SIPRI Yearbook 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Syria: "Torture Was My Punishment": Abductions, Torture and Summary

‘TORTURE WAS MY PUNISHMENT’ ABDUCTIONS, TORTURE AND SUMMARY KILLINGS UNDER ARMED GROUP RULE IN ALEPPO AND IDLEB, SYRIA Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2016 Cover photo: Armed group fighters prepare to launch a rocket in the Saif al-Dawla district of the Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons northern Syrian city of Aleppo, on 21 April 2013. (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. © Miguel Medina/AFP/Getty Images https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2016 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: MDE 24/4227/2016 July 2016 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 METHODOLOGY 7 1. BACKGROUND 9 1.1 Armed group rule in Aleppo and Idleb 9 1.2 Violations by other actors 13 2. ABDUCTIONS 15 2.1 Journalists and media activists 15 2.2 Lawyers, political activists and others 18 2.3 Children 21 2.4 Minorities 22 3. -

A Blood-Soaked Olive: What Is the Situation in Afrin Today? by Anthony Avice Du Buisson - 06/10/2018 01:23

www.theregion.org A blood-soaked olive: what is the situation in Afrin today? by Anthony Avice Du Buisson - 06/10/2018 01:23 Afrin Canton in Syria’s northwest was once a haven for thousands of people fleeing the country’s civil war. Consisting of beautiful fields of olive trees scattered across the region from Rajo to Jindires, locals harvested the land and made a living on its rich soil. This changed when the region came under Turkish occupation this year. Operation Olive Branch: Under the governance of the Afrin Council – a part of the ‘Democratic Federation of Northern Syria’ (DFNS) – the region was relatively stable. The council’s members consisted of locally elected officials from a variety of backgrounds, such as Kurdish official Aldar Xelil who formerly co-headed the Movement for a Democratic Society (TEVDEM) – a political coalition of parties governing Northern Syria. Children studied in their mother tongue— Kurdish, Arabic, or Syriac— in a country where the Ba’athists once banned Kurdish education. The local Self-Defence Forces (HXP) worked in conjunction with the People’s Protection Units (YPG) to keep the area secure from existential threats such as Turkish Security forces (TSK) and Free Syrian Army (FSA) attacks. This arrangement continued until early 2018, when Turkey unleashed a full-scale military operation called ‘ Operation Olive Branch’ to oust TEVDEM from Afrin. The Turkish government views TEVDEM and its leading party, the Democratic Union Party (PYD), as an extension of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) – listed as a terrorist organisation in Turkey. Under the pretext of defending its borders from terrorism, the Turkish government sent thousands of troops into Afrin with the assistance of forces from its allies in Idlib and its occupied Euphrates Shield territories. -

Two Routes to an Impasse: Understanding Turkey's

Two Routes to an Impasse: Understanding Turkey’s Kurdish Policy Ayşegül Aydin Cem Emrence turkey project policy paper Number 10 • December 2016 policy paper Number 10, December 2016 About CUSE The Center on the United States and Europe (CUSE) at Brookings fosters high-level U.S.-Europe- an dialogue on the changes in Europe and the global challenges that affect transatlantic relations. As an integral part of the Foreign Policy Studies Program, the Center offers independent research and recommendations for U.S. and European officials and policymakers, and it convenes seminars and public forums on policy-relevant issues. CUSE’s research program focuses on the transforma- tion of the European Union (EU); strategies for engaging the countries and regions beyond the frontiers of the EU including the Balkans, Caucasus, Russia, Turkey, and Ukraine; and broader European security issues such as the future of NATO and forging common strategies on energy security. The Center also houses specific programs on France, Germany, Italy, and Turkey. About the Turkey Project Given Turkey’s geopolitical, historical and cultural significance, and the high stakes posed by the foreign policy and domestic issues it faces, Brookings launched the Turkey Project in 2004 to foster informed public consideration, high‐level private debate, and policy recommendations focusing on developments in Turkey. In this context, Brookings has collaborated with the Turkish Industry and Business Association (TUSIAD) to institute a U.S.-Turkey Forum at Brookings. The Forum organizes events in the form of conferences, sem- inars and workshops to discuss topics of relevance to U.S.-Turkish and transatlantic relations. -

