Back to the Grindstone? the Archaeological

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prehistoric Grinding Tools As Metaphorical Traces of the Past Cecilia Lidström Holmberg

123 Prehistoric Grinding Tools as Metaphorical Traces of the Past Cecilia Lidström Holmberg The predominant interpretation of reciprocating grinding tools is generally couched in terms of low archaeological value, anonymity, simplicity, functionality and daily life of women. It is argued that biased opinions and a low form-variability have conspired to deny grinding tools all but superficial attention. Saddle-shaped grinding tools appear in the archaeological record in middle Sweden at the time of the Mesolithic — Neolithic transition. It is argued that Neolithic grinding tools are products of intentional design. Deliberate depositions in various ritual contexts reinforce the idea of grinding tools as prehistoric metaphors, with functional and symbolic meanings interlinked. Cecilia Lidström Hobnbert&, Department of Arcbaeology and Ancient Histo~; S:tEriks torg 5, Uppsala Universirv, SE-753 lO Uppsala, Swedett. THE OBSERVABLE, BUT INVISIBLE the past. Many grinding tools have probably GRINDING TOOLS not even been recognised as tools. The hand- Grinding tools of stone are common archaeo- ling of grinding and pounding tools found logical finds at nearly every prehistoric site. during excavations depends on the excavation The presence and recognition of these arte- policy, or rather on the excavators' sphere of facts have a long tradition within archaeology interest (see e.g. Kaliff 1997). (e.g. Bennet k Elton 1898;Hermelin 1912:67— As grinding tools of stone often are bulky 71; Miiller 1907:137,141; Rydbeck 1912:86- and heavy objects, they are rarely retained in 87). It is appropriate to acknowledge that large numbers (Hersch 1981:608).By tradi- previous generations of archaeologists to some tion, reciprocating grinding tools are archaeo- extent have raised questions related to the logically understood and treated as an anony- meaning and role of grinding tools, including mous category of objects. -

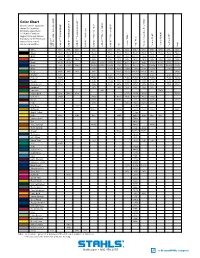

Color Chart ® ® ® ® Closest Pantone® Equivalent Shown

™ ™ II ® Color Chart ® ® ® ® Closest Pantone® equivalent shown. Due to printing limitations, colors shown 5807 Reflective ® ® ™ ® ® and Pantone numbers ® ™ suggested may vary from ac- ECONOPRINT GORILLA GRIP Fashion-REFLECT Reflective Thermo-FILM Thermo-FLOCK Thermo-GRIP ® ® ® ® ® ® ® tual colors. For the truest color ® representation, request Scotchlite our material swatches. ™ CAD-CUT 3M CAD-CUT CAD-CUT CAD-CUT CAD-CUT CAD-CUT CAD-CUT Felt Perma-TWILL Poly-TWILL Thermo-FILM Thermo-FLOCK Thermo-GRIP Vinyl Pressure Sensitive Poly-TWILL Sensitive Pressure CAD-CUT White White White White White White White White White* White White White White White Black Black Black Black Black Black Black Black Black* Black Black Black Black Black Gold 1235C 136C 137C 137C 123U 715C 1375C* 715C 137C 137C 116U Red 200C 200C 703C 186C 186C 201C 201C 201C* 201C 186C 186C 186C 200C Royal 295M 294M 7686C 2747C 7686C 280C 294C 294C* 294C 7686C 2758C 7686C 654C Navy 296C 2965C 7546C 5395M 5255C 5395M 276C 532C 532C* 532C 5395M 5255C 5395M 5395C Cool Gray Warm Gray Gray 7U 7539C 7539C 415U 7538C 7538C* 7538C 7539C 7539C 2C Kelly 3415C 341C 340C 349C 7733C 7733C 7733C* 7733C 349C 3415C Orange 179C 1595U 172C 172C 7597C 7597C 7597C* 7597C 172C 172C 173C Maroon 7645C 7645C 7645C Black 5C 7645C 7645C* 7645C 7645C 7645C 7449C Purple 2766C 7671C 7671C 669C 7680C 7680C* 7680C 7671C 7671C 2758U Dark Green 553C 553C 553C 447C 567C 567C* 567C 553C 553C 553C Cardinal 201C 188C 195C 195C* 195C 201C Emerald 348 7727C Vegas Gold 616C 7502U 872C 4515C 4515C 4515C 7553U Columbia 7682C 7682C 7459U 7462U 7462U* 7462U 7682C Brown Black 4C 4675C 412C 412C Black 4C 412U Pink 203C 5025C 5025C 5025C 203C Mid Blue 2747U 2945U Old Gold 1395C 7511C 7557C 7557C 1395C 126C Bright Yellow P 4-8C Maize 109C 130C 115U 7408C 7406C* 7406C 115U 137C Canyon Gold 7569C Tan 465U Texas Orange 7586C 7586C 7586C Tenn. -

