Temporal Trends in Cusk Eel Sound Production at a Proposed US Wind Farm Site

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Concept for Assuring the Quality of Seafoods to Consumers

MFR PAPER 1276 Table I.-The approximate shelf life of cod fillets (Ronalvalll et aI., 1973). Temperalure Approximate OF 0C shelf file (days) 32 0 14 A Concept for Assuring the Quality of 34 1.11 11 37 2.78 8 39 3.89 7 Seafoods to Consumers 41 5.00 6 44 6.67 5 49 9.44 4 56 13.30 3 L. J. RONSIVALLI, C. GORGA, J. D. KAYLOR, and J. H. CARVER at 31°_33°F (-0.56°-0.56°C) is about 2 weeks from the time they are har vested. (The shelf life of a product, in ABSTRACT - For more than a decade numerous surveys of the quality of this case, ends when it becomes unac seafoods at retail counters have resulted in consistent adverse reports, and it has ceptable as a food; that is, the total time been concluded that the unreliability of the quality of seafoods is the major reason it takes for the product to change from why their per capita consumption is so much lower than it is for beef, pork, or Grade A to Grade B to Grade C and then poultry. A concept for insuring the Grade A quality ofseafoods was developed and to the point just before it becomes unac tested in an attempt to demonstrate that the consumption offresh fish will increase ceptable.)' It has been established that when their quality and image are improved. This paper describes the concept, its the shelf life of fresh seafoods is af implementation under federal coordination, and its successful implementation by fected mainly by the temperature at industry which has grown from a pilot operation involving five retail stores and which they are held (Table 1). -

Foreign Fishery Trade

August 1946 COMMERCIAL FISHERIES REVIEW 31 FOREIGN FISHERY TRADE Imports and Exports GROUNDFISH IMPORTS: From January 1 through J~e 29,1946, there were 24,676,000 pounds of fresh and frozen groundfish imported into the United States under the special tariff classification "Fish, fresh or frozen fillets, steaks, etc., of cod, haddock, hake, cusk, pollock, and rosefish." Approximately 19,615,000 pounds were received during the corresponding period in 1945, according to a report re ceived from the Bureau of Customs of the Treasury Department. The reduced tariff quota for the year is 20,380,724 pounds. June 2-29, Apr. 'LJ- June Jan. 1- Jan. 1- Commodity 1946 June 1.1946 19A5 June _29_ l~6 June J.o 1'3A5. Fish, fresh or frozen fillets, steaks, etc•• I of cod, haddock, hake, 4,330,976 3,983,146 3,176,093 24,675,749 19.615,133 cusk, pollock, and rosefish Canada COLD~STORAGE: Canadian freezings of fresh fishery products in May totaled 14,422,000 pounds. HeaViest freezings were of whole cod, cod fil~ets, and halibut, according to a preliminary report of the Department of Trade and Commerce of the DOminion Bureau of Statistics. Holdings totaled 22,309,000 pounds on June 1, compared with 15,537,000 pounds on May 1 and 17,489,000 pounds on June 1, 1945. Ecuador FISHING REGULATION: A report trom the American Embassy at ~uito, Ecuador, received by the State Department on July 1, 1946, states that the President of Ecuador, on December 27, 1945, signed Exeoutive Decree No. -

