Modeling the Costs and Benefits of Manufacturing Expedient Milling Tools

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prehistoric Grinding Tools As Metaphorical Traces of the Past Cecilia Lidström Holmberg

123 Prehistoric Grinding Tools as Metaphorical Traces of the Past Cecilia Lidström Holmberg The predominant interpretation of reciprocating grinding tools is generally couched in terms of low archaeological value, anonymity, simplicity, functionality and daily life of women. It is argued that biased opinions and a low form-variability have conspired to deny grinding tools all but superficial attention. Saddle-shaped grinding tools appear in the archaeological record in middle Sweden at the time of the Mesolithic — Neolithic transition. It is argued that Neolithic grinding tools are products of intentional design. Deliberate depositions in various ritual contexts reinforce the idea of grinding tools as prehistoric metaphors, with functional and symbolic meanings interlinked. Cecilia Lidström Hobnbert&, Department of Arcbaeology and Ancient Histo~; S:tEriks torg 5, Uppsala Universirv, SE-753 lO Uppsala, Swedett. THE OBSERVABLE, BUT INVISIBLE the past. Many grinding tools have probably GRINDING TOOLS not even been recognised as tools. The hand- Grinding tools of stone are common archaeo- ling of grinding and pounding tools found logical finds at nearly every prehistoric site. during excavations depends on the excavation The presence and recognition of these arte- policy, or rather on the excavators' sphere of facts have a long tradition within archaeology interest (see e.g. Kaliff 1997). (e.g. Bennet k Elton 1898;Hermelin 1912:67— As grinding tools of stone often are bulky 71; Miiller 1907:137,141; Rydbeck 1912:86- and heavy objects, they are rarely retained in 87). It is appropriate to acknowledge that large numbers (Hersch 1981:608).By tradi- previous generations of archaeologists to some tion, reciprocating grinding tools are archaeo- extent have raised questions related to the logically understood and treated as an anony- meaning and role of grinding tools, including mous category of objects. -

Morphological Changes in Starch Grains After Dehusking and Grinding

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Morphological changes in starch grains after dehusking and grinding with stone tools Received: 1 June 2018 Zhikun Ma1,2, Linda Perry3,4, Quan Li2 & Xiaoyan Yang2,5 Accepted: 8 November 2018 Research on the manufacture, use, and use-wear of grinding stones (including slabs and mullers) can Published: xx xx xxxx provide a wealth of information on ancient subsistence strategy and plant food utilization. Ancient residues extracted from stone tools frequently exhibit damage from processing methods, and modern experiments can replicate these morphological changes so that they can be better understood. Here, experiments have been undertaken to dehusk and grind grass grain using stone artifacts. To replicate ancient activities in northern China, we used modern stone tools to dehusk and grind twelve cultivars of foxtail millet (Setaria italica), two cultivars of broomcorn millet (Panicum miliaceum) and three varieties of green bristlegrass (Setaira viridis). The residues from both used and unused facets of the stone tools were then extracted, and the starch grains studied for morphological features and changes from the native states. The results show that (1) Dehusking did not signifcantly change the size and morphology of millet starch grains; (2) After grinding, the size of millet starch grains increases up to 1.2 times larger than native grains, and a quarter of the ground millet starch grains bore surface damage and also exhibited distortion of the extinction cross. This indicator will be of signifcance in improving the application of starch grains to research in the functional inference of grinding stone tools, but we are unable to yet distinguish dehusked forms from native. -

ATSR 4 15 Stols.Indd 112 17/01/2012 10:18 to Prepare White Excellent…

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) 'To prepare white excellent...': reconstructions investigating the influence of washing, grinding and decanting of stack-process lead white on pigment composition and particle size Stols-Witlox, M.; Megens, L.; Carlyle, L. Publication date 2012 Document Version Final published version Published in The artist's process: technology and interpretation Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Stols-Witlox, M., Megens, L., & Carlyle, L. (2012). 'To prepare white excellent...': reconstructions investigating the influence of washing, grinding and decanting of stack- process lead white on pigment composition and particle size. In S. Eyb-Green, J. H. Townsend, M. Clarke, J. Nadolny, & S. Kroustallis (Eds.), The artist's process: technology and interpretation (pp. 112-129). Archetype. http://www.clericus.org/atsr/postprints4.htm General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library -

