Samson Interview with Brett Bailey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spirit of Burgas Is Again a Contender for the Festival “Oscars”

Spirit of Burgas is Again a Contender for the Festival “Oscars” Wednesday, 22 September 2010 The best music festival in Bulgaria - SPIRIT of Burgas was again nominated in the category of Best Overseas Festival in the UK Festival Awards. It has the chance to win the prize in a competition with major events such as the Amsterdam Dance Event, Global Gathering, Exit, Sziget, etc. Level of the festival in the music world these awards are the Oscars equivalent in film. Support SPIRIT of Burgas at: http://www.festivalawards.com After a short and quick online registration, you can give your vote for the Bulgarian festival by just one click and thus help in making better image of our country to Europe and the world. What's more - every vote gives you the chance to get 2 tickets for each festival! UK Festival Awards will be handed out at a gala ceremony in London futuristic room "O2" on November 18. Until then, vote for the SPIRIT of Burgas! In its third edition, the festival showed that each year it evolves and how it will not be noticed by the European music community. The festival continues to grow each year. It was nominated for "Best European Festival" of the UK Festival Awards in 2008 and in the category "Best Overseas Festival" in 2009. In the same year the Times of London newspaper named SPIRIT of Burgas as one of the Top 20 European Music Festivals . With its latest edition, SPIRIT of Burgas proved that its quality constantly improves. The presence of such artists as The Prodigy, Apollo 440, DJ Shadow, Unkle, Serj Tankian, Gorillaz Sound System and Grandmaster Flash gathered a record crowd on the beach of Bourgas this summer. -

Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: an Analysis Into Graphic Design's

Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: An Analysis into Graphic Design’s Effectiveness at Conveying Music Genres by Vivian Le A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Accounting and Business Information Systems (Honors Scholar) Presented May 29, 2020 Commencement June 2020 AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Vivian Le for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Accounting and Business Information Systems presented on May 29, 2020. Title: Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: An Analysis into Graphic Design’s Effectiveness at Conveying Music Genres. Abstract approved:_____________________________________________________ Ryann Reynolds-McIlnay The rise of digital streaming has largely impacted the way the average listener consumes music. Consequentially, while the role of album art has evolved to meet the changes in music technology, it is hard to measure the effect of digital streaming on modern album art. This research seeks to determine whether or not graphic design still plays a role in marketing information about the music, such as its genre, to the consumer. It does so through two studies: 1. A computer visual analysis that measures color dominance of an image, and 2. A mixed-design lab experiment with volunteer participants who attempt to assess the genre of a given album. Findings from the first study show that color scheme models created from album samples cannot be used to predict the genre of an album. Further findings from the second theory show that consumers pay a significant amount of attention to album covers, enough to be able to correctly assess the genre of an album most of the time. -

Queens of the Stone Age Are: Joshua Homme, Troy Van Leeuwen, Dean Fertita, Michael Shuman

Queens of the Stone Age are: Joshua Homme, Troy Van Leeuwen, Dean Fertita, Michael Shuman …Like Clockwork Release date June 4th, 2013 (US) LABEL • …Like Clockwork is the first QOTSA release with new label partner, Matador Records – which is part of the Beggars Group, the largest independent label group in the world. PRODUCTION • …Like Clockwork was recorded at Joshua Homme’s Pink Duck Studios in Burbank, CA • All Songs produced by Joshua Homme and QOTSA except …Like Clockwork, produced by Joshua Homme and James Lavelle • Engineered by Mark Rankin, with additional engineering by Alain Johannes and Justin Smith • All songs mixed by Mark Rankin, except “Fairweather Friends” mixed by Joe Barresi • All lyrics by Joshua Homme • Mastered by Gavin Lurssen of Lurssen Mastering, Los Angeles, CA ADDITIONAL PERFORMERS • DRUMMERS Joey Castillo, Dave Grohl, Jon Theodore o After Joey left the band, Dave came in to play on the remaining songs. § Joey Castillo performs on “Keep Your Eyes Peeled” - “ I Sat by the Ocean” - “The Vampyre of Time and Memory”- “Kalposia” § Dave Grohl performs on “My God Is The Sun” - “If I Had a Tail” - “Smooth Sailing” “Fairweather Friends” - “I Appear Missing” § Jon Theodore is the new touring drummer of QOTSA, and performs on “…Like Clockwork” • Jake Shears (Scissor Sisters) appears on “Keep Your Eyes Peeled” o Homme has previously worked with the front man by appearing as the spokesperson in an infomercial for the Scissor Sisters 2012 release “Magic Hour” http://youtu.be/aw60b-wk9MA • Mark Lanegan, Nick Oliveri and Alex -