RAL COLOR CHART ***** This Chart Is to Be Used As a Guide Only. Colors May Appear Slightly Different ***** Green Beige Purple V

RAL COLOR CHART ***** This Chart is to be used as a guide only. Colors May Appear Slightly Different ***** RAL 1000 Green Beige RAL 4007 Purple Violet RAL 7008 Khaki Grey RAL 4008 RAL 7009 RAL 1001 Beige Signal Violet Green Grey Tarpaulin RAL 1002 Sand Yellow RAL 4009 Pastel Violet RAL 7010 Grey RAL 1003 Signal Yellow RAL 5000 Violet Blue RAL 7011 Iron Grey RAL 1004 Golden Yellow RAL 5001 Green Blue RAL 7012 Basalt Grey Ultramarine RAL 1005 Honey Yellow RAL 5002 RAL 7013 Brown Grey Blue RAL 1006 Maize Yellow RAL 5003 Saphire Blue RAL 7015 Slate Grey Anthracite RAL 1007 Chrome Yellow RAL 5004 Black Blue RAL 7016 Grey RAL 1011 Brown Beige RAL 5005 Signal Blue RAL 7021 Black Grey RAL 1012 Lemon Yellow RAL 5007 Brillant Blue RAL 7022 Umbra Grey Concrete RAL 1013 Oyster White RAL 5008 Grey Blue RAL 7023 Grey Graphite RAL 1014 Ivory RAL 5009 Azure Blue RAL 7024 Grey Granite RAL 1015 Light Ivory RAL 5010 Gentian Blue RAL 7026 Grey RAL 1016 Sulfer Yellow RAL 5011 Steel Blue RAL 7030 Stone Grey RAL 1017 Saffron Yellow RAL 5012 Light Blue RAL 7031 Blue Grey RAL 1018 Zinc Yellow RAL 5013 Cobolt Blue RAL 7032 Pebble Grey Cement RAL 1019 Grey Beige RAL 5014 Pigieon Blue RAL 7033 Grey RAL 1020 Olive Yellow RAL 5015 Sky Blue RAL 7034 Yellow Grey RAL 1021 Rape Yellow RAL 5017 Traffic Blue RAL 7035 Light Grey Platinum RAL 1023 Traffic Yellow RAL 5018 Turquiose Blue RAL 7036 Grey RAL 1024 Ochre Yellow RAL 5019 Capri Blue RAL 7037 Dusty Grey RAL 1027 Curry RAL 5020 Ocean Blue RAL 7038 Agate Grey RAL 1028 Melon Yellow RAL 5021 Water Blue RAL 7039 Quartz Grey -

