This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

15Th October at 19:00 Hours Or 7Pm AEST

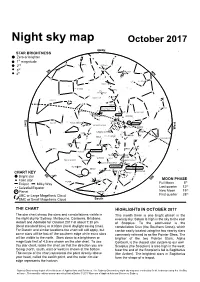

TheSky (c) Astronomy Software 1984-1998 TheSky (c) Astronomy Software 1984-1998 URSA MINOR CEPHEUS CASSIOPEIA DRACO Night sky map OctoberDRACO 2017 URSA MAJOR North North STAR BRIGHTNESS Zero or brighter 1st magnitude nd LACERTA Deneb 2 NE rd NE Vega CYGNUS CANES VENATICI LYRAANDROMEDA 3 Vega NW th NW 4 LYRA LEO MINOR CORONA BOREALIS HERCULES BOOTES CORONA BOREALIS HERCULES VULPECULA COMA BERENICES Arcturus PEGASUS SAGITTA DELPHINUS SAGITTA SERPENS LEO Altair EQUULEUS PISCES Regulus AQUILAVIRGO Altair OPHIUCHUS First Quarter Moon SERPENS on the 28th Spica AQUARIUS LIBRA Zubenelgenubi SCUTUM OPHIUCHUS CORVUS Teapot SEXTANS SERPENS CAPRICORNUS SERPENSCRATER AQUILA SCUTUM East East Antares SAGITTARIUS CETUS PISCIS AUSTRINUS P SATURN Centre of the Galaxy MICROSCOPIUM Centre of the Galaxy HYDRA West SCORPIUS West LUPUS SAGITTARIUS SCULPTOR CORONA AUSTRALIS Antares GRUS CENTAURUS LIBRA SCORPIUS NORMAINDUS TELESCOPIUM CORONA AUSTRALIS ANTLIA Zubenelgenubi ARA CIRCINUS Hadar Alpha Centauri PHOENIX Mimosa CRUX ARA CAPRICORNUS TRIANGULUM AUSTRALEPAVO PYXIS TELESCOPIUM NORMAVELALUPUS FORNAX TUCANA MUSCA 47 Tucanae MICROSCOPIUM Achernar APUS ERIDANUS PAVO SMC TRIANGULUM AUSTRALE CIRCINUS OCTANSCHAMAELEON APUS CARINA HOROLOGIUMINDUS HYDRUS Alpha Centauri OCTANS SouthSouth CelestialCelestial PolePole VOLANS Hadar PUPPIS RETICULUM POINTERS SOUTHERN CROSS PISCIS AUSTRINUS MENSA CHAMAELEONMENSA MUSCA CENTAURUS Adhara CANIS MAJOR CHART KEY LMC Mimosa SE GRUS DORADO SMC CAELUM LMCCRUX Canopus Bright star HYDRUS TUCANA SWSW MOON PHASE Faint star VOLANS DORADO -

AGM Minutes 2019 1 Minutes of The

Minutes of the 54th Annual General Meeting held at 1.30 pm (AEST)/1.00 pm (ACST)/11.30 pm (AWST) Wednesday 8 July 2020 Zoom online meeting The Meeting was opened at 1:30 am with the President in the Chair and approximately 110 members of all grades present in an entirely online meeting using Zoom. 1. Apologies Caroline Foster, Lisa Kewley 2. Minutes of the 53rd Annual General Meeting Motion that the minutes of the 54th Annual General Meeting be accepted. Couch/Lattanzio Carried 3. Business arising from the Minutes None. 4. President's Report The President, Cathryn Trott, presented a Powerpoint version of the official written report (below). 1. Council 2019-2020 Cathryn Trott President John Lattanzio Vice President Stuart Wyithe Immediate Past President John O’Byrne Secretary Marc Duldig Secretary Yeshe Fenner Treasurer Elisabete da Cunha Councillor Krzysztof Bolejko Councillor Ilya Mandel Councillor Barbara Catinella Councillor Daniel Zucker Councillor Christopher Matthew Student Representative Stas Shabala Chair, PASA Editorial Board (from January 2020) Tanya Hill (Co-opted) Prizes and Awards co-ordinator Michael Brown (Co-opted) Media and Outreach co-ordinator I would like to thank all council members for their contributions in the past year. Particular thanks go to council members holding ongoing roles in the society (John O’Byrne, Marc Duldig, Tanya Hill, and Michael Brown). Thanks go also to Gary Da Costa for continuing in his role as our “Public Officer”, and to Chapter Chairs Daniel Price, Mike Fitzgerald, Manodeep Sinha, Katie Jamieson and Dan Zucker. I would also like to acknowledge the work of Krzysztof Bolejko as Acting Prizes and Awards co-ordinator, while Tanya Hill is on leave. -