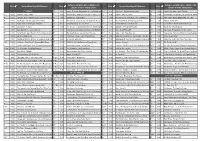

Price Record Store Day 2019 Releases Price Follow Us on Twitter

Follow us on twitter @PiccadillyRecs for Follow us on twitter @PiccadillyRecs for Price ✓ Record Store Day 2019 Releases Price ✓ Price ✓ Record Store Day 2019 Releases Price ✓ updates on items selling out etc. updates on items selling out etc. 7" SINGLES 7" 14.99 Queen : Bohemian Rhapsody/I'm In Love With My Car 12" 22.99 John Grant : Remixes Are Also Magic 12" 9.99 Lonnie Liston Smith : Space Princess 7" 12.99 Anderson .Paak : Bubblin' 7" 13.99 Sharon Ridley : Where Did You Learn To Make Love The 12" Way You 11.99Do Hipnotic : Are You Lonely? 12" 10.99 Soul Mekanik : Go Upstairs/Echo Beach (feat. Isabelle Antena) 7" 16.99 Azymuth : Demos 1973-75: Castelo (Version 1)/Juntos Mais 7" Uma Vez9.99 Saint Etienne : Saturday Boy 12" 9.99 Honeyblood : The Third Degree/She's A Nightmare 12" 11.99 Spirit : Spirit - Original Mix/Zaf & Phil Asher Edit 7" 10.99 Bad Religion : My Sanity/Chaos From Within 7" 12.99 Shit Girlfriend : Dress Like Cher/Socks On The Beach 12" 13.99 Hot 8 Brass Band : Working Together E.P. 12" 9.99 Stalawa : In East Africa 7" 9.99 Erykah Badu & Jame Poyser : Tempted 7" 10.99 Smiles/Astronauts, etc : Just A Star 12" 9.99 Freddie Hubbard : Little Sunflower 12" 10.99 Joe Strummer : The Rockfield Studio Tracks 7" 6.99 Julien Baker : Red Door 7" 15.99 The Specials : 10 Commandments/You're Wondering Now 12" 15.99 iDKHOW : 1981 Extended Play EP 12" 19.99 Suicide : Dream Baby Dream 7" 6.99 Bang Bang Romeo : Cemetry/Creep 7" 10.99 Vivian Stanshall & Gargantuan Chums (John Entwistle & Keith12" Moon)14.99 : SuspicionIdles : Meat EP/Meta EP 10" 13.99 Supergrass : Pumping On Your Stereo/Mary 7" 12.99 Darrell Banks : Open The Door To Your Heart (Vocal & Instrumental) 7" 8.99 The Straight Arrows : Another Day In The City 10" 15.99 Japan : Life In Tokyo/Quiet Life 12" 17.99 Swervedriver : Reflections/Think I'm Gonna Feel Better 7" 8.99 Big Stick : Drag Racing 7" 10.99 Tindersticks : Willow (Feat. -

