In the Name of Security Human Rights Violations Under Iran’S National Security Laws

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Being Lesbian in Iran

Human Rights Report Being Lesbian in Iran Human Rights Report: Being Lesbian in Iran 1 About OutRight Every day around the world, LGBTIQ people’s human rights and dignity are abused in ways that shock the conscience. The stories of their struggles and their resilience are astounding, yet remain unknown—or willfully ignored—by those with the power to make change. OutRight Action International, founded in 1990 as the International Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission, works alongside LGBTIQ people in the Global South, with offices in six countries, to help identify community-focused solutions to promote policy for lasting change. We vigilantly monitor and document human rights abuses to spur action when they occur. We train partners to expose abuses and advocate for themselves. Headquartered in New York City, OutRight is the only global LGBTIQ-specific organization with a permanent presence at the United Nations in New York that advocates for human rights progress for LGBTIQ people. [email protected] https://www.facebook.com/outrightintl http://twitter.com/outrightintl http://www.youtube.com/lgbthumanrights http://OutRightInternational.org/iran OutRight Action International 80 Maiden Lane, Suite 1505, New York, NY 10038 U.S.A. P: +1 (212) 430.6054 • F: +1 (212) 430.6060 This work may be reproduced and redistributed, in whole or in part, without alteration and without prior written permission, solely for nonprofit administrative or educational purposes provided all copies contain the following statement: © 2016 OutRight Action International. This work is reproduced and distributed with the permission of OutRight Action International. No other use is permitted without the express prior written permission of OutRight Action International. -

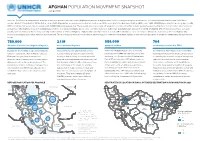

IRN Population Movement Snapshot June 2021

AFGHAN POPULATION MOVEMENT SNAPSHOT June 2021 Since the 1979 Soviet invasion and the subsequent waves of violence that have rocked Afghanistan, millions of Afghans have fled the country, seeking safety elsewhere. The Islamic Republic of Iran boasts 5,894 km of borders. Most of it, including the 921 km that are shared with Afghanistan, are porous and located in remote areas. While according to the Government of Iran (GIRI), some 1,400-2,500 Afghans arrive in Iran every day, recently GIRI has indicated increased daily movements with 4,000-5,000 arriving every day. These people aren’t necesserily all refugees, it is a mixed flow that includes people being pushed by the lack of economic opportunities as well as those who might be in need of international protection. The number fluctuates due to socio-economic challenges both in Iran and Afghanistan and also the COVID-19 situation. UNHCR Iran does not have access to border points and thus is unable to independently monitor arrivals or returns of Afghans. Afghans who currently reside in Iran have dierent statuses: some are refugees (Amayesh card holders), other are Afghans who posses a national passport, while other are undocumented. These populations move across borders in various ways. it is understood that many Afghans in Iran who have passports or are undocumented may have protection needs. 780,000 2.1 M 586,000 704 Amayesh Card Holders (Afghan refugees1) undocumented Afghans passport holders voluntarily repatriated in 2021 In 2001, the Government of Iran issues Amayesh Undocumented is an umbrella term used to There are 275,000 Afghans who hold family Covid-19 had a clear impact on the low VolRep cards to regularize the stay of Afghan refugees. -