CHAPTER 3 FISH and CRUSTACEANS, MOLLUSCS and OTHER AQUATIC INVERTEBRATES I 3-L Note

)&f1y3X CHAPTER 3 FISH AND CRUSTACEANS, MOLLUSCS AND OTHER AQUATIC INVERTEBRATES I 3-l Note 1. This chapter does not cover: (a) Marine mammals (heading 0106) or meat thereof (heading 0208 or 0210); (b) Fish (including livers and roes thereof) or crustaceans, molluscs or other aquatic invertebrates, dead and unfit or unsuitable for human consumption by reason of either their species or their condition (chapter 5); flours, meals or pellets of fish or of crustaceans, molluscs or other aquatic invertebrates, unfit for human consumption (heading 2301); or (c) Caviar or caviar substitutes prepared from fish eggs (heading 1604). 2. In this chapter the term "pellets" means products which have been agglomerated either directly by compression or by the addition of a small quantity of binder. Additional U.S. Note 1. Certain fish, crustaceans, molluscs and other aquatic invertebrates are provided for in chapter 98. )&f2y3X I 3-2 0301 Live fish: 0301.10.00 00 Ornamental fish............................... X....... Free Free Other live fish: 0301.91.00 00 Trout (Salmo trutta, Salmo gairdneri, Salmo clarki, Salmo aguabonita, Salmo gilae)................................... X....... Free Free 0301.92.00 00 Eels (Anguilla spp.)..................... kg...... Free Free 0301.93.00 00 Carp..................................... X....... Free Free 0301.99.00 00 Other.................................... X....... Free Free 0302 Fish, fresh or chilled, excluding fish fillets and other fish meat of heading 0304: Salmonidae, excluding livers and roes: 0302.11.00 Trout (Salmo trutta, Salmo gairdneri, Salmo clarki, Salmo aguabonita, Salmo gilae)................................... ........ Free 2.2¢/kg 10 Rainbow trout (Salmo gairnderi), farmed.............................. kg 90 Other............................... kg 0302.12.00 Pacific salmon (Oncorhynchus spp.), Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) and Danube salmon (Hucho hucho)............. -

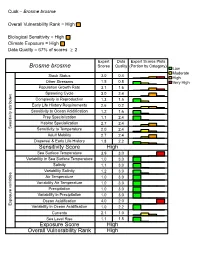

Brosme Brosme

Cusk − Brosme brosme Overall Vulnerability Rank = High Biological Sensitivity = High Climate Exposure = High Data Quality = 67% of scores ≥ 2 Expert Data Expert Scores Plots Scores Quality (Portion by Category) Brosme brosme Low Moderate Stock Status 3.0 0.4 High Other Stressors 1.5 0.8 Very High Population Growth Rate 3.1 1.6 Spawning Cycle 3.0 2.4 Complexity in Reproduction 1.3 1.5 Early Life History Requirements 2.6 0.2 Sensitivity to Ocean Acidification 1.2 1.6 Prey Specialization 1.1 2.4 Habitat Specialization 2.7 2.4 Sensitivity attributes Sensitivity to Temperature 2.0 2.4 Adult Mobility 2.7 2.4 Dispersal & Early Life History 1.8 2.2 Sensitivity Score High Sea Surface Temperature 3.9 3.0 Variability in Sea Surface Temperature 1.0 3.0 Salinity 1.1 3.0 Variability Salinity 1.2 3.0 Air Temperature 1.0 3.0 Variability Air Temperature 1.0 3.0 Precipitation 1.0 3.0 Variability in Precipitation 1.0 3.0 Ocean Acidification 4.0 2.0 Exposure variables Variability in Ocean Acidification 1.0 2.2 Currents 2.1 1.0 Sea Level Rise 1.1 1.5 Exposure Score High Overall Vulnerability Rank High Cusk (Brosme brosme) Overall Climate Vulnerability Rank: High (69% certainty from bootstrap analysis). Climate Exposure: High. Two exposure factors contributed to this score: Ocean Surface Temperature (3.9) and Ocean Acidification (4.0). All life stages of Cusk use marine habitats. Biological Sensitivity: High. Three sensitivity attributes scored above 3.0: Stock Status (3.0), Population Growth Rate (3.1), and Spawning Cycle (3.0). -

Cusk (Brosme Brosme)

Cusk (Brosme brosme) Family Gadidae, Cods Common name: cusk Description: Cusk are dark slate to red brown above with yellowish sides and a dirty white underbody. They have an elongated, taper shaped body with a blunt snout and a single barbel on their chin. Their dorsal and anal fins are exceptionally long and they have a rounded tail fin, all of which are bordered with a black stripe that is edged in white. Cusk can grow to a size of about 3 1/2 feet in length and to 30 pounds in weight. Their average size in the waters of the Gulf of Maine, however, is closer to 1 1/2 to 2 1/2 feet in length and 5 to 10 pounds in weight. Where found: offshore Similar Gulf of Maine species: wolffish, eel pout Remarks: Cusk are exclusively bottom dwellers that inhabit moderately deep waters of 60 to 90 feet. They prefer a hard rough substrate made up of rocks or boulders. These fish are solitary in nature and are not particularly abundant. Cusk are excellent table fare, particularly in chowders and stews. Occasionally, anglers will hook onto a cusk while fishing for cod or haddock. Although these fish are considered to be weak and sluggish swimmers, they have a powerful body. Both clams and herring work well as bait when fishing for cusk. Records: MSSAR IGFA AllTackle World Record Fish Illustrations by: Roz Davis Designs, Damariscotta, ME (207) 5632286 With permission, the use of these pictures must state the following: Drawings provided courtesy of the Maine Department of Marine Resources Recreational Fisheries program and the Maine Outdoor Heritage Fund.. -

