The Breakfast Book

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Read Book Chefs Guide to Herbs and Spices

CHEFS GUIDE TO HERBS AND SPICES: REFERENCE GUIDE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Inc. Barcharts | 4 pages | 23 Feb 2006 | Barcharts, Inc | 9781423201823 | English | Boca Raton, FL, United States Chefs Guide to Herbs and Spices: Reference Guide PDF Book I also love it with lentils and in my chicken salad with apples. Cinnamon is beloved in both sweet and savory dishes around the world and can be used whole as sticks or ground. Email Required. They do tend to go stale and are not as pure as fresh ones so make sure they are green and strongly aromatic when you crush them. Read more about garlic here. Ginger powder is the dried and ground root of the flowering tropical plant Zingiber officinale, and has a milder and slightly sweeter taste than that of fresh ginger root. I never use parsley in dried form. Shred it and add it to a white sauce with mustard. From European mountains , but also moorland and heaths. Shrimp Alfredo is exquisite — juicy shrimp in a cheese sauce serves with pasta. It is widely used in Indian cuisine and is woody and pungent. The results is a lovely, sweetly smoky and lightly spiced flavor often found in spicy sausages like chorizo or salami, and paella. They also last for a long time in the fridge. Anise is the dried seed of an aromatic flowering plant, Pimpinella anisum , in the Apiaceae family that is native to the Levant, or eastern Mediterranean region, and into Southwest Asia. Cinnamon has a subtle, sweet, and complex flavor with floral and clove notes. -

Ed 395 677 Title Institution Spons Agency Pub Date Note

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 395 677 PS 024 219 TITLE Good Nutrition Promotes Health: Guide for Parent Nutrition Education. INSTITUTION Administration for Children, Youth, and Families (DHHS), Washington, DC. Head Start Bureau.; American Home Economics Association, Washington, D.C.; Food and Consumer Service (DOA), Washington, DC. SPONS AGENCY Kraft General Foods Foundation, Glenview, IL. PUB DATE Oct 94 NOTE 143p.; Accompanying videotapo not available from ERIC. Spanish-Language calendar printed in many colors. PUL TYPE Guides Non-Classroom Use (055) Multilingual/Bilingual Materials (171) LANGUAGE English; Spanish EDRS PRICE MF01/PC06 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Cultural Relevance; Food Standards; Hispanic American Culture; *Hispanic Americans; Latin American Culture; *Latin Americans; *Mexican Americans; *Nutrition Instruction; Parent Education; Preschool Education; Puerto Rican CuLture; *Puerto Ricans; Spanish IDENTIFIERS American Home Economics Association; Head Start Program Performance Standards; *Project Head Start ABSTRACT The purpose of this manual is to guide users of the nutrition education project produced by Padres Hispanos en Accion por Una Sana Generacion (Hispanic Parents in Action for a Healthy Generation). The project provides nutrition education materials to trainers who provide nutrition counseling to parents of Head Start children. The project has two goals: (1) to provide culturally specific nutrition information to three Hispanic populations within Head Start including Mexican-Americans, Puerto Ricans, and Central Americans; and (2) to strengthen the nutrition education and parent involvement components of Head Start. The materials produced by the project include three Spanish-language nutrition education videos specific to the three target cultural groups. A Spanish-language calendar was also produced to aid in nutritious menu planning and includes nutrition tips for parents and recipes drawn from the targe: cultural groups. -