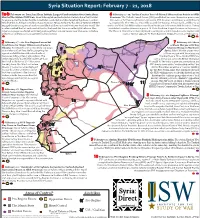

Syria SITREP Map 07

Syria Situation Report: February 7 - 21, 2018 1a-b February 10: Israel and Iran Initiate Largest Confrontation Over Syria Since 6 February 9 - 15: Turkey Creates Two Additional Observation Points in Idlib Start of the Syrian Civil War: Israel intercepted and destroyed an Iranian drone that violated Province: The Turkish Armed Forces (TSK) established two new observation points near its airspace over the Golan Heights. Israel later conducted airstrikes targeting the drone’s control the towns of Tal Tuqan and Surman in Eastern Idlib Province on February 9 and February vehicle at the T4 Airbase in Eastern Homs Province. Syrian Surface-to-Air Missile Systems (SAMS) 15, respectively. The TSK also reportedly scouted the Taftanaz Airbase north of Idlib City as engaged the returning aircraft and successfully shot down an Israeli F-16 over Northern Israel. The well as the Wadi Deif Military Base near Khan Sheikhoun in Southern Idlib Province. Turkey incident marked the first such combat loss for the Israeli Air Force since the 1982 Lebanon War. established a similar observation post at Al-Eis in Southern Aleppo Province on February 5. Israel in response conducted airstrikes targeting at least a dozen targets near Damascus including The Russian Armed Forces later deployed a contingent of military police to the regime-held at least four military positions operated by Iran in Syria. town of Hadher opposite Al-Eis in Southern Aleppo Province on February 14. 2 February 17 - 20: Pro-Regime Forces Set Qamishli 7 February 18: Ahrar Conditions for Major Offensive in Eastern a-Sham Merges with Key Ghouta: Pro-regime forces intensified a campaign 9 Islamist Group in Northern of airstrikes and artillery shelling targeting the 8 Syria: Salafi-Jihadist group Ahrar opposition-held Eastern Ghouta suburbs of Al-Hasakah a-Sham merged with Islamist group Damascus, killing at least 250 civilians. -

Congressional Testimony

Congressional Testimony “U.S. Counterterrorism Efforts in Syria: A Winning Strategy?” Thomas Joscelyn Senior Fellow, Foundation for Defense of Democracies Senior Editor, The Long War Journal Hearing before House Committee on Foreign Affairs Subcommittee on Terrorism, Nonproliferation, and Trade Washington, DC September 29, 2015 ● ● 1726 M Street NW Suite 700 Washington, DC 20036 1 Chairman Poe, Ranking Member Keating, and other members of the committee, thank you for inviting me here today to speak about America’s counterterrorism efforts in Syria. The war in Syria is exceedingly complex, with multiple actors fighting one another on the ground and foreign powers supporting their preferred proxies. Iran and Hezbollah are backing Bashar al Assad’s regime, which is also now receiving increased assistance from Russia. The Islamic State (often referred to by the acronyms ISIS and ISIL) retains control over a significant amount of Syrian territory. Despite some setbacks at the hands of the U.S.-led air coalition and Kurdish ground forces earlier this year in northern Syria, Abu Bakr al Baghdadi’s organization has not suffered anything close to a knockout blow thus far. Sunni jihadists, led by Al Nusrah Front and its closest allies, are opposed to both the Islamic State and the Assad regime. Unfortunately, they have been the most effective anti-Assad forces for some time, as could be seen in their stunning advances in the Idlib province earlier this year. Turkey, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and other nations are all sponsoring proxies in the fight. Given the complexity of the war in Syria, it should be obvious that there are no easy answers. -

1 of 4 Weekly Conflict Summary February 1-7, 2018 During The

Weekly Conflict Summary February 1-7, 2018 During the reporting period, the Turkish-led Operation Olive Branch offensive continued its advance into Afrin, the northwestern canton controlled by the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF, a US-backed, Kurdish- led organization). Elsewhere, pro-government forces continued their advance against opposition forces and ISIS fighters in the northern Hama/southern Aleppo countryside, further securing their control in the area. Following a significant uptick in attacks on both the opposition-controlled Idleb and Eastern Ghouta pockets, the UN humanitarian coordinator, Panos Moumtzis, called for an immediate one-month cessation of hostilities for the delivery of humanitarian aid. Lastly, a new opposition “operation room” has been formed in Idleb, with the stated goal of coordinating attacks against government forces. Figure 1 - Areas of control in Syria by February 7, with arrows indicating fronts of advance during the reporting period 1 of 4 Weekly Conflict Summary – February 1-7, 2018 Operation Olive Branch Operation Olive Branch forces took new territory, connecting previously isolated territories west of Raju and north of Balbal. Turkey-backed Operation Euphrates Shield forces also advanced northwest of A’zaz to take a mountaintop and village from the SDF. No gains have yet been made towards Tal Refaat along the southeastern front. There have been reports of abuses by advancing Turkish-backed, opposition Free Syrian Army (FSA) forces, including footage of Operation Olive Branch forces apparently mutilating the body of a deceased YPJ fighter (an all-female Kurdish unit within the SDF). Hundreds of US-trained YPG/SDF fighters from eastern SDF cantons arrived in Afrin this week, traveling through government-held territory to reinforce the SDF fighters on fronts against Olive Branch units. -

