Why “Partitive Articles” Do Not Exist in (Old) Spanish

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 5 Variation in Romance Diego Pescarini and Michele Loporcaro

Variation in Romance Diego Pescarini, Michele Loporcaro To cite this version: Diego Pescarini, Michele Loporcaro. Variation in Romance. Cambridge Handbook of Romance Lin- guistics, In press. hal-02420353 HAL Id: hal-02420353 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02420353 Submitted on 19 Dec 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Chapter 5 Variation in Romance Diego Pescarini and Michele Loporcaro 5.1 Introduction This chapter sets out to show how the study of linguistic variation across closely related languages can fuel research questions and provide a fertile testbed for linguistic theory. We will present two case studies in structural variation – subject clitics and (perfective) auxiliation – and show how a comparative view of these phenomena is best suited to providing a satisfactory account for them, and how such a comparative account bears on a number of theoretical issues ranging from (rather trivially) the modeling of variation to the definition of wordhood, the inventory of parts of speech, and the division of labour between syntax and morphology. 5.2 Systematic variation: the case of subject clitics French, northern Italian Dialects, Ladin, and Romansh are characterized by the presence, with variable degrees of obligatoriness, of clitic elements stemming from Latin nominative personal pronouns. -

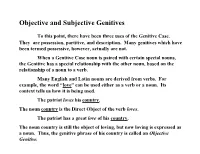

Objective and Subjective Genitives

Objective and Subjective Genitives To this point, there have been three uses of the Genitive Case. They are possession, partitive, and description. Many genitives which have been termed possessive, however, actually are not. When a Genitive Case noun is paired with certain special nouns, the Genitive has a special relationship with the other noun, based on the relationship of a noun to a verb. Many English and Latin nouns are derived from verbs. For example, the word “love” can be used either as a verb or a noun. Its context tells us how it is being used. The patriot loves his country. The noun country is the Direct Object of the verb loves. The patriot has a great love of his country. The noun country is still the object of loving, but now loving is expressed as a noun. Thus, the genitive phrase of his country is called an Objective Genitive. You have actually seen a number of Objective Genitives. Another common example is Rex causam itineris docuit. The king explained the cause of the journey (the thing that caused the journey). Because “cause” can be either a noun or a verb, when it is used as a noun its Direct Object must be expressed in the Genitive Case. A number of Latin adjectives also govern Objective Genitives. For example, Vir miser cupidus pecuniae est. A miser is desirous of money. Some special nouns and adjectives in Latin take Objective Genitives which are more difficult to see and to translate. The adjective peritus, -a, - um, meaning “skilled” or “experienced,” is one of these: Nautae sunt periti navium. -

Finnish Partitive Case As a Determiner Suffix

Finnish partitive case as a determiner suffix Problem: Finnish partitive case shows up on subject and object nouns, alternating with nominative and accusative respectively, where the interpretation involves indefiniteness or negation (Karlsson 1999). On these grounds some researchers have proposed that partitive is a structural case in Finnish (Vainikka 1993, Kiparsky 2001). A problematic consequence of this is that Finnish is assumed to have a structural case not found in other languages, losing the universal inventory of structural cases. I will propose an alternative, namely that partitive be analysed instead as a member of the Finnish determiner class. Data: There are three contexts in which the Finnish subject is in the partitive (alternating with the nominative in complementary contexts): (i) indefinite divisible non-count nouns (1), (ii) indefinite plural count nouns (2), (iii) where the existence of the argument is completely negated (3). The data are drawn from Karlsson (1999:82-5). (1) Divisible non-count nouns a. Partitive mass noun = indef b. c.f. Nominative mass noun = def Purki-ssa on leipä-ä. Leipä on purki-ssa. tin-INESS is bread-PART Bread is tin-INESS ‘There is some bread in the tin.’ ‘The bread is in the tin.’ (2) Plural count nouns a. Partitive count noun = indef b. c.f. Nominative count noun = def Kadu-lla on auto-j-a. Auto-t ovat kadulla. Street-ADESS is.3SG car-PL-PART Car-PL are.3PL street-ADESS ‘There are cars in the street.’ ‘The cars are in the street.’ (3) Negation a. Partitive, negation of existence b. c.f. -

AN INTRODUCTORY GRAMMAR of OLD ENGLISH Medieval and Renaissance Texts and Studies

