H-Diplo Article Review No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

H-Diplo Article Roundtable Review, Vol. X, No. 24

2009 h-diplo H-Diplo Article Roundtable Roundtable Editors: Thomas Maddux and Diane Labrosse Roundtable Web Editor: George Fujii Review Introduction by Thomas Maddux www.h-net.org/~diplo/roundtables Reviewers: Bruce Craig, Ronald Radosh, Katherine A.S. Volume X, No. 24 (2009) Sibley, G. Edward White 17 July 2009 Response by John Earl Haynes and Harvey Klehr Journal of Cold War Studies 11.3 (Summer 2009) Special Issue: Soviet Espoinage in the United States during the Stalin Era (with articles by John Earl Haynes and Harvey Klehr; Eduard Mark; Gregg Herken; Steven T. Usdin; Max Holland; and John F. Fox, Jr.) http://www.mitpressjournals.org/toc/jcws/11/3 Stable URL: http://www.h-net.org/~diplo/roundtables/PDF/Roundtable-X-24.pdf Contents Introduction by Thomas Maddux, California State University, Northridge.............................. 2 Review by Bruce Craig, University of Prince Edward Island ..................................................... 8 Review by Ronald Radosh, Emeritus, City University of New York ........................................ 16 Review by Katherine A.S. Sibley, St. Josephs University ......................................................... 18 Review by G. Edward White, University of Virginia School of Law ........................................ 23 Author’s Response by John Earl Haynes, Library of Congress, and Harvey Klehr, Emory University ................................................................................................................................ 27 Copyright © 2009 H-Net: Humanities and Social Sciences Online. H-Net permits the redistribution and reprinting of this work for non-profit, educational purposes, with full and accurate attribution to the author(s), web location, date of publication, H-Diplo, and H-Net: Humanities & Social Sciences Online. For other uses, contact the H-Diplo editorial staff at [email protected]. H-Diplo Roundtable Reviews, Vol. -

The Copyright of This Recording Is Vested in the BECTU History Project

Elizabeth Furse Tape 1 Side A This recording was transcribed by funds from the AHRC-funded ‘History of Women in British Film and Television project, 1933-1989’, led by Dr Melanie Bell (Principal Investigator, University of Leeds) and Dr Vicky Ball (Co-Investigator, De Montfort University). (2015). COPYRIGHT: No use may be made of any interview material without the permission of the BECTU History Project (http://www.historyproject.org.uk/). Copyright of interview material is vested in the BECTU History Project (formerly the ACTT History Project) and the right to publish some excerpts may not be allowed. CITATION: Women’s Work in British Film and Television, Elizabeth Furse, http://bufvc.ac.uk/bectu/oral-histories/bectu-oh [date accessed] By accessing this transcript, I confirm that I am a student or staff member at a UK Higher Education Institution or member of the BUFVC and agree that this material will be used solely for educational, research, scholarly and non-commercial purposes only. I understand that the transcript may be reproduced in part for these purposes under the Fair Dealing provisions of the 1988 Copyright, Designs and Patents Act. For the purposes of the Act, the use is subject to the following: The work must be used solely to illustrate a point The use must not be for commercial purposes The use must be fair dealing (meaning that only a limited part of work that is necessary for the research project can be used) The use must be accompanied by a sufficient acknowledgement. Guidelines for citation and proper acknowledgement must be followed (see above). -

House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC)

Cold War PS MB 10/27/03 8:28 PM Page 146 House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) Excerpt from “One Hundred Things You Should Know About Communism in the U.S.A.” Reprinted from Thirty Years of Treason: Excerpts From Hearings Before the House Committee on Un-American Activities, 1938–1968, published in 1971 “[Question:] Why ne Hundred Things You Should Know About Commu- shouldn’t I turn “O nism in the U.S.A.” was the first in a series of pam- Communist? [Answer:] phlets put out by the House Un-American Activities Commit- You know what the United tee (HUAC) to educate the American public about communism in the United States. In May 1938, U.S. represen- States is like today. If you tative Martin Dies (1900–1972) of Texas managed to get his fa- want it exactly the vorite House committee, HUAC, funded. It had been inactive opposite, you should turn since 1930. The HUAC was charged with investigation of sub- Communist. But before versive activities that posed a threat to the U.S. government. you do, remember you will lose your independence, With the HUAC revived, Dies claimed to have gath- ered knowledge that communists were in labor unions, gov- your property, and your ernment agencies, and African American groups. Without freedom of mind. You will ever knowing why they were charged, many individuals lost gain only a risky their jobs. In 1940, Congress passed the Alien Registration membership in a Act, known as the Smith Act. The act made it illegal for an conspiracy which is individual to be a member of any organization that support- ruthless, godless, and ed a violent overthrow of the U.S. -