Der Ruf Des Dschihad Kuum Wurden Zu Einer Anlaufstelle Für Den Internationalen Dschi- Had Und Zog Tausende Kämpfer Aus Der Arabischen Welt, Aber Auch Aus Europa An

Band 13 / 2016 Band 13 / 2016 Der Sturz autoritärer Herrscher in zahlreichen arabischen Staaten schuf eine neue sicherheitspolitische Umgebung vor den Toren Europas. Diese Umbrüche führten nicht nur zu einer Aufwertung extremistischer Gruppierungen, sondern eröffneten ihnen einen noch nie dagewesenen Handlungsspielraum. Der Krieg gegen das Assad-Regime in Syrien und das entstandene Sicherheitsva- Der Ruf des Dschihad kuum wurden zu einer Anlaufstelle für den internationalen Dschi- had und zog tausende Kämpfer aus der arabischen Welt, aber auch aus Europa an. Auf diese neue Dynamik müssen Regierun- Theorie, Fallstudien und Wege aus der Radikalität gen mit vorhandenen wie auch neuen „Werkzeugen“ reagieren. Auf Grundlage der Erfahrungswerte im Umgang mit Extremismus in muslimischen und westlichen Ländern wird der Versuch unter- nommen, effektive Maßnahmen und Instrumente zur Prävention von Radikalisierung, insbesondere in Europa, zu finden. Der Ruf des Dschihad – Theorie, Fallstudien und Wege aus der Radikalität aus der und Wege Fallstudien Dschihad – Theorie, des Ruf Der ISBN: 978-3-902944-96-2 Jasmina Rupp und Walter Feichtinger (Hrsg.) 13/16 Schriftenreihe der Rupp, Feichtinger (Hrsg.) Feichtinger Rupp, Landesverteidigungsakademie Schriftenreihe der Landesverteidigungsakademie Jasmina Rupp und Walter Feichtinger (Hrsg.) Der Ruf des Dschihad Theorie, Fallstudien und Wege aus der Radikalität 13/2016 Wien, April 2016 Impressum: Medieninhaber, Herausgeber, Hersteller: Republik Österreich / Bundesministerium für Landesverteidigung und Sport -

Women Rights in Rojava- English

Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................... 2 1- Women’s Political Role in the Autonomous Administration Project in Rojava ...................................... 3 1.1 Women’s Role in the Autonomous Administration ....................................................................... 3 1.1.1 Committees for Women ......................................................................................................... 4 1.1.2 The Women’s Committee ....................................................................................................... 4 1.1.3 Women’s Associations - The “Kongreya Star” ........................................................................ 5 1.2 Women’s Representation in Political and Administrative Bodies: ................................................. 6 2. Empowering Women in the Military Field ........................................................................................... 11 2.1 The Representation of Women in the Army ................................................................................ 11 2.2 The People’s Protection Units (YPG) and Women’s Protection Units (YPJ) ................................. 12 2.2.1 The Women’s Protection Units- YPJ ..................................................................................... 12 2.2.2 The People’s Protection Units- YPG ..................................................................................... -

Local Dynamics of Conflicts in Syria and Libya

I N S I D E WARS LOCAL DYNAMICS OF CONFLICTS IN SYRIA AND LIBYA EDITED BY: LUIGI NARBONE AGNÈS FAVIER VIRGINIE COLLOMBIER This work has been published by the European University Institute, Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies, Middle East Directions. The Middle East Directions Programme encourages and supports multi-disciplinary research on the Middle East region - from Morocco to Iran, Turkey, and the Arabian Peninsula - in collaboration with researchers and research institutions from the region. Via dei Roccettini, 9 – I-50014 San Domenico di Fiesole (FI) – Italy Website: http://middleeastdirections.eu © European University Institute 2016 Editorial matter and selection © editors and responsible principal investigator 2016 Chapters © authors individually 2016 This text may be downloaded only for personal research purposes. Any additional reproduction for other purposes, whether in hard copies or electronically, requires the consent of the author(s), editor(s). If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), editor(s), the title, the year and the publisher. INSIDE WARS LOCAL DYNAMICS OF CONFLICTS IN SYRIA AND LIBYA EDITED BY: LUIGI NARBONE AGNÈS FAVIER VIRGINIE COLLOMBIER TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Luigi Narbone The Local Dynamics of Conflicts in Syria and Libya PART 1. THE SYRIAN CONFLICT Jihad Yazigi Syria’s Implosion: Political and Economic Impacts 1 Agnès Favier Local Governance Dynamics in Opposition-Controlled Areas in Syria 6 Daryous Aldarwish Local Governance under the Democratic Autonomous -

