Origins of the Witch Hunts Michael D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Universidade Federal De Minas Gerais Alexandra Lauren Corrêa

1 Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais Alexandra Lauren Corrêa Gabbard The Demonization of the Jew in Chaucer's “The Prioress's Tale,” Shakespeare's The Merchant of Venice and Scott's Ivanhoe Belo Horizonte 2011 2 Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais Alexandra Lauren Corrêa Gabbard The Demonization of the Jew in Chaucer's “The Prioress's Tale,” Shakespeare's The Merchant of Venice and Scott's Ivanhoe Dissertação de Mestrado apresentada à Faculdade de Letras da Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, como requisito para a obtenção do título de Mestre em Letras: Estudos Literários. Orientador: Thomas LaBorie Burns Belo Horizonte 2011 3 ABSTRACT This thesis examines the issue of anti-Semitism throughout three different eras in chosen classics of the English literature- “The Prioress’s Tale” from the Canterbury Tales, The Merchant of Venice and Ivanhoe- comparing and contrasting the demonization of the Jewish characters present in the texts. By examining the three texts, I intend to show the evolution of the demonization of Jews in literature throughout different periods in history. The historical and cultural aspects of the works will be taken into consideration, for anti- Semitism can be clearly traced as an ideology built throughout Western culture as a form of domination and exclusion of minorities. The Lateran Council of 1215 resurrected the spectrum of anti-Semitism by imposing laws such as the prohibition of intermarriage between Jews and Christians or the obligation of different dress for Jews. This is especially visible in the chosen works, for Jews are stigmatized as demonic, pagan, heretic and unclean. A particular trope present in two of the texts in the Christian aversion to usury- a task that was conveniently attributed to the Jews. -

The Pulpits and the Damned

THE PULPITS AND THE DAMNED WITCHCRAFT IN GERMAN POSTILS, 1520-1615 _______________________________________ A Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia _______________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts _____________________________________________________ by TANNER H. DEEDS Dr. John M. Frymire, Thesis Advisor DECEMBER 2018 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the thesis entitled THE PULPITS AND THE DAMNED: WITCHCRAFT IN GERMAN POSTILS, 1520- 1615 presented by Tanner H. Deeds a candidate for the degree of Master of Arts, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Professor John M. Frymire Professor Kristy Wilson-Bowers Professor Rabia Gregory I owe an enormous debt to my entire family; but my greatest debt is to my maternal grandmother Jacqueline Williams. Her love and teachings were instrumental in making me who I am today. Unfortunately, she passed away during the early stages of this project and is unable to share in the joys of its completion. My only hope is that whatever I become and whatever I accomplish is worthy of the time, treasure, and kindness she gave me. It is with the utmost joy and the most painful sorrow that I dedicate this work to her. ACKNOWLEGEMENTS At both the institutional and individual level, I have incurred more debts than I can ever hope to repay. Above all I must thank my advisor Dr. John Frymire. Dr. Frymire has been an exemplar advisor from my first day at the University of Missouri. Both in and out of the classroom, he has taught me more than I could have ever hoped when I began this journey. -

Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds an End to Antisemitism!

Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds An End to Antisemitism! Edited by Armin Lange, Kerstin Mayerhofer, Dina Porat, and Lawrence H. Schiffman Volume 5 Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds Edited by Armin Lange, Kerstin Mayerhofer, Dina Porat, and Lawrence H. Schiffman ISBN 978-3-11-058243-7 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-067196-4 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-067203-9 DOI https://10.1515/9783110671964 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. For details go to https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Library of Congress Control Number: 2021931477 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2021 Armin Lange, Kerstin Mayerhofer, Dina Porat, Lawrence H. Schiffman, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published with open access at www.degruyter.com Cover image: Illustration by Tayler Culligan (https://dribbble.com/taylerculligan). With friendly permission of Chicago Booth Review. Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck www.degruyter.com TableofContents Preface and Acknowledgements IX LisaJacobs, Armin Lange, and Kerstin Mayerhofer Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds: Introduction 1 Confronting Antisemitism through Critical Reflection/Approaches -

“The Devil Made Me Do It” the Deification of Consciousness and the Demonization of the Unconscious

