Hill @ Hill Top NC11 @ Hill Heath NC11C NC11B @ Hill Heath NC11 NC12 Youngwoods Way / NC11 Alverstone Road / Alverstone Shute NC13 Newchurch High Street / Palmers Lane / Skinners School Lane Hill NC14 Palmers Lane Dyers Lane Path obstructed not walkable NC15 Skinners Hill Alverstone Road NC16 Winford Road Alverstone Road NC17 Alverstone Main Road, opp Burnthouse Lane / NC44 Alverstone squirrel hide NC42 / youngwoods Way NC18 Burnthouse Lane / NC44 SS48 NC19 Alverstone Road NC20 / NC21 NC20 Alverstone Road / SS54 @ Cheverton Farm Borthwood Copse Borthwood Lane campsite NC21 Alverstone Road NC19 / NC20 / NC21 NC22 Borthwood Lane, opp NC19 NC22A @ Embassy Way Sandown airport @ Beaulieu Cottages runway ________________ SS30 @ Scotchells Brook SS28 @ Sandown Air Port NC22A NC22 / NC22B @ Embassy NC22 / SS25 Way Scotchells Brook Lane / NC22 / NC22A Known as Embassy Way – Sandown NC22B airport NC23 @ Embassy Way NC23 Borthwood Lane, opp Scotchells Brook Lane / SS57 NC24 Hale Common (A3056) @ Winford -

Coastal Processes Review

Water and Environment Management Framework Lot 3 – Engineering and Related Services West Wight Coastal Flood and Erosion Risk Management Strategy Appendix C - Coastal Processes and Geotechnics Summary August 2015 Document overview Capita | AECOM was commissioned by the Isle of Wight Council in October 2014 to undertake a Coastal Flood and Erosion Risk Management Strategy. As part of this commission, a brief review of coastal processes and geotechnics has been undertaken to inform the option development phase of the Strategy. Document history Version Status Issue date Prepared by Reviewed by Approved by George Batt – Assistant Coastal Jonathan Short Engineer Tara-Leigh Draft for – 1 30th March 2015 Jason McVey – comment Senior Coastal Drummond – Associate Specialist Principal Flood and Coastal Specialist George Batt – Assistant Coastal Updated Jonathan Short Engineer Tara-Leigh following – 2 4th August 2015 Jason McVey – client Senior Coastal Drummond – Associate comments Specialist Principal Flood and Coastal Specialist Scott House, Alencon Link, Basingstoke, Hampshire, RG21 7PP. i Limitations Capita Property and Infrastructure Ltd (“Capita”) | URS Infrastructure & Environment UK Limited (“AECOM”) has prepared this Report for the sole use of the Isle of Wight Council in accordance with the Agreement under which our services were performed. No other warranty, expressed or implied, is made as to the professional advice included in this Report or any other services provided by Capita | AECOM. This Report is confidential and may not be disclosed by the Client nor relied upon by any other party without the prior and express written agreement of Capita | AECOM. The conclusions and recommendations contained in this Report are based upon information provided by others and upon the assumption that all relevant information has been provided by those parties from whom it has been requested and that such information is accurate. -

