Transcendence and Immanence: Deciphering Their Relation Through the Transcendentals in Aquinas and Kant

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What to Be Realist About in Linguistic Science

What to be realist about in linguistic science Geoffrey K. Pullum School of Philosophy, Psychology and Language Sciences University of Edinburgh This paper was presented at a workshop entitled ‘Foundation of Linguistics: Languages as Abstract Objects’ at the Technische Universitat¨ Carolo-Wilhelmina in Braunschweig, Germany, June 25–28. At the end of his viva, Hilary Putnam asked him, “And tell us, Mr. Boolos, what does the analytical hierarchy have to do with the real world?” Without hesitating Boolos replied, “It’s part of it.” [From the Wikipedia article on the MIT logician George Boolos] Prefatory remarks on realism I need to begin by clarifying what is meant (or at least, what I and others have meant) by ‘realism’. That such clarification is necessary is indicated by the fact that the subtitle of this workshop (‘Lan- guages as Abstract Objects’) clearly pays homage to Katz (1981) (Language and Other Abstract Objects). What the late Jerrold J. Katz meant by the word ‘realism’ does not comport with the usage of most philosophers. Katz shows little interest in defining his terms. He barely even waves a hand in that direc- tion. The third page of Language and Other Abstract Objects book announces that he has had an epiphany: there is “an alternative to both the American structuralists’ and the Chomskian concep- tion of what grammars are theories of, namely, the Platonic realist view that grammars are theories of abstract objects (sentences)” (Katz 1981, 3). Neither ‘Platonic’ nor ‘realist’ are analysed, expli- cated, or even glossed at this point. ‘Platonic realism’ is thereafter abbreviated to ‘Platonism’ and simply assumed to be understood. -

Beauty As a Transcendental in the Thought of Joseph Ratzinger

The University of Notre Dame Australia ResearchOnline@ND Theses 2015 Beauty as a transcendental in the thought of Joseph Ratzinger John Jang University of Notre Dame Australia Follow this and additional works at: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses Part of the Philosophy Commons COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 WARNING The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice. Publication Details Jang, J. (2015). Beauty as a transcendental in the thought of Joseph Ratzinger (Master of Philosophy (School of Philosophy and Theology)). University of Notre Dame Australia. https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses/112 This dissertation/thesis is brought to you by ResearchOnline@ND. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of ResearchOnline@ND. For more information, please contact [email protected]. School of Philosophy and Theology Sydney Beauty as a Transcendental in the Thought of Joseph Ratzinger Submitted by John Jang A thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Philosophy Supervised by Dr. Renée Köhler-Ryan July 2015 © John Jang 2015 Table of Contents Abstract v Declaration of Authorship vi Acknowledgements vii Introduction 1 Structure 3 Method 5 PART I - Metaphysical Beauty 7 1.1.1 The Integration of Philosophy and Theology 8 1.1.2 Ratzinger’s Response 11 1.2.1 Transcendental Participation 14 1.2.2 Transcendental Convertibility 18 1.2.3 Analogy of Being 25 PART II - Reason and Experience 28 2. -

On Moral Understanding

COMMENTTHE COLLEGE NEWSLETTER ISSUE NO 147 | MAY 2003 TOM WHIPPS On Moral Understanding DNA pioneers: The surviving members of the King’s team, who worked on the discovery of the structure of DNA 50 years ago, withDavid James Watson, K Levytheir Cambridge ‘rival’ at the time. From left Ray Gosling, Herbert Wilson, DNA at King’s: DepartmentJames Watson and of Maurice Philosophy Wilkins King’s College the continuing story University of London Prize for his contribution – and A day of celebrations their teams, but also to subse- quent generations of scientists at ver 600 guests attended a cant scientific discovery of the King’s. unique day of events celeb- 20th century,’ in the words of Four Nobel Laureates – Mau- Orating King’s role in the 50th Principal Professor Arthur Lucas, rice Wilkins, James Watson, Sid- anniversary of the discovery of the ‘and their research changed ney Altman and Tim Hunt – double helix structure of DNA on the world’. attended the event which was so 22 April. The day paid tribute not only to oversubscribed that the proceed- Scientists at King’s played a King’s DNA pioneers Rosalind ings were relayed by video link to fundamental role in this momen- Franklin and Maurice Wilkins – tous discovery – ‘the most signifi- who went onto win the Nobel continued on page 2 2 Funding news | 3 Peace Operations Review | 5 Widening participation | 8 25 years of Anglo-French law | 11 Margaret Atwood at King’s | 12 Susan Gibson wins Rosalind Franklin Award | 15 Focus: School of Law | 16 Research news | 18 Books | 19 KCLSU election results | 20 Arts abcdef U N I V E R S I T Y O F L O N D O N A C C O M M O D A T I O N O F F I C E ACCOMMODATION INFORMATION - FINDING SOMEWHERE TO LIVE IN THE PRIVATE SECTOR Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy WARNING: Under no circumstances inshould the this University document be of taken London as providing legal advice. -