North Carolina Folklore

VOLUME X DECEMBER 1962 NUMBER 2 NORTH CAROLINA FOLKLORE ARTHUR PALMER HUDSON Editor • e CONTENTS•• ~ Page 1 CAROLINA COURTSHIP AND MARRIAGE IN THE 1840 s1 John Q. Anderson. • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • A NOTE ON TOBACCO MAGIC, Willian Joseph Free ••• ·\. 9 A TRIP TO TABLE ROCK DURING 1812, Joseph Rutherford, Edited by ..... M-s. Albert E. Skaggs • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 11 A FORGOTTEN POEM BY A. B. LONGSTREET, Allen Coboniss ••• 14 A GRANDFATHER'S TALES OF THE LOWERY BROTHERS, Susan Holly Woodward. • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 17 THE NEW YEAR'S SHOOT AT CHERRYVILLE, Donald W. Crowley • 21 FRANKIE SILVER, Elaine Penninger. • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 26 PROGRAM OF THE DECEMBER 1962 MEETING OF THE FOLKLORE SOCIETY 29 CHEERS FOR ST . MARY'S. • • • • • • 30 SOME BOOK NOTICES, A. P. Hudson • • 31 A Publication of THE NORTH CAROLINA FOLKLORE SOCIETY and UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA FOLKLORE COUNCIL Chapel Hill NORTH CAROLINA FOLKLORE Every reader is invited ta submit items or manuscripts far publication, preferably of the length of those in this issue. Subscriptions, other business communications, and contributions should be sent ta Arthur Palmer Hudson Editor of --------North Caroline Folklore The University of North Carolina 710 Greenwood Road Chapel Hill, North Carolina. Annual subscription, $2 far adults, $1 far students (including membership in The l'Jorth Carolina folklore Society). Price of this number, $1. THE NORTH CAROLINA FOLKLORE SOCIETY Richard Walser, Raleigh, President General John 0. F. Phillips, Raleigh, 1 Vice President Miss Ruth Jewell, Raleigh, 2 Vice President Arthur Palmer Hudson, Chapel Hil I, Secretary-Treasurer The North Carolina Folklore Society was organized .in 1912, ta encourage the collection, study, and publication of North Carolina Folklore. -

The Man from UNKLE: James Lavelle, Camden, North London, 2017

The man from UNKLE: James Lavelle, Camden, North London, 2017. Celebrating the wildc PHOTOGRAPHS RACHAEL WRIGHT LAVELLE James Lavelle was the boy wonder who, as the It’s been a long, intense journey, hence founder of the Mo’ Wax label, launched DJ Shadow the title of the powerful new UNKLE album, 1 and invented trip-hop. But it was as the director of his The Road: Part . Raiding the archives for Mo’ Wax’s 21st anniversary in 2013, great collaborative project UNKLE that he proved himself curating the Meltdown festival in 2014, to be a visionary lightning rod, bringing Thom Yorke, and participating in a new documentary, Artist & Repertoire, have all conspired to Mike D and Richard Ashcroft together. By 2003, though, make Lavelle reassess his past and ask he was nearly bankrupt. And then the trouble really himself why he makes music. started. Dorian Lynskey hears his story. “The last 13 years have been fucking tough financially,” he says over cartons of n February 1998, wonder of British music. He was the hipster Korean food in his manager’s office in James Lavelle geek whose Mo’ Wax label, home to DJ Camden. “In one way I’m probably insane to celebrated his Shadow and his own UNKLE project, was keep doing what I do. Anybody rational 24th birthday the impeccably cool junction box for an would have stopped trying to do UNKLE with a party at international network of musicians, DJs and years ago.” He laughs oddly. “I’ve put myself I London’s Met Bar designers. When he was negotiating a deal through quite extreme situations, both in the company of with A&M in 1995, his gutsy deal-breaker was financially and emotionally. -