By Kathryn Sutherland

JANE AUSTEN’S DEALINGS WITH JOHN MURRAY AND HIS FIRM by kathryn sutherland Jane Austen had dealings with several publishers, eventually issuing her novels through two: Thomas Egerton and John Murray. For both, Austen may have been their first female novelist. This essay examines Austen-related materials in the John Murray Archive in the National Library of Scotland. It works in two directions: it considers references to Austen in the papers of John Murray II, finding some previously overlooked details; and it uses the example of Austen to draw out some implications of searching amongst the diverse papers of a publishing house for evidence of a relatively unknown (at the time) author. Together, the two approaches argue for the value of archival work in providing a fuller context of analysis. After an overview of Austen’s relations with Egerton and Murray, the essay takes the form of two case studies. The first traces a chance connection in the Murray papers between Austen’s fortunes and those of her Swiss contemporary, Germaine de Stae¨l. The second re-examines Austen’s move from Egerton to Murray, and the part played in this by William Gifford, editor of Murray’s Quarterly Review and his regular reader for the press. Although Murray made his offer for Emma in autumn 1815, letters in the archive show Gifford advising him on one, possibly two, of Austen’s novels a year earlier, in 1814. Together, these studies track early testimony to authorial esteem. The essay also attempts to draw out some methodological implications of archival work, among which are the broad informational parameters we need to set for the recovery of evidence. -

View Our Extensive Collection, and Allow Us to Assist You in Building Your Own Private Collection of Fine and Rare Books

We invite you to visit us at our new location in Palm Beach, Florida, view our extensive collection, and allow us to assist you in building your own private collection of fine and rare books. OUR GUARANTEE All items are fully guaranteed and can be returned within ten days. We accept all major credit cards and offer free domestic shipping and free worldwide shipping on orders over $500 for single item orders. A wide range of rushed shipping options are also available at cost. Each purchase is expertly packaged to ensure safe arrival and free gift wrapping services are available upon request. FOR THE COLLECTION OF A LIFETIME The process of creating one’s personal library is the pursuit of a lifetime. It requires special thought and consideration. Each book represents a piece of history, and it is a remarkable task to assemble these individual items into a collection. Our aim at Raptis Rare Books is to render tailored, individualized service to help you achieve your goals. We specialize in working with private collectors with a specific wish list, helping individuals find the ideal gift for special occasions, and partnering with representatives of institutions. We are here to assist you in your pursuit. Thank you for letting us be your guide in bringing the library of your imagination to reality. 561-508-3479 | 1-800-rare-book (1-800-727-3266) | [email protected] www.RaptisRareBooks.com 2 Contents Featured Antiquarian Books..................................................................4 Literature.............................................................................................12 -

L'institut Canadien De Montréal Et L'affaire Guibord

L'Institut Canadien de Montréal et l'Affaire Guibord Une page d'histoire par Le Père Théophile HUDON, s. j. MONTRÉAL Libroirie BEAUCHEMIN Limitée 430, rue Saint-Gabriel 1938 DU MÊME AUTEUR Historique de la Congrégation de Notre-Dame de Québec Québec, 1903. La Fédération des catholiques manitobaïns. Saint-Boniface, 1913. Le Conflit des races au foyer. Edmonton, 1917. L'école obligatoire. Québec, 1919. La Formation classique. — Nos vieux auteurs. Québec, 1921. Manuel de prononciation française. Montréal, 1931. L'obsession en politique. — L'esprit de parti. Montréal, 1935. Est-ce la fin de la Confédération? Montréal, 1936. L'Institut Canadien de Montréal «t l'Affaire Guibord 2VJIZ/ 0B8TAT, 19a maïi 1937. LÉON BOUVIER, s.j., Cens. dioc. IMPRIM1 POTEST, 25a junii 1937. E. PAPILLON, s.j., Provincial™. IMPRIMATUR, Marianopoliy Ida julii 1937. G.-H. CHARTIER, v. g. Imprimé tu Canada. — Printed in Canada. Droits réservés, Canada, 1938 — Copyright, U.S.A., 1938 par Librairie Beauchemin Limitée, Montréal. APPRÉCIATION Québec, le 20 mai 1937. Mon Bévérend Père, J'ai lu attentivement le manuscrit que vous m'avez laissé l'autre jour... J'ai trouvé le tout très bien et absolument irré prochable, je crois, au point de vue des faits historiques. Je dois vous dire que votre travail m'a fort intéressé. J'y ai vu des choses que je ne connaissais pas et en ai compris d'autres que je n'avais pu comprendre jusqu'à présent. Ce travail vaut certainement la peine d'être publié et sera utile à ceux qui veulent connaître l'histoire du fameux Institut Canadien de Montréal. -

