Getting the Knack: 20 Poetry Writing Exercises 20

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wordback to CONTENTS P AGE 1 WHA T IS the WORD P an P AN

WHAT IS THE WORD WHAT PAN PAN PAN BACK TO CONTENTS PAGE 1 WHaT WOrD IS THE WHAT IS THE WORD WHAT PAN PAN PAN BACK TO CONTENTS PAGE 2 COnTEnTS WHAT IS THE WORD WHAT CONTENTS Contents Essay 4 Poems 8 Creatives 13 Creative Biographies 15 Speaker Biographies 20 CONTENTS BACK TO Pan Pan 32 PAGE 3 PAGE WHAT IS THE WORD WHAT Once more, with colour by Nicholas Johnson Speaking from experience, not everyone is overjoyed by an invitation to a poetry performance. It is not a clearly defined event with formal conditions: it could lead to a wide range of possible outcomes and feelings in the listener. The bardic tradition that sweeps across human cultures and histories — from the Homeric ESSAY epics to the Sufis, from the biwa hoshi of Japan to the filí of Ireland — shows both the depth and breadth of the human impulse to hear verse aloud. But in our cosmopolitan present, poetry being “voiced” could run the gamut from adolescent (painful sincerity at an open mic) to adult (earnest readings at university book launches) to transhuman (Black Thought’s ten-minute freestyle). Though poetry always transports us somewhere, the destination could be anywhere in Dante’s universe: infernal, purgatorial, or paradisiacal. This particular poetry performance is, perhaps fittingly for the year 2020, set in that everyday limbo that is the cinema. It is consciously conceived for the large-scale screen — a crucial gesture, when so much life is being lived on small screens — and as a physical, collective experience, with an audience in plush CONTENTS BACK TO seats, bathed in light, feeling the powerful surround-sound system within their bodies. -

Melissa Dejesus

Melissa DeJesus Mobile 646 344 2877 Website http://melissade.daportfolio.com/ Email [email protected] Passionate about motivating and inspiring children and teens in expression and critical thinking through the arts using the best in comics, animation, illustration, storytelling and design. Always looking to challenge myself, learn from others, and enjoy teaching others about self representation through art. My interests and skills extend over a vast array of genres and fields of professions. I'm looking to continue my career in education to offer the best of my experience and enthusiasm. Education The School of Visual Arts MAT Art Education 2013-2014 BFA Animation 1998-2002 Employment Harper Collins Publishing 2013-2014 Relevant Comic Illustrator Illustrated 7 page black and white comic excerpt for teen novel. Awesome Forces Productions Fall 2012 Assistant Animator Collaborated with partner in creating animation key frames for animated segments featured in TV series entitled The Aquabats! Super Show! Yen Press 2012-current Graphic Novel Illustrator Illustrated a full color chapters for a graphic novel entitled Monster Galaxy. Created and designed new characters along with existing characters in the online game franchise. Random House 2012-2013 Letterer / Retouch Artist Digitally retouched Japanese graphic novels for sub-division, Kodansha. Lettered 200+ comic pages and designed supplemental pages. Organized and prepared interior book files for print production. King Features Syndicate 2006-2010 Comic Strip Illustrator Digitally illustrated, colored and lettered daily comic strip, My Cage, for newspapers across the country from Hawaii to South Africa. Designed numerous characters on a day to day basis for growing cast. -

Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, a MATTER of LIFE and DEATH/ STAIRWAY to HEAVEN (1946, 104 Min)

December 8 (XXXI:15) Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, A MATTER OF LIFE AND DEATH/ STAIRWAY TO HEAVEN (1946, 104 min) (The version of this handout on the website has color images and hot urls.) Written, Produced and Directed by Michael Powell & Emeric Pressburger Music by Allan Gray Cinematography by Jack Cardiff Film Edited by Reginald Mills Camera Operator...Geoffrey Unsworth David Niven…Peter Carter Kim Hunter…June Robert Coote…Bob Kathleen Byron…An Angel Richard Attenborough…An English Pilot Bonar Colleano…An American Pilot Joan Maude…Chief Recorder Marius Goring…Conductor 71 Roger Livesey…Doctor Reeves Robert Atkins…The Vicar Bob Roberts…Dr. Gaertler Hour of Glory (1949), The Red Shoes (1948), Black Narcissus Edwin Max…Dr. Mc.Ewen (1947), A Matter of Life and Death (1946), 'I Know Where I'm Betty Potter…Mrs. Tucker Going!' (1945), A Canterbury Tale (1944), The Life and Death of Abraham Sofaer…The Judge Colonel Blimp (1943), One of Our Aircraft Is Missing (1942), 49th Raymond Massey…Abraham Farlan Parallel (1941), The Thief of Bagdad (1940), Blackout (1940), The Robert Arden…GI Playing Bottom Lion Has Wings (1939), The Edge of the World (1937), Someday Robert Beatty…US Crewman (1935), Something Always Happens (1934), C.O.D. (1932), Hotel Tommy Duggan…Patrick Aloyusius Mahoney Splendide (1932) and My Friend the King (1932). Erik…Spaniel John Longden…Narrator of introduction Emeric Pressburger (b. December 5, 1902 in Miskolc, Austria- Hungary [now Hungary] —d. February 5, 1988, age 85, in Michael Powell (b. September 30, 1905 in Kent, England—d. Saxstead, Suffolk, England) won the 1943 Oscar for Best Writing, February 19, 1990, age 84, in Gloucestershire, England) was Original Story for 49th Parallel (1941) and was nominated the nominated with Emeric Pressburger for an Oscar in 1943 for Best same year for the Best Screenplay for One of Our Aircraft Is Writing, Original Screenplay for One of Our Aircraft Is Missing Missing (1942) which he shared with Michael Powell and 49th (1942). -