Report on Civil Rights Congress As a Communist Front Organization

X Union Calendar No. 575 80th Congress, 1st Session House Report No. 1115 REPORT ON CIVIL RIGHTS CONGRESS AS A COMMUNIST FRONT ORGANIZATION INVESTIGATION OF UN-AMERICAN ACTIVITIES IN THE UNITED STATES COMMITTEE ON UN-AMERICAN ACTIVITIES HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ^ EIGHTIETH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION Public Law 601 (Section 121, Subsection Q (2)) Printed for the use of the Committee on Un-American Activities SEPTEMBER 2, 1947 'VU November 17, 1947.— Committed to the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1947 ^4-,JH COMMITTEE ON UN-AMERICAN ACTIVITIES J. PARNELL THOMAS, New Jersey, Chairman KARL E. MUNDT, South Dakota JOHN S. WOOD, Georgia JOHN Mcdowell, Pennsylvania JOHN E. RANKIN, Mississippi RICHARD M. NIXON, California J. HARDIN PETERSON, Florida RICHARD B. VAIL, Illinois HERBERT C. BONNER, North Carolina Robert E. Stripling, Chief Inrestigator Benjamin MAi^Dt^L. Director of Research Union Calendar No. 575 SOth Conokess ) HOUSE OF KEriiEfcJENTATIVES j Report 1st Session f I1 No. 1115 REPORT ON CIVIL RIGHTS CONGRESS AS A COMMUNIST FRONT ORGANIZATION November 17, 1917. —Committed to the Committee on the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed Mr. Thomas of New Jersey, from the Committee on Un-American Activities, submitted the following REPORT REPORT ON CIVIL RIGHTS CONGRESS CIVIL RIGHTS CONGRESS 205 EAST FORTY-SECOND STREET, NEW YORK 17, N. T. Murray Hill 4-6640 February 15. 1947 HoNOR.\RY Co-chairmen Dr. Benjamin E. Mays Dr. Harry F. Ward Chairman of the board: Executive director: George Marshall Milton Kaufman Trea-surcr: Field director: Raymond C. -

Next Witness. Mr. STRIPLING. Mr. Berthold Brecht. the CHAIRMAN

Next witness. committee whether or not you are a citizen of the United States? Mr. STRIPLING. Mr. Berthold Brecht. Mr. BRECHT. I am not a citizen of the United States; I have The CHAIRMAN. Mr. Becht, will you stand, please, and raise only my first papers. your right hand? Mr. STRIPLING. When did you acquire your first papers? Do you solemnly swear the testimony your are about to give is the Mr. BRECHT. In 1941 when I came to the country. truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth, so help you God? Mr. STRIPLING. When did you arrive in the United States? Mr. BRECHT. I do. Mr. BRECHT. May I find out exactly? I arrived July 21 at San The CHAIRMAN. Sit down, please. Pedro. Mr. STRIPLING. July 21, 1941? TESTIMONY OF BERTHOLD BRECHT (ACCOMPANIED BY Mr. BRECHT. That is right. COUNSEL, MR. KENNY AND MR. CRUM) Mr. STRIPLING. At San Pedro, Calif.? Mr. Brecht. Yes. Mr. STRIPLING. Mr. Brecht, will you please state your full Mr. STRIPLING. You were born in Augsburg, Bavaria, Germany, name and present address for the record, please? Speak into the on February 10, 1888; is that correct? microphone. Mr. BRECHT. Yes. Mr. BRECHT. My name is Berthold Brecht. I am living at 34 Mr. STRIPLING. I am reading from the immigration records — West Seventy-third Street, New York. I was born in Augsburg, Mr. CRUM. I think, Mr. Stripling, it was 1898. Germany, February 10, 1898. Mr. BRECHT. 1898. Mr. STRIPLING. Mr. Brecht, the committee has a — Mr. STRIPLING. I beg your pardon. -

