NOAA Technical Report NMFS SSRF- 740

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

§4-71-6.5 LIST of CONDITIONALLY APPROVED ANIMALS November

§4-71-6.5 LIST OF CONDITIONALLY APPROVED ANIMALS November 28, 2006 SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME INVERTEBRATES PHYLUM Annelida CLASS Oligochaeta ORDER Plesiopora FAMILY Tubificidae Tubifex (all species in genus) worm, tubifex PHYLUM Arthropoda CLASS Crustacea ORDER Anostraca FAMILY Artemiidae Artemia (all species in genus) shrimp, brine ORDER Cladocera FAMILY Daphnidae Daphnia (all species in genus) flea, water ORDER Decapoda FAMILY Atelecyclidae Erimacrus isenbeckii crab, horsehair FAMILY Cancridae Cancer antennarius crab, California rock Cancer anthonyi crab, yellowstone Cancer borealis crab, Jonah Cancer magister crab, dungeness Cancer productus crab, rock (red) FAMILY Geryonidae Geryon affinis crab, golden FAMILY Lithodidae Paralithodes camtschatica crab, Alaskan king FAMILY Majidae Chionocetes bairdi crab, snow Chionocetes opilio crab, snow 1 CONDITIONAL ANIMAL LIST §4-71-6.5 SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME Chionocetes tanneri crab, snow FAMILY Nephropidae Homarus (all species in genus) lobster, true FAMILY Palaemonidae Macrobrachium lar shrimp, freshwater Macrobrachium rosenbergi prawn, giant long-legged FAMILY Palinuridae Jasus (all species in genus) crayfish, saltwater; lobster Panulirus argus lobster, Atlantic spiny Panulirus longipes femoristriga crayfish, saltwater Panulirus pencillatus lobster, spiny FAMILY Portunidae Callinectes sapidus crab, blue Scylla serrata crab, Samoan; serrate, swimming FAMILY Raninidae Ranina ranina crab, spanner; red frog, Hawaiian CLASS Insecta ORDER Coleoptera FAMILY Tenebrionidae Tenebrio molitor mealworm, -

A Concept for Assuring the Quality of Seafoods to Consumers

MFR PAPER 1276 Table I.-The approximate shelf life of cod fillets (Ronalvalll et aI., 1973). Temperalure Approximate OF 0C shelf file (days) 32 0 14 A Concept for Assuring the Quality of 34 1.11 11 37 2.78 8 39 3.89 7 Seafoods to Consumers 41 5.00 6 44 6.67 5 49 9.44 4 56 13.30 3 L. J. RONSIVALLI, C. GORGA, J. D. KAYLOR, and J. H. CARVER at 31°_33°F (-0.56°-0.56°C) is about 2 weeks from the time they are har vested. (The shelf life of a product, in ABSTRACT - For more than a decade numerous surveys of the quality of this case, ends when it becomes unac seafoods at retail counters have resulted in consistent adverse reports, and it has ceptable as a food; that is, the total time been concluded that the unreliability of the quality of seafoods is the major reason it takes for the product to change from why their per capita consumption is so much lower than it is for beef, pork, or Grade A to Grade B to Grade C and then poultry. A concept for insuring the Grade A quality ofseafoods was developed and to the point just before it becomes unac tested in an attempt to demonstrate that the consumption offresh fish will increase ceptable.)' It has been established that when their quality and image are improved. This paper describes the concept, its the shelf life of fresh seafoods is af implementation under federal coordination, and its successful implementation by fected mainly by the temperature at industry which has grown from a pilot operation involving five retail stores and which they are held (Table 1). -

Foreign Fishery Trade

August 1946 COMMERCIAL FISHERIES REVIEW 31 FOREIGN FISHERY TRADE Imports and Exports GROUNDFISH IMPORTS: From January 1 through J~e 29,1946, there were 24,676,000 pounds of fresh and frozen groundfish imported into the United States under the special tariff classification "Fish, fresh or frozen fillets, steaks, etc., of cod, haddock, hake, cusk, pollock, and rosefish." Approximately 19,615,000 pounds were received during the corresponding period in 1945, according to a report re ceived from the Bureau of Customs of the Treasury Department. The reduced tariff quota for the year is 20,380,724 pounds. June 2-29, Apr. 'LJ- June Jan. 1- Jan. 1- Commodity 1946 June 1.1946 19A5 June _29_ l~6 June J.o 1'3A5. Fish, fresh or frozen fillets, steaks, etc•• I of cod, haddock, hake, 4,330,976 3,983,146 3,176,093 24,675,749 19.615,133 cusk, pollock, and rosefish Canada COLD~STORAGE: Canadian freezings of fresh fishery products in May totaled 14,422,000 pounds. HeaViest freezings were of whole cod, cod fil~ets, and halibut, according to a preliminary report of the Department of Trade and Commerce of the DOminion Bureau of Statistics. Holdings totaled 22,309,000 pounds on June 1, compared with 15,537,000 pounds on May 1 and 17,489,000 pounds on June 1, 1945. Ecuador FISHING REGULATION: A report trom the American Embassy at ~uito, Ecuador, received by the State Department on July 1, 1946, states that the President of Ecuador, on December 27, 1945, signed Exeoutive Decree No. -