Afghans in Iran: Migration Patterns and Aspirations No

TURUN YLIOPISTON MAANTIETEEN JA GEOLOGIAN LAITOKSEN JULKAISUJA PUBLICATIONS OF THE DEPARTMENT OF GEOGRAPHY AND GEOLOGY OF UNIVERSITY OF TURKU MAANTIETEEN JA GEOLOGIAN LAITOS DEPARTMENT OF GEOGRAPHY AND GEOLOGY Afghans in Iran: Migration Patterns and Aspirations Patterns Migration in Iran: Afghans No. 14 TURUN YLIOPISTON MAANTIETEEN JA GEOLOGIAN LAITOKSEN JULKAISUJA PUBLICATIONS FROM THE DEPARTMENT OF GEOGRAPHY AND GEOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF TURKU No. 1. Jukka Käyhkö and Tim Horstkotte (Eds.): Reindeer husbandry under global change in the tundra region of Northern Fennoscandia. 2017. No. 2. Jukka Käyhkö och Tim Horstkotte (Red.): Den globala förändringens inverkan på rennäringen på norra Fennoskandiens tundra. 2017. No. 3. Jukka Käyhkö ja Tim Horstkotte (doaimm.): Boazodoallu globála rievdadusaid siste Davvi-Fennoskandia duottarguovlluin. 2017. AFGHANS IN IRAN: No. 4. Jukka Käyhkö ja Tim Horstkotte (Toim.): Globaalimuutoksen vaikutus porotalouteen Pohjois-Fennoskandian tundra-alueilla. 2017. MIGRATION PATTERNS No. 5. Jussi S. Jauhiainen (Toim.): Turvapaikka Suomesta? Vuoden 2015 turvapaikanhakijat ja turvapaikkaprosessit Suomessa. 2017. AND ASPIRATIONS No. 6. Jussi S. Jauhiainen: Asylum seekers in Lesvos, Greece, 2016-2017. 2017 No. 7. Jussi S. Jauhiainen: Asylum seekers and irregular migrants in Lampedusa, Italy, 2017. 2017 Nro 172 No. 8. Jussi S. Jauhiainen, Katri Gadd & Justus Jokela: Paperittomat Suomessa 2017. 2018. Salavati Sarcheshmeh & Bahram Eyvazlu Jussi S. Jauhiainen, Davood No. 9. Jussi S. Jauhiainen & Davood Eyvazlu: Urbanization, Refugees and Irregular Migrants in Iran, 2017. 2018. No. 10. Jussi S. Jauhiainen & Ekaterina Vorobeva: Migrants, Asylum Seekers and Refugees in Jordan, 2017. 2018. (Eds.) No. 11. Jussi S. Jauhiainen: Refugees and Migrants in Turkey, 2018. 2018. TURKU 2008 ΕήΟΎϬϣΕϼϳΎϤΗϭΎϫϮ̴ϟϥήϳέΩ̶ϧΎΘδϧΎϐϓϥήΟΎϬϣ ISBN No. -

An International Armed Conflict of Low Intensity

THE WAR REPORT THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA AND THE ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF IRAN: AN INTERNATIONAL ARMED CONFLICT OF LOW INTENSITY Aeria view of the Persian Gulf, © NASA DECEMBER 2019 I MILOŠ HRNJAZ THE GENEVA ACADEMY A JOINT CENTER OF Iranian Prime Minister, Mohammed Mosaddeq, pushed CLASSIFICATION OF THE CONFLICT for nationalization of the oil fields and the Shah signed The United States of America and the Islamic Republic of this decision. The response of the British was harsh as they Iran were engaged in an international armed conflict (IAC) saw oil from Iran as a strategic interest. Both Iranians and in June 2019 by virtue of Iran’s shooting down a US military the British expected the support of the US. The Americans drone and the alleged counter cyber-attack by the US. pushed Britain to cancel plans for a military invasion, so the British decided to look for alternative ways to overthrow Mosaddeq. The new US administration wasn’t impressed HISTORY OF THE CONFLICT with Mosaddeq either (especially his flirting with the USSR and the communist Tudeh Party of Iran), so it decided to BACKGROUND actively participate in his overthrow and arrest. This was It has been more than 160 years since the first Treaty perceived by Iranians as the ultimate betrayal by America of Friendship and Commerce was signed between Iran and the event played an important role in the development and the US, exactly 140 years since the first US warship of Iranian political identity and anti-Americanism since entered the Persian Gulf and almost 140 years since Iran then.5 Mosadeqq became the brave figure who represented (Persia) and the US established diplomatic relations.1 Since the fight for independent Iran, free from the influence of then, their relationship has oscillated between cooperation the West. -