Inventory for Congressional Period Collection

Congressional Period. Work File. – House Committee on Un-American Activities. (PPS 205) (Materials in bold type is available for research) [Boxes 1-10 covered under Congressional Collection Finding Aid] Box 11 : Hiss case: Grand Jury testimony – Index. Hiss case: Grand Jury testimony – 1947, July 22 – Abraham Brothman. Hiss case: Grand Jury testimony – 1947, July 31 – FBI agent. Hiss case: Grand Jury testimony – 1947, July 31 – Harry Gold. Hiss case: Grand Jury testimony – 1947, Nov. 24 – Louis Budenz. Hiss case: Grand Jury testimony – 1947, Nov. 25 – FBI agent. Hiss case: Grand Jury testimony – 1947, Nov. 25 – Julius J. Joseph. Hiss case: Grand Jury testimony – 1947, Dec. 2 – Norman Bursler. Hiss case: Grand Jury testimony – 1947, Dec. 3 – FBI agent. Hiss case: Grand Jury testimony – 1947, Dec. 3 – Mary Price. Hiss case: Grand Jury testimony – 1948, Jan. 20 – FBI agent. Hiss case: Grand Jury testimony – 1948, Jan. 20 – Solomon Adler. Hiss case: Grand Jury testimony – 1948, Feb. 10 – FBI agent. Hiss case: Grand Jury testimony – 1948, Feb. 10 – FBI agent. Hiss case: Grand Jury testimony – 1948, Mar. 16. – FBI agent. Hiss case: Grand Jury testimony – 1948, Mar. 16 – Alger Hiss. Hiss case: Grand Jury testimony – 1948, Mar. 23 – FBI agent. Hiss case: Grand Jury testimony – 1948, Mar. 24-25 – Harry Dexter White. Hiss case: Grand Jury testimony – 1948, Mar. 30 – Elizabeth Bentley. Hiss case: Grand Jury testimony – 1948, Mar. 31-Apr. 1 – Lement Harris. Hiss case: Grand Jury testimony – 1948, Apr. 6 – Elizabeth Bentley. Hiss case: Grand Jury testimony – 1948, Apr. 7 – Maurice Joseph Berg. Hiss case: Grand Jury testimony – 1948, Apr. -

Dialectic of Solidarity Studies in Critical Social Sciences

Dialectic of Solidarity Studies in Critical Social Sciences Series Editor DAVID FASENFEST Wayne State University Editorial Board JOAN ACKER, Department of Sociology, University of Oregon ROSE BREWER, Afro-American and African Studies, University of Minnesota VAL BURRIS, Department of Sociology, University of Oregon CHRIS CHASE-DUNN, Department of Sociology, University of California-Riverside G. WILLIAM DOMHOFF, Department of Sociology, University of California-Santa Cruz COLETTE FAGAN, Department of Sociology, Manchester University MATHA GIMENEZ, Department of Sociology, University of Colorado, Boulder HEIDI GOTTFRIED, Department of Sociology, Wayne State University KARIN GOTTSCHALL, Zentrum für Sozialpolitik, University of Bremen BOB JESSOP, Department of Sociology, Lancaster University RHONDA LEVINE, Department of Sociology, Colgate University JACQUELINE O’REILLY, Department of Sociology, University of Sussex MARY ROMERO, School of Justice Studies, Arizona State University CHIZUKO URNO, Department of Sociology, University of Tokyo VOLUME 11 Dialectic of Solidarity Labor, Antisemitism, and the Frankfurt School By Mark P. Worrell LEIDEN • BOSTON 2008 Cover design: Wim Goedhart This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Worrell, Mark. Dialectic of solidarity : labor, antisemitism, and the Frankfurt School / by Mark Worrell. p. cm. — (Studies in critical social sciences) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-16886-2 (hbk. : alk. paper) 1. Working class—United States— Attitudes. 2. Antisemitism—United States. 3. Frankfurt school of sociology. I. Title. II. Series. HD8072.W83 2008 301.01—dc22 2008011351 ISSN: 1573-4234 ISBN: 978 90 04 16886 2 Copyright 2008 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers and VSP. -

ABSTRACT Title of Document: from the BELLY of the HUAC: the RED PROBES of HOLLYWOOD, 1947-1952 Jack D. Meeks, Doctor of Philos