Letmsm^Mm* Ggsjkazssilgsi CALIFORNIA PANEL

lEtmsm^mm* ggsjKazsSilgSi CALIFORNIA PANEL AfcoHage o* C tffo tiia .-.vrrtDotS B^tha Nut Tiee Restaur nit Nlil lice. California Bird Valley Quail Motto Eureka Goddess. .Minetva J^iwer Goldan Poppy Flag Beat Flag Il<;f Sequoia Redwood insecl Doc-tac« Butterfly Statehood .. 1HN1 Capitol . f'.acrainantu Soio 1 Lovt1 V I.IU California '^^^^0mK-•AVjS&f^^h^fr Minima; . GilzZly'Bear ^s |f ^(^^S Colots Blue and Gold f^^^ Fith . Golden Iioul Sc ok fe * v^ill 1" Jfe, \JI! Bight flags over California -• i'< SSL ^^"'jflft Spam 'S4,' 18; I : 1 England '57$ • 1HI9 ^ MI BBBH^B ES^ fiiassiS 812 1841 ™—-^ \£jyjjjE Buenos A-m, 1818 fcrrpire of Mek 11 .i lftk!1 i3 BepuHic of M IWII 1WJ-46 Pepouii'. oi (', Wo Lmitcif Statu* H111 III I III '•^S&^PJ*- •**- SD -^Uuzc^v^ ^-f- «. 46: T~i-a—- rff ,UJ2 gfofl^ (yuw&/ t^UtO^ „ J \JL\\J W^vjrtoyw v $>$&./ "S-f - Kxt^r i^feu^J^r ^--t^ uk&^- fi^, ft^e^^. 0 ^zfertav-u VtM^ i\P*^^, J —' lU/Z?1^v<5~ T^ * l/t^" /^fW-M- 4- £n<^c£>w IM&S\A/P**WJ TVL^ . pa^^ 'WvUZ-^-4<L> '^UOv^Sl' ^ lt<S&- I tfr£Q. -Jiif, &**** SWM t^nJe^^-^oC- ^Wo'Vf^jfCrtT-^o cJv_S2-c*-^s- *Se -TcerKjed- OT^C/OJ*3W l^» ^V~J" °T d VI^-ZHAJ s\t5l. , — T3 H0T^* C iAi^vv^cw<\ t< >6 J*^ *^ lip 7 crr°> r*!) ^ j^sCsr^fA/- Ai^vv^H^f/ HU^^s^ \ o 0 ^ _ L/ ? ^ V**sJ \A^*V yr \s -^ \y——— jr~r •** 182 it Xeerzu tsUj^t/ lfcp*~-*s - urVo&2/ ^U^ */f 3t. -

Top Shelf International Holdings Ltd

Top Shelf International Holdings Ltd Principal Place of Business: 16-18 National Boulevard Campbellfield Victoria Australia 3061 22 July 2021 ASX ANNOUNCEMENT (ASX:TSI) Top Shelf International (“TSI”), Australia’s leading premium spirits company, provides an overview of its Maturing Spirit Inventory and Net Sales Value. As at 30 June 2021 • At 30 June 2021, TSI had maturing spirits (Whisky & Agave) with a Net Sales Value of $272 million, an increase of 521% YOY and 154% above Prospectus. • TSI’s total spirit inventory increased to 3.5 million litres in FY21, an increase of 410% on 30 June 2020. • In FY21 2H, TSI achieved an Average Net Sales Value per litre for NED Whisky of $71.40 (an increase of 23% from FY21 1H to FY21 2H). TSI engaged PwC to perform certain procedures on the calculations and methodology to derive the 30 June 2021 whisky Net Sales Value per litre calculation. Forecast • With planned production considered: • By 30 June 2022, TSI forecasts that Net Sales Value of maturing spirits will increase to $418 million. • TSI will have a total of 6.6 million litres of mature spirits (Whisky & Agave) available for sale within the next five years (prior to 30 June 2026) with a Net Sales Value of $500 million. • Net Sales Value over a five year period is an important metric for TSI. It provides an indication of timeframes in which inventory can be expected to be available for sale. The five year period corresponds with: • Two maturation cycles of Whisky, and; • One maturation cycle of Agave. Refer to TSI’s maturing spirit inventory presentation dated 22 July 2021. -

Therapeutic Effects of Bossenbergia Rotunda

International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) ISSN (Online): 2319-7064 Index Copernicus Value (2015): 78.96 | Impact Factor (2015): 6.391 Therapeutic Effects of Bossenbergia rotunda S. Aishwarya Bachelor of Dental Surgery, Saveetha Dental College and Hospitals Abstract: Boesenbergia rotunda (L.) (Fingerroot), formerly known as Boesenbergia or Kaempferiapandurata (Roxb). Schltr. (Zingiberaceae), is distributed in south-east Asian countries, such as Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand. The rhizomes of this plant have been used for the treatment of peptic ulcer, as well as colic, oral diseases, urinary disorders, dysentery and inflammation. As people have started to focus more on natural plants species for their curative properties. B. rotunda is a native ingredient in many Asian countries and is used as a condiment in food. It is also used as traditional medicine to treat several illnesses, consumed as traditional tonic especially after childbirth, beauty aid for teenage girls, and as a leukorrhea preventive remedy for women. Its fresh rhizomes are also used to treat inflammatory diseases, in addition to being used as an antifungal, antiparasitic, and aphrodisiac among Thai folks. Moreover, AIDS patients self-medicate themselves with B. rotunda to cure the infection. With the advancement in technology, the ethnomedicinal usages of herbal plants can be explained through in vitro and in vivo studies to prove the activities of the plant extracts. The current state of research on B. rotunda clearly shows that the isolated bioactive compounds have high potential in treating many diseases. Keywords: Zingerberaceae, anti fungal, anti parasitic, Chalcones, flavonoids. 1. Introduction panduratin derivative are prenylated flavonoids from B. pandurata that showed broad range of biological activities, Boesenbergia rotunda is a ginger species that grows in such as strong antibacterial acitivity9-11, anti- inflammatory Southeast Asia, India, Sri Lanka, and Southern China. -