Guide to Some Trawl-Caught Marine Fishes from Maine to Cape Hatteras, North Carolina

431 NOAA Technical Report NMFS Circular 431 Guide to Some Trawl-Caught Marine Fishes From Maine to Cape Hatteras, North Carolina Donald D. Flescher March 1980 U.S . DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration National Marine Fisheries Service NOAA TECHNICAL REPORTS National Marine Fisheries Service, Circulars The major responsibiilties III the "attllnol \Iann.' FI,hpnp, ",'rvllP I:-':\HSI ArI' t(, m(,ml"r snd delhI aIJundan(t and j(Pfll(raphlf dlStrihution IIf lisherv r~sources, til unlierslunli snd prelil' I flUCI'.I1t1 ",ns In t hi' 4U n',1\ and d, trJbut H'n (,I Ihe < re rune and til E' labli h leHI lor optImum use of the resour('es, ,\:\IF:-; IS also (harged wllh Ih., d,'v!'lopmenl and ,mT,lementst,,·n "I poil" , I'lf man gllll( nallonal II hlnl( grounds, development and pnfoflempnt 01 dome,t'l Ii,hen," rpgu~AtH·ns, "If\(,1;18nCI' (of f'·rell(n f, h nj( "ft I nl'('(l"l I" ('Ia till "dler ann thE' development and enlorcement "I IllternatillnallJsh.n ul(rf't'menls and pollCl"s .... :\1~" .,1,,· a" I Ihe" hlng Ind •• Ir thr"ul'h rnarhltnj( ef\ ce and e(,lInllmlt anal\", prClgnl'n,. and ""rtgage n, Han' e and \(,,,(,1 (·m trurtll" L,h"d'e It, (" e I anal\le lnd puh he \3f1I1US phases "f the Indust r\ Tht' ,\OAA Technical Hpp"rt '\IF:-. t'Jr(ular "'rJ!" r m',n Ie'" ,eflt th,,' hft heN, n ( le'He ,net'. II. The (,r- 11M publicallons "I general'l1lt'resl Inlennt'ri I" ~J(! (lI"pr\.lIH·O and manag('rr(nl Puhl" tl' In 'Ilat rt"~" .n ('Ill lripnhp dr'~" lechnl(alleHI cerlaln hn an arfd' It research ~T:)ear in 'hi ,tnt· I fllln 01 paper. -

Definitions of FAOSTAT Fish Food Commodities Appendix 2

Definitions of FAOSTAT fish food commodities Appendix 2 Commodity Definitions, coverage, remarks Freshwater and Diadromous, Fresh Fresh raw whole fish including bones, skin, head, etc. The inedible part of the whole fish is 20–50%. Barb, burbot, carps, catfish, dace, freshwater breams, freshwater drum, gabies, giant sea perch=barramundi, gourami, gudgeons, mandarin fish, milkfish, nile perch, paddlefishes, perch, pike, river eels, salmons, shads, sleepers, smelts, snakehead, sturgeons, tenchs, tilapias, trouts and miscellaneous freshwater and diadromous fishes, etc. Freshwater and Diadromous, Frozen Whole Frozen raw gutted whole fish including bones, skin, head, etc. The inedible part of the whole fish is 20–50%. Freshwater and Diadromous, Fillets Fresh raw fillets (all edible). Freshwater and Diadromous, Frozen Fillets Frozen raw fillets (all edible). Freshwater and Diadromous, Cured Salted, dried, smoked whole fish or fillets. The inedible part of the whole fish is 20–50%. Examples are: dried salted sturgeon (balyk), smoked salmon, smoked trout. Freshwater and Diadromous, Canned Headed, gutted or filleted in airtight containers, in brine, oil or other medium (all edible). Examples are: salmon canned in brine, unagi (eel) in vacuum packs. Freshwater and Diadromous, Preparations Fresh or frozen whole fish or fillets then cooked (inedible part is 0–50%). Fish roes (carp, salmon, trout, Examples are: caviar, red caviar, caviar substitutes, tarama (carp roes), fried and sturgeon, lumpfish), also mixed with additional ingredients. It also includes the species added as part of a marinated eels. multi-ingredient food (all edible), e.g. salad, paste, sausage, sauce, spreads. Demersal Fish, Fresh Fresh raw whole fish including bones, skin, head, etc. -