WALKING EXPERIENCES: TOP of the WIGHT Experience Sustainable Transport

BE A WALKING EXPERIENCES: TOP OF THE WIGHT Experience sustainable transport Portsmouth To Southampton s y s rr Southsea Fe y Cowe rr Cowe Fe East on - ssenger on - Pa / e assenger l ampt P c h hi Southampt Ve out S THE EGYPT POINT OLD CASTLE POINT e ft SOLENT yd R GURNARD BAY Cowes e 5 East Cowes y Gurnard 3 3 2 rr tsmouth - B OSBORNE BAY ishbournFe de r Lymington F enger Hovercra Ry y s nger Po rr as sse Fe P rtsmouth/Pa - Po e hicl Ve rtsmouth - ssenger Po Rew Street Pa T THORNESS AS BAY CO RIVE E RYDE AG K R E PIER HEAD ERIT M E Whippingham E H RYDE DINA N C R Ve L Northwood O ESPLANADE A 3 0 2 1 ymington - TT PUCKPOOL hic NEWTOWN BAY OO POINT W Fishbourne l Marks A 3 e /P Corner T 0 DODNOR a 2 0 A 3 0 5 4 Ryde ssenger AS CREEK & DICKSONS Binstead Ya CO Quarr Hill RYDE COPSE ST JOHN’S ROAD rmouth Wootton Spring Vale G E R CLA ME RK I N Bridge TA IVE HERSEY RESERVE, Fe R Seaview LAKE WOOTTON SEAVIEW DUVER rr ERI Porcheld FIRESTONE y H SEAGR OVE BAY OWN Wootton COPSE Hamstead PARKHURST Common WT FOREST NE Newtown Parkhurst Nettlestone P SMALLBROOK B 4 3 3 JUNCTION PRIORY BAY NINGWOOD 0 SCONCE BRIDDLESFORD Havenstreet COMMON P COPSES POINT SWANPOND N ODE’S POINT BOULDNOR Cranmore Newtown deserted HAVENSTREET COPSE P COPSE Medieval village P P A 3 0 5 4 Norton Bouldnor Ashey A St Helens P Yarmouth Shaleet 3 BEMBRIDGE Cli End 0 Ningwood Newport IL 5 A 5 POINT R TR LL B 3 3 3 0 YA ASHEY E A 3 0 5 4Norton W Thorley Thorley Street Carisbrooke SHIDE N Green MILL COPSE NU CHALK PIT B 3 3 9 COL WELL BAY FRES R Bembridge B 3 4 0 R I V E R 0 1 -

Isle of Wight Rivers

KENT AREA HAMPSHIRE Maidstone AREA Winchester Worthing SUSSEX AREA Area Administrative Boundaries Regional Boundary Area Office Rivers of Regional Headquarters the Isle ENVIRONMENT AGENCY GENERAL ENQUIRY LINE of Wight 0845 933 3111 ENVIRONMENT AGENCY FLOODLINE 0845 988 1188 ENVIRONMENT AGENCY EMERGENCY HOTLINE 0800 80 70 60 FACT FILES 9 Rivers of the Isle of Wight Environment Agency - a better organisation works for the public and environment in England and Wales has specific duties and powers. Lymington Cowes R i East v e The Solent r Cowes for present and future generations. M e The Solent d i n Nationally, around 15 million hectares a Fishbourne ek re Milford- Wootton C Northwood n The Environment Agency is one of the of land are managed by the Agency k o Newtown River t on-Sea o t o o r o B s W ' r world's most powerful environmental along with 36,000km of rivers and e Nettlestone n R e m o l d B v a a g l H e B P a ck Ryde Yarmouth rn ro b e o rid t k g watchdogs, regulating air, land and 5,000km of coastline, including more es e W Bro o Th k St Helens Bembridge o rl water. As 'guardians of the than 2 million hectares of coastal ey Br o Yar o e k n rn r u environment' the Agency has legal waters. Totland ste Bo Newport e l r u a W Y Ca Brading n er st duties to protect and improve the Freshwater Ea There are eight regional offices, which R i r a v Y environment throughout England and e r n r M e t are split into 26 area offices. -

