PATTERNS in POLYHEDRONS Stage 1 You Can Think of A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volumes of Prisms and Cylinders 625

11-4 11-4 Volumes of Prisms and 11-4 Cylinders 1. Plan Objectives What You’ll Learn Check Skills You’ll Need GO for Help Lessons 1-9 and 10-1 1 To find the volume of a prism 2 To find the volume of • To find the volume of a Find the area of each figure. For answers that are not whole numbers, round to prism a cylinder the nearest tenth. • To find the volume of a 2 Examples cylinder 1. a square with side length 7 cm 49 cm 1 Finding Volume of a 2. a circle with diameter 15 in. 176.7 in.2 . And Why Rectangular Prism 3. a circle with radius 10 mm 314.2 mm2 2 Finding Volume of a To estimate the volume of a 4. a rectangle with length 3 ft and width 1 ft 3 ft2 Triangular Prism backpack, as in Example 4 2 3 Finding Volume of a Cylinder 5. a rectangle with base 14 in. and height 11 in. 154 in. 4 Finding Volume of a 6. a triangle with base 11 cm and height 5 cm 27.5 cm2 Composite Figure 7. an equilateral triangle that is 8 in. on each side 27.7 in.2 New Vocabulary • volume • composite space figure Math Background Integral calculus considers the area under a curve, which leads to computation of volumes of 1 Finding Volume of a Prism solids of revolution. Cavalieri’s Principle is a forerunner of ideas formalized by Newton and Leibniz in calculus. Hands-On Activity: Finding Volume Explore the volume of a prism with unit cubes. -

Equivelar Octahedron of Genus 3 in 3-Space

Equivelar octahedron of genus 3 in 3-space Ruslan Mizhaev ([email protected]) Apr. 2020 ABSTRACT . Building up a toroidal polyhedron of genus 3, consisting of 8 nine-sided faces, is given. From the point of view of topology, a polyhedron can be considered as an embedding of a cubic graph with 24 vertices and 36 edges in a surface of genus 3. This polyhedron is a contender for the maximal genus among octahedrons in 3-space. 1. Introduction This solution can be attributed to the problem of determining the maximal genus of polyhedra with the number of faces - . As is known, at least 7 faces are required for a polyhedron of genus = 1 . For cases ≥ 8 , there are currently few examples. If all faces of the toroidal polyhedron are – gons and all vertices are q-valence ( ≥ 3), such polyhedral are called either locally regular or simply equivelar [1]. The characteristics of polyhedra are abbreviated as , ; [1]. 2. Polyhedron {9, 3; 3} V1. The paper considers building up a polyhedron 9, 3; 3 in 3-space. The faces of a polyhedron are non- convex flat 9-gons without self-intersections. The polyhedron is symmetric when rotated through 1804 around the axis (Fig. 3). One of the features of this polyhedron is that any face has two pairs with which it borders two edges. The polyhedron also has a ratio of angles and faces - = − 1. To describe polyhedra with similar characteristics ( = − 1) we use the Euler formula − + = = 2 − 2, where is the Euler characteristic. Since = 3, the equality 3 = 2 holds true. -

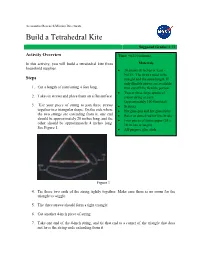

Build a Tetrahedral Kite

Aeronautics Research Mission Directorate Build a Tetrahedral Kite Suggested Grades: 8-12 Activity Overview Time: 90-120 minutes In this activity, you will build a tetrahedral kite from Materials household supplies. • 24 straws (8 inches or less) - NOTE: The straws need to be Steps straight and the same length. If only flexible straws are available, 1. Cut a length of yarn/string 4 feet long. then cut off the flexible portion. • Two or three large spools of 2. Take six straws and place them on a flat surface. cotton string or yarn (approximately 100 feet total) 3. Use your piece of string to join three straws • Scissors together in a triangular shape. On the side where • Hot glue gun and hot glue sticks the two strings are extending from it, one end • Ruler or dowel rod for kite bridle should be approximately 20 inches long, and the • Four pieces of tissue paper (24 x other should be approximately 4 inches long. 18 inches or larger) See Figure 1. • All-purpose glue stick Figure 1 4. Tie these two ends of the string tightly together. Make sure there is no room for the triangle to wiggle. 5. The three straws should form a tight triangle. 6. Cut another 4-inch piece of string. 7. Take one end of the 4-inch string, and tie that end to a corner of the triangle that does not have the string ends extending from it. Figure 2. 8. Add two more straws onto the longest piece of string. 9. Next, take the string that holds the two additional straws and tie it to the end of one of the 4-inch strings to make another tight triangle. -