Information on the Potential for Recovery of Cusk (Brosme Brosme) in Canadian Waters

Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat (CSAS) Research Document 2018/002 Maritimes Region Information on the Potential for Recovery of Cusk (Brosme brosme) in Canadian Waters L.E. Harris, M. Greenlaw, Q. McCurdy, and D. MacDonald Fisheries and Oceans Canada St. Andrews Biological Station 531 Brandy Cover Road St. Andrews, New Brunswick E5B 2L9 February 2018 Foreword This series documents the scientific basis for the evaluation of aquatic resources and ecosystems in Canada. As such, it addresses the issues of the day in the time frames required and the documents it contains are not intended as definitive statements on the subjects addressed but rather as progress reports on ongoing investigations. Research documents are produced in the official language in which they are provided to the Secretariat. Published by: Fisheries and Oceans Canada Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat 200 Kent Street Ottawa ON K1A 0E6 http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/csas-sccs/ [email protected] © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, 2018 ISSN 1919-5044 Correct citation for this publication: Harris, L.E., Greenlaw, M., McCurdy, D., and MacDonald, D. 2018. Information on the Potential for Recovery of Cusk (Brosme brosme) in Canadian Waters. DFO Can. Sci. Advis. Sec. Res. Doc. 2018/002. vi + 62 p. TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................................ V RÉSUMÉ ................................................................................................................................. -

The Fundy Survey

THE l!'UNDY SURVEY TFffii CUSK FISHEHY by Helen 1. Battle University of Wes t er n Ontario 1931 - 1 Tl ;.~ CUSK FISHERY Cont ents Nomencl a t ur e p . 2 Illustrati ons p. 3 Di s t i n gu ish ing Charact eristies p. 4 ~ e l at i v e I mportance of Fundy Oat oh p. 5 ni s t rihu t i on in Fun ' y r e a p . 8 .1et ;lOci s of Ca pture :p. 11 Fl u ct u a t i on s in t h e ]~ i s h e ry t hly p , 1 2 .n.ymuel p , 13 Ut i l i z a t i on p . 14 Recor ! en d a t i on s p , 1 5 - 1 THE CUSK FI S}~RY Contents Nomenclature p. 2 Illustrations p. 3 Distinguishing Charact eri stics p. 4 Rel a t i v e Importance of Fundy Catch p. 5 Di s t r ibu t i on in PUTIdy Area p. 8 met hods of Capture p. 11 Fluctuati ons in the Fishery Monthl y p. 12 )..nnuaJ. p. 13 Utilizati on p. 14 Becomme ndat i ons r 15 - 2 ... THE CUSK FISHERY Soientifio Name - Brosmius brosme (Mffller) Common Name - Cusk t Tusk t Torsk. This species of fish is generally known as the "Cusk". The terms ~lsk and Torsk while of European origin were apparent ly used in the Fundy region about a century ago t when a well known fishing ground in the Gulf of Maine was called the "Tusk Rock". -