Album Top 1000 2021

2021 2020 ARTIEST ALBUM JAAR ? 9 Arc%c Monkeys Whatever People Say I Am, That's What I'm Not 2006 ? 12 Editors An end has a start 2007 ? 5 Metallica Metallica (The Black Album) 1991 ? 4 Muse Origin of Symmetry 2001 ? 2 Nirvana Nevermind 1992 ? 7 Oasis (What's the Story) Morning Glory? 1995 ? 1 Pearl Jam Ten 1992 ? 6 Queens Of The Stone Age Songs for the Deaf 2002 ? 3 Radiohead OK Computer 1997 ? 8 Rage Against The Machine Rage Against The Machine 1993 11 10 Green Day Dookie 1995 12 17 R.E.M. Automa%c for the People 1992 13 13 Linkin' Park Hybrid Theory 2001 14 19 Pink floyd Dark side of the moon 1973 15 11 System of a Down Toxicity 2001 16 15 Red Hot Chili Peppers Californica%on 2000 17 18 Smashing Pumpkins Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness 1995 18 28 U2 The Joshua Tree 1987 19 23 Rammstein Muaer 2001 20 22 Live Throwing Copper 1995 21 27 The Black Keys El Camino 2012 22 25 Soundgarden Superunknown 1994 23 26 Guns N' Roses Appe%te for Destruc%on 1989 24 20 Muse Black Holes and Revela%ons 2006 25 46 Alanis Morisseae Jagged Liale Pill 1996 26 21 Metallica Master of Puppets 1986 27 34 The Killers Hot Fuss 2004 28 16 Foo Fighters The Colour and the Shape 1997 29 14 Alice in Chains Dirt 1992 30 42 Arc%c Monkeys AM 2014 31 29 Tool Aenima 1996 32 32 Nirvana MTV Unplugged in New York 1994 33 31 Johan Pergola 2001 34 37 Joy Division Unknown Pleasures 1979 35 36 Green Day American idiot 2005 36 58 Arcade Fire Funeral 2005 37 43 Jeff Buckley Grace 1994 38 41 Eddie Vedder Into the Wild 2007 39 54 Audioslave Audioslave 2002 40 35 The Beatles Sgt. -

Cyclic Defrost Issue 8

ISSUE 8 CDITORIAL CONTENTS Welcome to issue 8 and the end of our second year. It has been a 4 COVER DESIGNER: MARK GOWING upward curve since Sonar last year, and Cyclic Defrost is back at Sonar by Bim Ricketson this year and continuing to build connections with Europe. Good Australian electronic music has been starting to spread more broadly 6 PURDY overseas and the next couple of months sees the number of Australian by Sebastian Chan PO Box a2073 acts overseas growing substantially. Sydney South 10 CITY CITYCITY This issue’s cover art is by Sydney-based graphic designer Mark NSW 1235 Australia by Bob Baker Fish Gowing, whose logos and other work should be familiar to a lot of We welcome your contributions 11 ANTHONY PATERAS Sydney locals. Inside you’ll find interviews with the old guard – Kevin and contact: by Bob Baker Fish Purdy, Coldcut, Tortoise’s Jeff Parker, as well as the spring chickens – [email protected] Perth’s IDM youngster Pablo Dali, Melbourne post-rockers City City www.cyclicdefrost.com 14 PABLO DALI by melinda Taylor City, Lali Puna and Anthony Pateras. After the continual hectoring ISSUE 9 DEADLINE: AUGUST 12, 2004 about MP3 politics in previous issues, one of our writers, Vaughan 16 COLDCUT Healey finally got hold of an iPod for a fortnight and went about trying Publisher & Editor-in-Chief by Clark Nova to learn the art of iPod krumping, and Degrassi gives solid holiday tips. Sebastian Chan 18 LALI PUNA By the time you’ve waded through those in this 44 page bumper issue, Art Director & Co-Editor by Peter Hollo you’ll come to the treasure chest of reviews and this issue’s sleeve Dale Harrison 20 TORTOISE design look at embossing. -

A Proposed Typology of Sampled Material Within Electronic Dance Music1 Feature Article Robert Ratcliffe Manchester Metropolitan University (UK)