ABSTRACT Title of Document: FROM THE BELLY OF THE HUAC: THE RED PROBES OF HOLLYWOOD, 1947-1952 Jack D. Meeks, Doctor of Philosophy, 2009 Directed By: Dr. Maurine Beasley, Journalism The House Un-American Activities Committee, popularly known as the HUAC, conducted two investigations of the movie industry, in 1947 and again in 1951-1952. The goal was to determine the extent of communist infiltration in Hollywood and whether communist propaganda had made it into American movies. The spotlight that the HUAC shone on Tinsel Town led to the blacklisting of approximately 300 Hollywood professionals. This, along with the HUAC’s insistence that witnesses testifying under oath identify others that they knew to be communists, contributed to the Committee’s notoriety. Until now, historians have concentrated on offering accounts of the HUAC’s practice of naming names, its scrutiny of movies for propaganda, and its intervention in Hollywood union disputes. The HUAC’s sealed files were first opened to scholars in 2001. This study is the first to draw extensively on these newly available documents in an effort to reevaluate the HUAC’s Hollywood probes. This study assesses four areas in which the new evidence indicates significant, fresh findings. First, a detailed analysis of the Committee’s investigatory methods reveals that most of the HUAC’s information came from a careful, on-going analysis of the communist press, rather than techniques such as surveillance, wiretaps and other cloak and dagger activities. Second, the evidence shows the crucial role played by two brothers, both German communists living as refugees in America during World War II, in motivating the Committee to launch its first Hollywood probe. -

The Cultural Cold War the CIA and the World of Arts and Letters

The Cultural Cold War The CIA and the World of Arts and Letters FRANCES STONOR SAUNDERS by Frances Stonor Saunders Originally published in the United Kingdom under the title Who Paid the Piper? by Granta Publications, 1999 Published in the United States by The New Press, New York, 2000 Distributed by W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., New York The New Press was established in 1990 as a not-for-profit alternative to the large, commercial publishing houses currently dominating the book publishing industry. The New Press oper- ates in the public interest rather than for private gain, and is committed to publishing, in in- novative ways, works of educational, cultural, and community value that are often deemed insufficiently profitable. The New Press, 450 West 41st Street, 6th floor. New York, NY 10036 www.thenewpres.com Printed in the United States of America ‘What fate or fortune led Thee down into this place, ere thy last day? Who is it that thy steps hath piloted?’ ‘Above there in the clear world on my way,’ I answered him, ‘lost in a vale of gloom, Before my age was full, I went astray.’ Dante’s Inferno, Canto XV I know that’s a secret, for it’s whispered everywhere. William Congreve, Love for Love Contents Acknowledgements .......................................................... v Introduction ....................................................................1 1 Exquisite Corpse ...........................................................5 2 Destiny’s Elect .............................................................20 3 Marxists at -

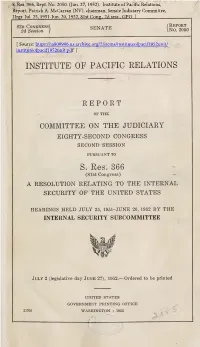

Institute of Pacific Relations. Report

f t I S. Res. 366, Rept. No. 2050. (Jun. 27, 1952). Institute of Pacific Relations, Report, Patrick A. McCarran (NV), chairman, Senate Judiciary Committee, Hrgs. Jul. 25, 1951-Jun. 20, 1952, 81st Cong., 2d sess., GPO. ] s^^^^™ ^^i.?.sri {sraSio [ Source: https://ia800906.us.archive.org/2/items/instituteofpacif1952unit/ instituteofpacif1952unit.pd"a f ] INSTITUTE OF PACIFIC RELATIONS REPORT OF THE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY EIGHTY-SECOND CONGRESS SECOND SESSION PURSUANT TO S. Res. 366 (81st Congress) — A RESOLUTION RELATING TO THE INTERNAL SECURITY OF THE UNITED STATES HEARINGS HELD JULY 25, 1951-JUNE 20, 1952 BY THE INTERNAL SECURITY SUBCOMMITTEE July 2 (legislative day June 27), 1952.—Ordered to be printed UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 21705 WASHINGTON : 1952 t? <?-'> -!*TTT .Kb M.!335.4AIS 4 Given By TT Q QTyPT nT7 HP t S^ " *''^-53r,4 I6f / U. S. SUPERINTENDENT OF DOCUMENT AUG 11 1952 COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY PAT McCARRAN, Nevada, Chairman HARLEY M. KILGORE, West Virginia ALEXANDER WILEY, Wisconsin JAMES O. EASTLAND, Mississippi WILLIAM LANGER, Nortli Dakota WARREN G. MAGNUSON, Washington HOMER FERGUSON, Michigan HERBERT R. O'CONOR, Maryland WILLIAM E. JENNER, Indiana ESTES KEFAUVER, Tennessee ARTHUR V. WATKINS, Utah WILLIS SMITH, North Carolina ROBERT C. HENDRICKSON, New Jersey J. G. SorRwiNE, Counsel Internal Security Subcommittee PAT McCARRAN, Nevada, Chairman JAMES O. EASTLAND, Mississippi HOMER FERGUSON, Michigan HERBERT R. O'CONOR, Maryland WILLIAM E. JENNER, Indiana WILLIS SMITH, North Carolina ARTHUR V. WATKINS, Utah Robert Morris, Special Counsel Benjamin' Mandel, Director of Research Subcommittee Investigating the Institute of Pacific Relations JAMES O. EASTLAND, Mississippi, Chairman PAT McCARRAN, Nevada HOMER FERGUSON, Michigan II CONTENTS Page Introduction 1 What is IPR? 3 Effect of the Inscitute of Pacific Relations on United States public opinion. -