Chapter 1 Definitions and Classifications for Fruit and Vegetables

Chapter 1 Definitions and classifications for fruit and vegetables In the broadest sense, the botani- Botanical and culinary cal term vegetable refers to any plant, definitions edible or not, including trees, bushes, vines and vascular plants, and Botanical definitions distinguishes plant material from ani- Broadly, the botanical term fruit refers mal material and from inorganic to the mature ovary of a plant, matter. There are two slightly different including its seeds, covering and botanical definitions for the term any closely connected tissue, without vegetable as it relates to food. any consideration of whether these According to one, a vegetable is a are edible. As related to food, the plant cultivated for its edible part(s); IT botanical term fruit refers to the edible M according to the other, a vegetable is part of a plant that consists of the the edible part(s) of a plant, such as seeds and surrounding tissues. This the stems and stalk (celery), root includes fleshy fruits (such as blue- (carrot), tuber (potato), bulb (onion), berries, cantaloupe, poach, pumpkin, leaves (spinach, lettuce), flower (globe tomato) and dry fruits, where the artichoke), fruit (apple, cucumber, ripened ovary wall becomes papery, pumpkin, strawberries, tomato) or leathery, or woody as with cereal seeds (beans, peas). The latter grains, pulses (mature beans and definition includes fruits as a subset of peas) and nuts. vegetables. Definition of fruit and vegetables applicable in epidemiological studies, Fruit and vegetables Edible plant foods excluding -

Morphological Changes in Starch Grains After Dehusking and Grinding

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Morphological changes in starch grains after dehusking and grinding with stone tools Received: 1 June 2018 Zhikun Ma1,2, Linda Perry3,4, Quan Li2 & Xiaoyan Yang2,5 Accepted: 8 November 2018 Research on the manufacture, use, and use-wear of grinding stones (including slabs and mullers) can Published: xx xx xxxx provide a wealth of information on ancient subsistence strategy and plant food utilization. Ancient residues extracted from stone tools frequently exhibit damage from processing methods, and modern experiments can replicate these morphological changes so that they can be better understood. Here, experiments have been undertaken to dehusk and grind grass grain using stone artifacts. To replicate ancient activities in northern China, we used modern stone tools to dehusk and grind twelve cultivars of foxtail millet (Setaria italica), two cultivars of broomcorn millet (Panicum miliaceum) and three varieties of green bristlegrass (Setaira viridis). The residues from both used and unused facets of the stone tools were then extracted, and the starch grains studied for morphological features and changes from the native states. The results show that (1) Dehusking did not signifcantly change the size and morphology of millet starch grains; (2) After grinding, the size of millet starch grains increases up to 1.2 times larger than native grains, and a quarter of the ground millet starch grains bore surface damage and also exhibited distortion of the extinction cross. This indicator will be of signifcance in improving the application of starch grains to research in the functional inference of grinding stone tools, but we are unable to yet distinguish dehusked forms from native. -

Green Beige Beige Sand Yellow Signal Yellow Golden Yellow Honey Yellow Maize Yellow Daffodil Yellow Brown Beige Lemon Yellow