CHAPTER 3 FISH and CRUSTACEANS, MOLLUSCS and OTHER AQUATIC INVERTEBRATES I 3-L Note

)&f1y3X CHAPTER 3 FISH AND CRUSTACEANS, MOLLUSCS AND OTHER AQUATIC INVERTEBRATES I 3-l Note 1. This chapter does not cover: (a) Marine mammals (heading 0106) or meat thereof (heading 0208 or 0210); (b) Fish (including livers and roes thereof) or crustaceans, molluscs or other aquatic invertebrates, dead and unfit or unsuitable for human consumption by reason of either their species or their condition (chapter 5); flours, meals or pellets of fish or of crustaceans, molluscs or other aquatic invertebrates, unfit for human consumption (heading 2301); or (c) Caviar or caviar substitutes prepared from fish eggs (heading 1604). 2. In this chapter the term "pellets" means products which have been agglomerated either directly by compression or by the addition of a small quantity of binder. Additional U.S. Note 1. Certain fish, crustaceans, molluscs and other aquatic invertebrates are provided for in chapter 98. )&f2y3X I 3-2 0301 Live fish: 0301.10.00 00 Ornamental fish............................... X....... Free Free Other live fish: 0301.91.00 00 Trout (Salmo trutta, Salmo gairdneri, Salmo clarki, Salmo aguabonita, Salmo gilae)................................... X....... Free Free 0301.92.00 00 Eels (Anguilla spp.)..................... kg...... Free Free 0301.93.00 00 Carp..................................... X....... Free Free 0301.99.00 00 Other.................................... X....... Free Free 0302 Fish, fresh or chilled, excluding fish fillets and other fish meat of heading 0304: Salmonidae, excluding livers and roes: 0302.11.00 Trout (Salmo trutta, Salmo gairdneri, Salmo clarki, Salmo aguabonita, Salmo gilae)................................... ........ Free 2.2¢/kg 10 Rainbow trout (Salmo gairnderi), farmed.............................. kg 90 Other............................... kg 0302.12.00 Pacific salmon (Oncorhynchus spp.), Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) and Danube salmon (Hucho hucho)............. -

Portadas 21 (1)

© Sociedad Española de Malacología Iberus , 21 (1): 115-127, 2003 Four new Euthria (Mollusca, Buccinidae) from the Cape Verde archipelago, with comments on the validity of the genus Cuatro nuevas Euthria (Mollusca, Buccinidae) del archipiélago de Cabo Verde con comentarios sobre la validez del género Emilio ROLÁN *, António MONTEIRO ** and Koen FRAUSSEN *** Recibido el 2-XII-2002. Aceptado el 22-I-2003 ABSTRACT Four species, collected in the Cape Verde Islands, are described as new and assigned to the genus Euthria M. E. Gray, 1830. The new species are compared with other taxa from the Mediterranean Sea and the Cape Verde Archipelago. The genera Euthria , and Buccin - ulum are compared and the significance of the differences between them is discussed, leading to the conclusion that both genera are valid and should be kept separated. RESUMEN Se describen cuatro especies nuevas del género Euthria M. E. Gray, 1830 recogidas en aguas circalitorales del archipiélago de Cabo Verde. Las nuevas especies son compara - das con otros taxones congenéricos existentes en el Mediterráneo y en el propio archip - iélago. Recientemente, el género Euthria, únicamente conocido del Atlántico oriental, ha sido sinonimizado con Buccinulum , que posee especies en el Indo-Pacífico, por lo que se comparan ambos géneros y se discute el valor de las diferencias entre ellos, considerando finalmente que ambos son válidos, y deben mantenerse separados. KEY WORDS: Euthria , Buccinulum , Cape Verde Archipelago, new taxa. PALABRAS CLAVE : Euthria , Buccinulum , Archipiélago de Cabo Verde, nuevos táxones. INTRODUCTION During the last few years, the genus them separate, as commented upon in Euthria Gray, 1850 has frequently been “Remarks” of this paper. -