AN INTRODUCTORY GRAMMAR OF OLD ENGLISH MEDievaL AND Renaissance Texts anD STUDies VOLUME 463 MRTS TEXTS FOR TEACHING VOLUme 8 An Introductory Grammar of Old English with an Anthology of Readings by R. D. Fulk Tempe, Arizona 2014 © Copyright 2020 R. D. Fulk This book was originally published in 2014 by the Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies at Arizona State University, Tempe Arizona. When the book went out of print, the press kindly allowed the copyright to revert to the author, so that this corrected reprint could be made freely available as an Open Access book. TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE viii ABBREVIATIONS ix WORKS CITED xi I. GRAMMAR INTRODUCTION (§§1–8) 3 CHAP. I (§§9–24) Phonology and Orthography 8 CHAP. II (§§25–31) Grammatical Gender • Case Functions • Masculine a-Stems • Anglo-Frisian Brightening and Restoration of a 16 CHAP. III (§§32–8) Neuter a-Stems • Uses of Demonstratives • Dual-Case Prepositions • Strong and Weak Verbs • First and Second Person Pronouns 21 CHAP. IV (§§39–45) ō-Stems • Third Person and Reflexive Pronouns • Verbal Rection • Subjunctive Mood 26 CHAP. V (§§46–53) Weak Nouns • Tense and Aspect • Forms of bēon 31 CHAP. VI (§§54–8) Strong and Weak Adjectives • Infinitives 35 CHAP. VII (§§59–66) Numerals • Demonstrative þēs • Breaking • Final Fricatives • Degemination • Impersonal Verbs 40 CHAP. VIII (§§67–72) West Germanic Consonant Gemination and Loss of j • wa-, wō-, ja-, and jō-Stem Nouns • Dipthongization by Initial Palatal Consonants 44 CHAP. IX (§§73–8) Proto-Germanic e before i and j • Front Mutation • hwā • Verb-Second Syntax 48 CHAP. -

Eslema. Towards a Corpus for Asturian

Eslema. Towards a Corpus for Asturian Xulio Viejoz, Roser Saur´ı∗, Angel´ Neiray zDepartamento de Filolog´ıa Espanola˜ yComputer Science Department Universidad de Oviedo fjviejo, [email protected] ∗Computer Science Department Brandeis University [email protected] Abstract We present Eslema, the first project devoted to building a corpus for Asturian, which is carried out at Oviedo University. Eslema receives minor funding from the Spanish government, which is fundamental for basic issues such as equipment acquisition. However, it is insufficient for hiring researchers for a reasonable period of time. The scarcity of funding prompted us to look for much needed resources in entities with no institutional relation to the project, such as publishing companies and radio stations. In addition, we have started collaborations with external research groups. We are for example initiating a project devoted to developing a wiki-based platform, to be used by the community of Asturian speakers, for loading and annotating texts in Eslema. That will benefit both our project, allowing to enlarge the corpus at a minimum cost, and the Asturian community, causing a stronger presence of Asturian in information technologies and, as a consequence, boosting the confidence of speakers in their language, which will hopefully contribute to slow down the serious process of substitution it is currently undergoing. 1. Introduction 1998. The most reliable estimates of the status and vitality We present Eslema, the first project devoted to building a of Asturian nowadays calculate the community of speak- corpus for Asturian, which is carried out by the Research ers corresponds to approximately a third of the population. -

The Handbook of Hispanic Linguistics

CMYK PMS 175mm 44.2mm 175mm José Ignacio Hualde is Professor in Hualde, The Handbook of the Department of Spanish, Italian, and Olarrea, and The Handbook of Hispanic Portuguese and in the Department of O’Rourke Linguistics at the University of Illinois at Linguistics Urbana-Champaign. His books include Basque Phonology (1991), Euskararen azentuerak Hispanic Edited by José Ignacio Hualde, Antxon Hispanic Linguistics Hispanic The Handbook of [the accentual systems of Basque] (1997), “The Handbook in its 40 well researched chapters presents a clear overview Olarrea and Erin O’Rourke and The Sounds of Spanish (2005). of different aspects of the Spanish language. As such it is destined to be an It is estimated that there are currently more important and indispensable reference resource which will be consulted for years Antxon Olarrea is Associate Professor in the Linguistics than 400 million Spanish speakers worldwide, to come.” with the United States being home to one of Department of Spanish and Portuguese at the Margarita Suñer, Cornell University the world’s largest native Spanish-speaking University of Arizona. He is author of Orígenes populations. Reflecting the increasing del lenguaje y selección natural (2005), “This handbook provides a comprehensive tour of the state-of-the art research importance of the Spanish language both coauthor of Introducción a la lingüística in all areas of Hispanic Linguistics. For students and scholars interested in the in the U.S. and abroad, The Handbook of hispánica (2001, 2nd ed. 2010), and coeditor Spanish language, it is a timely and invaluable reference book.” Hispanic Linguistics features a collection of Romance Linguistics (2009). -