Turkey | Syria: Flash Update No. 2 Developments in Northern Aleppo

Turkey | Syria: Flash Update No. 2 Developments in Northern Aleppo, Azaz (as of 1 June 2016) Summary An estimated 16,150 individuals in total have been displaced by fighting since 27 May in the northern Aleppo countryside, with most joining settlements adjacent to the Bab Al Salam border crossing point, Azaz town, Afrin and Yazibag. Kurdish authorities in Afrin Canton have allowed civilians unimpeded access into the canton from roads adjacent to Azaz and Mare’ since 29 May in response to ongoing displacement near hostilities between ISIL and NSAGs. Some 9,000 individuals have been afforded safe passage to leave Mare’ and Sheikh Issa towns after they were trapped by fighting on 27 May; however, an estimated 5,000 civilians remain inside despite close proximity to frontlines. Humanitarian organisations continue to limit staff movement in the Azaz area for safety reasons, and some remain in hibernation. Limited, cautious humanitarian service delivery has started by some in areas of high IDP concentration. The map below illustrates recent conflict lines and the direction of movement of IDPs: United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) Coordination Saves Lives | www.unocha.org Turkey | Syria: Azaz, Flash Update No.2 Access Overview Despite a recent decline in hostilities since May 27, intermittent clashes continue between NSAGs and ISIL militants on the outskirts of Kafr Kalbien, Kafr Shush, Baraghideh, and Mare’ towns. A number of counter offensives have been coordinated by NSAGs operating in the Azaz sub district, hindering further advancements by ISIL militants towards Azaz town. As of 30 May, following the recent decline in escalations between warring parties, access has increased for civilians wanting to leave Azaz and Mare’ into areas throughout Afrin canton. -

The West's Darling in Syria

Introduction Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik German Institute for International and Security Affairs Comments The West’s Darling in Syria WP Seeking Support, the Kurdish Democratic Union Party Brandishes an Anti-Jihadist Image Khaled Yacoub Oweis S US bombings in 2015 repulsed Islamic State attacks on cities in mostly Kurdish self- rule regions called cantons in northern Syria. The three cantons, which border Turkey, are dominated by the Kurdish Democratic Union Party (PYD). The party is linked to the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), a former client of the Syrian regime and considered a “terrorist” group by the United States, the European Union, and Turkey. At the risk of deepening an Arab Sunni backlash that has fanned radicalization, Washington is set ever more on the prospect of the PYD retaking mostly Arab territory captured by the Islamic State. In line with German reluctance to arm warring sides, Berlin has refrained from giving military aid to the PYD, which is accused of carrying out war crimes. Still, an international effort to rebuild the cantons tied to breaking the PYD’s monopoly on them could help stabilize the area – even more so if Turkey could be brought on board. The Kurds have scored some of the biggest PYD is not calling for outright secession. Its territorial gains in Syria since the outbreak declaration of self-rule and accompanying of revolt against Assad family rule in 2011. “social contract” mix Marxist jargon and a Cooperation with the Assad regime and vague form of popular democracy. The docu- backing from the United States against the ments also emphasize rights for women so-called Islamic State have strengthened and minorities. -

Security Council Distr.: General 30 August 2016 English Original: Arabic

United Nations S/2016/731 Security Council Distr.: General 30 August 2016 English Original: Arabic Identical letters dated 22 August 2016 from the Permanent Representative of the Syrian Arab Republic to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General and the President of the Security Council On instructions from my Government, I should like to convey the position of the Government of the Syrian Arab Republic regarding the thirtieth report of the Secretary-General on the implementation of Security Council resolutions 2139 (2014), 2165 (2014), 2191 (2014) and 2258 (2015) (S/2016/714). The Government of the Syrian Arab Republic reaffirms the positions it has previously communicated in its identical letters to the Secretary-General and the President of the Security Council responding to the reports of the Secretary-General on the implementation of Security Council resolutions 2139 (2014), 2165 (2014), 2191 (2014) and 2258 (2015). The Syrian Government concludes that the present report, like its predecessors, falls fundamentally short of its presumed goal, which is the improvement of humanitarian conditions in Syria, and that the Secretariat is using it to mislead world opinion about the true reasons why humanitarian conditions are deteriorating for Syrians. In addition, the report is being used to level accusations and disparage the massive efforts being made by the Syrian Government aimed at combating terrorism in Syria, restoring security and stability to all Syrian cities and regions so that displaced persons and migrants can return to their homes and lives, and improving the humanitarian situation for Syrians in general. In the present report, as in its predecessors, the Secretariat has displayed a suspicious congruence with the positions and policies of certain influential Security Council members that have adopted positions hostile to the Syrian Government throughout the events that Syria has been experiencing for years.