CHAPTER 5 “The Devil Made Me Do It” The Deification of Consciousness and the Demonization of the Unconscious John A. Bargh Other chapters in this book on the social psychology of good and evil address important questions such as: What are the psychologi- cal processes that lead to positive, selfless, prosocial, and constructive behavior on the one hand or to negative, selfish, antisocial, and destruc- tive behavior on the other? Such questions concern how the state of a per- son’s mind and his or her current context or situation influences his or her actions upon the outside world. In this chapter, however, the causal direc- tion is reversed. The focus is instead on how the outside world of human beings—with its religious, medical, cultural, philosophical, and scientific traditions, its millennia-old ideologies and historical forces—has placed a value on types of psychological processes. It is on how these historical forces, even today, slant the field of psychological science, through basi- cally a background frame or mind set of implicit assumptions, to consider types of psychological processes themselves as being either good or evil (or at least problematic and producing negative outcomes). There exists a long historical tendency to consider one type of mental process to be the “good” one—our conscious and intentional, deliberate thought and behavior processes—and another type as the “bad” and even “evil” one—our automatic, impulsive, unintentional, and unconscious 69 Miller_Book.indb 69 12/8/2015 9:46:24 AM 70 CONCEPTUAL PERSPECTIVES ON GOOD AND EVIL FIGURE 5.1. Satan tempting John Wilkes Booth to the murder of President Abra- ham Lincoln (1865 lithograph by John L. -

On the Months (De Mensibus) (Lewiston, 2013)

John Lydus On the Months (De mensibus) Translated with introduction and annotations by Mischa Hooker 2nd edition (2017) ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Abbreviations .......................................................................................... iv Introduction .............................................................................................. v On the Months: Book 1 ............................................................................... 1 On the Months: Book 2 ............................................................................ 17 On the Months: Book 3 ............................................................................ 33 On the Months: Book 4 January ......................................................................................... 55 February ....................................................................................... 76 March ............................................................................................. 85 April ............................................................................................ 109 May ............................................................................................. 123 June ............................................................................................ 134 July ............................................................................................. 140 August ........................................................................................ 147 September ................................................................................ -

Origins of Valentine's Day

Origins of Valentine's Day Various Authors CHURCH OF GOD ARCHIVES Origins of Valentine's Day Valentine's Day - Christian Custom or Pagan Pageantry? by Herman L Hoeh "Will you be my valentine?" That question is asked by millions about this time of year. Why? Is there any religious significance to February 14? Where did St. Valentine's Day come from? You might suppose schoolteachers and educators would know. But do they? How many of you were ever taught the real origin of Valentine's Day — were ever told in school exactly why you should observe the custom of exchanging valentines? Teachers are all too often silent about the origin of the customs they are forced to teach in today's schools. If they were to speak out, many would lose their jobs! Today, candy makers unload tons of heart-shaped red boxes for February 14 — St. Valentine's Day — while millions of the younger set exchange valentines. Florists consider February 14 as one of their best business days. And young lovers pair off – at least for a dance or two — at St. Valentine's balls. Why? Where did these customs originate? How did we come to inherit these customs? Isn't it time we examined why we encourage our children to celebrate St. Valentine's Day? A Christian custom? Many have assumed that the traditional Valentine's Day celebrations are all in connection with an early Christian martyr by the name of Valentine. Nothing could be further from the truth! Notice what one encyclopedia says about this idea: "St. -

Pope Innocent VIII (1484-1492) and the Summis Desiderantes Affectibus

Portland State University PDXScholar Malleus Maleficarum and asciculusF Malleus Maleficarum Temporum (1490) 2020 Pope Innocent VIII (1484-1492) and the Summis desiderantes affectibus Maral Deyrmenjian Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/mmft_malleus Part of the European History Commons, History of Christianity Commons, Medieval History Commons, and the Medieval Studies Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Deyrmenjian, Maral, "Pope Innocent VIII (1484-1492) and the Summis desiderantes affectibus" (2020). Malleus Maleficarum. 1. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/mmft_malleus/1 This Book is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Malleus Maleficarum by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Maral Deyrmenjian Spring, 2020 Pope Innocent VIII (1484-1492) and the Summis desiderantes affectibus At the end of the fifteenth century, Dominican friars were authorized to persecute practitioners of certain local customs which were perceived to be witchcraft in the mountains of Northern Italy.1 A landmark in the chronology of these witch-hunts was the papal bull of 1484, or the Summis desiderantes affectibus, and its inclusion in Heinrich Kramer’s witch-hunting codex, the Malleus Maleficarum. While neither the pope nor the papal bull were significantly influential on their own, the extraordinary popularity of Kramer’s Malleus draws attention to them. Pope Innocent VIII, born Giovanni Battista Cibó, was born in Genoa in 1432 into a Roman senatorial family.2 Cibó did not intend to become a member of the clergy and, in fact, fathered two illegitimate children: Franceschetto and Teodorina. -