Death and Dying in 20Th Century African American Literature Chayah Amayala Stoneberg-Cooper University of South Carolina - Columbia

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 1-1-2013 Going Hard, Going Easy, Going Home: Death and Dying in 20th Century African American Literature Chayah Amayala Stoneberg-Cooper University of South Carolina - Columbia Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Stoneberg-Cooper, C. A.(2013). Going Hard, Going Easy, Going Home: Death and Dying in 20th Century African American Literature. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/2440 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GOING HARD, GOING EASY, GOING HOME: DEATH AND DYING IN TWENTIETH-CENTURY AFRICAN AMERICAN LITERATURE by Chayah Stoneberg-Cooper Bachelor of Arts University of Oregon, 2001 Master of Arts University of California, San Diego, 2003 Master of Arts New York University, 2005 Master of Social Work University of South Carolina, 2011 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Literature College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2013 Accepted by: Qiana Whitted, Major Professor Kwame Dawes, Committee Member Folashade Alao, Committee Member Bobby Donaldson, Committee Member Lacy Ford, Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies © Copyright by Chayah Stoneberg-Cooper, 2013 All Rights Reserved. ii DEDICATION This work is dedicated to my family and friends, often one and the same, both living and dead, whose successes and struggles have made the completion of this work possible. -

The Evocation of the Physical, Metaphysical, and Sonic Landscapes in Samuel Beckett's Short Dramatic Works

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Senior Theses and Projects Student Scholarship Spring 2012 The Evocation of the Physical, Metaphysical, and Sonic Landscapes in Samuel Beckett's Short Dramatic Works Theresa A. Incampo Trinity College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses Part of the Dramatic Literature, Criticism and Theory Commons, Performance Studies Commons, and the Theatre History Commons Recommended Citation Incampo, Theresa A., "The Evocation of the Physical, Metaphysical, and Sonic Landscapes in Samuel Beckett's Short Dramatic Works". Senior Theses, Trinity College, Hartford, CT 2012. Trinity College Digital Repository, https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses/209 The Evocation of the Physical, Metaphysical and Sonic Landscapes within the Short Dramatic Works of Samuel Beckett Submitted by Theresa A. Incampo May 4, 2012 Trinity College Department of Theater and Dance Hartford, CT 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements 5 I: History Time, Space and Sound in Beckett’s short dramatic works 7 A historical analysis of the playwright’s theatrical spaces including the concept of temporality, which is central to the subsequent elements within the physical, metaphysical and sonic landscapes. These landscapes are constructed from physical space, object, light, and sound, so as to create a finite representation of an expansive, infinite world as it is perceived by Beckett’s characters.. II: Theory Phenomenology and the conscious experience of existence 59 The choice to focus on the philosophy of phenomenology centers on the notion that these short dramatic works present the theatrical landscape as the conscious character perceives it to be. The perceptual experience is explained by Maurice Merleau-Ponty as the relationship between the body and the world and the way as to which the self-limited interior space of the mind interacts with the limitless exterior space that surrounds it. -