BULLETIN Aug 2008

August 2008 Issue no. 50 Bulletin Established 1919 www.iwnhas.org Contents Page(s) Page(s) President`s Address 1 In Praise of Ivy 8-11 Notice Board 2 Note from 1923 Proceedings 11 Country Notes 3-4 General Meetings 12-20 Undercliff Walls Survey 4-5 Section Meetings 20-30 Society Library 5 Membership Secretaries` Notes 31 Andy`s Notes 5-6 Megalith Monuments 6-8 An Unusual Moth 8 President's Address On a recent visit to the Society's Headquarters at Ventnor I was handed a piece of paper outlin- ing the duties of the President. One clause seemed directly written to me - the President was “not ex- pected to be expert in all the fields covered by the various sections." As most of you will know, unlike past Presidents who have been specialists, I am very much an ordinary member with a general interest in natural history and archaeology, but my membership over many years has widened my knowledge and kept up a spirit of inquiry. With this in mind last May I joined the general meeting exploring the ground around the glass- houses of Wight Salads, somewhere completely new to me. It proved to be two hours of continuous in- terest as we wandered by the new lakes created from the water used in the hydroponic growing system. With experts in identifying grasses, mosses, flowers, birds all to hand, and all more than willing to point out, identify and explain when I asked any question. It was a real illustration of teaching and learning in the best way. -

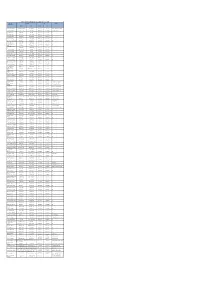

ROAD OR PATH NAME from to from to Forest Road, Newport

ROAD AND PATH CLOSURES (10th August 2020 ‐ 16th August 2020) ROAD OR LOCATION DATE DETAILS PATH NAME FROM TO FROM TO Forest Road, Newport Hampshire Crescent Medina Way 14.08.2020 23.08.2020 Junction improvement works Chine Avenue, Shanklin Everton Lane High Street 14.08.2020 17.08.2020 Carriageway repairs High Street, Cowes Carvel Lane Sun Hill 14.08.2020 25.09.2020 CIP Town Quay, Cowes Entire length Entire length 14.08.2020 25.09.2020 CIP High Street, Brading Entire length Entire length 14.08.2020 25.09.2020 CIP Quay Lane, Brading Entire length Entire length 14.08.2020 25.09.2020 CIP Seaview Lane, Nettlestone Entire length Entire length 14.08.2020 25.09.2020 CIP Surbiton Road, Ryde Entire length Entire length 14.08.2020 25.09.2020 CIP Upper Highland Road, Entire length Entire length 14.08.2020 25.09.2020 CIP Ryde Lower Highland Road, Entire length Entire length 14.08.2020 25.09.2020 CIP Ryde Lower Road, Brading Golf Links Road The Mall 14.08.2020 25.09.2020 CIP Upper Road, Brading Main Road Bullys Hill 14.08.2020 25.09.2020 CIP Zig Zag Road, Ventnor Entire length Entire length 14.08.2020 25.09.2020 CIP Bellevue Road, Ventnor Entire length Entire length 14.08.2020 25.09.2020 CIP Terrace Road, Newport Entire length Entire length 14.08.2020 25.09.2020 CIP Trafalgar Road, Newport Union Street New Street 14.08.2020 25.09.2020 CIP Bignor Place, Newport Entire length Entire length 14.08.2020 25.09.2020 CIP Clarence Road, Newport Entire length Entire length 14.08.2020 25.09.2020 CIP York Road, Newport Entire length Entire length 14.08.2020 25.09.2020 -

Heritage Coast Leaflet

seo ih OBPartnership AONB Wight of Isle Hamstead Tennyson & ɀ The wildlife reflects the tranquil nature of the landscape – the wildlife and habitats that thrive Hamstead here are susceptible to disturbance, please respect this – please stay on the paths and avoid lighting fires or barbeques. Heritage Coasts ɀ Fossils are easy to find amongst the beach gravel. Look for flat, black coloured pieces of turtle The best and most valued parts of the coastlines of shell, after you have found these start looking for England and Wales have been nationally recognised teeth and bones. through the Heritage Coast accolade. ɀ Hamstead Heritage Coast Birds such as teal, curlew, snipe and little egrets Bouldnor Cliffs CA Wooden causeway at Newtown CA feed on a diet of insects, worms and crustaceans. The Hamstead Heritage Coast is situated on the north ɀ west of the Isle of Wight running from Thorness near A home to 95 different species, suggests that life ɀ The salt marsh at Newtown is a valuable habitat Cowes to Bouldnor near Yarmouth. A tranquil and in the mud of Newtown Harbour is relatively that supports a wide range of wildlife and is also a secretive coastline with inlets, estuaries and creeks; unaffected by human activities. superb natural resource for learning. wooded hinterland and gently sloping soft cliffs, this ɀ Some of the woodland is ancient and the woods beautiful area offers a haven for wildlife including red contain a huge biodiversity with many nationally squirrels and migratory birds. The ancient town of rare species such as red squirrels. Newtown and its National Nature Reserve also fall within this area. -