A Corpus Study of Partitive Expression – Uncountable Noun Collocations

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Repository of Josip Juraj Strossmayer University of Osijek Sveučilište J. J. Strossmayerau Osijeku Filozofskifakultet Preddiplomski studij Engleskog jezika i književnosti i Pedagogije Anja Kolobarić A Corpus Study of Partitive Expression – Uncountable Noun Collocations Završni rad Mentor: izv. prof. dr. sc Gabrijela Buljan Osijek, 2014. Summary This research paper explores partitive expressions not only as devices that impose countable readings in uncountable nouns, but also as a means of directing the interpretive focus on different aspects of the uncountable entities denoted by nouns. This exploration was made possible through a close examination of specific grammar books, but also through a small-scale corpus study we have conducted. We first explain the theory behind uncountable nouns and partitive expressions, and then present the results of our corpus study, demonstrating thereby the creative nature of the English language. We also propose some cautious generalizations concerning the distribution of partitive expressions within the analyzed semantic domains. Key words: noncount noun, concrete noun, partitive expression, corpus data, data analysis 2 Contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................ 4 2. Theoretical Framework ........................................................................................... 5 2.1 Distinction between Count and Noncount -

The Semantics of Structural Case in Finnish

Absolutely a Matter of Degree: The Semantics of Structural Case in Finnish Paul Kiparsky CLS, April 2005 1. Functional categories (1) What are the functional categories of a language? A proposal. a. Syntax: functional categories are projected by functional heads. b. Morphology: functional categories are assigned by affixes or inherently marked on lexical items. c. Null elements may mark default values in paradigmatic system of functional categories. d. Otherwise functional categories are not specified. (2) a. Diachronic evidence: syntactic projections of functional categories emerge hand in hand with lexical heads (e.g. Kiparsky 1996, 1997 on English, Condoravdi and Kiparsky 2002, 2004 on Greek.) b. Empirical arguments from morphology (e.g. Kiparsky 2004). (3) Minimalist analysis of Accusative vs. Partitive case in Finnish (Borer 1998, 2005, Megerdoo- mian 2000, van Hout 2000, Ritter and Rosen 2000, Csirmaz 2002, Kratzer 2002, Svenonius 2002, Thomas 2003). a. Accusative is checked in AspP, a functional projection which induces telicity. b. Partitive is checked in a lower projection. • (1) rules out AspP for Finnish. (4) Position defended here (Kiparsky 1998): a. Accusative case is assigned to complements of BOUNDED (non-gradable) verbal pred- icates. b. Otherwise complements are assigned Partitive case. (5) Partitive case in Finnish: • a structural case (Vainikka 1993, Kiparsky 2001), • the default case of complements (Vainikka 1993, Anttila & Fong 2001), • syntactically alternates with Nominative, Genitive, and Accusative case. 1 • Following traditional grammar, we’ll treat Accusative as an abstract case that includes in addition to Accusative itself, the Accusative-like uses of Nominative and Genitive (for a different proposal, see Kiparsky 2001). -

Francisco Gago-Jover

FRANCISCO GAGO-JOVER PROFESSOR OF SPANISH 441 Stein Hall College of the Holy Cross Worcester, MA 01610 (508) 793-2507 [email protected] EDUCATION PhD (Hispano Romance Linguistics & Philology) University of Wisconsin-Madison 1990 - 1997 MA (Spanish) University of Wisconsin-Madison 1988 - 1990 Licenciado en Geografía e Historia Universidad de Valladolid 1980 - 1985 PUBLICATIONS A. BOOKS 2007: Diccionario militar de Raimundo Sanz. Edición y estudio. Zaragoza: Institución «Fernando el Católico». [co- edited with Fernando Tejedo-Herrero] 2002: Vocabulario militar castellano (siglos XIII-XV). Granada: Editorial Universidad de Granada. 2002: Two Generations: A Tribute to Lloyd A. Kasten (1905-1999). Ed. Francisco Gago-Jover. New York: Hispanic Seminary of Medieval Studies. 1999: Arte de bien morir y Breve confesionario. Palma de Mallorca: José Olañeta / Universitat de les Illes Balears. B. DIGITAL PROJECTS Forthcoming: Gago Jover, Francisco and F. Javier Pueyo Mena. 2020. Old Spanish Textual Archive. Hispanic Seminary of Medieval Studies. On line at http://www.oldspanishtextualarchive.org/osta/osta.php. 2018: “Colonial Texts”. Digital Library of Old Spanish Texts. Eds. Francisco Gago-Jover. Hispanic Seminary of Medieval Studies. http://www.hispanicseminary.org/t&c/col/index.htm 2017: “Fuero General de Navarra Texts”. Digital Library of Old Spanish Texts. Eds. Francisco Gago-Jover. Hispanic Seminary of Medieval Studies. http://www.hispanicseminary.org/t&c/fgn/index.htm 2017: “Lazarillo de Tormes (1554) Texts”. Digital Library of Old Spanish Texts. Eds. Francisco Gago-Jover. Hispanic Seminary of Medieval Studies. http://www.hispanicseminary.org/t&c/laz/index.htm 2016: “Spanish Chronicle Texts”. Digital Library of Old Spanish Texts. Eds. Francisco Gago-Jover. -