CALCULUS: Early Transcendentals, 6E

Sheet1 Math1161.01= Math 1161.02= Regular FEH Engineering Mathematics Semester I : 5 Credit hours (Autumn semester) Textbook sections are from J. Stewart: CALCULUS: Early Transcendentals, 6E Lecture Days Section# # of pages Subject Week 1 3 2.1 5 The Tangent and Velocity Problems 2.2 9 The Limit of a Function 2.3 7 Calculating Limits Using the Limit Laws Week 2 3 2.4 8 Precise Definition of a Limit 2.5 8 Continuity 2.6 11 Limits at Infinity; Horizontal Asymptodes 2.7 7 Tangents, Velocities, and Other Rates of Change Week 3 3 2.8 8 The Derivative as a Function 3.1 8 Derivatives of Polynomials and of Exponentials 3.2 4 The Product and Quotient Rules 3.3 5 Derivatives of Trigonometric Functions Week 4 3 3.4 5 The Chain Rule 3.5 6 Implicit Differentiation 3.6 5 Derivatives of logarithmic functions 3.7 9 Rates of change in the sciences Week 5 3 Review Midterm I 3.8 6 Exponential growth and decay 3.9 4 Related rates Week 6 3 3.10 5 Linear Approximations and Differentials 3.11 5 Hyperbolic Functions 4.1 6 Maximum and Minimum Values 4.2 5 The Mean Value Theorem Week 7 3 4.3 8 How Derivatives Affect the Shape of a Graph 4.4 6 Indeterminate Forms and L'Hospital's Rule 4.5 7 Summary of Curve Sketching 4.6 5 Graphing with Calculus and Calculators Week 8 3 4.7 6 Optimization Problems 4.9 5 Antiderivatives Midterm II 5.1 9 Areas and Distances Week 9 3 5.2 10 The Definite Integral 5.3 9 The Fundamental Theorem of Calculus 5.4 6 Indefinite Integral and the Net Change Theorem Week10 3 5.5 6 The Substitution Rule 6.1 5 Area between Curves 6.2 8 Volumes -

Socrates, Phil Inquiry & the Elenctic Method (F11new)

PLATO, PHILOSOPHICAL INQUIRY & THE ELENCTIC METHOD All human beings, by their nature, desire understanding. — Aristotle, Metaphysics (Book 1) The safest general characterisation of the European philosophical tradition is that it consists of a series of footnotes to Plato. — Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality The elenctic method (part 1): on Meno’s enumerative THE BIG IDEAS TO MASTER definition of (human) virtue • Theory • Socratic humility On Platonic realism & Socratic definitions. According to Plato, a • The elenctic method central part of philosophical inquiry involves an attempt to • Platonic realism understand the Forms. This implies that he is committed the view • Platonic Forms we will call Platonic realism, namely, the view that • Socratic definitions • Essences Platonic realism. The Forms exist. • Natural kinds vs. artefacts • Abstract vs. concrete entities So, according to this theory, Reality contains the Forms. But what • Essential vs. accidental properties are the Forms? That question is best answered as follows. Much of • Counterexample the most important research that philosophers and other scholars do • Reductio ad absurdum argument involves an attempt to answer questions of the form ‘what is x?’ • Sound argument Physicists, for instance, ask ‘what is a black hole?’; biologists ask • Valid argument ‘what is an organism?’; mathematicians ask ‘what is a right triangle?’ • The correspondence theory of truth Let us call the correct answer to a what-is-x question the Socratic • Fact definition of x. We can say, then, that physicists are seeking the Socratic definition of a black hole, biologists investigate the Socratic definition of an organism, and mathematicians look to determine the Socratic definition of a right triangle. -