Download Nightingale Fund Letters

Archives & Special Collections, Columbia University Health Sciences Library Auchincloss Florence Nightingale Collection AUCHINCLOSS, HUGH, 1878-1947, collector. FLORENCE NIGHTINGALE FUND LETTERS, 1848-1898 (bulk 1855-1856) 1 cubic foot (3 boxes) BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE: Hugh Auchincloss was born Dec. 28, 1878 in New York City. He was educated at Groton, was graduated from Yale in 1901, and received his medical degree from the College of Physicians and Surgeons (P&S), Columbia University, in 1905. After surgical residencies at Presbyterian and Roosevelt Hospitals in New York, he began a long association with both Presbyterian Hospital and P&S, eventually becoming Chief of the Second Surgical Division of Presbyterian and Professor of Clinical Surgery at P&S. He was best known for his skill in surgery of the hand and of the breast. He died in 1947. Florence Nightingale was born on May 12, 1820, in Florence, Italy to William Edward and Frances Smith Nightingale. Educated at home by her father, she later rejected the traditional role and pursuits of an upper-class Victorian lady to devote herself to nursing reform and public health advocacy. She became an iconic figure in Victorian Britain through her work nursing British troops during the Crimean War (1854-1856). Afterwards, though an invalid for most the rest of her life, Nightingale became an influential voice in government public health policy in late 19th century Britain, especially as it affected India. Nightingale died on August 13, 1910. HISTORICAL NOTE: The Florence Nightingale Fund was created as a result of the work of a group led by author Anna Maria Hall, her husband, journalist Samuel Carter Hall and statesman Sir Sidney Herbert and his wife, writer and prominent social figure Elizabeth Herbert, who in 1855 organized a public subscription to create a testament to Britain’s appreciation Florence Nightingale’s service to the nation during the Crimean War. -

A Nn Ual R Eport 20 17– 18

Powerhouse Museum Sydney Observatory Museums Discovery Centre Annual ReportAnnual 2017–18 The Hon Don Harwin MLC Leader of the Government in the Legislative Council Minister for Resources Minister for Energy and Utilities Minister for the Arts Vice President of the Executive Council Parliament House Sydney NSW 2000 Dear Minister On behalf of the Board of Trustees and in accordance with the Annual Reports (Statutory Bodies) Act 1984 and the Public Finance and Audit Act 1983, we submit for presentation to Parliament the Annual Report of the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences for the year ending 30 June 2018. Yours sincerely Professor Barney Glover FTSE FRSN Andrew Elliott President Acting Director ISSN: 2209-8836 © Trustees of the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences 2018 The Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences is an Executive Agency of, and principally funded by the NSW State Government. MAAS Annual Report 1 2017–18 Contents Acknowledgment of country .........................................................................2 Mission, Vision, Values ..................................................................................3 Strategic direction ........................................................................................ 4 President’s foreword ..................................................................................... 6 Director’s foreword ....................................................................................... 8 Future of MAAS ...........................................................................................10 -

'Discover' Issue 41 Pages 11-25 (PDF)