THE GEOMETRY of PYRAMIDS One of the More Interesting Solid

THE GEOMETRY OF PYRAMIDS One of the more interesting solid structures which has fascinated individuals for thousands of years going all the way back to the ancient Egyptians is the pyramid. It is a structure in which one takes a closed curve in the x-y plane and connects straight lines between every point on this curve and a fixed point P above the centroid of the curve. Classical pyramids such as the structures at Giza have square bases and lateral sides close in form to equilateral triangles. When the closed curve becomes a circle one obtains a cone and this cone becomes a cylindrical rod when point P is moved to infinity. It is our purpose here to discuss the properties of all N sided pyramids including their volume and surface area using only elementary calculus and geometry. Our starting point will be the following sketch- The base represents a regular N sided polygon with side length ‘a’ . The angle between neighboring radial lines r (shown in red) connecting the polygon vertices with its centroid is θ=2π/N. From this it follows, by the law of cosines, that the length r=a/sqrt[2(1- cos(θ))] . The area of the iscosolis triangle of sides r-a-r is- a a 2 a 2 1 cos( ) A r 2 T 2 4 4 (1 cos( ) From this we have that the area of the N sided polygon and hence the pyramid base will be- 2 2 1 cos( ) Na A N base 2 4 1 cos( ) N 2 It readily follows from this result that a square base N=4 has area Abase=a and a hexagon 2 base N=6 yields Abase= 3sqrt(3)a /2. -

1 Lifts of Polytopes

Lecture 5: Lifts of polytopes and non-negative rank CSE 599S: Entropy optimality, Winter 2016 Instructor: James R. Lee Last updated: January 24, 2016 1 Lifts of polytopes 1.1 Polytopes and inequalities Recall that the convex hull of a subset X n is defined by ⊆ conv X λx + 1 λ x0 : x; x0 X; λ 0; 1 : ( ) f ( − ) 2 2 [ ]g A d-dimensional convex polytope P d is the convex hull of a finite set of points in d: ⊆ P conv x1;:::; xk (f g) d for some x1;:::; xk . 2 Every polytope has a dual representation: It is a closed and bounded set defined by a family of linear inequalities P x d : Ax 6 b f 2 g for some matrix A m d. 2 × Let us define a measure of complexity for P: Define γ P to be the smallest number m such that for some C s d ; y s ; A m d ; b m, we have ( ) 2 × 2 2 × 2 P x d : Cx y and Ax 6 b : f 2 g In other words, this is the minimum number of inequalities needed to describe P. If P is full- dimensional, then this is precisely the number of facets of P (a facet is a maximal proper face of P). Thinking of γ P as a measure of complexity makes sense from the point of view of optimization: Interior point( methods) can efficiently optimize linear functions over P (to arbitrary accuracy) in time that is polynomial in γ P . ( ) 1.2 Lifts of polytopes Many simple polytopes require a large number of inequalities to describe. -

Geometry © 2000 Springer-Verlag New York Inc

Discrete Comput Geom OF1–OF15 (2000) Discrete & Computational DOI: 10.1007/s004540010046 Geometry © 2000 Springer-Verlag New York Inc. Convex and Linear Orientations of Polytopal Graphs J. Mihalisin and V. Klee Department of Mathematics, University of Washington, Box 354350, Seattle, WA 98195-4350, USA {mihalisi,klee}@math.washington.edu Abstract. This paper examines directed graphs related to convex polytopes. For each fixed d-polytope and any acyclic orientation of its graph, we prove there exist both convex and concave functions that induce the given orientation. For each combinatorial class of 3-polytopes, we provide a good characterization of the orientations that are induced by an affine function acting on some member of the class. Introduction A graph is d-polytopal if it is isomorphic to the graph G(P) formed by the vertices and edges of some (convex) d-polytope P. As the term is used here, a digraph is d-polytopal if it is isomorphic to a digraph that results when the graph G(P) of some d-polytope P is oriented by means of some affine function on P. 3-Polytopes and their graphs have been objects of research since the time of Euler. The most important result concerning 3-polytopal graphs is the theorem of Steinitz [SR], [Gr1], asserting that a graph is 3-polytopal if and only if it is planar and 3-connected. Also important is the related fact that the combinatorial type (i.e., the entire face-lattice) of a 3-polytope P is determined by the graph G(P). Steinitz’s theorem has been very useful in studying the combinatorial structure of 3-polytopes because it makes it easy to recognize the 3-polytopality of a graph and to construct graphs that represent 3-polytopes without producing an explicit geometric realization. -