CHAPTER 1 and Unexemplified Properties, Kinds, and Relations

UNIVERSALS I: METAPHYSICAL REALISM existing objects; whereas other realists believe that there are both exemplified CHAPTER 1 and unexemplified properties, kinds, and relations. The problem of universals I Realism and nominalism The objects we talk and think about can be classified in all kinds of Metaphysical realism ways. We sort things by color, and we have red things, yellow things, and blue things. We sort them by shape, and we have triangular things, circular things, and square things. We sort them by kind, and 0 Realism and nominalism we have elephants, oak trees, and paramecia. The kind of classification The ontology of metaphysical realism at work in these cases is an essential component in our experience of the Realism and predication world. There is little, if anything, that we can think or say, little, if anything, that counts as experience, that does not involve groupings of Realism and abstract reference these kinds. Although almost everyone will concede that some of our 0 Restrictions on realism - exemplification ways of classifying objects reflect our interests, goals, and values, few 0 Further restrictions - defined and undefined predicates will deny that many of our ways of sorting things are fixed by the 0 Are there any unexemplified attributes? objects themselves.' It is not as if we just arbitrarily choose to call some things triangular, others circular, and still others square; they are tri- angular, circular, and square. Likewise, it is not a mere consequence of Overview human thought or language that there are elephants, oak trees, and paramecia. They come that way, and our language and thought reflect The phenomenon of similarity or attribute agreement gives rise to the debate these antecedently given facts about them. -

Black Existential Philosophy: Truth in Virtue of Self-Discovery James B

Duquesne University Duquesne Scholarship Collection Electronic Theses and Dissertations Spring 2014 Black Existential Philosophy: Truth in Virtue of Self-Discovery James B. Haile Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/etd Recommended Citation Haile, J. (2014). Black Existential Philosophy: Truth in Virtue of Self-Discovery (Doctoral dissertation, Duquesne University). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/614 This Immediate Access is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BLACK EXISTENTIAL PHILOSOPHY: TRUTH IN VIRTUE OF SELF‐ DISCOVERY A Dissertation Submitted to McAnulty College and Graduate School of Liberal Arts Duquesne University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By James B. Haile, III May 2014 i Copyright by James B. Haile, III 2014 ii BLACK EXISTENTIAL PHILOSOPHY: TRUTH IN VIRTUE OF SELF‐DISCOVERY By James B. Haile, III Approved June 23, 2013 _______________________________________ ________________________________________ James Swindal Michael Harrington Professor of Philosophy Associate Professor of Philosophy (Committee Chair) (Committee Member) ______________________________________ Jerry R. Ward Professor of English Retired, Dillard University (Committee Member) _____________________________________ _____________________________________ -

Notes on God's Transcendental Properties 1.Pdf

The “Infinity” of the Transcendental Properties of God The “properties” of God, the so-called transcendental properties, which traditionally include being, goodness and truth, as well as others like beauty, are paradigm examples of properties that are not “measurable.” They are not properties that are amenable to extensive measure as that idea is understood in modern science (see notes on extensive measure). That is, they are not properties for which it is possible to define an experimental unit and an experimental operation of “adding” one unit to another (called concatenation in measure theory). The best that is available for “quantities” of masses like being, goodness, truth, and beauty is that they may be put in to an ordering of more to less without exact numerical evaluation. It follows that it is not possible to apply the modern mathematical notion of “the infinite” to such “quantities” because the modern notion presupposes that it is possible to count – apply numbers to – the quantities that are being measured. It also follows that the only sense in which the properties of God would be infinite in a sense that is appropriate to a non-numerical ordering. In God’s being, truth, goodness, etc. are infinite only in the sense that the quantity of the properties that God possesses is the greatest possible. Below are internet texts explaining the transcendental properties. See also Thomas Aquinas, De Veritate, Q1, Articles 1‐3 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transcendentals Transcendentals From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search This article is about the transcendental properties of being, for other articles about transcendence; see Transcendence (disambiguation). -

Universals.Pdf

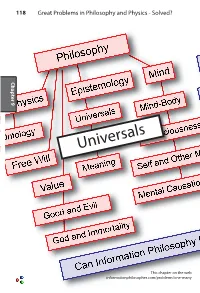

118 Great Problems in Philosophy and Physics - Solved? Chapter 9 Chapter Universals This chapter on the web informationphilosopher.com/problems/one-many Universals 119 Universals A “universal” in metaphysics is a property or attribute that is shared by many particular objects (or concepts). It has a subtle relationship to the problem of the one and the many. It is also the question of ontology.1 What exists in the world? Ontology is intimately connected with epistemology - how can we know what exists in the world? Knowledge about objects consists in describing the objects with properties and attributes, including their relations to other objects. Rarely are individual properties unique to an individual object. Although a “bundle of properties” may uniquely charac- 9 Chapter terize a particular individual, most properties are shared with many individuals. The “problem of universals” is the existential status of a given shared property. Does the one universal property exist apart from the many instances in particular objects? Plato thought it does. Aristotle thought it does not. Consider the property having the color red. Is there an abstract concept of redness or “being red?” Granted the idea of a concept of redness, in what way and where in particular does it exist? Nomi- nalists (sometimes called anti-realists) say that it exists only in the particular instances, and that redness is the name of this property. Conceptualists say that the concept of redness exists only in the minds of those persons who have grasped the concept of redness. They might exclude color-blind persons who cannot perceive red. -