GREEN BEIGE BEIGE SAND YELLOW SIGNAL YELLOW GOLDEN YELLOW DAFFODIL HONEY YELLOW MAIZE YELLOW YELLOW BROWN BEIGE LEMON YELLOW OYSTER WHITE IVORY LIGHT IVORY SULFUR YELLOW SAFFRON YELLOW ZINC YELLOW GREY BEIGE OLIVE YELLOW COLZA YELLOW TRAFFIC YELLOW LUMINOUS OCHRE YELLOW YELLOW CURRY MELON YELLOW BROOM YELLOW DAHLIA YELLOW PASTEL YELLOW PEARL BEIGE PEARL GOLD SUN YELLOW YELLOW ORANGE RED ORANGE VERMILION PASTEL ORANGE PURE ORANGE LUMINOUS LUMINOUS BRIGHT RED ORANGE BRIGHT ORANGE ORANGE TRAFFIC ORANGE SIGNAL ORANGE DEEP ORANGE SALMON ORANGE PEARL ORANGE FLAME RED SIGNAL RED CARMINE RED RUBY RED PURPLE RED WINE RED BLACK RED OXIDE RED BROWN RED BEIGE RED TOMATO RED ANTIQUE PINK LIGHT PINK CORAL RED ROSE LUMINOUS STRAWBERRY RED TRAFFIC RED SALMON PINK LUMINOUS RED BRIGHT RED RASPBERRY RED PURE RED ORIENT RED PEARL RUBY RED PEARL PINK RED LILAC RED VIOLET HEATHER VIOLET CLARET VIOLET BLUE LILAC TRAFFIC PURPLE PURPLE VIOLET SIGNAL VIOLET PASTEL VIOLET TELEMAGENTA PEARL BLACK PEARL VIOLET BERRY ULTRAMARINE VIOLET BLUE GREEN BLUE BLUE SAPHIRE BLUE BLACK BLUE SIGNAL BLUE BRILLANT BLUE GREY BLUE AZURE BLUE GENTIAN BLUE STEEL BLUE LIGHT BLUE COBALT BLUE PIGEON BLUE SKY BLUE TRAFFIC BLUE TURQUOISE BLUE CAPRI BLUE OCEAN BLUE WATER BLUE PEARL GENTIAN PEARL NIGHT NIGHT BLUE DISTANT BLUE PASTEL BLUE BLUE BLUE PATINA GREEN EMERALD GREEN LEAF GREEN OLIVE GREEN BLUE GREEN MOSS GREEN GREY OLIVE BOTTLE GREEN BROWN GREEN FIR GREEN GRASS GREEN RESEDA GREEN BLACK GREEN REED GREEN YELLOW OLIVE TURQUOISE BLACK OLIVE GREEN MAY GREEN YELLOW GREEN PASTEL GREEN CHROME -

Maize Variety Choices and Mayan Foodways in Rural Yucatan, Mexico

All Maize Is Not Equal: Maize Variety Choices and Mayan Foodways in Rural Yucatan, Mexico John Tuxill, Luis Arias Reyes, Luis Latournerie Moreno, and Vidal Cob Uicab, Devra I. Jarvis Introduction Foodways have changed substantially over the past several centuries in the Yucatan Peninsula and other areas of Mesoamerica, but one constant is the presence of maize (Zea mays) at the heart of rural economy, ecology, and culture. The domes- tication and diversification of maize – the world’s most productive grain crop – by indigenous farmers ranks as one of the greatest accomplishments of plant breeding. Remains of ancient maize cobs in the archeological record suggest that maize was first brought into cultivation roughly 7,000 years ago in the highlands of central Mexico, where its closest wild relative, teosinte (Zea mays ssp. parviglumis), also grows (Wilkes 1977; McClung de Tapia 1997; Smith 2001; Piperno and Flannery 2001; Matsuoka et al. 2002). From that starting point, maize was gradually selected and diversified over time by farmers into an impressive array of different forms, sizes, and colors. Maize appears to spread out of central Mexico rapidly in the context of regional trade and exchange networks, and farmers selected and adapted maize populations to thrive in new environments. Archeobotanical evidence from northern Belize suggests maize arrived in the Yucatan Peninsula by about 5,000 years B.P. (Colunga-García Marín and Zizumbo-Villarreal 2004). As maize spread and evolved in the Yucatan at the hands of Mayan farmers, it achieved a symbolic, ceremonial, ecological, and economic importance surpassing that of any other plant or natural resource in the Mayan world. -

