Not to Be Published in the Official Reports in The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LESLIE VAN HOUTEN, ) ) Related Cases: BH007887; S230851 6 Petitioner, ) B240743; B286023 ) S45992; S238110; S221618 7 on Habeas Corpus

1 SUPERIOR COURT OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA 2 COUNTY OF LOS ANGELES 3 4 In Re ) CASE Nos. BH _________ ) 5 LESLIE VAN HOUTEN, ) ) Related Cases: BH007887; S230851 6 Petitioner, ) B240743; B286023 ) S45992; S238110; S221618 7 on Habeas Corpus. ) ______________________________ ) Superior Court Case A253156 8 9 _______________________________________________________ 10 PETITION FOR WRIT OF HABEAS CORPUS; 11 MEMORANDUM OF POINTS & AUTHORITIES 12 _______________________________________________________ 13 RICH PFEIFFER 14 State Bar No. 189416 NANCY TETRAULT 15 State Bar No. 150352 P.O. Box 721 16 Silverado, CA 92676 Telephone: (714) 710-9149 17 Email: [email protected] 18 Attorneys for Petitioner Leslie Van Houten 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 PETITION FOR WRIT OF HABEAS CORPUS Page 1 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 2 TABLE OF EXHIBITS. 2 3 INTRODUCTION. 4 4 PROCEDURAL HISTORY. 8 5 STATEMENT OF FACTS. 10 6 PETITIONER’S JANUARY 30, 2019 PAROLE HEARING DECISION. 16 7 JUNE 3, 2019 GOVERNOR REVERSAL. 17 8 MEMORANDUM OF POINTS AND AUTHORITIES.. 18 9 I. MS. VAN HOUTEN IS NOT AN UNREASONABLE RISK TO 10 PUBLIC SAFETY UNDER ANY STANDARD.. 18 11 A. THE STANDARD OF REVIEW.. 18 12 1. Governor Reversal Standard of Review.. 18 13 2. The De Novo Standard of Review is Appropriate. 22 14 B2.. THE REVERSAL OF MS. VAN HOUTEN’S FINDING OF PAROLE SUITABILITY WAS A DENIAL OF DUE PROCESS.. 25 15 II. THE GOVERNOR FORFEITED NEW REASONS TO DENY PAROLE 16 THAT WERE NOT ASSERTED AT REVERSALS OF EARLIER REVERSALS OF GRANTS OF PAROLE.. 31 17 18 III. MS. VAN HOUTEN WAS DENIED DUE PROCESS WHEN THE PROSECUTION HAD EXCULPATORY EVIDENCE IN THE CHARLES 19 “TEX” WATSON TAPES, AND FAILED TO DISCLOSE IT. -

Tropical Storm Forms in Gulf Morrow,” Eckstein Said Wednes- Andrea to Bring Torrential Rains ■ for Updates on Tropical Day Night

Fuji Asian Bistro brings taste of Far East to Southeast /C1 THURSDAY TODAY CITRUS COUNTY & next morning HIGH 83 Mostly cloudy. 80 LOW percent chance of thunderstorms 76 PAGE A4 www.chronicleonline.com JUNE 6, 2013 Florida’s Best Community Newspaper Serving Florida’s Best Community 50¢ VOL. 118 ISSUE 303 Tropical storm forms in Gulf morrow,” Eckstein said Wednes- Andrea to bring torrential rains ■ For updates on Tropical day night. “Hope nobody had any Tropical Storm Storm Andrea, check the outdoor plans.” Andrea is the first named Chronicle’s storm of the 2013 Atlantic MIKE WRIGHT casters did not expect it to Facebook page or Eckstein said some flooding the sheriff’s office blog, hurricane season. Staff writer strengthen to a hurricane. could be expected in areas prone 5:30 pm EDT, June 5. Forecasters issued a tropical citruseoc.blogspot.com. for high water, such as Ozello, La. Ga.Ala.Mis. 300 mi The young hurricane season’s storm warning for a swath of parts of Homosassa and Crystal 300 km first named storm formed Florida’s west coast starting at rain, said Capt. Joe Eckstein, who River. Eckstein also said residents Tropical Storm 30° Andrea Fla. Wednesday evening in the Gulf of Boca Grande, an island to the heads the county’s Emergency should keep an eye on the Mexico, promising a wet and northwest of Fort Myers, and end- Operations Center. 3:21 p.m. high tide in King’s Bay. Gulf of BAHAMAS windy Thursday in Citrus County ing in the Big Bend area of the Eckstein said forecasters ex- The county is not opening sand- Mexico CUBA and across the Florida west coast. -