Multi-Agency Flood Response Plan

NOT PROTECTIVELY MARKED Multi-Agency Flood Response Plan ANNEX 4 TECHNICAL INFORMATION Prepared By: Isle of Wight Local Authority Emergency Management Version: 1.1 Island Resilience Forum 245 Version 1.0 Multi-Agency Flood Response Plan Date: March 2011 May 2010 BLANK ____________________________________________________________________________________________ Island Resilience Forum 246 Version 1.1 Multi-Agency Flood Response Plan March 2011 Not Protectively Marked Annex 4 – Technical Information Contents ____________________________________________________________________________________________ Annex 4 – Technical Information Page Number 245 Section 1 – Weather Forecasting and Warning • Met Office 249 • Public Weather Service (PWS) 249 • National Severe Weather Warning Service (NSWWS) 250 • Recipients of Met Office Weather Warnings 255 • Met Office Storm Tide Surge Forecasting Service 255 • Environment Monitoring & Response Centre (EMARC) 256 • Hazard Manager 256 Section 2 – Flood Forecasting • Flood Forecasting Centre 257 • Flood Forecasting Centre Warnings 257 • Recipients of Flood Forecasting Centre Warnings 263 Section 3 – Flood Warning • Environment Agency 265 • Environment Agency Warnings 266 • Recipients of Environment Agency Flood Warnings 269 Section 4 – Standard Terms and Definitions • Sources/Types of Flooding 271 • Affects of Flooding 272 • Tide 273 • Wind 276 • Waves 277 • Sea Defences 279 • Forecasting 280 Section 5 – Flood Risk Information Maps • Properties at Flood Risk 281 • Areas Susceptible to Surface Water Flooding -

Historic Environment Action Plan Arreton Valley

Directorate of Community Services Director Sarah Mitchell Historic Environment Action Plan Arreton Valley Isle of Wight County Archaeology and Historic Environment Service 0198 3 823810 Archaeology Unit @iow.gov.uk Iwight.com HEAP for Arreton Valley INTRODUCTION This HEAP Area has been defined on the basis of geology, topography, land use and settlement patterns which differentiate it from other HEAP areas. This HEAP identifies essential characteristics of the Arreton Valley HEAP Area as its open and exposed landscape with few native trees, its intensive agriculture and horticulture, its historic settlement patterns and buildings, and its valley floor pastures. The most significant features of this historic landscape, the most important forces for change, and key management issues are considered. Actions particularly relevant to this Area are identified from those listed in the Isle of Wight HEAP Aims, Objectives and Actions. ANALYSIS AND ASSESSMENT Location, Geology and Topography • Geology is mainly Ferruginous Sands of the Lower Greensand Series with overlying Gravel Terraces in much of the area. Some Plateau Gravel deposits. Thin bands of Sandrock, Carstone, Gault and Upper Greensand along northern edge of area on boundary with East Wight Chalk Ridge . • Alluvium in river valleys. • Main watercourse is Eastern Yar which enters this HEAP Area at Great Budbridge and flows north east towards Newchurch. o Tributary streams flow into Yar. o The eastern side of the Yar Valley is crossed by drainage ditches to the south of Horringford. o Low-lying land to the east of Moor Farm and south of Bathingbourne has larger drainage canals • Land is generally below 50m OD with maximum altitude of 62m OD near Arreton Gore Cemetery.