The Jesuits and Globalization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

One Hundred Years of Thomism Aeterni Patris and Afterwards a Symposium

One Hundred Years of Thomism Aeterni Patris and Afterwards A Symposium Edited By Victor B. Brezik, C.S.B, CENTER FOR THOMISTIC STUDIES University of St. Thomas Houston, Texas 77006 ~ NIHIL OBSTAT: ReverendJamesK. Contents Farge, C.S.B. Censor Deputatus INTRODUCTION . 1 IMPRIMATUR: LOOKING AT THE PAST . 5 Most Reverend John L. Morkovsky, S.T.D. A Remembrance Of Pope Leo XIII: The Encyclical Aeterni Patris, Leonard E. Boyle,O.P. 7 Bishop of Galveston-Houston Commentary, James A. Weisheipl, O.P. ..23 January 6, 1981 The Legacy Of Etienne Gilson, Armand A. Maurer,C.S.B . .28 The Legacy Of Jacques Maritain, Christian Philosopher, First Printing: April 1981 Donald A. Gallagher. .45 LOOKING AT THE PRESENT. .61 Copyright©1981 by The Center For Thomistic Studies Reflections On Christian Philosophy, All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or Ralph McInerny . .63 reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written Thomism And Today's Crisis In Moral Values, Michael permission, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in Bertram Crowe . .74 critical articles and reviews. For information, write to The Transcendental Thomism, A Critical Assessment, Center For Thomistic Studies, 3812 Montrose Boulevard, Robert J. Henle, S.J. 90 Houston, Texas 77006. LOOKING AT THE FUTURE. .117 Library of Congress catalog card number: 80-70377 Can St. Thomas Speak To The Modem World?, Leo Sweeney, S.J. .119 The Future Of Thomistic Metaphysics, ISBN 0-9605456-0-3 Joseph Owens, C.Ss.R. .142 EPILOGUE. .163 The New Center And The Intellectualism Of St. Thomas, Printed in the United States of America Vernon J. -

New Books for December 2019 Grace, Predestination, and the Permission of Sin: a Thomistic Analysis by O'neill, Taylor Patrick, A

New Books for December 2019 Grace, predestination, and the permission of sin: a Thomistic analysis by O'Neill, Taylor Patrick, author. Book B765.T54 O56 2019 Faith and the founders of the American republic Book BL2525 .F325 2014 Moral combat: how sex divided American Christians and fractured American politics by Griffith, R. Marie 1967- author. (Ruth Marie), Book BR516 .G75 2017 Southern religion and Christian diversity in the twentieth century by Flynt, Wayne, 1940- author. Book BR535 .F59 2016 The story of Latino Protestants in the United States by Martínez, Juan Francisco, 1957- author. Book BR563.H57 M362 2018 The land of Israel in the Book of Ezekiel by Pikor, Wojciech, Book BS1199.L28 P55 2018 2 Kings by Park, Song-Mi Suzie, author. Book BS1335.53 .P37 2019 The Parables in Q by Roth, Dieter T., author. Book BS2555.52 .R68 2018 Hearing Revelation 1-3: listening with Greek rhetoric and culture by Neyrey, Jerome H., 1940- author. Book BS2825.52 .N495 2019 "Your God is a devouring fire": fire as a motif of divine presence and agency in the Hebrew Bible by Simone, Michael R., 1972- author. Book BS680.F53 S56 2019 Trinitarian and cosmotheandric vision by Panikkar, Raimon, Book BT111.3 .P36 2019 The life of Jesus: a graphic novel by Alex, Ben, author. Book BT302 .M66 2017 Our Lady of Guadalupe: the graphic novel by Muglia, Natalie, Book BT660.G8 M84 2018 An ecological theology of liberation: salvation and political ecology by Castillo, Daniel Patrick, author. Book BT83.57 .C365 2019 The Satan: how God's executioner became the enemy by Stokes, Ryan E., Book BT982 .S76 2019 Lectio Divina of the Gospels: for the liturgical year 2019-2020. -