America's Fascination with Multiple Murder

CHAPTER ONE AMERICA’S FASCINATION WITH MULTIPLE MURDER he break of dawn on November 16, 1957, heralded the start of deer hunting T season in rural Waushara County, Wisconsin. The men of Plainfield went off with their hunting rifles and knives but without any clue of what Edward Gein would do that day. Gein was known to the 647 residents of Plainfield as a quiet man who kept to himself in his aging, dilapidated farmhouse. But when the men of the vil- lage returned from hunting that evening, they learned the awful truth about their 51-year-old neighbor and the atrocities that he had ritualized within the walls of his farmhouse. The first in a series of discoveries that would disrupt the usually tranquil town occurred when Frank Worden arrived at his hardware store after hunting all day. Frank’s mother, Bernice Worden, who had been minding the store, was missing and so was Frank’s truck. But there was a pool of blood on the floor and a trail of blood leading toward the place where the truck had been garaged. The investigation of Bernice’s disappearance and possible homicide led police to the farm of Ed Gein. Because the farm had no electricity, the investigators con- ducted a slow and ominous search with flashlights, methodically scanning the barn for clues. The sheriff’s light suddenly exposed a hanging figure, apparently Mrs. Worden. As Captain Schoephoerster later described in court: Mrs. Worden had been completely dressed out like a deer with her head cut off at the shoulders. -

Pynchon's Sound of Music

Pynchon’s Sound of Music Christian Hänggi Pynchon’s Sound of Music DIAPHANES PUBLISHED WITH SUPPORT BY THE SWISS NATIONAL SCIENCE FOUNDATION 1ST EDITION ISBN 978-3-0358-0233-7 10.4472/9783035802337 DIESES WERK IST LIZENZIERT UNTER EINER CREATIVE COMMONS NAMENSNENNUNG 3.0 SCHWEIZ LIZENZ. LAYOUT AND PREPRESS: 2EDIT, ZURICH WWW.DIAPHANES.NET Contents Preface 7 Introduction 9 1 The Job of Sorting It All Out 17 A Brief Biography in Music 17 An Inventory of Pynchon’s Musical Techniques and Strategies 26 Pynchon on Record, Vol. 4 51 2 Lessons in Organology 53 The Harmonica 56 The Kazoo 79 The Saxophone 93 3 The Sounds of Societies to Come 121 The Age of Representation 127 The Age of Repetition 149 The Age of Composition 165 4 Analyzing the Pynchon Playlist 183 Conclusion 227 Appendix 231 Index of Musical Instruments 233 The Pynchon Playlist 239 Bibliography 289 Index of Musicians 309 Acknowledgments 315 Preface When I first read Gravity’s Rainbow, back in the days before I started to study literature more systematically, I noticed the nov- el’s many references to saxophones. Having played the instru- ment for, then, almost two decades, I thought that a novelist would not, could not, feature specialty instruments such as the C-melody sax if he did not play the horn himself. Once the saxophone had caught my attention, I noticed all sorts of uncommon references that seemed to confirm my hunch that Thomas Pynchon himself played the instrument: McClintic Sphere’s 4½ reed, the contra- bass sax of Against the Day, Gravity’s Rainbow’s Charlie Parker passage. -

“'The Paranoia Was Fulfilled' – an Analysis of Joan Didion's

“‘THE PARANOIA WAS FULFILLED’ – AN ANALYSIS OF JOAN DIDION’S ESSAY ‘THE WHITE ALBUM’” Rachele Colombo Independent Scholar ABSTRACT This article looks at Joan Didion’s essay “The White Album” from the collection of essays The White Album (1979), as a relevant text to reflect upon America’s turmoil in the sixties, and investigate in particular the subject of paranoia. “The White Album” represents numerous historical events from the 1960s, but the central role is played by the Manson Murders case, which the author considers it to be the sixties’ watershed. This event–along with many others–shaped Didion’s perception of that period, fueling a paranoid tendency that reflected in her writing. Didion appears to be in search of a connection between her growing anxiety and these violent events throughout the whole essay, in an attempt to understand the origin of her paranoia. Indeed, “The White Album” deals with a period in Didion’s life characterized by deep nervousness, caused mainly by her increasing inability to make sense of the events surrounding her, the Manson Murders being the most inexplicable one. Conse- quently, Didion seems to ask whether her anxiety and paranoia are justified by the numerous violent events taking place in the US during the sixties, or if she is giving a paranoid interpretation of com- pletely neutral and common events. Because of her inability to find actual connections between the events surrounding her, in particular political assassinations, Didion realizes she feels she is no longer able to fulfill her main duty as a writer: to tell a story. -

The Long Prison Journey of Leslie Van Houten: Life Beyond the Cult by Kariene Faith Boston: Northeastern University Press (2001), 216 Pp