Turbinellidae

WMSDB - Worldwide Mollusc Species Data Base Family: TURBINELLIDAE Author: Claudio Galli - [email protected] (updated 07/set/2015) Class: GASTROPODA --- Clade: CAENOGASTROPODA-HYPSOGASTROPODA-NEOGASTROPODA-MURICOIDEA ------ Family: TURBINELLIDAE Swainson, 1835 (Sea) - Alphabetic order - when first name is in bold the species has images Taxa=276, Genus=12, Subgenus=4, Species=91, Subspecies=13, Synonyms=155, Images=87 aapta , Coluzea aapta M.G. Harasewych, 1986 acuminata, Turbinella acuminata L.C. Kiener, 1840 - syn of: Latirus acuminatus (L.C. Kiener, 1840) aequilonius, Fulgurofusus aequilonius A.V. Sysoev, 2000 agrestis, Turbinella agrestis H.E. Anton, 1838 - syn of: Nicema subrostrata (J.E. Gray, 1839) aldridgei , Vasum aldridgei G.W. Nowell-Usticke, 1969 - syn of: Attiliosa aldridgei (G.W. Nowell-Usticke, 1969) altocanalis , Coluzea altocanalis R.K. Dell, 1956 amaliae , Turbinella amaliae H.C. Küster & W. Kobelt, 1874 - syn of: Hemipolygona amaliae (H.C. Küster & W. Kobelt, 1874) angularis , Coluzea angularis (K.H. Barnard, 1959) angularis , Turbinella angularis L.A. Reeve, 1847 - syn of: Leucozonia nassa (J.F. Gmelin, 1791) angularis riiseana , Turbinella angularis riiseana H.C. Küster & W. Kobelt, 1874 - syn of: Leucozonia nassa (J.F. Gmelin, 1791) angulata , Turbinella angulata (J. Lightfoot, 1786) annulata, Syrinx annulata P.F. Röding, 1798 - syn of: Pustulatirus annulatus (P.F. Röding, 1798) aptos , Columbarium aptos M.G. Harasewych, 1986 - syn of: Coluzea aapta M.G. Harasewych, 1986 ardeola , Vasum ardeola A. Valenciennes, 1832 - syn of: Vasum caestus (W.J. Broderip, 1833) armatum , Vasum armatum (W.J. Broderip, 1833) armigera , Tudivasum armigera A. Adams, 1855 - syn of: Tudivasum armigerum (A. Adams, 1856) armigera , Turbinella armigera J.B.P.A. -

Keyspan Energy - Ravenswood Cogeneration Facility Article X Application

KeySpan Energy - Ravenswood Cogeneration Facility Article X Application 8.1 Introduction A thorough understanding of several key elements is essential in anticipating the potential effects of a proposed power plant. Arguably, the most important of these factors is the pattern and magnitude of the cooling water flow because cooling water withdrawal, total flow, and intake velocity play a fundamental role in determining the number of organisms lost through entrainment and impingement. Additionally, cooling water discharge-coupled with the physical characteristics of the discharge structure-determines the spatial orientation of the thermal plume. This orientation, in turn, can affect aquatic species. It should be noted that the intake volume is not necessarily the same as the discharge volume. For example, the cooling water discharge from a wet closed-cycle cooling system is the intake volume less the amount lost to atmospheric evaporation. A second set of factors critical to the determination of potential impact on aquatic organisms is the load carried by the generating unit and the characteristics of the pumping system. Generally, increased load requires increased cooling water flow. This increase, however, may not necessarily translate on a one-to-one basis because many generating units employ fixed speed pumps that are on whenever the unit is generating power, regardless of load. A third set of considerations is the availability of power generated by other competing units. Under a deregulated market, a surplus of available power will limit the demand from uneconomical producers. This, in turn, limits intake flow and heat discharge from these units. Finally, all of these factors must be estimated to reflect future conditions, including demand for power, because the analysis is intended to forecast future impacts, rather than reflect past performance. -

Rumahlatu D., Leiwakabessy F., 2017 Biodiversity of Gastropoda in the Coastal Waters of Ambon Island, Indonesia