Saint Ignatius Asks, "Are You Sure

Saint Ignatius Asks, "Are You Sure You Know Who I Am?" Joseph Veale, S.J. X3701 .S88* ONL PER tudies in the spirituality of Jesuits.. [St. Loui >sue: v.33:no.4(2001:Sept.) jrivalDate: 10/12/2001 Boston College Libraries 33/4 • SEPTEMBER 2001 THE SEMINAR ON JESUIT SPIRITUALITY The Seminar is composed of a number of Jesuits appointed from their provinces in the United States. It concerns itself with topics pertaining to the spiritual doctrine and prac- tice of Jesuits, especially United States Jesuits, and communicates the results to the members of the provinces through its publication, STUDIES IN THE SPIRITUALITY OF JESUITS. This is done in the spirit of Vatican II's recommendation that religious institutes recapture the original inspiration of their founders and adapt it to the circumstances of modern times. The Seminar welcomes reactions or comments in regard to the material that it publishes. The Seminar focuses its direct attention on the life and work of the Jesuits of the United States. The issues treated may be common also to Jesuits of other regions, to other priests, religious, and laity, to both men and women. Hence, the journal, while meant especially for American Jesuits, is not exclusively for them. Others who may find it helpful are cordially welcome to make use of it. CURRENT MEMBERS OF THE SEMINAR William A. Barry, S.J., directs the tertianship program and is a writer at Cam- pion Renewal Center, Weston, MA (1999). Robert L. Bireley, S.J., teaches history at Loyola University, Chicago, IL (2001) James F. Keenan, S.J., teaches moral theology at Weston Jesuit School of Theol- ogy, Cambridge, MA (2000). -

The Pre-History of Subsidiarity in Leo XIII

Journal of Catholic Legal Studies Volume 56 Number 1 Article 5 The Pre-History of Subsidiarity in Leo XIII Michael P. Moreland Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/jcls This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Catholic Legal Studies by an authorized editor of St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FINAL_MORELAND 8/14/2018 9:10 PM THE PRE-HISTORY OF SUBSIDIARITY IN LEO XIII MICHAEL P. MORELAND† Christian Legal Thought is a much-anticipated contribution from Patrick Brennan and William Brewbaker that brings the resources of the Christian intellectual tradition to bear on law and legal education. Among its many strengths, the book deftly combines Catholic and Protestant contributions and scholarly material with more widely accessible sources such as sermons and newspaper columns. But no project aiming at a crisp and manageably-sized presentation of Christianity’s contribution to law could hope to offer a comprehensive treatment of particular themes. And so, in this brief essay, I seek to elaborate upon the treatment of the principle of subsidiarity in Catholic social thought. Subsidiarity is mentioned a handful of times in Christian Legal Thought, most squarely with a lengthy quotation from Pius XI’s articulation of the principle in Quadragesimo Anno.1 In this proposed elaboration of subsidiarity, I wish to broaden the discussion of subsidiarity historically (back a few decades from Quadragesimo Anno to the pontificate of Leo XIII) and philosophically (most especially its relation to Leo XIII’s revival of Thomism).2 Statements of the principle have historically been terse and straightforward even if the application of subsidiarity to particular legal questions has not. -

Catholics, Slaveholders, and the Dilemma of American Evangelicalism, 1835–1860 / W

Catholics, Slaveholders, and the Dilemma of American Evangelicalism, 1835 –1860 W. J ASON WALLACE University of Notre Dame Press Notre Dame, Indiana © 2010 University of Notre Dame Press Copyright © 2010 by University of Notre Dame Notre Dame, Indiana 46556 www.undpress.nd.edu All Rights Reserved Manufactured in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Wallace, William Jason. Catholics, slaveholders, and the dilemma of American evangelicalism, 1835–1860 / W. Jason Wallace. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-268-04421-3 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-268-04421-X (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. United States—Church history—19th century. 2. Evangelicalism— United States—History—19th century. 3. Catholic Church— United States—History—19th century. 4. Slavery—United States— History—19th century. 5. Christianity and politics—United States— History—19th century. I. Title. BR525.W34 2010 282'.7509034—dc22 2010024340 ∞ The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. © 2010 University of Notre Dame Press Introduction Between 1835 and 1860, evangelical pulpits and religious journals in the North aggressively attacked slaveholders and Catholics as threats to American values. Criticisms of these two groups could often be found in the same northern evangelical journal, if not on the same page. Words such as “despotism” and “tyranny” described both the theological condi- tion of the Catholic Church and the political condition of the South. Slavery and Catholicism were labeled incompatible with republican insti- tutions and bereft of the virtues necessary to sustain a democratic people. -