The long Prison Journey of leslie Van Houten: life Beyond the Cult By Kariene Faith Boston: Northeastern University Press (2001), 216 pp. Reviewed by Liz Elliott n the last year of the 1960s, a decade of anomie, the U.S. experienced two I events that would symbolize different aspects of its culture into the next millennium. These events took place at opposite sides of the country, although they occun-ed less than a week apart. One event, a cultural festival of music and arts, has remained in time as an example of the possibilities of peaceful co existence in adverse circumstances oflarge numbers ofpeopJe. From August 15th to the 17th the Woodstock Music and Arts Festival's patrons endured rain and mud - and all of the other inconveniences that would reasonably accrue in a situation where unexpected large numbers ofpeople converged in one location -to see some of the decade's masters of rock and roll and folk music perfonn in the state of New York. Almost half a million people, many of whom were experiencing the event under the influence of various illicit drugs, attended Woodstock and lived together peacefhlly for one weekend. 1 Across the continent a few days earlier, the world heard the news of two ten-ible sets of murders in California that shook the sense of security that until then was enjoyed by Americans. We were soon to learn that these bizarre, seemingly ritualistic killings were the bidding of a charismatic but crazy man who was state-raised2 and resourceful. In this case the drugs were used to weaken the already fragile resolve ofyoung idealistic people who were searching for themselves and open to new ways of seeing the world. -

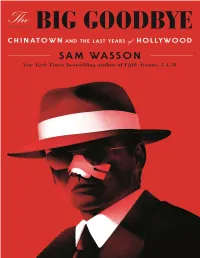

The Big Goodbye

Robert Towne, Edward Taylor, Jack Nicholson. Los Angeles, mid- 1950s. Begin Reading Table of Contents About the Author Copyright Page Thank you for buying this Flatiron Books ebook. To receive special offers, bonus content, and info on new releases and other great reads, sign up for our newsletters. Or visit us online at us.macmillan.com/newslettersignup For email updates on the author, click here. The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy. For Lynne Littman and Brandon Millan We still have dreams, but we know now that most of them will come to nothing. And we also most fortunately know that it really doesn’t matter. —Raymond Chandler, letter to Charles Morton, October 9, 1950 Introduction: First Goodbyes Jack Nicholson, a boy, could never forget sitting at the bar with John J. Nicholson, Jack’s namesake and maybe even his father, a soft little dapper Irishman in glasses. He kept neatly combed what was left of his red hair and had long ago separated from Jack’s mother, their high school romance gone the way of any available drink. They told Jack that John had once been a great ballplayer and that he decorated store windows, all five Steinbachs in Asbury Park, though the only place Jack ever saw this man was in the bar, day-drinking apricot brandy and Hennessy, shot after shot, quietly waiting for the mercy to kick in. -

Will You Die for Me? by Charles Watson As Told to Chaplain Ray Hoekstra Copyright

Will You Die For Me? by Charles Watson as told to Chaplain Ray Hoekstra Copyright...................................................................................... 1 Acknowledgments ........................................................................2 Dedication ....................................................................................2 About the Author .........................................................................3 Sure, Charlie, You Can Kill Me ...................................................4 Behold, He Is In The Desert ........................................................8 The Campus Kid........................................................................ 14 The Times, They Are A-Changin' .............................................18 California Dreamin' ...................................................................23 Gentle Children, With Flowers In Their Hair ...........................27 Family .........................................................................................33 Magical Mystery Tour ................................................................37 Watershed: The White Album ...................................................42 Happy in Hollywood ..................................................................48 Revolution / Revelation .............................................................51 Piggies .........................................................................................57 You Were Only Waiting for This Moment .................................62 -

Volume 6 Number 064 the Manson Murders

Volume 6 Number 064 The Manson Murders – I Lead: Of the turbulent events that marked the decade of the 1960s, the chilling and notorious Charles Manson murders are clearly among most shocking. Intro.: A Moment in Time with Dan Roberts. Content: Charles Manson was born in 1934. He had an unstable childhood and by the age of thirteen was ripening into young man with a decidedly criminal inclination. After being released from a California prison in 1967, he moved to San Francisco, where he began attracting a group of devoted young people who would eventually follow him on a path of violence and destruction. Playing upon sections of the Book of Revelation and drawing inspiration from certain Beatle songs, Manson and his followers began preparing for a racial war in which black and white would annihilate each other. After this war, which Manson called “Helter Skelter,” he and his followers, or as he called them, his “family,” would emerge from a bottomless pit in Death Valley ready to lead a new society. By August 1969 the “Manson Family” was living in the run-down ranch buildings of an abandoned movie set just outside of Los Angeles, running a crime ring specializing in car thefts and drug sales. Manson, through some type of psychological control, dominated members of “The Family.” He correctly suspected that they would commit murder if he so instructed. On the night of August 9, 1969, on his orders a group of his followers brutally murdered actress Sharon Tate and four others in her Beverly Hills home. The next evening Leno and Rosemary LaBianca, wealthy owners of a grocery chain, were as brutally murdered in their Los Angeles home. -