Name Date Period 1

NAME DATE PERIOD Unit 1, Lesson 13: Polyhedra Let’s investigate polyhedra. 13.1: What are Polyhedra? Here are pictures that represent polyhedra: Here are pictures that do not represent polyhedra: 1. Your teacher will give you some figures or objects. Sort them into polyhedra and non- polyhedra. 2. What features helped you distinguish the polyhedra from the other figures? 13.2: Prisms and Pyramids 1. Here are some polyhedra called prisms. 1 NAME DATE PERIOD Here are some polyhedra called pyramids. a. Look at the prisms. What are their characteristics or features? b. Look at the pyramids. What are their characteristics or features? 2 NAME DATE PERIOD 2. Which of the following nets can be folded into Pyramid P? Select all that apply. 3. Your teacher will give your group a set of polygons and assign a polyhedron. a. Decide which polygons are needed to compose your assigned polyhedron. List the polygons and how many of each are needed. b. Arrange the cut-outs into a net that, if taped and folded, can be assembled into the polyhedron. Sketch the net. If possible, find more than one way to arrange the polygons (show a different net for the same polyhedron). Are you ready for more? What is the smallest number of faces a polyhedron can possibly have? Explain how you know. 13.3: Assembling Polyhedra 1. Your teacher will give you the net of a polyhedron. Cut out the net, and fold it along the edges to assemble a polyhedron. Tape or glue the flaps so that there are no unjoined edges. -

Archimedean Solids

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln MAT Exam Expository Papers Math in the Middle Institute Partnership 7-2008 Archimedean Solids Anna Anderson University of Nebraska-Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/mathmidexppap Part of the Science and Mathematics Education Commons Anderson, Anna, "Archimedean Solids" (2008). MAT Exam Expository Papers. 4. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/mathmidexppap/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Math in the Middle Institute Partnership at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in MAT Exam Expository Papers by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Archimedean Solids Anna Anderson In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts in Teaching with a Specialization in the Teaching of Middle Level Mathematics in the Department of Mathematics. Jim Lewis, Advisor July 2008 2 Archimedean Solids A polygon is a simple, closed, planar figure with sides formed by joining line segments, where each line segment intersects exactly two others. If all of the sides have the same length and all of the angles are congruent, the polygon is called regular. The sum of the angles of a regular polygon with n sides, where n is 3 or more, is 180° x (n – 2) degrees. If a regular polygon were connected with other regular polygons in three dimensional space, a polyhedron could be created. In geometry, a polyhedron is a three- dimensional solid which consists of a collection of polygons joined at their edges. The word polyhedron is derived from the Greek word poly (many) and the Indo-European term hedron (seat). -

Shape Skeletons Creating Polyhedra with Straws

Shape Skeletons Creating Polyhedra with Straws Topics: 3-Dimensional Shapes, Regular Solids, Geometry Materials List Drinking straws or stir straws, cut in Use simple materials to investigate regular or advanced 3-dimensional shapes. half Fun to create, these shapes make wonderful showpieces and learning tools! Paperclips to use with the drinking Assembly straws or chenille 1. Choose which shape to construct. Note: the 4-sided tetrahedron, 8-sided stems to use with octahedron, and 20-sided icosahedron have triangular faces and will form sturdier the stir straws skeletal shapes. The 6-sided cube with square faces and the 12-sided Scissors dodecahedron with pentagonal faces will be less sturdy. See the Taking it Appropriate tool for Further section. cutting the wire in the chenille stems, Platonic Solids if used This activity can be used to teach: Common Core Math Tetrahedron Cube Octahedron Dodecahedron Icosahedron Standards: Angles and volume Polyhedron Faces Shape of Face Edges Vertices and measurement Tetrahedron 4 Triangles 6 4 (Measurement & Cube 6 Squares 12 8 Data, Grade 4, 5, 6, & Octahedron 8 Triangles 12 6 7; Grade 5, 3, 4, & 5) Dodecahedron 12 Pentagons 30 20 2-Dimensional and 3- Dimensional Shapes Icosahedron 20 Triangles 30 12 (Geometry, Grades 2- 12) 2. Use the table and images above to construct the selected shape by creating one or Problem Solving and more face shapes and then add straws or join shapes at each of the vertices: Reasoning a. For drinking straws and paperclips: Bend the (Mathematical paperclips so that the 2 loops form a “V” or “L” Practices Grades 2- shape as needed, widen the narrower loop and insert 12) one loop into the end of one straw half, and the other loop into another straw half. -