New Approaches to Old Stones Approaches to Anthropological Archaeology Series Editor: Thomas E

New Approaches to Old Stones Approaches to Anthropological Archaeology Series Editor: Thomas E. Levy, University of California, San Diego Editorial Board: Guillermo Algaze, University of California, San Diego Geoffrey E. Braswell (University of California, San Diego) Paul S. Goldstein, University of California, San Diego Joyce Marcus, University of Michigan This series recognizes the fundamental role that anthropology now plays in archaeology and also integrates the strengths of various research paradigms that characterize archaeology on the world scene today. Some of these different approaches include ‘New’ or ‘Processual’ archaeology, ‘Post- Processual’, evolutionist, cognitive, symbolic, Marxist, and historical archaeologies. Anthropological archaeology accomplishes its goals by taking into account the cultural and, when possible, historical context of the material remains being studied. This involves the development of models concerning the formative role of cognition, symbolism, and ideology in human societies to explain the more material and economic dimensions of human culture that are the natural purview of archaeological data. It also involves an understanding of the cultural ecology of the societies being studied, and of the limitations and opportunities that the environment (both natural and cultural) imposes on the evolution or devolution of human societies. Based on the assumption that cultures never develop in isolation, Anthropological Archaeology takes a regional approach to tackling fundamental issues concerning past cultural -

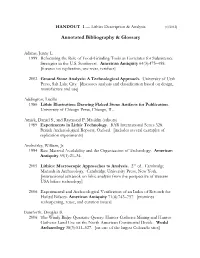

Lithic Analysis Bibliography & Glossary

HANDOUT 1 — Lithics Description & Analysis [4/2012] Annotated Bibliography & Glossary Adams, Jenny L. 1999 Refocusing the Role of Food-Grinding Tools as Correlates for Subsistence Strategies in the U.S. Southwest. American Antiquity 64(3):475–498. [focuses on replication, use wear, residues] 2002 Ground Stone Analysis: A Technological Approach. University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City. [discusses analysis and classification based on design, manufacture and use] Addington, Lucille 1986 Lithic Illustration: Drawing Flaked Stone Artifacts for Publication. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL. Amick, Daniel S., and Raymond P. Mauldin (editors) 1989 Experiments in Lithic Technology. BAR International Series 528. British Archaeological Reports, Oxford. [includes several examples of replication experiments] Andrefsky, William, Jr. 1994 Raw-Material Availability and the Organization of Technology. American Antiquity 59(1):21–34. 2005 Lithics: Macroscopic Approaches to Analysis. 2nd ed. Cambridge Manuals in Archaeology. Cambridge University Press, New York. [instructional textbook on lithic analysis from the perspective of western USA biface technology] 2006 Experimental and Archaeological Verification of an Index of Retouch for Hafted Bifaces. American Antiquity 71(4):743–757. [examines resharpening, reuse, and curation issues] Bamforth, Douglas B. 2006 The Windy Ridge Quartzite Quarry: Hunter-Gatherer Mining and Hunter- Gatherer Land Use on the North American Continental Divide. World Archaeology 38(3):511–527. [on one of the largest Colorado sites] Barnett, Franklin 1991 Dictionary of Prehistoric Indian Artifacts of the American Southwest. Northland Publishing Co., Flagstaff, AZ. Barton, C. Michael 1996 Beyond the Graver: Reconsidering Burin Function. Journal of Field Archaeology 23(1):111–125. [well-illustrated, but specific topic] Benedict, James B. -

Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia

SIBERIAN BRANCH OF THE RUSSIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES INSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY AND ETHNOGRAPHY ARCHAEOLOGY, ETHNOLOGY & ANTHROPOLOGY OF EURASIA Volume 47, No. 4, 2019 DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2019.47.4 Published in Russian and English CONTENTS PALEOENVIRONMENT. THE STONE AGE 3 A.V. Vishnevskiy, K.K. Pavlenok, M.B. Kozlikin, V.A. Ulyanov, A.P. Derevianko, and M.V. Shunkov. A Neanderthal Refugium in the Eastern Adriatic 16 А.А. Anoikin, G.D. Pavlenok, V.M. Kharevich, Z.K. Taimagambetov, A.V. Shalagina, S.A. Gladyshev, V.A. Ulyanov, R.S. Duvanbekov, and M.V. Shunkov. Ushbulak—A New Stratifi ed Upper Paleolithic Site in Northeastern Kazakhstan 30 V.E. Medvedev and I.V. Filatova. Archaeological Findings on Suchu Island (Excavation Area I, 1975) THE METAL AGES AND MEDIEVAL PERIOD 43 I.A. Kukushkin and E.A. Dmitriev. Burial with a Chariot at the Tabyldy Cemetery, Central Kazakhstan 53 N.V. Basova, A.V. Postnov, A.L. Zaika, and V.I. Molodin. Objects of Portable Art from a Bronze Age Cemetery at Tourist-2 66 K.A. Kolobova, A.Y. Fedorchenko, N.V. Basova, A.V. Postnov, V.S. Kovalev, P.V. Chistyakov, and V.I. Molodin. The Use of 3D-Modeling for Reconstructing the Appearance and Function of Non-Utilitarian Items (the Case of Anthropomorphic Figurines from Tourist-2) 77 A.P. Borodovsky and A.Y. Trufanov. Ceramic Protomes of Horses from Late Bronze to Early Iron Age Sites in the Southern Taiga Zone of Siberia 85 N.V. Fedorova and A.V. Baulo. “Portrait” Medallions from the Kazym Hoard 93 M. -

Guidelines for Improving Full-Depth Repair of PCC Pavements in Wisconsin

DISCLAIMER This research was funded through the Wisconsin Highway Research Program by the Wisconsin Department of Transportation and the Federal Highway Administration under Project # 0092-07-03. The contents of this report reflect the views of the authors who are responsible for the facts and accuracy of the data presented herein. The contents do not necessarily reflect the official views of the Wisconsin Department of Transportation or the Federal Highway Administration at the time of publication. This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The United States Government assumes no liability for its contents or use thereof. This report does not constitute a standard, specification or regulation. The United States Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. Trade and manufacturers’ names appear in this report only because they are considered essential to the object of the document. ii iii Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient’s Catalog No. WHRP 08-02 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date GUIDELINES FOR IMPROVING FULL-DEPTH REPAIR OF PCC March 2008 PAVEMENTS IN WISCONSIN 6. Performing Organization Code 7. Authors 8. Performing Organization Report No. Leslie Titus-Glover and Michael I. Darter, Ph.D, P.E. 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) Applied Research Associates, Inc. 100 Trade Centre Dr., Suite 200 11. Contract or Grant No. Champaign, IL 61820-7233 WisDOT SPR# 0092-07-03 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period Covered Wisconsin Department of Transportation Final Report (10/06 – 03/08) Division of Business Services Research Coordination Section 14. -

Raw Material Economy and Mobility in the Rhenish Allerød Rohmaterialökonomie Und Mobilität Im Rheinischen Allerød Hannah Parow-Souchon & Martin Heinen