IRAN EXECUTIVE SUMMARY the Islamic Republic of Iran

IRAN EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Islamic Republic of Iran is a constitutional, theocratic republic in which Shia Muslim clergy and political leaders vetted by the clergy dominate the key power structures. Government legitimacy is based on the twin pillars of popular sovereignty--albeit restricted--and the rule of the supreme leader of the Islamic Revolution. The current supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, was chosen by a directly elected body of religious leaders, the Assembly of Experts, in 1989. Khamenei’s writ dominates the legislative, executive, and judicial branches of government. He directly controls the armed forces and indirectly controls internal security forces, the judiciary, and other key institutions. The legislative branch is the popularly elected 290-seat Islamic Consultative Assembly, or Majlis. The unelected 12-member Guardian Council reviews all legislation the Majlis passes to ensure adherence to Islamic and constitutional principles; it also screens presidential and Majlis candidates for eligibility. Mahmoud Ahmadinejad was reelected president in June 2009 in a multiparty election that was generally considered neither free nor fair. There were numerous instances in which elements of the security forces acted independently of civilian control. Demonstrations by opposition groups, university students, and others increased during the first few months of the year, inspired in part by events of the Arab Spring. In February hundreds of protesters throughout the country staged rallies to show solidarity with protesters in Tunisia and Egypt. The government responded harshly to protesters and critics, arresting, torturing, and prosecuting them for their dissent. As part of its crackdown, the government increased its oppression of media and the arts, arresting and imprisoning dozens of journalists, bloggers, poets, actors, filmmakers, and artists throughout the year. -

Blood-Soaked Secrets Why Iran’S 1988 Prison Massacres Are Ongoing Crimes Against Humanity

BLOOD-SOAKED SECRETS WHY IRAN’S 1988 PRISON MASSACRES ARE ONGOING CRIMES AGAINST HUMANITY Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2017 Cover photo: Collage of some of the victims of the mass prisoner killings of 1988 in Iran. Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons © Amnesty International (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2017 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: MDE 13/9421/2018 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS GLOSSARY 7 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 8 METHODOLOGY 18 2.1 FRAMEWORK AND SCOPE 18 2.2 RESEARCH METHODS 18 2.2.1 TESTIMONIES 20 2.2.2 DOCUMENTARY EVIDENCE 22 2.2.3 AUDIOVISUAL EVIDENCE 23 2.2.4 COMMUNICATION WITH IRANIAN AUTHORITIES 24 2.3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 25 BACKGROUND 26 3.1 PRE-REVOLUTION REPRESSION 26 3.2 POST-REVOLUTION REPRESSION 27 3.3 IRAN-IRAQ WAR 33 3.4 POLITICAL OPPOSITION GROUPS 33 3.4.1 PEOPLE’S MOJAHEDIN ORGANIZATION OF IRAN 33 3.4.2 FADAIYAN 34 3.4.3 TUDEH PARTY 35 3.4.4 KURDISH DEMOCRATIC PARTY OF IRAN 35 3.4.5 KOMALA 35 3.4.6 OTHER GROUPS 36 4. -

Iran: Ethnic and Religious Minorities

Order Code RL34021 Iran: Ethnic and Religious Minorities Updated November 25, 2008 Hussein D. Hassan Information Research Specialist Knowledge Services Group Iran: Ethnic and Religious Minorities Summary Iran is home to approximately 70.5 million people who are ethnically, religiously, and linguistically diverse. The central authority is dominated by Persians who constitute 51% of Iran’s population. Iranians speak diverse Indo-Iranian, Semitic, Armenian, and Turkic languages. The state religion is Shia, Islam. After installation by Ayatollah Khomeini of an Islamic regime in February 1979, treatment of ethnic and religious minorities grew worse. By summer of 1979, initial violent conflicts erupted between the central authority and members of several tribal, regional, and ethnic minority groups. This initial conflict dashed the hope and expectation of these minorities who were hoping for greater cultural autonomy under the newly created Islamic State. The U.S. State Department’s 2008 Annual Report on International Religious Freedom, released September 19, 2008, cited Iran for widespread serious abuses, including unjust executions, politically motivated abductions by security forces, torture, arbitrary arrest and detention, and arrests of women’s rights activists. According to the State Department’s 2007 Country Report on Human Rights (released on March 11, 2008), Iran’s poor human rights record worsened, and it continued to commit numerous, serious abuses. The government placed severe restrictions on freedom of religion. The report also cited violence and legal and societal discrimination against women, ethnic and religious minorities. Incitement to anti-Semitism also remained a problem. Members of the country’s non-Muslim religious minorities, particularly Baha’is, reported imprisonment, harassment, and intimidation based on their religious beliefs. -