NARANI RED OCHRE MINING PROJECT (M.L No

NARANI RED OCHRE MINING PROJECT (M.L No. 44/2006, ML Area: 259.0 ha.) Located at near Village: Narani, Tehsil: Choti Sadari, District: Pratapgarh (Raj.) Pre Feasibility Report PRE-FEASIBILITY REPORT (As per Ministry of Environment and Forests Letter dated: 30-12-2010) 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Particulars Details Project name Proposed expansion project of Narani Red Ochre Mine Location Near Village: Narani, Tehsil: Choti Sadri & District- Pratapgarh, Rajasthan (M.L. No.: 44/2006) GPS Co-Ordinates of S. Reference Latitude Longitude Project No Point No. FRP 24°24'47.39” 74°46'43.95” 1 A 24°24'54.57” 74°47'2.8” 2 B 24°25'16.47” 74°46'27.23” 3 C 24°26'14.37” 74°47'9.74” 4 D 24°25'52.47” 74°47'45.32” Toposheet No. Falls in survey of India Toposheet No.- 45L/15 Total Mine area 259.0 Hectare (Govt. waste land: 60.2966 ha., Pvt. Land: 165.2862 ha., Grazing land: 33.4172 ha.) Total Reserves 4,29,38,953 MT (Mineable Reserves: 3,64,98,112 MT) Capacity/year Proposed production – 5,88,236 MT (ROM) Life of Mine ~73 years Estimated project cost 2 Crore/- EMP Cost 4.40 Lac/- per annum Power Requirement Electric connection is already taken for office purpose. Fuel Requirement As per requirement, will be made available by contractor Alternate source of power is DG Set of 63 KVA available in the DG Set mining lease area for office purpose. Highest and Lowest S. No. Particulars Elevation (mRL) Elevation 1. -

Air Force Blue (Raf) {\Color{Airforceblueraf}\#5D8aa8

Air Force Blue (Raf) {\color{airforceblueraf}\#5d8aa8} #5d8aa8 Air Force Blue (Usaf) {\color{airforceblueusaf}\#00308f} #00308f Air Superiority Blue {\color{airsuperiorityblue}\#72a0c1} #72a0c1 Alabama Crimson {\color{alabamacrimson}\#a32638} #a32638 Alice Blue {\color{aliceblue}\#f0f8ff} #f0f8ff Alizarin Crimson {\color{alizarincrimson}\#e32636} #e32636 Alloy Orange {\color{alloyorange}\#c46210} #c46210 Almond {\color{almond}\#efdecd} #efdecd Amaranth {\color{amaranth}\#e52b50} #e52b50 Amber {\color{amber}\#ffbf00} #ffbf00 Amber (Sae/Ece) {\color{ambersaeece}\#ff7e00} #ff7e00 American Rose {\color{americanrose}\#ff033e} #ff033e Amethyst {\color{amethyst}\#9966cc} #9966cc Android Green {\color{androidgreen}\#a4c639} #a4c639 Anti-Flash White {\color{antiflashwhite}\#f2f3f4} #f2f3f4 Antique Brass {\color{antiquebrass}\#cd9575} #cd9575 Antique Fuchsia {\color{antiquefuchsia}\#915c83} #915c83 Antique Ruby {\color{antiqueruby}\#841b2d} #841b2d Antique White {\color{antiquewhite}\#faebd7} #faebd7 Ao (English) {\color{aoenglish}\#008000} #008000 Apple Green {\color{applegreen}\#8db600} #8db600 Apricot {\color{apricot}\#fbceb1} #fbceb1 Aqua {\color{aqua}\#00ffff} #00ffff Aquamarine {\color{aquamarine}\#7fffd4} #7fffd4 Army Green {\color{armygreen}\#4b5320} #4b5320 Arsenic {\color{arsenic}\#3b444b} #3b444b Arylide Yellow {\color{arylideyellow}\#e9d66b} #e9d66b Ash Grey {\color{ashgrey}\#b2beb5} #b2beb5 Asparagus {\color{asparagus}\#87a96b} #87a96b Atomic Tangerine {\color{atomictangerine}\#ff9966} #ff9966 Auburn {\color{auburn}\#a52a2a} #a52a2a Aureolin -