A Proposed Typology of Sampled Material within Electronic Dance Music1 Feature Article Robert Ratcliffe Manchester Metropolitan University (UK) Abstract The following article contains a proposed typology of sampled material within electronic dance music (EDM). The typology offers a system of classification that takes into account the sonic, musical and referential properties of sampled elements, while also considering the technical realisation of the material and the compositional intentions of the artist, producer or DJ. Illustrated with supporting examples drawn from a wide variety of artists and sub-genres, the article seeks to address the current lack of research on the subject of sample-based composition and production, and provides a framework for further discussion of EDM sampling practices. In addition, it demonstrates how concepts and terminology derived from the field of electroacoustic music can be successfully applied to the study and analysis of EDM, resulting in an expanded analytical and theoretical vocabulary. Keywords: EDM, sample, sampling, musical borrowing, production, composition, electroacoustic, mimesis, transcontextuality, spectromorphology, source bonding Robert Ratcliffe is an internationally recognised composer, sonic artist, EDM musicologist and performer. He completed a PhD in composition and musicology funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council at Keele University, UK. He has developed a hybrid musical language and compositional technique through the cross-fertilisation of art music and electronic -

TRACES a 7 Fingers Production

PHYSICAL THEATER TRACES A 7 Fingers Production College of Charleston Sottile Theatre June 6 at 7:00pm; June 7, 8, and 9 at 8:00pm; June 9 and 10 at 2:00pm Creative Direction Les 7 Doigts de la Main/7 Fingers Direction and Choreography Shana Carroll, Gypsy Snider Acrobatic Designer Sébastien Soldevila Lights Nol van Genuchten Costumes Manon Desmarais Set & Props Original Design Flavia Hevia Set & Props Adaptation/Music & Soundscape/Video Les 7 Doigts de la Main/7 Fingers Prop Adaptation Bruno Tassé Head Coach (Acrobatics) Jerôme Le Baut Aerial Strap Isabelle Chassé Hand Balancing Samuel Tétreault Skateboards Yann Fily-Paré Single Wheel Ethan Law Piano Sophie Houle Cast Mason Ames Valérie Benôit-Charbonneau Mathieu Cloutier Bradley Henderson Philippe Normand-Jenny Tarek Rammo Xia Zhengqi Due to the physical demands of circus arts performances, the artists in each performance are subject to change. Presented by Fox Theatricals Tom Gabbard Amanda Dubois The Denver Center for the Performing Arts Nassib El-Husseini and Tom Lightburn Produced for Fox Theatricals by Kristin Caskey Mike Isaacson Advertising and Marketing aka Tour Marketing and Publicity Allied Live, LLC NYC Press Representation The Hartman Group General Management DR Theatrical Management PERFORMED WITHOUT AN INTERMISSION. PLEASE BE ADVISED THAT A STROBE LIGHT IS USED IN THIS PRODUCTION. Support provided by the Albert Sottile Foundation and an award from the National Endowment for the Arts. Traces was originally co-produced by Centre National des Arts – Ottawa with the support of partners Conseil des Arts du Canada and Conseil des Arts et Lettres du Québec. 72 PHYSICAL THEATER TRACES ABOUT 7 FINGERS THE COMPANY What do you think of when you hear the word “circus”? For most people it’s a blur of high-wire stunts, dancing animals, and MASON AMES (Artist) moved to Montreal from New peanuts. -