The Coming Iran Nuclear Talks Openings and Obstacles

The Coming Iran Nuclear Talks Openings and Obstacles DENNIS ROSS January 2021 he Middle East will not be a priority in the Biden administration’s approach to foreign policy. But the T Iranian nuclear program will require a response.* With the Iranian parliament having adopted legislation mandating uranium enrichment to 20 percent and suspension of International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) inspections if sanctions are not lifted by February 2020 in response to the targeted killing of Iranian scientist Mohsen Fakhrizadeh— and with Iran now having accumulated twelve times the low-enriched uranium permitted under the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action—the administration will have to deal with the Iranian challenge.1 To be sure, the nuclear program and its potential to make Iran a nuclear weapons state are not the only challenges the Islamic Republic poses: the regime’s ballistic missile program and destabilizing and aggressive behavior in the region threaten conflicts that can escalate both vertically and horizontally. But it is the nuclear program that is most pressing. *The author would like to thank a number of his Washington Institute colleagues—Katherine Bauer, Patrick Clawson, Michael Eisenstadt, Barbara Leaf, Matthew Levitt, David Makovsky, David Pollock, Robert Satloff, and Michael Singh—for the helpful comments they provided as he prepared this paper. He also wants to give special thanks to several people outside the Institute—Robert Einhorn, Richard Nephew, David Petraeus, Norman Roule, and Karim Sadjadpour—for the thoughtful comments -

1 June 8, 2020 to Members of The

June 8, 2020 To Members of the United Nations Human Rights Council Re: Request for the Convening of a Special Session on the Escalating Situation of Police Violence and Repression of Protests in the United States Excellencies, The undersigned family members of victims of police killings and civil society organizations from around the world, call on member states of the UN Human Rights Council to urgently convene a Special Session on the situation of human rights in the United States in order to respond to the unfolding grave human rights crisis borne out of the repression of nationwide protests. The recent protests erupted on May 26 in response to the police murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis, Minnesota, which was only one of a recent string of unlawful killings of unarmed Black people by police and armed white vigilantes. We are deeply concerned about the escalation in violent police responses to largely peaceful protests in the United States, which included the use of rubber bullets, tear gas, pepper spray and in some cases live ammunition, in violation of international standards on the use of force and management of assemblies including recent U.N. Guidance on Less Lethal Weapons. Additionally, we are greatly concerned that rather than using his position to serve as a force for calm and unity, President Trump has chosen to weaponize the tensions through his rhetoric, evidenced by his promise to seize authority from Governors who fail to take the most extreme tactics against protestors and to deploy federal armed forces against protestors (an action which would be of questionable legality). -