Bulletin of the United States Fish Commission

BULLETIN OF THE UNITED STATES FISH COMMISSION. 297 48.-NOTES ON TEE BISEERIES OF QLOUCESTEB, MA%YACHUSETTS. By S. J. MARTIN. [From letters to Prof. S. F. Baird.] TIIE MACKEREL FISIIERP.-There hare been ten arrivals from the Gulf of Saint Lawrence bringing 3,490 barrels of salt mackerel. All report mackerel to be plenty in thevicinity of Prince Edward Island, and some of the mackerel catchers are going back to the bay. The large inaclrerel are scarce on this shore. I do not think mackerel come to the surface much, for tthe following reason : Capt. George H. Martin came in last Monday with 130 barrels of mackerel, 120 barrels of which he caught in one day, Ahgust; 16, on the western part of the Seal Island grounds. At sunrise the mackerel came to the surface as far as the eye could see. He set a small seine and a large one. In one hour after he hac1 taken tho 120 barrels, there was not n fivli to bo seen. He staid on the same ground eleven weeke, when the mackerel again came to the surface and Rtaid half an hour. Some of the vessels got good hauls. This has been the case off Mount Desert, Matinicus, and Isle au Haut. The mackerel are full of red-seed, called by the fishermen ‘(cayenne.” When the mackerel are plenty there are also many birds hovering over the water. PoRcIm.--Porgies are plenty now. Nine vessels ba,ited in Salem Barbor. There are two vessels at Salem seining porgies. The weirs at Portsmouth are full of porgies. -

Biology of the Striped Cusk-Eel, Ophidion Marginatum, from North Carolina

BULLETIN OF MARINE SCIENCE, 61(2): 327–342, 1997 BIOLOGY OF THE STRIPED CUSK-EEL, OPHIDION MARGINATUM, FROM NORTH CAROLINA Frank J. Schwartz ABSTRACT Nearly 2500 striped cusk-eels, Ophidion marginatum, were collected during a 6-yr intensive, 22-station trawl sampling of the Cape Fear River and nearby Sound and Atlan- tic Ocean areas in 1973-1978. Problems existed in confirming the specimens were O. marginatum rather than the similar appearing and ranging crested cusk-eel, O. welshi. The taxonomy remains unresolved but radiographs confirmed the North Carolina speci- mens were O. marginatum. Catch/effort and repetitive yearly sampling was compared by month, capture by size and station, morphometric relationships, age and growth, crest development, and food analyses. The study revealed O. marginatum was more active than previously believed, males and some females developed head crests, females were larger than males in size and many body-organ relationships, and females attain age 4 while males live for 3 yrs. O. marginatum feeds on a variety of foods, primarily crusta- ceans and fishes. Much remains to be learned of this elusive and systematically confus- ing species. Cohen and Nielsen (1978) reviewed the taxonomy of the Ophidiiform fishes, a group that includes the subfamily Ophidiinae (Pisces: Ophidiidae) which are mostly shelf- water inhabiting species (Gordon et al., 1984; Nelson, 1994). At least two similar and perhaps conspecific species pairs of cusk-eels, genus Ophidion, occur in the western Atlantic Ocean (Lea, 1980). One pair includes Ophidion (= Rissola) marginatum (DeKay, 1842) (striped cusk-eel) and O. welshi (Nichols and Breder, 1922) (crested cusk-eel). -

The Cod Family and Its Utilization

The Cod Family and Its Utilization JOHN J. RYAN Figure I.-Atlantic cod. Introduction without dried cod, for ships could carry cod, Gadus macrocephalus; 6) Atlantic no perishable food as staples. cod, Gadus morhua morhua; 7) Green Spanish explorers came to the New The cod family, from an economic land cod, Gadus ogac; 8) cusk, Brosme World to find gold and precious stones, point of view, is the most important of brosme; 9) fourbeard rockling, En but the French and Portuguese, fol all the families of fishes. The members chelyopus cimbrius; 10) burbot, Lota lowed by the English, crossed the At of the cod family are second only to the Iota; 11) haddock, Melanogrammus lantic to catch fish, especially the Atlan herring family in volume of commer aeglefinus; 12) silver hake (whiting), tic cod, Gadus morhua. In the 16th cial landings (Table 1). In contrast to Merluccius bilinearis; 13) Pacific hake, century, French and Portuguese vessels the herring family, which is often used Merluccius productus; 14) longfin fished the Grand Bank off Newfound for industrial purposes, almost all hake, Phycis chesteri; 15) luminous land. By the early 17th century, the of the cod, haddock, hakes, and whit hake, Steindachneria argentea; 16) red New England colonists were fishing for ings are used for human food. In hake, Urophycis chuss; 17) Gulf hake, cod (Fig. 1) in the local waters. In 1624 1976, 12,116,000 metric tons (t) Urophycis cirratus; 18) Carolina hake, "not less than 50 vessels from Glouces (26,710,000,000 pounds) of the cod Urophycis earlli; 19) southern hake, ter" fished with handlines off the coast.