Quartär Internationales Jahrbuch zur Eiszeitalter- und Steinzeitforschung International Yearbook for Ice Age and Stone Age Research Band – Volume 64 Edited by Sandrine Costamagno, Thomas Hauck, Zsolt Mester, Luc Moreau, Philip R. Nigst, Andreas Pastoors, Daniel Richter, Isabell Schmidt, Martin Street, Yvonne Tafelmaier, Elaine Turner, Thorsten Uthmeier Verlag Marie Leidorf GmbH . Rahden/Westf. 2017 287 Seiten mit 187 Abbildungen Manuskript-Richtlinien und weitere Informationen unter http://www.quartaer.eu Instructions for authors and supplementary information at http://www.quartaer.eu Bibliographische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Costamagno, Sandrine / Hauck, Thomas / Mester, Zsolt / Moreau, Luc / Nigst, Philip R. / Pastoors, Andreas / Richter, Daniel / Schmidt, Isabell / Street, Martin / Yvonne Tafelmaier / Turner, Elaine / Thorsten Uthmeier (Eds.): Quartär: Internationales Jahrbuch zur Eiszeitalter- und Steinzeitforschung; Band 64 International Yearbook for Ice Age and Stone Age Research; Volume 64 Rahden/Westf.: Leidorf, 2017 ISBN: 978-3-86757-930-8 Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliographie. Detaillierte bibliographische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.ddb.de abrufbar. Gedruckt auf alterungsbeständigem Papier Alle Rechte vorbehalten © 2017 Verlag Marie Leidorf GmbH Geschäftsführer: Dr. Bert Wiegel Stellerloh 65 - D-32369 Rahden/Westf. Tel: +49/(0)5771/ 9510-74 Fax: +49/(0)5771/ 9510-75 E-Mail: [email protected] Internet: http://www.vml.de ISBN 978-3-86757-930-8 ISSN 0375-7471 Kein Teil des Buches darf in irgendeiner Form (Druck, Fotokopie, CD-ROM, DVD, Internet oder einem anderen Verfahren) ohne schriftliche Genehmigung des Verlages Marie Leidorf GmbH reproduziert werden oder unter Verwendung elektronischer Systeme verarbeitet, vervielfältigt oder verbreitet werden. Umschlagentwurf: Werner Müller, CH-Neuchâtel, unter Mitwirkung der Herausgeber Redaktion: Sandrine Costamagno, F-Toulouse, Thomas Hauck, D-Köln, Zsolt Mester, H-Budapest, Luc Moreau, D-Neuwied, Philip R. -

Grinding-Stone Implements in the Eastern African Pastoral Neolithic

Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa ISSN: 0067-270X (Print) 1945-5534 (Online) Journal homepage: https://tandfonline.com/loi/raza20 Grinding-stone implements in the eastern African Pastoral Neolithic Anna Shoemaker & Matthew I.J. Davies To cite this article: Anna Shoemaker & Matthew I.J. Davies (2019) Grinding-stone implements in the eastern African Pastoral Neolithic, Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa, 54:2, 203-220, DOI: 10.1080/0067270X.2019.1619284 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/0067270X.2019.1619284 © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group Published online: 08 Jul 2019. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 309 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=raza20 AZANIA: ARCHAEOLOGICAL RESEARCH IN AFRICA 2019, VOL. 54, NO. 2, 203–220 https://doi.org/10.1080/0067270X.2019.1619284 Grinding-stone implements in the eastern African Pastoral Neolithic Anna Shoemaker a and Matthew I.J. Daviesb aDepartment of Archaeology and Ancient History, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden; bInstitute for Global Prosperity, University College London, London, United Kingdom ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY Grinding-stone tools are a poorly utilised source of archaeological Received 25 May 2017 information in eastern Africa. Their presence is noted in multiple Accepted 16 February 2019 contexts, including both domestic and funerary, yet the inferences KEYWORDS drawn from them are often limited. This short review paper grinding-stone tools; Pastoral presents existing information on grinding-stone tools (and stone Neolithic; funerary bowls) from Pastoral Neolithic (PN) contexts in eastern Africa. -

Appendix J Archaeological Survey

Appendix J Archaeological Survey Supplementary Archaeological and Historic Surveys for the Open Cut Pit Project McArthur River Mine, NT Draft report A report for URS on behalf of McArthur River Mines Prepared by: Begnaze Pty. Ltd. Christine Crassweller Begnaze Pty Ltd 8 Wanguri Tce Wanguri NT 0810 September 2005 1 SUMMARY The Draft Environmental Impact Statement for the project stated that McArthur River Mine (MRM) would undertake further archaeological surveys to identify areas where there is a higher potential for the presence of archaeological and historic heritage and that recommendations are made to mitigate any loss. This report by Begnaze Pty Ltd describes the archaeological surveys over areas that will be disturbed by the proposed open cut pit at MRM and the subsequent recommendations that were based on the survey and prior archaeological work carried out at the mine. The survey located one archaeological site, MRM4, and forty two background scatters of isolated artefacts that will be disturbed by the development. Two other archaeological sites MRM1 and MRM2 located during the archaeological surveys for Test Pit Project will also be destroyed. The results of the survey indicate that there is a very low potential for locating further sites in the areas to be disturbed by the Open Cut Project. While there is a high potential for the presence of unidentified isolated artefacts on and under the areas to be disturbed, their archaeological significance is deemed to be very low. Therefore it is recommended that the presence of an archaeologist during the clearing operations for the Open Cut Project will not mitigate the loss of any significant archaeological knowledge. -