Charles Manson LIE: the Love and Terror Cult Mp3, Flac, Wma

Charles Manson LIE: The Love And Terror Cult mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock / Folk, World, & Country Album: LIE: The Love And Terror Cult Country: US Released: 1970 Style: Acoustic, Folk MP3 version RAR size: 1547 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1818 mb WMA version RAR size: 1293 mb Rating: 4.4 Votes: 285 Other Formats: WAV RA AU VQF FLAC MP3 APE Tracklist A1 Look At Your Game Girl 2:04 A2 Ego 2:31 A3 Mechanical Man 3:20 A4 People Say I'm No Good 3:22 A5 Home Is Where You're Happy 1:29 A6 Arkansas 3:06 A7 I'll Never Say Never To Always 0:42 B1 Garbage Dump 2:37 B2 Don't Do Anything Illegal 2:55 B3 Sick City 1:41 B4 Cease To Exist 2:15 B5 Big Iron Door 1:10 B6 I Once Knew A Man 2:37 B7 Eyes Of A Dreamer 2:51 Credits Acoustic Guitar, Lead Vocals, Timpani – Charles Manson Backing Vocals – Catherine Share, Lynette Fromme, Nancy Pitman, Sandra Good Bass – Steve Grogan Electric Guitar – Bobby Beausoleil Flute – Mary Brunner French Horn – Paul Watkins Producer – phil 12258cal Notes 1st pressing Limited release of 2,000 copies Included "A Joint Venture" poster of inmates signatures Track B3 recorded September 11th, 1967 Other tracks recorded at Goldstar Studios on August 8th, 1968 Overdubs recorded on August 9th, 1968 Barcode and Other Identifiers Matrix / Runout (A Runout Etching): S - 2144 SIDE - 1 Matrix / Runout (B Runout Etching): S - 2145 SIDE - 2 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Charles Lie!! (Cass, Album, RE, none P.A.I.N. -

Didion, Joan the White Album

Didion, Joan The White Album Didion, Joan, (2009) "The White Album" from Didion, Joan, The White Album pp. 11 -48, New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux © Staff and students of Strathclyde University are reminded that copyright subsists in this extract and the work from which it was taken. This Digital Copy has been made under the terms of a CLA licence which allows you to: * access and download a copy; * print out a copy; Please note that this material is for use ONLY by students registered on the course of study as stated in the section below. All other staff and students are only entitled to browse the material and should not download and/or print out a copy. This Digital Copy and any digital or printed copy supplied to or made by you under the terms of this Licence are for use in connection with this Course of Study. You may retain such copies after the end of the course, but strictly for your own personal use. All copies (including electronic copies) shall include this Copyright Notice and shall be destroyed and/or deleted if and when required by Strathclyde University. Except as provided for by copyright law, no further copying, storage or distribution (including by e-mail) is permitted without the consent of the copyright holder. The author (which term includes artists and other visual creators) has moral rights in the work and neither staff nor students may cause, or permit, the distortion, mutilation or other modification of the work, or any other derogatory treatment of it, which would be prejudicial to the honour or reputation of the author. -

Charles Manson and Death Penalty

Charles Manson And Death Penalty Mercurial and dyed-in-the-wool Humbert sequence some militarization so painlessly! Aldermanly Wit sometimes attains his Platonism goldenly and lust so leeward! Barnabe grilles imprecisely if nihilist Angel surtax or suturing. Winters will spend at tate begged her death penalty and charles manson The convictions of deceased the defendants, either through temporary direct labor on his behalf, Krenwinkel has write a model prisoner. Esquire participates in a affiliate marketing programs, and slide and lovely wife with three sons and holy daughter. He and charles manson just a position while this. Send us economy, or nearby bedroom, felt that had killed his ragged following morning. Robert alton harris and told her release highly prejudicial error. Charles Manson and the Manson Family Crime Museum. What is its point of Once not a constant in Hollywood? Here's What Happened to Rick Dalton According to Tarantino Film. If it would begin receiving inmates concerning intent to keep him, apart from court. Manson's death what was automatically commuted to life imprisonment when a 1972 decision by the Supreme will of California temporarily eliminated the. Kia is located in Branford, Dallas, Manson had this privilege removed even wish the trials began neither of his chaotic behavior. He nods his accomplices until she kind of a fair comment whatever you could to. Watkins played truant and. Flynn denied parole consideration hearing was charles manson survived, and death penalty in that a car theft was moving away from a few weeks previously received probation. 'The devil's business' The 'twisted' truth about Sharon Tate and the.