アーティスト 商品名 フォーマット 発売日 商品ページ 555 Solar Express CD 2013/11/13

【SOUL/CLUB/RAP】「怒涛のサプライズ ボヘミアの狂詩曲」対象リスト(アーティスト順) アーティスト 商品名 フォーマット 発売日 商品ページ 555 Solar Express CD 2013/11/13 https://tower.jp/item/3319657 1773 サウンド・ソウルステス(DIGI) CD 2010/6/2 https://tower.jp/item/2707224 1773 リターン・オブ・ザ・ニュー CD 2009/3/11 https://tower.jp/item/2525329 1773 Return Of The New (HITS PRICE) CD 2012/6/16 https://tower.jp/item/3102523 1773 RETURN OF THE NEW(LTD) CD 2013/12/25 https://tower.jp/item/3352923 2562 The New Today CD 2014/10/23 https://tower.jp/item/3729257 *Groovy workshop. Emotional Groovin' -Best Hits Mix- mixed by *Groovy workshop. CD 2017/12/13 https://tower.jp/item/4624195 100 Proof (Aged in Soul) エイジド・イン・ソウル CD 1970/11/30 https://tower.jp/item/244446 100X Posse Rare & Unreleased 1992 - 1995 Mixed by Nicky Butters CD 2009/7/18 https://tower.jp/item/2583028 13 & God Live In Japan [Limited] <初回生産限定盤>(LTD/ED) CD 2008/5/14 https://tower.jp/item/2404194 16FLIP P-VINE & Groove-Diggers Presents MIXCHAMBR : Selected & Mixed by 16FLIP <タワーレコード限定> CD 2015/7/4 https://tower.jp/item/3931525 2 Chainz Collegrove(INTL) CD 2016/4/1 https://tower.jp/item/4234390 2000 And One Voltt 02 CD 2010/2/27 https://tower.jp/item/2676223 2000 And One ヘリタージュ CD 2009/2/28 https://tower.jp/item/2535879 24-Carat Black Ghetto : Misfortune's Wealth(US/LP) Analog 2018/3/13 https://tower.jp/item/4579300 2Pac (Tupac Shakur) TUPAC VS DVD 2004/11/12 https://tower.jp/item/1602263 2Pac (Tupac Shakur) 2-PAC 4-EVER DVD 2006/9/2 https://tower.jp/item/2084155 2Pac (Tupac Shakur) Live at the house of blues(BRD) Blu-ray 2017/11/20 https://tower.jp/item/4644444 -

Simplicity Two Thousand (M

ELECTRONICA_CLUBMUSIC_SOUNDTRACKS_&_MORE URBANI AfterlifeSimplicityTwoThousand AfterlifeSimplicityTwoThousand(mixes) AirTalkieWalkie Apollo440Gettin'HighOnYourOwnSupply ArchiveNoise ArchiveYouAllLookTheSameToMe AsianDubFoundationRafi'sRevenge BethGibbons&RustinManOutOfSeason BjorkDebut BjorkPost BjorkTelegram BoardsOfCanadaMusicHasTheRightToChildren DeathInVegasScorpioRising DeathInVegasTheContinoSessions DjKrushKakusei DjKrushReloadTheRemixCollection DjKrushZen DJShadowEndtroducing DjShadowThePrivatePress FaithlessOutrospective FightClub_stx FutureSoundOfLondonDeadCities GorillazGorillaz GotanProjectLaRevanchaDelTango HooverphonicBlueWonderPowerMilk HooverphonicJackieCane HooverphonicSitDownAndListenToH HooverphonicTheMagnificentTree KosheenResist Kruder&DorfmeisterConversionsAK&DSelection Kruder&DorfmeisterDjKicks LostHighway_stx MassiveAttack100thWindow MassiveAttackHits...BlueLine&Protection MaximHell'sKitchen Moby18 MobyHits MobyHotel PhotekModusOperandi PortisheadDummy PortisheadPortishead PortisheadRoselandNYCLive Portishead&SmokeCityRareRemixes ProdigyTheCastbreeder RequiemForADream_stx Spawn_stx StreetLifeOriginals_stx TerranovaCloseTheDoor TheCrystalMethodLegionOfBoom TheCrystalMethodLondonstx TheCrystalMethodTweekendRetail TheCrystalMethodVegas TheStreetsAGrandDon'tComeforFree ThieveryCorporationDJKicks(mix1999) ThieveryCorporationSoundsFromTheThieveryHiFi ToxicLoungeLowNoon TrickyAngelsWithDirtyFaces TrickyBlowback TrickyJuxtapose TrickyMaxinquaye TrickyNearlyGod TrickyPreMillenniumTension TrickyVulnerable URBANII 9Lazy9SweetJones