CWC Newsletter Summer (July:Aug) 2020

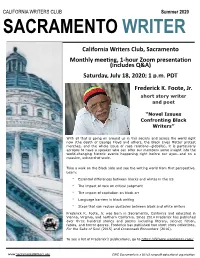

CALIFORNIA WRITERS CLUB Summer 2020 SACRAMENTO WRITER California Writers Club, Sacramento Monthly mee7ng, 1-hour Zoom presenta7on (includes Q&A) Saturday, July 18, 2020; 1 p.m. PDT Frederick K. Foote, Jr. short story writer and poet “Novel Issues Confronting Black Writers” With all that is going on around us in this society and across the world right now (the death of George Floyd and others, the Black Lives Matter protest marches, and the whole issue of race relations--globally), it is particularly apropos to have a speaker who can offer our members some insight into the world-changing historic events happening right before our eyes--and on a massive, unheard-of scale. Take a walk on the Black side and see the writing world from that perspective. Learn: • Essential differences between blacks and whites in the US • The impact of race on critical judgment • The impact of capitalism on black art • Language barriers in black writing • Steps that can reduce obstacles between black and white writers Frederick K. Foote, Jr. was born in Sacramento, California and educated in Vienna, Virginia, and northern California. Since 2014 Frederick has published over three hundred stories and poems including literary, science fiction, fables, and horror genres. Frederick has published two short story collections, For the Sake of Soul (2015) and Crossroads Encounters (2016). To see a list of Frederick’s publications, go to https://fkfoote.wordpress.com/ www.SacramentoWriters.org CWC Sacramento is a 501c3 nonprofit educational organization First Friday Networking Zoom July 3, 2020 at 10 a.m. Mini-Crowdsource Opportunity The CWC First Friday Zoom network meeting will be an opportunity to bring your most intractable, gruesome, horrendous, writing challenge to our forum of compassionate writers for solution. -

Waiting for Godot by Samuel Beckett

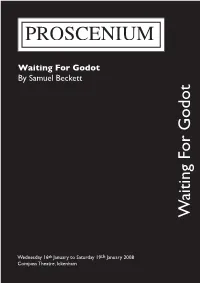

PROSCENIUM Waiting For Godot By Samuel Beckett Waiting For Godot For Waiting Wednesday 16th January to Saturday 19th January 2008 Compass Theatre, Ickenham PROSCENIUM Waiting For Godot By Samuel Beckett Waiting For Godot For Waiting Wednesday 16th January to Saturday 19th January 2008 Compass Theatre, Ickenham WAITING FOR GODOT The Author 1906 Born on Good Friday, April 13th, at Foxrock, near Dublin, son of a quantity surveyor. Both parents were Protestants. BY SAMUEL BECKETT 1920-3 Educated at Portora Royal School, Ulster. 1923-7 Trinity College, Dublin. In BA examinations placed first in first class in Modern Literature (French and Italian). Summer 1926: first contact with France, a bicycle tour of the chateaux of the Loire. 1927-8 Taught for two terms at Campbell College, Belfast. CAST: 1928-30 Exchange lecturer in Paris. Meets James Joyce. 1930 First separately published work, a poem Whoroscope. Four terms as assistant lecturer in French, Trinity College, Dublin. Estragon.....................................................................................................Duncan Sykes Helped translate Joyce’s Anna Livia Plurabella into French. 1931 Performance of first dramatic work, Le Kid, a parody sketch Vladimir ................................................................................................ Mark Sutherland after Corneille. Proust, his only major piece of literary criticism, Pozzo .............................................................................................................. Robert Ewen published. -

Songs in Fixed Forms

Songs in Fixed Forms by Margaret P. Hasselman 1 Introduction Fourteenth century France saw the development of several well-defined song structures. In contrast to the earlier troubadours and trouveres, the 14th-century songwriters established standardized patterns drawn from dance forms. These patterns then set up definite expectations in the listeners. The three forms which became standard, which are known today by the French term "formes fixes" (fixed forms), were the virelai, ballade and rondeau, although those terms were rarely used in that sense before the middle of the 14th century. (An older fixed form, the lai, was used in the Roman de Fauvel (c. 1316), and during the rest of the century primarily by Guillaume de Machaut.) All three forms make use of certain basic structural principles: repetition and contrast of music; correspondence of music with poetic form (syllable count and rhyme); couplets, in which two similar phrases or sections end differently, with the second ending more final or "closed" than the first; and refrains, where repetition of both words and music create an emphatic reference point. Contents • Definitions • Historical Context • Character and Provenance, with reference to specific examples • Notes and Selected Bibliography Definitions The three structures can be summarized using the conventional letters of the alphabet for repeated sections. Upper-case letters indicate that both text and music are identical. Lower-case letters indicate that a section of music is repeated with different words, which necessarily follow the same poetic form and rhyme-scheme. 1. Virelai The virelai consists of a refrain; a contrasting verse section, beginning with a couplet (two halves with open and closed endings), and continuing with a section which uses the music and the poetic form of the refrain; and finally a reiteration of the refrain. -

Connecticut College Digital Commons @ Connecticut College Linda Lear Center for Special Collections & Alumni News Archives