Gen Assembly Report Extended V1

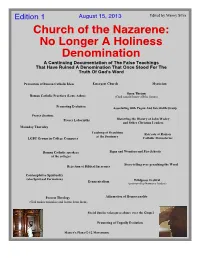

Edition 1 August 15, 2013 Edited by Manny Silva Church of the Nazarene: No Longer A Holiness Denomination A Continuing Documentation of The False Teachings That Have Ruined A Denomination That Once Stood For The Truth Of God's Word Promotion of Roman Catholic Ideas Emergent Church Mysticism Open Theism Roman Catholic Practices (Lent, Ashes) (God cannot know all the future) Promoting Evolution Associating with Pagan And Interfaith Group Prayer Stations Prayer Labyrinths Distorting the History of John Wesley and Other Christian Leaders Maunday Thursday Teaching of Occultism Retreats at Roman at the Seminary LGBT Groups in College Campuses Catholic Monasteries Roman Catholic speakers Signs and Wonders and Fire Schools at the colleges Story-telling over preaching the Word Rejection of Biblical Inerrancy Contemplative Spirituality (aka Spiritual Formation) Ecumenicalism Wildgoose Festival (promoted by Nazarene leaders) Process Theology Affirmation of Homosexuality (God makes mistakes and learns from them) Social Justice takes precedence over the Gospel Promoting of Ungodly Evolution Master's Plan (G-12 Movement) The Church of the Nazarene: General Assembly 2013 Report, And Various Papers Documenting The Heresies In The Church [This document can be copied and distributed to others to alert them to the state of the Church of the Nazarene and its universities and colleges. This document has been compiled for the sake of the brothers and sisters in Christ in the Church of the Nazarene. It is solely driven by love for those who may be, or have been, deceived by the many false teachings and teachers that have invaded the church. I cannot explain exactly why such blatantly unbiblical and satanic teachings have fooled so many. -

MID-TWENTIETH CENTURY NEO-THOMIST APPROACHES to MODERN PSYCHOLOGY Dissertation Submitted to the College of Arts and Sciences Of

MID-TWENTIETH CENTURY NEO-THOMIST APPROACHES TO MODERN PSYCHOLOGY Dissertation Submitted to The College of Arts and Sciences of the UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Theology By Matthew Glen Minix UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON Dayton, Ohio December 2016 MID-TWENTIETH CENTURY NEO-THOMIST APPROACHES TO MODERN PSYCHOLOGY Name: Minix, Matthew G. APPROVED BY: _____________________________________ Sandra A. Yocum, Ph.D. Dissertation Director _____________________________________ William L. Portier, Ph.D. Dissertation Reader. _____________________________________ Anthony Burke Smith, Ph.D. Dissertation Reader _____________________________________ John A. Inglis, Ph.D. Dissertation Reader _____________________________________ Jack J. Bauer, Ph.D. _____________________________________ Daniel Speed Thompson, Ph.D. Chair, Department of Religious Studies ii © Copyright by Matthew Glen Minix All rights reserved 2016 iii ABSTRACT MID-TWENTIETH CENTURY NEO-THOMIST APPROACHES TO MODERN PSYCHOLOGY Name: Minix, Matthew Glen University of Dayton Advisor: Dr. Sandra A. Yocum This dissertation considers a spectrum of five distinct approaches that mid-twentieth century neo-Thomist Catholic thinkers utilized when engaging with the tradition of modern scientific psychology: a critical approach, a reformulation approach, a synthetic approach, a particular [Jungian] approach, and a personalist approach. This work argues that mid-twentieth century neo-Thomists were essentially united in their concerns about the metaphysical principles of many modern psychologists as well as in their worries that these same modern psychologists had a tendency to overlook the transcendent dimension of human existence. This work shows that the first four neo-Thomist thinkers failed to bring the traditions of neo-Thomism and modern psychology together to the extent that they suggested purely theoretical ways of reconciling them. -