The Iranian Revolution in 1979

Demonstrations of the Iranian People’s Mujahideens (Warriors) during the Iranian Revolution in 1979. Dr. Ali Shariati, an Iranian leftist on the left. Ayatollah Khomeini on the right. The Iranian Revolution Gelvin, ch. 17 & 18 & other sources, notes by Denis Bašić The Pahlavi Dynasty • could hardly be called a “dynasty,” for it had only two rulers - Reza Shah Pahlavi (ruled 1926-1941) and his son Muhammad Reza Shah Pahlavi (ruled 1941-1979). • The son came to power after his father was deposed by the Allies (the Russian and British forces) due to his alliance with the Nazi Germany. • The Allies reestablished the majlis and allowed the organization of trade unions and political parties in order to limit the power of the new shah and to prevent him from following his father’s independence course. • Much to the chagrin of the British and Americans, the most popular party proved to be Tudeh - the communist party with more than 100,000 members. • The second Shah’s power was further eroded when in 1951 Muhammad Mossadegh was elected the prime minister on a platform that advocated nationalizing the oil industry and restricting the shah’s power. • Iranian Prime Minister 1951–3. A prominent parliamentarian. He was twice Muhammad appointed to that office by Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the Shah of Iran, after a Mossadegh positive vote of inclination by the 1882-1967 parliament. Mossadegh was a nationalist and passionately opposed foreign intervention in Iran. He was also the architect of the nationalization of the Iranian oil industry, which had been under British control through the Anglo- Iranian Oil Company (AIOC), today known as British Petroleum (BP). -

Next Steps in Syria

Next Steps in Syria BY JUDITH S. YAPHE early three years since the start of the Syrian civil war, no clear winner is in sight. Assassinations and defections of civilian and military loyalists close to President Bashar Nal-Assad, rebel success in parts of Aleppo and other key towns, and the spread of vio- lence to Damascus itself suggest that the regime is losing ground to its opposition. The tenacity of government forces in retaking territory lost to rebel factions, such as the key town of Qusayr, and attacks on Turkish and Lebanese military targets indicate, however, that the regime can win because of superior military equipment, especially airpower and missiles, and help from Iran and Hizballah. No one is prepared to confidently predict when the regime will collapse or if its oppo- nents can win. At this point several assessments seem clear: ■■ The Syrian opposition will continue to reject any compromise that keeps Assad in power and imposes a transitional government that includes loyalists of the current Baathist regime. While a compromise could ensure continuity of government and a degree of institutional sta- bility, it will almost certainly lead to protracted unrest and reprisals, especially if regime appoin- tees and loyalists remain in control of the police and internal security services. ■■ How Assad goes matters. He could be removed by coup, assassination, or an arranged exile. Whether by external or internal means, building a compromise transitional government after Assad will be complicated by three factors: disarray in the Syrian opposition, disagreement among United Nations (UN) Security Council members, and an intransigent sitting govern- ment. -

PDF Fileiranian Migrations to Dubai: Constraints and Autonomy of A

Iranian Migrations to Dubai: Constraints and Autonomy of a Segmented Diaspora Amin Moghadam Working Paper No. 2021/3 January 2021 The Working Papers Series is produced jointly by the Ryerson Centre for Immigration and Settlement (RCIS) and the CERC in Migration and Integration www.ryerson.ca/rcis www.ryerson.ca/cerc-migration Working Paper No. 2021/3 Iranian Migrations to Dubai: Constraints and Autonomy of a Segmented Diaspora Amin Moghadam Ryerson University Series Editors: Anna Triandafyllidou and Usha George The Working Papers Series is produced jointly by the Ryerson Centre for Immigration and Settlement (RCIS) and the CERC in Migration and Integration at Ryerson University. Working Papers present scholarly research of all disciplines on issues related to immigration and settlement. The purpose is to stimulate discussion and collect feedback. The views expressed by the author(s) do not necessarily reflect those of the RCIS or the CERC. For further information, visit www.ryerson.ca/rcis and www.ryerson.ca/cerc-migration. ISSN: 1929-9915 Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 2.5 Canada License A. Moghadam Abstract In this paper I examine the way modalities of mobility and settlement contribute to the socio- economic stratification of the Iranian community in Dubai, while simultaneously reflecting its segmented nature, complex internal dynamics, and relationship to the environment in which it is formed. I will analyze Iranian migrants’ representations and their cultural initiatives to help elucidate the socio-economic hierarchies that result from differentiated access to distinct social spaces as well as the agency that migrants have over these hierarchies. In doing so, I examine how social categories constructed in the contexts of departure and arrival contribute to shaping migratory trajectories.