1. Armstrong and Aristotle There Are Two Main Reasons for Not

RECENSIONI&REPORTS report ANNABELLA D’ATRI DAVID MALET ARMSTRONG’S NEO‐ARISTOTELIANISM 1. Armstrong and Aristotle 2. Lowe on Aristotelian substance 3. Armstrong and Lowe on the laws of nature 4. Conclusion ABSTRACT: The aim of this paper is to establish criteria for designating the Systematic Metaphysics of Australian philosopher David Malet Armstrong as neo‐ Aristotelian and to distinguish this form of weak neo‐ Aristotelianism from other forms, specifically from John Lowe’s strong neo‐Aristotelianism. In order to compare the two forms, I will focus on the Aristotelian category of substance, and on the dissimilar attitudes of Armstrong and Lowe with regard to this category. Finally, I will test the impact of the two different metaphysics on the ontological explanation of laws of nature. 1. Armstrong and Aristotle There are two main reasons for not considering Armstrong’s Systematic Metaphysics as Aristotelian: a) the first is a “philological” reason: we don’t have evidence of Armstrong reading and analyzing Aristotle’s main works. On the contrary, we have evidence of Armstrong’s acknowledgments to Peter Anstey1 for drawing his attention to the reference of Aristotle’s theory of truthmaker in Categories and to Jim Franklin2 for a passage in Aristotle’s Metaphysics on the theory of the “one”; b) the second reason is “historiographic”: Armstrong isn’t listed among the authors labeled as contemporary Aristotelian metaphysicians3. Nonetheless, there are also reasons for speaking of Armstrong’s Aristotelianism if, according to 1 D. M. Armstrong, A World of State of Affairs, Cambridge University Press, New York 1978, p. 13. 2 Ibid., p. -

HTT Introduction

1 The Transcendental Turn Sebastian Gardner Kant's influence on the history of philosophy is vast and protean. The transcendental turn denotes one of its most important forms, defined by the notion that Kant's deepest insight should not be identified with any specific epistemological or metaphysical doctrine, but rather concerns the fundamental standpoint and terms of reference of philosophical enquiry. To take the transcendental turn is not to endorse any of Kant's specific teachings, but to accept that the Copernican revolution announced in the Preface of the Critique of Pure Reason sets philosophy on a new footing and constitutes the proper starting point of philosophical reflection. The question of what precisely defines the transcendental standpoint has both historical and systematic aspects. It can be asked, on the one hand, what different construals have been put on Kant's Copernican revolution and what different historical forms the transcendental project has assumed, and on the other, how transcendental philosophy, in abstraction from its historical instances, should be defined and practised. Though separable, the two questions are best taken together. In so far as historical interest has a critical dimension, it will constantly broach systematic issues, just as any convincing account of the nature of transcendental philosophy will need to take account of the historical development. The present volume examines the history of the transcendental turn with the dual aim of elucidating the thought of individual philosophers, and of bringing into clearer view the existence of a transcendental tradition, intertwined with but distinguishable from other, more configurations in late modern philosophy. -

Causation: a Realist Approach by MICHAEL TOOLEY Oxford University Press, 1988

the chief editor with a historical survey of various views of the nature of philosophy and concludes with a short glossary of philosophical terms and a chronological table of memorable dates in philosophy and other arts and sciences from 1600 to 1960. The various chapters, with few exceptions, show a consistent fluency, clarity and readability. They are, in the main, conventional, orthodox, traditional, neutral, impartial, fair and safe, though, naturally, the expert reader will have disagreements with specific points. Usually a clear distinction is made, where appropriate, between analytic and normative considerations of the topic and something is said on each. There is only a little overlap between chapters. The title is misleading. Innumerable topics are not discussed at all. No essay is devoted to any philosopher, major or minor, as such, though frequent references are made to many in passing, since, in fact, the vast majority of the chapters consist of semi-historical, semi-critical surveys of the standard views on the topic under consideration. This fault might be remedied by using the book in conjunction with the well known Critical History of Western Philosophy edited by O’Connor. The book lacks the vast range of Edwards’ Encyclopaedia ofPhilosophy; and, though each chapter is usually longer and more widely cast than most of his entries, the total is far less comprehensive. Just because each chapter tries to cover too much ground in too wide a sweep, I doubt it will be very intelligible as a reference book to the class of reader - “the general reader . the sixth former . university students ofphilosophy .