Europe (In Theory)

EUROPE (IN THEORY) ∫ 2007 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper $ Designed by C. H. Westmoreland Typeset in Minion with Univers display by Keystone Typesetting, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in- Publication Data appear on the last printed page of this book. There is a damaging and self-defeating assumption that theory is necessarily the elite language of the socially and culturally privileged. It is said that the place of the academic critic is inevitably within the Eurocentric archives of an imperialist or neo-colonial West. —HOMI K. BHABHA, The Location of Culture Contents Acknowledgments ix Introduction: A pigs Eye View of Europe 1 1 The Discovery of Europe: Some Critical Points 11 2 Montesquieu’s North and South: History as a Theory of Europe 52 3 Republics of Letters: What Is European Literature? 87 4 Mme de Staël to Hegel: The End of French Europe 134 5 Orientalism, Mediterranean Style: The Limits of History at the Margins of Europe 172 Notes 219 Works Cited 239 Index 267 Acknowledgments I want to thank for their suggestions, time, and support all the people who have heard, read, and commented on parts of this book: Albert Ascoli, David Bell, Joe Buttigieg, miriam cooke, Sergio Ferrarese, Ro- berto Ferrera, Mia Fuller, Edna Goldstaub, Margaret Greer, Michele Longino, Walter Mignolo, Marc Scachter, Helen Solterer, Barbara Spack- man, Philip Stewart, Carlotta Surini, Eric Zakim, and Robert Zimmer- man. Also invaluable has been the help o√ered by the Ethical Cosmopol- itanism group and the Franklin Humanities Seminar at Duke University; by the Program in Comparative Literature at Notre Dame; by the Khan Institute Colloquium at Smith College; by the Mediterranean Studies groups of both Duke and New York University; and by European studies and the Italian studies program at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. -

Download Article PDF , Format and Size of the File

History of humanitarian ideas The historical foundations of humanitarian action by Dr. Jean Guillermand After nearly 130 years of existence, the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement continues to play a unique and important role in the field of human relations. Its origin may be traced to the impression made on Henry Dunant, a chance witness at the scene, by the disastrous lack of medical care at the battle of Solferino in 1859 and the compassionate response aroused in the people of Lombardy by the plight of the wounded. The Movement has since gained importance and expanded to such a degree that it is now an irreplaceable institution made up of dedicated people all over the world. The Movement's success can clearly be attributed in great part to the commitment of those who carried on the pioneering work of its founders. But it is also the result of a constantly growing awareness of the conditions needed for such work to be accomplished. The initial text of the 1864 Convention was already quite explicit about its application in situations of armed conflict. Jean Pictet's analysis in 19S5 and the adoption by the Vienna Conference of the seven Fundamental Principles in 1965 have since codified in international law what was originally a generous and spontaneous impulse. In a world where the weight of hard-hitting arguments and the impact of the media play a key role in shaping public opinion, the fact that the Movement's initial spirit has survived intact and strong without having recourse to aggressive publicity campaigns or losing its independence to the political ideologies that divide the globe may well surprise an impartial observer of society today. -

Fiestas and Fervor: Religious Life and Catholic Enlightenment in the Diocese of Barcelona, 1766-1775