Witchcraft Historiography in the Twentieth Century Jon Burkhardt

15 16 Witchcraft Historiography in the Twentieth Century rural areas into the early modern period. Her ideas were completely rejected by other historians at the time, who viewed witchcraft rather as an example of early modern society’s superstitious nature and the intolerance of the Church. However, Carlo Ginzburg’s fascinating account of an isolated Italian peasant culture in Night Battles: Witchcraft and Agrarian Cults in the Jon Burkhardt Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries, and his recent re- construction of the witches’ Sabbath, conclusively demonstrate the Our evidence for witchcraft in Europe comes almost survival of ancient agrarian cults in some parts of Western exclusively from hostile sources—from trials and confessions of Europe.1 witches documented by educated “witnesses.” In addressing the In Night Battles, Ginzburg studied the peasants in early question of witchcraft in the Western tradition, historians have modern Friuli, a mountainous region in northeast Italy, and often disagreed as to its origins and essence. At least two major uncovered a bizarre set of ancient beliefs. The peasants believed interpretations—along with several minor interpretations—of that those individuals born with a caul possessed strange powers.2 European witchcraft are present in witchcraft historiography. The These people were called benandanti, or “good walkers.” “On first interpretation is known as the Murray-Ginzburg, or folklorist certain nights of the year” the benandanti “fell into a trance or interpretation. This view sees European witchcraft as the survival deep sleep…while their souls (sometimes in the form of small of an ancient fertility religion. The second interpretation, animals) left their bodies so that they could do battle, armed with currently the most influential, emphasizes the social and cultural stalks of fennel, against analogous companies of male witches,” history of witchcraft, especially the pattern of accusations. -

Cunning Folk and Wizards in Early Modern England

Cunning Folk and Wizards In Early Modern England University ID Number: 0614383 Submitted in part fulfilment for the degree of MA in Religious and Social History, 1500-1700 at the University of Warwick September 2010 This dissertation may be photocopied Contents Acknowledgements ii Abstract iii Introduction 1 1 Who Were White Witches and Wizards? 8 Origins 10 OccupationandSocialStatus 15 Gender 20 2 The Techniques and Tools of Cunning Folk 24 General Tools 25 Theft/Stolen goods 26 Love Magic 29 Healing 32 Potions and Protection from Black Witchcraft 40 3 Higher Magic 46 4 The Persecution White Witches Faced 67 Law 69 Contemporary Comment 74 Conclusion 87 Appendices 1. ‘Against VVilliam Li-Lie (alias) Lillie’ 91 2. ‘Popular Errours or the Errours of the people in matter of Physick’ 92 Bibliography 93 i Acknowledgements I would like to thank my undergraduate and postgraduate tutors at Warwick, whose teaching and guidance over the years has helped shape this dissertation. In particular, a great deal of gratitude goes to Bernard Capp, whose supervision and assistance has been invaluable. Also, to JH, GH, CS and EC your help and support has been beyond measure, thank you. ii Cunning folk and Wizards in Early Modern England Witchcraft has been a reoccurring preoccupation for societies throughout history, and as a result has inspired significant academic interest. The witchcraft persecutions of the early modern period in particular have received a considerable amount of historical investigation. However, the vast majority of this scholarship has been focused primarily on the accusations against black witches and the punishments they suffered. -

Copyright by Collin Laine Brown 2018

Copyright by Collin Laine Brown 2018 The Dissertation Committee for Collin Laine Brown Certifies that this is the approved version of the following Dissertation: CONVERSION, HERESY, AND WITCHCRAFT: THEOLOGICAL NARRATIVES IN SCANDINAVIAN MISSIONARY WRITINGS Committee: Marc Pierce, Supervisor Peter Hess Martha Newman Troy Storfjell Sandra Straubhaar CONVERSION, HERESY, AND WITCHCRAFT: THEOLOGICAL NARRATIVES IN SCANDINAVIAN MISSIONARY WRITINGS by Collin Laine Brown Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December 2018 Dedication Soli Deo gloria. Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to acknowledge my wife Robin. She especially helped me through the research and writing process, and kept me sane through the stress of having to spend so much time away from her while in graduate school. I wish that my late father Doug could be here, and I know that he would be thrilled to see me receive my PhD. It was his love of history that helped set me on the path I find myself today. My academic family has also been amazing during my time in graduate school. Good friends were always there to keep me motivated and stimulate my research. The professors involved in my project are also much deserving of my thanks: Marc Pierce, my advisor, as well as Sandra Straubhaar, Peter Hess, Martha Newman, and Troy Storfjell. I am grateful for their help and support, and for the opportunity to embark on this very interdisciplinary and very fulfilling project. -