ATSR 4 15 Stols.Indd 112 17/01/2012 10:18 to Prepare White Excellent…

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) 'To prepare white excellent...': reconstructions investigating the influence of washing, grinding and decanting of stack-process lead white on pigment composition and particle size Stols-Witlox, M.; Megens, L.; Carlyle, L. Publication date 2012 Document Version Final published version Published in The artist's process: technology and interpretation Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Stols-Witlox, M., Megens, L., & Carlyle, L. (2012). 'To prepare white excellent...': reconstructions investigating the influence of washing, grinding and decanting of stack- process lead white on pigment composition and particle size. In S. Eyb-Green, J. H. Townsend, M. Clarke, J. Nadolny, & S. Kroustallis (Eds.), The artist's process: technology and interpretation (pp. 112-129). Archetype. http://www.clericus.org/atsr/postprints4.htm General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library -

New Approaches to Old Stones Approaches to Anthropological Archaeology Series Editor: Thomas E

New Approaches to Old Stones Approaches to Anthropological Archaeology Series Editor: Thomas E. Levy, University of California, San Diego Editorial Board: Guillermo Algaze, University of California, San Diego Geoffrey E. Braswell (University of California, San Diego) Paul S. Goldstein, University of California, San Diego Joyce Marcus, University of Michigan This series recognizes the fundamental role that anthropology now plays in archaeology and also integrates the strengths of various research paradigms that characterize archaeology on the world scene today. Some of these different approaches include ‘New’ or ‘Processual’ archaeology, ‘Post- Processual’, evolutionist, cognitive, symbolic, Marxist, and historical archaeologies. Anthropological archaeology accomplishes its goals by taking into account the cultural and, when possible, historical context of the material remains being studied. This involves the development of models concerning the formative role of cognition, symbolism, and ideology in human societies to explain the more material and economic dimensions of human culture that are the natural purview of archaeological data. It also involves an understanding of the cultural ecology of the societies being studied, and of the limitations and opportunities that the environment (both natural and cultural) imposes on the evolution or devolution of human societies. Based on the assumption that cultures never develop in isolation, Anthropological Archaeology takes a regional approach to tackling fundamental issues concerning past cultural -

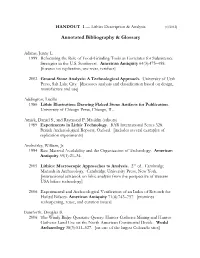

Lithic Analysis Bibliography & Glossary

HANDOUT 1 — Lithics Description & Analysis [4/2012] Annotated Bibliography & Glossary Adams, Jenny L. 1999 Refocusing the Role of Food-Grinding Tools as Correlates for Subsistence Strategies in the U.S. Southwest. American Antiquity 64(3):475–498. [focuses on replication, use wear, residues] 2002 Ground Stone Analysis: A Technological Approach. University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City. [discusses analysis and classification based on design, manufacture and use] Addington, Lucille 1986 Lithic Illustration: Drawing Flaked Stone Artifacts for Publication. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL. Amick, Daniel S., and Raymond P. Mauldin (editors) 1989 Experiments in Lithic Technology. BAR International Series 528. British Archaeological Reports, Oxford. [includes several examples of replication experiments] Andrefsky, William, Jr. 1994 Raw-Material Availability and the Organization of Technology. American Antiquity 59(1):21–34. 2005 Lithics: Macroscopic Approaches to Analysis. 2nd ed. Cambridge Manuals in Archaeology. Cambridge University Press, New York. [instructional textbook on lithic analysis from the perspective of western USA biface technology] 2006 Experimental and Archaeological Verification of an Index of Retouch for Hafted Bifaces. American Antiquity 71(4):743–757. [examines resharpening, reuse, and curation issues] Bamforth, Douglas B. 2006 The Windy Ridge Quartzite Quarry: Hunter-Gatherer Mining and Hunter- Gatherer Land Use on the North American Continental Divide. World Archaeology 38(3):511–527. [on one of the largest Colorado sites] Barnett, Franklin 1991 Dictionary of Prehistoric Indian Artifacts of the American Southwest. Northland Publishing Co., Flagstaff, AZ. Barton, C. Michael 1996 Beyond the Graver: Reconsidering Burin Function. Journal of Field Archaeology 23(1):111–125. [well-illustrated, but specific topic] Benedict, James B.