Book Reviews

BOOK REVIEWS Kati Marton, True Believer: Stalin’s Last American Spy.NewYork:Simon&Schuster, 2016. 289 pp. $27.00. Reviewed by R. Bruce Craig, University of New Brunswick, Fredericton True Believer chronicles the life and times of Cold War–era espionage agent Noel Field and, to a lesser extent, the life of his wife, Herta, both of whom remained steadfast believers in the ideals and promises of Soviet-style Communism even when it had fallen out of fashion. In telling their story, Kati Marton paints a vivid and somewhat sympathetic portrait of the couple. She draws in a cast of characters, including Paul and Hede Massing, Alger Hiss, Lawrence Duggan, J. Peters (aka Sandor Goldberger), Allen Dulles, “Wild Bill” Donovan, and Iosif Stalin. A major strength of the book is Marton’s success in integrating these characters and their beliefs into the context of the times. The result is not only a balanced biography of Noel Field but also a nuanced account of espionage during the Red Decade and early Cold War era. Marton is uniquely qualified to tell this story. Like Field, her father was a political prisoner of the Hungarian Communists who for a time occupied the same cell with Field. Later, after both men were released from prison, Marton’s parents interviewed Noel and Herta, earning the distinction of being the only Western journalists ever to do so. Marton came to possess her parent’s notes of that interview, which, when combined with private correspondence from cooperating surviving members of the Field family, enabled her to flesh out the story of Noel Field, assessing his motives and adeptly placing him in his era. -

Reactions of Congress to the Alger Hiss Case, 1948-1960

Soviet Spies and the Fear of Communism in America Reactions of Congress to the Alger Hiss Case, 1948-1960 Mémoire Brigitte Rainville Maîtrise en histoire Maître ès arts (M.A.) Québec, Canada © Brigitte Rainville, 2013 Résumé Le but de ce mémoire est de mettre en évidence la réaction des membres du Congrès des États-Unis dans le cadre de l'affaire Alger Hiss de 1948 à 1960. Selon notre source principale, le Congressional Record, nous avons pu faire ressortir les divergences d'opinions qui existaient entre les partisans des partis démocrate et républicain. En ce qui concerne les démocrates du Nord, nous avons établi leur tendance à nier le fait de l'infiltration soviétique dans le département d'État américain. De leur côté, les républicains ont profité du cas de Hiss pour démontrer l'incompétence du président Truman dans la gestion des affaires d'État. Il est intéressant de noter que, à la suite de l'avènement du républicain Dwight D. Eisenhower à la présidence en 1953, un changement marqué d'opinions quant à l'affaire Hiss s'opère ainsi que l'attitude des deux partis envers le communisme. Les démocrates, en fait, se mettent à accuser l'administration en place d'inaptitude dans l'éradication des espions et des communistes. En ayant recours à une stratégie similaire à celle utilisée par les républicains à l'époque Truman, ceux-ci n'entachent toutefois guère la réputation d'Eisenhower. Nous terminons en montrant que le nom d'Alger Hiss, vers la fin de la présidence Eisenhower, s'avère le symbole de la corruption soviétique et de l'espionnage durant cette période marquante de la Guerre Froide.