Press Pack Bretagne

2021 PRESS PACK BRETAGNE brittanytourism.com | CONTENTS Editorial p. 03 Slow down Take your foot off the pedal p. 04 Live Experience the here and now p. 12 Meet Immerse yourself in local culture p. 18 Share Together. That’s all ! p. 24 Practical information p. 29 EDITORIAL Bon voyage 2020 has been an unsettling and air and the wide open spaces. Embracing with the unexpected. A concentration of challenging year and we know that many the sea. Enjoying time with loved ones. the essential, and that’s why we love it! It of you have had to postpone your trip to Trying something new. Giving meaning to invites you to slow down, to enjoy life, to Brittany. These unusual times have been our daily lives. Meeting passionate locals. meet and to share: it delivers its promise a true emotional rollercoaster. They Sharing moments and laughs. Creating of uniqueness. So set sail, go for it, relax have also sharpened our awareness and memories for the years to come. and enjoy it as it comes. Let the eyes do redesigned our desires. We’re holding on to Let’s go for an outing to the Breton the talking and design your next holiday our loved ones, and the positive thoughts peninsula. A close, reassuring destination using these pages. of a brighter future. We appreciate even just across the Channel that we think we We wish you a wonderful trip. more the simple good things in life and know, but one that takes us far away, on the importance of seizing the moment. -

Premium Prestige

Premium Prestige Dine Point Conversion for every SGD 1 10 points 15 points Point Redemption for every 100 points (1) SGD 1 SGD 1 Complimentary Bottle of Wine 12 adults and above 6 adults and above (Temporarily not available for Premium members) (Maximum 30 adults) (2) Complimentary Dim Sum Lunch at Hai Tien Lo (3) Complimentary Gift (Bottle of Champagne or Wine) (4) Personal Happy Hour at Atrium (5) Complimentary Parking (5) Complimentary Valet Parking Priority Table Reservation Participating Outlets Atrium 15% on total bill Complimentary Sausage or Cheese Platter with every SGD 100* spent Edge (6) 10% on total bill 15% on total bill Hai Tien Lo 15% on à la carte orders Keyaki 15% on à la carte orders Pacific Marketplace 15% on total bill Complimentary Lemongrass drink with every order of an Asian Delight Poolside Bar 15% on total bill 15% on total bill Occasion (Applicable within the calendar month) Birthday Treat (7) Cake or Chocolate Cake, Chocolate or Wine Birthday Bonus Points (7) 500 1,000 Birthday Meal (8) Wedding Anniversary Treat (7) Cake or Chocolate Cake, Chocolate or Wine Wedding Anniversary Bonus Points (7) 500 1,000 Exclusive Member Event Stay Complimentary Panoramic Room Stay (9) Room Rates Savings (10) 15% via link 20% via link Spa at St. Gregory (11) 10% 15% Some benefits may not be applicable during this period till further notice (1) Excluding eve of Public Holidays and Public Holidays, black-out dates apply. Not applicable for promotional and festive items unless otherwise stated. (2) Member only. Once per membership term, available from Monday to Friday. -

Soup & Salads Handhelds Appetizers Mains

Mains TENDERLOIN PASTA beef tenderloin tips, spaghetti, sauteed mushrooms, spinach, bourbon peppercorn cream, blue cheese crumbles 24 SOUP & SALADS MEATLOAF SANDWICH toasted sourdough, housemade beef gravy, CHICKEN CAESAR SALAD romaine, house caesar dressing, croutons, buttered peas, country fried onion 17 fresh grated pecorino romano cheese, cracked black pepper, grilled chicken breast 12 CHICKEN & BISCUITS stewed chicken, peas, carrots, homemade gravy, STEAK SALAD (GF) served over two buttermilk biscuits 14 spring mix, romaine, tomatoes, shaved red onion, steak, cheddar cheese, french fries 16 FISH N’ CHIPS beer battered, served with French fries + coleslaw 15 WEDGE (GF) 1/4 head of iceburg lettuce, peppered bacon, BLACKENED CHICKEN ALFREDO cherry tomatoes, bleu cheese dressing, chives 11 6 oz chicken breast, house blend blackening spice, black pepper alfredo, fettucine, parmesan 18 ROASTED BEET SALAD (GF) PORK CHEEK TACOS Arcadian greens, smoked blue cheese, red onion, braised pork cheeks, lettuce, pico de gallo, toasted almonds, shaved carrots, dried cranberries, cotija cheese, cilantro sour cream 16 balsamic vinaigrette 12 SOUP OF THE MOMENT 5 PAN SEARED SALMON sauteed broccolini, roasted red potatoes, dill cream 25 Appetizers NY STRIP STEAK (GF) FRIED CALAMARI 12 oz grilled strip steak, herbed garlic butter, jalapeños, sesame seeds, greens, scallions, mashed potatoes, house vegetables 28 teriyaki glaze, sriracha mayo 15 Handhelds CANDIED BOURBON BACON (GF) braised pork belly, sliced + candied, REUBEN barrel aged bourbon -