Analysis of Flaked Stone Lithics from Virgin Anasazi Sites Near Mt

ANALYSIS OF FLAKED STONE LITHICS FROM VIRGIN ANASAZI SITES NEAR MT. TRUMBULL, ARIZONA STRIP by Cheryl Marie Martin Bachelor of Science in Education University of North Texas 1989 Master of Science University of North Texas 1991 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts Degree in Anthropology Department of Anthropology and Ethnic Studies College of Liberal Arts Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas December 2009 THE GRADUATE COLLEGE We recommend that the thesis prepared under our supervision by Cheryl Marie Martin entitled Analysis of Flaked Stone Lithics from Virgin Anasazi Sites near Mt. Trumbull, Arizona Strip be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Anthropology Barbara Roth, Committee Chair Karen Harry, Committee Member Paul Buck, Committee Member Stephen Rowland, Graduate Faculty Representative Ronald Smith, Ph. D., Vice President for Research and Graduate Studies and Dean of the Graduate College December 2009 ii ABSTRACT Analysis of Flaked Stone Lithics from Virgin Anasazi Sites near Mt. Trumbull, Arizona Strip by Cheryl Marie Martin Dr. Barbara Roth, Thesis Committee Chair Professor of Anthropology University of Nevada, Las Vegas This thesis examines flaked stone tools that were used by the Virgin Anasazi and the debitage resulting from their manufacture at six sites in the Mt. Trumbull region in order to infer past human behavior. The behaviors being examined include activities carried out at sites, the processing and use of raw stone materials, and patterns of regional exchange. I have applied obsidian sourcing technology and an analysis of flaked stone attributes. -

The Stone Implements and Wrist-Guards of the Bell Beaker Cemetery ..., VAMZ, 3

TUNDE HORVATH: The stone implements and wrist-guards of the Bell Beaker cemetery ..., VAMZ, 3. s., L (2017) 71 TÜNDE HORVÁTH Universität Wien Historisch-Kulturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät Institut für Urgeschichte und Historische Archäologie Franz-Klein-Gasse 1 A ‒ 1190 Wien e-mail: [email protected] The stone implements and wrist-guards of the Bell Beaker cemetery of Budakalász (M0/12 site) UDK / UDC: 903.01(439.153 Budakalász)’’6373’’ Izvorni znanstveni rad / Original scientific paper In this article I investigate the stone finds of published Hungarian and European Bell the Bell Beaker cemetery of Budakalász from Beaker sites. archaeological and petrographic points of Keywords: Early Bronze Age, Bell Beaker view. For the first time in Hungary I describe Culture, Budapest-Csepel group, stone imple- the finds in the terms of international typol- ments, biritual cemetery. ogy, and compare the inventory with other 1. IntroduCTION In this article1 I investigate the stone imple- ments of the Bell Beaker site of Budakalász.2 of the cemetery from archaeological and The site consists of two parts: a cemetery macroscopicI describe and petrographic evaluate thepoints stone of view.finds with 1070 graves (biritual inhumations, Because of the large distribution area of urngraves and scattered urngraves, empty the Bell Beaker Culture, I have made my gravepits / symbolic burials or cenotaphs), analyses at the levels of the site, the region and the settlement part.3 (Budapest-Csepel group / Budapest dis- trict) and the country (Hungary) and also 1 The article was supported by the Lise Meitner fellowship considered the whole distribution area (project M 2003-G25 / AM 0200321) of FWF (Fonds zur Förderung der wissenschaftlichen Forschung).