Biodiversity of gastropoda in the coastal waters of Ambon Island, Indonesia Dominggus Rumahlatu, Fredy Leiwakabessy Biology Education Study Program, Faculty of Teacher Training and Education Science, Pattimura University, Ambon, Indonesia. Corresponding author: D. Rumahlatu, [email protected] Abstract. Gastropods belonging to the mollusk phylum are widespread in various ecosystems. Ecologically, the spread of gastropoda is influenced by environmental factors, such as temperature, salinity, pH and dissolved oxygen. This research was conducted to determine the correlation between the factors of physico-chemical environment and the diversity of gastropoda in coastal water of Ambon Island, Indonesia. This research was conducted at two research stations, namely Station 1 at Ujung Tanjung Latuhalat Beach and Station 2 at coastal water of Waitatiri Passo. The results of a survey revealed that the average temperature on station 1 was 31.14°C while the average temperature of ° station 2 was 29.90 C. The average salinity at Station 1 was 32.02%o whereas the salinity average at Station 2 was 30.31%o. The average pH in station 1 and 2 was 7.03, while the dissolved oxygen at station 1 was 7.68 ppm which was not far different from that in station 2 with the dissolved oxygen of 7.63 ppm. The total number of species found in both research stations was 65 species, with the types of gastropoda were found scattered in 48 genera, 19 families and 7 orders. The most commonly found gastropods were from the genus of Nerita and Conus. 40 species were found in station 1 and 40 species were found in station 2. -

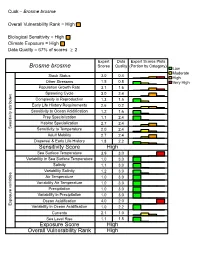

Brosme Brosme

Cusk − Brosme brosme Overall Vulnerability Rank = High Biological Sensitivity = High Climate Exposure = High Data Quality = 67% of scores ≥ 2 Expert Data Expert Scores Plots Scores Quality (Portion by Category) Brosme brosme Low Moderate Stock Status 3.0 0.4 High Other Stressors 1.5 0.8 Very High Population Growth Rate 3.1 1.6 Spawning Cycle 3.0 2.4 Complexity in Reproduction 1.3 1.5 Early Life History Requirements 2.6 0.2 Sensitivity to Ocean Acidification 1.2 1.6 Prey Specialization 1.1 2.4 Habitat Specialization 2.7 2.4 Sensitivity attributes Sensitivity to Temperature 2.0 2.4 Adult Mobility 2.7 2.4 Dispersal & Early Life History 1.8 2.2 Sensitivity Score High Sea Surface Temperature 3.9 3.0 Variability in Sea Surface Temperature 1.0 3.0 Salinity 1.1 3.0 Variability Salinity 1.2 3.0 Air Temperature 1.0 3.0 Variability Air Temperature 1.0 3.0 Precipitation 1.0 3.0 Variability in Precipitation 1.0 3.0 Ocean Acidification 4.0 2.0 Exposure variables Variability in Ocean Acidification 1.0 2.2 Currents 2.1 1.0 Sea Level Rise 1.1 1.5 Exposure Score High Overall Vulnerability Rank High Cusk (Brosme brosme) Overall Climate Vulnerability Rank: High (69% certainty from bootstrap analysis). Climate Exposure: High. Two exposure factors contributed to this score: Ocean Surface Temperature (3.9) and Ocean Acidification (4.0). All life stages of Cusk use marine habitats. Biological Sensitivity: High. Three sensitivity attributes scored above 3.0: Stock Status (3.0), Population Growth Rate (3.1), and Spawning Cycle (3.0). -