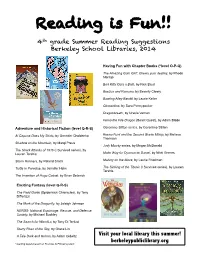

Reading List 4Th 2014.Pptx

Reading is Fun!! 4th grade Summer Reading Suggestions Berkeley School Libraries, 2014 Having Fun with Chapter Books (*level O-P-Q) The Amazing Gum Girl!: Chews your destiny, by Rhode Montijo Bad Kitty Gets a Bath, by Nick Bruel Beezus and Ramona, by Beverly Cleary Bowling Alley Bandit, by Laurie Keller Clementine, by Sara Pennypacker Dragonbreath, by Ursula Vernon Ferno the Fire Dragon (Beast Quest), by Adam Blade Adventure and Historical Fiction (level Q-R-S) Geronimo Stilton series, by Geronimo Stilton Al Capone Does My Shirts, by Gennifer Choldenko Keena Ford and the Second Grade Mixup, by Melissa Thomson Shadow on the Mountain, by Margi Preus Judy Moody series, by Megan McDonald The Shark Attacks of 1916 (I Survived series), by Lauren Tarshis Make Way for Dyamonde Daniel, by Nikki Grimes Storm Runners, by Roland Smith Mallory on the Move, by Laurie Friedman Turtle in Paradise, by Jennifer Holm The Sinking of the Titanic (I Survived series), by Lauren Tarshis The Invention of Hugo Cabret, by Brian Selznick Exciting Fantasy (level Q-R-S) The Field Guide (Spiderwick Chronicles), by Tony DiTerlizzi The Mark of the Dragonfly, by Jaleigh Johnson NERDS: National Espionage, Rescue, and Defense Society, by Michael Buckley The Search for WondLa, by Tony Di Terlizzi Starry River of the Sky, by Grace Lin A Tale Dark and Grimm, by Adam Gidwitz Visit your local library this summer! berkeleypubliclibrary.org * reading levels based on Fountas & Pinnell system Funny Stories (level R-S-T) The 13-Story Treehouse, by Andy Griffiths Dead End in Norvelt, by Jack Gantos Charlie Joe Jackson’s Guide to Summer Vacation, by Tommy Greenwald Flora and Ulysses, by Kate DiCamillo The Strange Case of Origami Yoda, by Tom Angleberger Stories that Touch Your Heart (level R-S-T) The Templeton Twins Have an Idea, by Ellis Weiner Counting By 7s, by Holly Goldberg Sloan Timmy Failure: Mistakes Were Made, by Stephan Pastis Dancing Home, by Alma Flor Ada Drita, My Homegirl, by Jenny Lombard Duke, by Kirby Larson Hold Fast, by Blue Balliett P.S. -

(Paper) -- Hunting Power Through Witch Hunts in Early Modern Scotland

Portland State University PDXScholar Young Historians Conference Young Historians Conference 2021 May 19th, 2:45 PM - 4:00 PM Session 2: Panel 1: Presenter 3 (Paper) -- Hunting Power through Witch Hunts in Early Modern Scotland Devika D. Narendra Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians Part of the History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Narendra, Devika D., "Session 2: Panel 1: Presenter 3 (Paper) -- Hunting Power through Witch Hunts in Early Modern Scotland" (2021). Young Historians Conference. 16. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians/2021/papers/16 This Event is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Young Historians Conference by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Narendra 2 “Be ane great storme: it wes feared that the Queine wes in danger upone the seas,”1 read King James VI of Scotland in a letter from Lord Dingwal. 2 The festivities celebrating his recent marriage would have to wait, King James VI needed to ensure his new wife, Queen Anne, would arrive safely in Scotland. King James VI stayed at the Seton House, watching the sea every day for approximately seventeen days, but the Queen did not come. 3 The king would have to retrieve her himself. The sea threw the king’s boat back and forth and rendered him fully powerless against the waves. The King and Queen were lucky to have survived their journey, one of Queen Anne’s gentlewomen, Jean Kennedy, having drowned in the same storm.4 Upon returning to Scotland, King James VI immediately ordered all of the accused witches of the North Berwick witch hunt to be brought to him, believing that the witches caused the dangerous sailing conditions, intending to kill him.5 To protect himself, he tortured and executed witches, prosecuting them for both witchcraft and conspiring against the King.