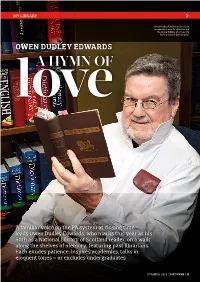

MY LIBRARY Owen Dudley Edwards’s father said he owed his career to a librarian and the former Edinburgh University history lecturer gets his point OWEN DUDLEY EDWARDS love A HYMN OF A familiar voice on the PA system at closing time leads Owen Dudley Edwards, who marks this year as his 50th as a National Library of Scotland reader, on a walk along the shelves of memory, featuring past librarians. Each exudes patience, inspires academics, talks in eloquent tones – or excludes undergraduates SUMMER 2019 | DISCOVER | 11 MY LIBRARY t is 6.40pm on Monday to Thursday, of authoritative Irish historiography or else 4.40pm on Friday or established in the academic journal Irish Saturday, and a voice is telling us to Historical Studies. Father was giving a draw our work to a conclusion. In 10 striking proof of what academics should minutes’ time it will tell us to finish know to be a truism, that behind every Iall work and hand in any of the property scholarly enterprise is one or more of the National Library of Scotland which librarians without whom it would have we may be using. been written on water. The Library is my home away from Richard Ellmann, master-biographer home, my best beloved public workplace of Joyce and Wilde, and David Krause, since I retired from lecturing in history at critic and editor of Sean O’Casey and his the University of Edinburgh 14 years ago, Letters, told me of their own debts to but cherished by me for a half-century. the National Library of Ireland. -

Preface and Acknowledgments

Preface and Acknowledgments This is a book about books— books of travel and of exploration that sought to describe, examine, and explain different parts of the world, between the late eighteenth century and the mid- nineteenth century. Our focus is on the works of non- European exploration and travel published by the house of Murray, Britain’s leading publisher of travel accounts and exploration nar- ratives in this period, between their fi rst venture in this respect, the 1773 publication of Sydney Parkinson’s A Journal of a Voyage to the South Seas, in His Majesty’s Ship, the Endeavour, and Leopold McClintock’s The Voyage of the ‘Fox’ in the Arctic Seas (1859), and with the activities of John Murray I (1737– 93), John Murray II (1778– 1843), and John Murray III (1808– 92) in turning authors’ words into print. This book is also about the world of bookmaking. Publishers such as Murray helped create interest in the world’s exploration and in travel writing by offering authors a route to social standing and sci- entifi c status— even, to a degree, literary celebrity. What is also true is that the several John Murrays and their editors, in working with their authors’ often hard- won words, commonly modifi ed the original accounts of explor- ers and travelers, partly for style, partly for content, partly to guard the reputation of author and of the publishing house, and always with an eye to the market. In a period in which European travelers and explorers turned their attention to the world beyond Europe and wrote works of lasting sig- nifi cance about their endeavors, what was printed and published was, of- ten, an altered and mediated version of the events of travel and exploration themselves. -

Contribution a L'histoire Intellectuelle De L'europe : Réseaux Du Livre

CONTRIBUTION A L’HISTOIRE INTELLECTUELLE DE L’EUROPE : RÉSEAUX DU LIVRE, RÉSEAUX DES LECTEURS Edité par Frédéric Barbier, István Monok L’Europe en réseaux Contribution à l’histoire de la culture écrite 1650–1918 Vernetztes Europa Beiträge zur Kulturgeschichte des Buchwesens 1650–1918 Edité par / Herausgegeben von Frédéric Barbier, Marie-Elisabeth Ducreux, Matthias Middell, István Monok, Éva Ring, Martin Svatoš Volume IV Ecole pratique des hautes études, Paris Ecole des hautes études en sciences sociales, Paris Centre des hautes études, Leipzig Centre européen d’histoire du livre de la Bibliothèque nationale Széchényi, Budapest CONTRIBUTION A L’HISTOIRE INTELLECTUELLE DE L’EUROPE : RÉSEAUX DU LIVRE, RÉSEAUX DES LECTEURS Edité par Frédéric Barbier, István Monok Országos Széchényi Könyvtár Budapest 2008 Les articles du présent volume correspondent aux Actes du colloque international organisé à Leipzig (Université de Leipzig, Zentrum für höhere Studien) en 2005, sur le thème « Netzwerke des Buchwesens : die Konstruktion Europas vom 15. bis zum 20. Jh. / Réseaux du livre, réseaux des lecteurs : la construction de l’Europe, XVe-XXe siècle ». Secrétariat scientifique Juliette Guilbaud (français) Wolfram Seidler (allemand) Graphiker György Fábián ISBN 978–963–200–550–8 ISBN 978–3–86583–269–6 © Országos Széchényi Könyvtár 1827 Budapest, Budavári palota F. épület Fax.: +36 1 37 56 167 [email protected] Leipziger Universitätsverlag GmbH, Leipzig Oststr. 41, D–04317 Leipzig Fax.: +49 341 99 00 440 [email protected] Table des matières Frédéric Barbier Avant-propos 7 Donatella Nebbiai Les réseaux de Matthias Corvin 17 Pierre Aquilon Précieux exemplaires Les éditions collectives des œuvres de Jean Gerson, 1483-1494 29 Juliette Guilbaud Das jansenistische Europa und das Buch im 17. -