The Nautilus

THE NAUTILUS Volume 120, Numberl May 30, 2006 ISSN 0028-1344 A quarterly devoted to malacology. EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Dr. Douglas S. Jones Dr. Angel Valdes Florida Museum of Natural History Department of Malacology Dr. Jose H. Leal University of Florida Natural Histoiy Museum The Bailey-Matthews Shell Museum Gainesville, FL 32611-2035 of Los Angeles County 3075 Sanibel-Captiva Road 900 Exposition Boulevard Sanibel, FL 33957 Dr. Harry G. Lee Los Angeles, CA 90007 MANAGING EDITOR 1801 Barrs Street, Suite 500 Dr. Geerat Vermeij Jacksonville, FL 32204 J. Linda Kramer Department of Geology Shell Museum The Bailey-Matthews Dr. Charles Lydeard University of California at Davis 3075 Sanibel-Captiva Road Biodiversity and Systematics Davis, CA 95616 Sanibel, FL 33957 Department of Biological Sciences Dr. G. Thomas Watters University of Alabama EDITOR EMERITUS Aquatic Ecology Laboratory Tuscaloosa, AL 35487 Dr. M. G. Harasewych 1314 Kinnear Road Department of Invertebrate Zoology Bruce A. Marshall Columbus, OH 43212-1194 National Museum of Museum of New Zealand Dr. John B. Wise Natural History Te Papa Tongarewa Department oi Biology Smithsonian Institution P.O. Box 467 College of Charleston Washington, DC 20560 Wellington, NEW ZEALAND Charleston, SC 29424 CONSULTING EDITORS Dr. James H. McLean SUBSCRIPTION INFORMATION Dr. Riidiger Bieler Department of Malacology Department of Invertebrates Natural History Museum The subscription rate per volume is Field Museum of of Los Angeles County US $43.00 for individuals, US $72.00 Natural History 900 Exposition Boulevard for institutions. Postage outside the Chicago, IL 60605 Los Angeles, CA 90007 United States is an additional US $5.00 for surface and US $15.00 for Dr. -

Cusk (Brosme Brosme)

Cusk (Brosme brosme) Family Gadidae, Cods Common name: cusk Description: Cusk are dark slate to red brown above with yellowish sides and a dirty white underbody. They have an elongated, taper shaped body with a blunt snout and a single barbel on their chin. Their dorsal and anal fins are exceptionally long and they have a rounded tail fin, all of which are bordered with a black stripe that is edged in white. Cusk can grow to a size of about 3 1/2 feet in length and to 30 pounds in weight. Their average size in the waters of the Gulf of Maine, however, is closer to 1 1/2 to 2 1/2 feet in length and 5 to 10 pounds in weight. Where found: offshore Similar Gulf of Maine species: wolffish, eel pout Remarks: Cusk are exclusively bottom dwellers that inhabit moderately deep waters of 60 to 90 feet. They prefer a hard rough substrate made up of rocks or boulders. These fish are solitary in nature and are not particularly abundant. Cusk are excellent table fare, particularly in chowders and stews. Occasionally, anglers will hook onto a cusk while fishing for cod or haddock. Although these fish are considered to be weak and sluggish swimmers, they have a powerful body. Both clams and herring work well as bait when fishing for cusk. Records: MSSAR IGFA AllTackle World Record Fish Illustrations by: Roz Davis Designs, Damariscotta, ME (207) 5632286 With permission, the use of these pictures must state the following: Drawings provided courtesy of the Maine Department of Marine Resources Recreational Fisheries program and the Maine Outdoor Heritage Fund.. -

Gastropoda, Buccinidae), a Reappraisal

Beets, Notes on Buccinulum, a reappraisal, Scripta Geol., 82 (1986) Notes on Buccinulum (Gastropoda, Buccinidae), a reappraisal C. Beets Beets, C. Notes on Buccinulum (Gastropoda, Buccinidae), a reappraisal. — Scripta Geol., 82: 83-100, pis 6-7, Leiden, January 1987 An attempt was made to assemble what is known at present of Buccinulum in the Indo-Western Pacific Region, fossil and Recent, more scope being offered by the discovery of new Miocene fossils from Java and Sumatra, and the recognition of further fossil species from India and Burma. This induced comparisons with, and revisions of some of the fossil and living species occurring in adjacent zoogeographical provinces. The Recent distribution of the subgenus Euthria appears to be much more extensive than when recorded by Wenz (1938-1944), the minimum enlargement encompassing an area stretching from the eastern Indian Ocean to Japan, via the Philippines and Ryukyu Islands. The knowledge of its fossil distribution, in the Indopacific Region long confined to Javanese Eocene, has likewise greatly expanded by discoveries made in Neogene to Quaternary of India, Burma, Indonesia (Sumatra, Java, Madura, and Borneo), the Philippines, New Hebrides, Fiji?, Ryukyu Islands, and Japan. The relevant data were tabulated. New taxa described are: Buccinulum pendopoense and B. sumatrense, both from presumed Preangerian of Sumatra, and B. walleri sedanense from the Rembangian of Java. It is proposed to include Ornopsis, which was described from the Upper Cretaceous of North America, as a subgenus of Buccinulum. It may well be ancestral to Euthria, considering its similarity to certain of the latter's fossil and living species.