Systematics of Atomic Orbital Hybridization of Coordination Polyhedra: Role of F Orbitals

molecules Article Systematics of Atomic Orbital Hybridization of Coordination Polyhedra: Role of f Orbitals R. Bruce King Department of Chemistry, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602, USA; [email protected] Academic Editor: Vito Lippolis Received: 4 June 2020; Accepted: 29 June 2020; Published: 8 July 2020 Abstract: The combination of atomic orbitals to form hybrid orbitals of special symmetries can be related to the individual orbital polynomials. Using this approach, 8-orbital cubic hybridization can be shown to be sp3d3f requiring an f orbital, and 12-orbital hexagonal prismatic hybridization can be shown to be sp3d5f2g requiring a g orbital. The twists to convert a cube to a square antiprism and a hexagonal prism to a hexagonal antiprism eliminate the need for the highest nodality orbitals in the resulting hybrids. A trigonal twist of an Oh octahedron into a D3h trigonal prism can involve a gradual change of the pair of d orbitals in the corresponding sp3d2 hybrids. A similar trigonal twist of an Oh cuboctahedron into a D3h anticuboctahedron can likewise involve a gradual change in the three f orbitals in the corresponding sp3d5f3 hybrids. Keywords: coordination polyhedra; hybridization; atomic orbitals; f-block elements 1. Introduction In a series of papers in the 1990s, the author focused on the most favorable coordination polyhedra for sp3dn hybrids, such as those found in transition metal complexes. Such studies included an investigation of distortions from ideal symmetries in relatively symmetrical systems with molecular orbital degeneracies [1] In the ensuing quarter century, interest in actinide chemistry has generated an increasing interest in the involvement of f orbitals in coordination chemistry [2–7]. -

Math 366 Lecture Notes Section 11.4 – Geometry in Three Dimensions

Section 11-4 Math 366 Lecture Notes Section 11.4 – Geometry in Three Dimensions Simple Closed Surfaces A simple closed surface has exactly one interior, no holes, and is hollow. A sphere is the set of all points at a given distance from a given point, the center . A sphere is a simple closed surface. A solid is a simple closed surface with all interior points. (see p. 726) A polyhedron is a simple closed surface made up of polygonal regions, or faces . The vertices of the polygonal regions are the vertices of the polyhedron, and the sides of each polygonal region are the edges of the polyhedron. (see p. 726-727) A prism is a polyhedron in which two congruent faces lie in parallel planes and the other faces are bounded by parallelograms. The parallel faces of a prism are the bases of the prism. A prism is usually names after its bases. The faces other than the bases are the lateral faces of a prism. A right prism is one in which the lateral faces are all bounded by rectangles. An oblique prism is one in which some of the lateral faces are not bounded by rectangles. To draw a prism: 1) Draw one of the bases. 2) Draw vertical segments of equal length from each vertex. 3) Connect the bottom endpoints to form the second base. Use dashed segments for edges that cannot be seen. A pyramid is a polyhedron determined by a polygon and a point not in the plane of the polygon. The pyramid consists of the triangular regions determined by the point and each pair of consecutive vertices of the polygon and the polygonal region determined by the polygon. -

10-4 Surface and Lateral Area of Prism and Cylinders.Pdf

Aim: How do we evaluate and solve problems involving surface area of prisms an cylinders? Objective: Learn and apply the formula for the surface area of a prism. Learn and apply the formula for the surface area of a cylinder. Vocabulary: lateral face, lateral edge, right prism, oblique prism, altitude, surface area, lateral surface, axis of a cylinder, right cylinder, oblique cylinder. Prisms and cylinders have 2 congruent parallel bases. A lateral face is not a base. The edges of the base are called base edges. A lateral edge is not an edge of a base. The lateral faces of a right prism are all rectangles. An oblique prism has at least one nonrectangular lateral face. An altitude of a prism or cylinder is a perpendicular segment joining the planes of the bases. The height of a three-dimensional figure is the length of an altitude. Surface area is the total area of all faces and curved surfaces of a three-dimensional figure. The lateral area of a prism is the sum of the areas of the lateral faces. Holt Geometry The net of a right prism can be drawn so that the lateral faces form a rectangle with the same height as the prism. The base of the rectangle is equal to the perimeter of the base of the prism. The surface area of a right rectangular prism with length ℓ, width w, and height h can be written as S = 2ℓw + 2wh + 2ℓh. The surface area formula is only true for right prisms. To find the surface area of an oblique prism, add the areas of the faces.