Connecticut College Digital Commons @ Connecticut College Linda Lear Center for Special Collections & Alumni News Archives Fall 1976 Connecticut College Alumni Magazine, Fall 1976 Connecticut College Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/alumnews Recommended Citation Connecticut College, "Connecticut College Alumni Magazine, Fall 1976" (1976). Alumni News. Paper 196. http://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/alumnews/196 This Magazine is brought to you for free and open access by the Linda Lear Center for Special Collections & Archives at Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Alumni News by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author. The Connecticut College Alumni Magazine Kurt Vonnegut dedicates the new library EDITORIAL BOARD: Allen T. Carroll '73 Editor (R.F.D. 3, EXECUTIVE BOARD OF THE ALUMNI ASSOCIATION Colchester, Ct. 06415), Marion Vilbert Clark '24 Cassandra GOBS Simonds '55, President / Mariana Parcells Class Notes Editor, Elizabeth Damerel Gongaware '26 Wagoner '44, First Vice-President / Mary Lee Min~er Assistant Editor, Cassandra Goss Simonds '55, Louise Goode '46 Second Vice-President / Britts Jo Schem Stevenson Andersen' 41 ex officio McNemar' '67, Secretary / Ann Roche Dickson '53, Treasurer CREDITS: llIustration at top of page 6 from photograph by Directors-at-Large, Ann Crocker Wheeler '34, Sara Rowe Larry Albee '74. Heckscher '69, Michael J. Farrar '73/ Alumni Trustees, . Elizabeth J. Dutton"47 Virginia Golden Kent '35, Jane Smith Official publication of the Connecticut College Association. Moody '49/ Chairman ~f the Alumni Annual Givi~ Pr?gram. -

The Poetry of Rita Dove

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Winter 1999 Language's "bliss of unfolding" in and through history, autobiography and myth: The poetry of Rita Dove Carol Keyes University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation Keyes, Carol, "Language's "bliss of unfolding" in and through history, autobiography and myth: The poetry of Rita Dove" (1999). Doctoral Dissertations. 2107. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/2107 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMi films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Young Howard the Making of a Male Lesbian a Novel by T.L. Winslow (C) Copyright 2000 by T.L. Winslow. All Rights Reserved. This

C:\younghoward\younghoward.txt Friday, June 07, 2013 2:30 PM Young Howard The Making Of A Male Lesbian A Novel by T.L. Winslow (C) Copyright 2000 by T.L. Winslow. All Rights Reserved. This novel is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the products of the author's imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. -1- C:\younghoward\younghoward.txt Friday, June 07, 2013 2:30 PM PREFACE This is my secret autobiography of my childhood. I keep it in encrypted form on my personal computer where only I can get at it. My password is pAtTypUkE. I don't want it to be published or known while I'm alive, but kept only for my private masturbation fantasies. I will supply the password to it in my will, with instructions to my lawyer to release it fifty years after my death. In case anybody cracks it, beware of the curse of Tutankhamen and respect its privacy. In the extremely unlikely event that somebody does crack it and publish it, I'm warning you: at least have the human decency to obliterate my name and label it as fiction. I make millions a year and can hire detectives and sue your ass off can't I? Labelled as fiction about a fictional character, I have plausible deniability and so do you. Humor me, okay? Note from the Editor. This document was indeed hacked and then mutilated as it circulated furiously around the Howard fan sites on the Web, with many Billy Shakespeares making anonymous additions. -

The Universal Quixote: Appropriations of a Literary Icon

THE UNIVERSAL QUIXOTE: APPROPRIATIONS OF A LITERARY ICON A Dissertation by MARK DAVID MCGRAW Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Chair of Committee, Eduardo Urbina Committee Members, Paul Christensen Juan Carlos Galdo Janet McCann Stephen Miller Head of Department, Steven Oberhelman August 2013 Major Subject: Hispanic Studies Copyright 2013 Mark David McGraw ABSTRACT First functioning as image based text and then as a widely illustrated book, the impact of the literary figure Don Quixote outgrew his textual limits to gain near- universal recognition as a cultural icon. Compared to the relatively small number of readers who have actually read both extensive volumes of Cervantes´ novel, an overwhelming percentage of people worldwide can identify an image of Don Quixote, especially if he is paired with his squire, Sancho Panza, and know something about the basic premise of the story. The problem that drives this paper is to determine how this Spanish 17th century literary character was able to gain near-univeral iconic recognizability. The methods used to research this phenomenon were to examine the character´s literary beginnings and iconization through translation and adaptation, film, textual and popular iconography, as well commercial, nationalist, revolutionary and institutional appropriations and determine what factors made him so useful for appropriation. The research concludes that the literary figure of Don Quixote has proven to be exceptionally receptive to readers´ appropriative requirements due to his paradoxical nature. The Quixote’s “cuerdo loco” or “wise fool” inherits paradoxy from Erasmus of Rotterdam’s In Praise of Folly.