FIESTAS AND FERVOR: RELIGIOUS LIFE AND CATHOLIC ENLIGHTENMENT IN THE DIOCESE OF BARCELONA, 1766-1775 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Andrea J. Smidt, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2006 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Dale K. Van Kley, Adviser Professor N. Geoffrey Parker Professor Kenneth J. Andrien ____________________ Adviser History Graduate Program ABSTRACT The Enlightenment, or the "Age of Reason," had a profound impact on eighteenth-century Europe, especially on its religion, producing both outright atheism and powerful movements of religious reform within the Church. The former—culminating in the French Revolution—has attracted many scholars; the latter has been relatively neglected. By looking at "enlightened" attempts to reform popular religious practices in Spain, my project examines the religious fervor of people whose story usually escapes historical attention. "Fiestas and Fervor" reveals the capacity of the Enlightenment to reform the Catholicism of ordinary Spaniards, examining how enlightened or Reform Catholicism affected popular piety in the diocese of Barcelona. This study focuses on the efforts of an exceptional figure of Reform Catholicism and Enlightenment Spain—Josep Climent i Avinent, Bishop of Barcelona from 1766- 1775. The program of “Enlightenment” as sponsored by the Spanish monarchy was one that did not question the Catholic faith and that championed economic progress and the advancement of the sciences, primarily benefiting the elite of Spanish society. In this context, Climent is noteworthy not only because his idea of “Catholic Enlightenment” opposed that sponsored by the Spanish monarchy but also because his was one that implicitly condemned the present hierarchy of the Catholic Church and explicitly ii advocated popular enlightenment and the creation of a more independent “public sphere” in Spain by means of increased literacy and education of the masses. -

Religion and Civil Society in Massachusets: 1780-1833 Johann N

Western Washington University Western CEDAR History Faculty and Staff ubP lications History Fall 2004 The luE sive Common Good: Religion and Civil Society in Massachusets: 1780-1833 Johann N. Neem Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/history_facpubs Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Neem, Johann N., "The Elusive Common Good: Religion and Civil Society in Massachusets: 1780-1833" (2004). History Faculty and Staff Publications. 4. https://cedar.wwu.edu/history_facpubs/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Faculty and Staff Publications by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Elusive Common Good Religion and Civil Society in Massachusetts, 1780-1833 JOHANN N. NEEM In 1810, Theophilus Parsons, the Federalist chief justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Court, argued that the state need not recog- nize voluntary churches, calling the idea "too absurd to be admitted." In contrast, the modern idea of civil society is premised on the right of individual citizens to associate and for their institutions to gain the legal privileges connected with incorporation.' Federalists did not share this idea. They believed that in a republic the people's interests and the state's interests were the same, since voters elected their own rulers. JohannN. Neem, AssistantProfessor of History,Western Washington Univer- sity, is a postdoctoral fellow at the Center on Religion and Democracy at the University of Virginia. At Virginia, he thanks his adviser Peter S. -

Book Reviews ∵

journal of jesuit studies 4 (2017) 99-183 brill.com/jjs Book Reviews ∵ Thomas Banchoff and José Casanova, eds. The Jesuits and Globalization: Historical Legacies and Contemporary Challenges. Washington, dc: Georgetown University Press, 2016. Pp. viii + 299. Pb, $32.95. This volume of essays is the outcome of a three-year project hosted by the Berkley Center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs at Georgetown University which involved workshops held in Washington, Oxford, and Florence and cul- minated in a conference held in Rome (December 2014). The central question addressed by the participants was whether or not the Jesuit “way of proceeding […] hold[s] lessons for an increasingly multipolar and interconnected world” (vii). Although no fewer than seven out of the thirteen chapters were authored by Jesuits, the presence amongst them of such distinguished scholars as John O’Malley, M. Antoni Üçerler, Daniel Madigan, David Hollenbach, and Francis Clooney as well as of significant historians of the Society such as Aliocha Mal- davsky, John McGreevy, and Sabina Pavone together with that of the leading sociologist of religion, José Casanova, ensure that the outcome is more than the sum of its parts. Banchoff and Casanova make it clear at the outset: “We aim not to offer a global history of the Jesuits or a linear narrative of globaliza- tion but instead to examine the Jesuits through the prism of globalization and globalization through the prism of the Jesuits” (2). Accordingly, the volume is divided into two, more or less equal sections: “Historical Perspectives” and “Contemporary Challenges.” In his sparklingly incisive account of the first Jesuit encounters with Japan and China, M.