Livres Et Société Bas-Canadienne, Croissance Et Expansion De La Librairie Fabre (1816-1855) Par Jean-Louis Roy *

Livres et société bas-canadienne, croissance et expansion de la librairie Fabre (1816-1855) par Jean-Louis Roy * 1 En France, grâce aux institutions et recherches de Lucien Febvre , 2 d'Henri-Jean Martin , de Robert Escarpit 3, de Jean Queniart 4, de Robert Mandrou 5 et d'autres, le livre est devenu objet de recherche historique, obli geant les chercheurs à superposer les dimensions économiques et sociales, intellectuelles et mentales qui surgissent de la richesse même de l'objet étudié, nommé «ferment:> par l'initiateur de l'apparition du livre. Au Québec, peu d'historiens du xix· siècle ont évité l'écueil de la géné ralisation, quant aux dimensions culturelles et intellectuelles de notre passé et quant aux relations qu'entretiennent jusqu'en 1855 les «Bas-Canadiens> et la France. Les recherches des professeurs Hare et Wallot sur les imprimés dans le Bas-Canada 6 , l'étude du professeur Galarneau, consacrée à la France devant l'opinion canadienne 7 (1760-1815) constituent, avec d'autres études, les premiers éléments d'un contrepoids essentiel. D'autres recherches effec 10 1 tuées par Dionne 8, Drolet 9 , Gagnon , Houle 1, s'ajoutent à ces ouvrages fondamentaux. Une mise à jour de notre histoire culturelle et intellectuelle, de son rythme, des liens qu'elle entretient avec les dynamiques extérieures, nous impose de retracer les objets culturels qui constituent le fondement des rela tions nées de ces objets. La recherche que nous présentoos aujourd'hui cons- titue une étape dans une étude d'ensemble. · * Centre d'études canadiennes-françaises, McGill University. 1 L. -

“The Other Woman” – Eliza Davis and Charles Dickens

44 DICKENS QUARTERLY “The Other Woman” – Eliza Davis and Charles Dickens MURRAY# BAUMGARTEN University of California, Santa Cruz he letters Eliza Davis wrote to Charles Dickens, from 22 June 1863 to 8 February 1867, and after his death to his daughter Mamie on 4 August 1870, reveal the increasing self-confidence of English Jews.1 TIn their careful and accurate comments on the power of Dickens’s work in shaping English culture and popular opinion, and their pointed discussion of the ways in which Fagin reinforces antisemitic English and European Jewish stereotypes, they indicate the concern, as Eliza Davis phrases it, of “a scattered nation” to participate fully in the life of “the land in which we have pitched our tents.2” It is worth noting that by 1858 the fits and starts of Jewish Emancipation in England had led, finally, to the seating of Lionel Rothschild in the House of Commons. After being elected for the fifth time from Westminster he was not required, due to a compromise devised by the Earl of Lucan and Benjamin Disraeli, to take the oath on the New Testament as a Christian.3 1 Research for this paper could not have been completed without the able and sustained help of Frank Gravier, Reference Librarian at the University of California, Santa Cruz, Assistant Librarian Laura McClanathan, Lee David Jaffe, Emeritus Librarian, and the detective work of David Paroissien, editor of Dickens Quarterly. I also want to thank Ainsley Henriques, archivist of the Kingston Jewish Community of Jamaica, Dana Evan Kaplan, the rabbi of the Kingston Jewish community, for their help, and the actress Miryam Margolyes for leading the way into genealogical inquiries.