GRS LX 700 Language Acquisition and Linguistic Theory Parameters

GRS LX 700 Parameters Language Acquisition and • Languages differ in the settings of parameters (as Linguistic Theory well as in the pronunciations of the words, etc.). • To learn a second language is to learn the parameter settings for that language. • Where do you keep the parameters from the Week 10. second, third, etc. language? You don’t have a Parameters, transfer, and functional single parameter set two different ways, do you? categories in L2A • “Parameter resetting” doesn’t mean monkeying with your L1 parameter settings, it means setting your L2 parameter to its appropriate setting. Four views on the role of L1 Some parameters that have been parameters looked at in L2A • UG is still around to constrain L2/IL, parameter • Pro drop (null subject) parameter (whether empty settings of L1 are adopted at first, then parameters subjects are allowed; Spanish yes, English no) are reset to match L2. • Head parameter (where the head is in X-bar • UG does not constrain L2/IL but L1 does, L2 can structure with respect to its complement; Japanese adopt properties of L1 but can’t reset the head-final, English head-initial) parameters (except perhaps in the face of brutally • ECP/that-trace effect (*Who did you say that t left? direct evidence, e.g., headedness). English: yes, Dutch: no). • IL cannot be described in terms of parameter • Subjacency/bounding nodes (English: DP and IP, settings—it is not UG-constrained. Italian/French: DP and CP). • UG works the same in L1A and L2A. L1 shouldn’t have any effect. Null subject parameter Null subject parameter • The best parameters are those which have several • Spanish (+NS) L1 learning English (–NS) different effects. -

New Latin Grammar

NEW LATIN GRAMMAR BY CHARLES E. BENNETT Goldwin Smith Professor of Latin in Cornell University Quicquid praecipies, esto brevis, ut cito dicta Percipiant animi dociles teneantque fideles: Omne supervacuum pleno de pectore manat. —HORACE, Ars Poetica. COPYRIGHT, 1895; 1908; 1918 BY CHARLES E. BENNETT PREFACE. The present work is a revision of that published in 1908. No radical alterations have been introduced, although a number of minor changes will be noted. I have added an Introduction on the origin and development of the Latin language, which it is hoped will prove interesting and instructive to the more ambitious pupil. At the end of the book will be found an Index to the Sources of the Illustrative Examples cited in the Syntax. C.E.B. ITHACA, NEW YORK, May 4, 1918 PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION. The present book is a revision of my Latin Grammar originally published in 1895. Wherever greater accuracy or precision of statement seemed possible, I have endeavored to secure this. The rules for syllable division have been changed and made to conform to the prevailing practice of the Romans themselves. In the Perfect Subjunctive Active, the endings -īs, -īmus, -ītis are now marked long. The theory of vowel length before the suffixes -gnus, -gna, -gnum, and also before j, has been discarded. In the Syntax I have recognized a special category of Ablative of Association, and have abandoned the original doctrine as to the force of tenses in the Prohibitive. Apart from the foregoing, only minor and unessential modifications have been introduced. In its main lines the work remains unchanged. -

On Uses of the Finnish Partitive Subject in Transitive Clauses Tuomas Huumo University of Turku, University of Tartu

Chapter 15 The partitive A: On uses of the Finnish partitive subject in transitive clauses Tuomas Huumo University of Turku, University of Tartu Finnish existential clauses are known for the case marking of their S arguments, which alternates between the nominative and the partitive. Existential S arguments introduce a discourse-new referent, and, if headed by a mass noun or a plural form, are marked with the partitive case that indicates non-exhaustive quantification (as in ‘There is some coffee inthe cup’). In the literature it has often been observed that the partitive is occasionally used even in transitive clauses to mark the A argument. In this work I analyze a hand-picked set of examples to explore this partitive A. I argue that the partitive A phrase often has an animate referent; that it is most felicitous in low-transitivity expressions where the O argument is likewise in the partitive (to indicate non-culminating aspect); that a partitive A phrase typically follows the verb, is in the plural and is typically modified by a quantifier (‘many’, ‘a lot of’). I then argue that the pervasiveness of quantifying expressions in partitive A phrases reflects a structural analogy with (pseudo)partitive constructions where a nominative head is followed by a partitive modifier (e.g. ‘a group of students’). Such analogies may be relevant in permitting the A function to be fulfilled by many kinds of quantifier + partitiveNPs. 1 Introduction The Finnish argument marking system is known for its extensive case alternation that concerns the marking of S (single arguments of intransitive predications) and O (object) arguments, as well as predicate adjectives.