Botanics in a Bottle

Insider THIRST QUENCHER Botanics in a bottle Propelled by dynamic craft spirit makers and cutting-edge mixologists, the Australian gin scene is growing up AUSTRALIA IS IN THE MIDDLE of a gin renaissance. Driven by distilleries, boutique bars and mastermind mixologists, we are becoming more “gintrified” than ever. Our consumption of juniper juice is booming and our craft distilleries are collecting prestigious international awards. Te secret, it seems, is the Indigenous ingredients being used – native myrtle, Tasmanian pepperberry, finger limes and wattle seed – wielded with wizardry in sheds and wineries across the country. Andrew Marks of the Melbourne Gin Company makes gin at his parent’s winery, Gembrook Hill “Tere’s a strong appetite for ‘local’ Four Pillars’ Cameron McKenzie, Vineyard, in the Yarra Valley, 50 in a lot of facets of people’s lives; a winemaker, and others such as minutes from Melbourne. He takes a they’re trying to support farming and Sacha La Forgia of 78 Degrees in winemaking approach, distilling all producers and this is just another the Adelaide Hills have been drawn 11 botanicals separately – including avenue to do so,” says Andrew. to the craft by the opportunity to local grapefruit peel, macadamias Te West Winds Gin from Western experiment with botanicals and and sandalwood – to better gauge Australia and Victorian-based Four flavour. the effect each has on the finished Pillars have put Australian gin on Oddly though, the story of product. Tey’re then blended and the map. Four Pillars, also based in Australia’s craft gin craze actually cut back with filtered rainwater the Yarra Valley, scooped the San begins with whisky. -

Treball De Fi De Grau

Facultat de Ciències de la Comunicació Treball de fi de grau Títol Autor/a Tutor/a Grau Data Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona Facultat de Ciències de la Comunicació Full Resum del TFG Títol del Treball Fi de Grau: Autor/a: Tutor/a: Any: Titulació: Paraules clau (mínim 3) Català: Castellà: Anglès: Resum del Treball Fi de Grau (extensió màxima 100 paraules) Català: Castellà: Anglès Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona TRABAJO DE FIN DE GRADO Plan estratégico de lanzamiento y comunicación de la marca Milo, de Nestlé, en España. Autora: Paula Ariza Soisa Tutor: Dr. Mariano Castellblanque Ramiro Grado en Publicidad y Relaciones Públicas Facultad de Ciencias de la Comunicación Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona 1 de junio de 2018 TABLA DE CONTENIDO 1. INTRODUCCIÓN .................................................................................................................................. Pág.1 2. DESCRIPCIÓN DEL PROYECTO ............................................................................................................ Pág.2 2.1. Justificación ........................................................................................................................ Pág.2 2.2. Objetivos ........................................................................................................................... Pág.2 2.3. Metodología ....................................................................................................................... Pág.3 3. CONTEXTO GENERAL ....................................................................................................................... -

VG321 the Continuous Cooking of Onions for Food Processing and Food Service Application

VG321 The continuous cooking of onions for food processing and food service application Penny Hlavaty Food Design Pty Ltd VG321 This report is published by the Horticultural Research and Development Corporation to pass on information concerning horticultural research and development undertaken for the onion industry. The research contained in this report was funded by the Horticultural Research and Development Corporation with the financial support of the Masterfoods Australia Limited. All expressions of opinion are not to be regarded as expressing the opinion of the Horticultural Research and Development Corporation or any authority of the Australian Government. The Corporation and the Australian Government accept no responsibility for any of the opinions or the accuracy of the information contained in this Report and readers should rely upon their own inquiries in making decisions concerning their own interests. Cover Price $20.00 HRDC ISBN 1 86423 499 7 Published and Distributed by: Horticultural Research and Development Corporation Level 6 7 Merriwa Street Gordon NSW 2072 Telephone: (02) 9418 2200 Fax: (02) 9418 1352 © Copyright 1997 FINAL REPORT THE CONTINUOUS COOKING OF ONIONS FOR FOOD PROCESSING AND FOOD SERVICE APPLICATION PROJECT NO.VG321 HORTICULTURAL RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION MASTER FOODS OF AUSTRALIA PENNY HLAVATY Project Chief Investigator KAREN MURDEN Food Technology Gradeuate Assistant FOOD INDUSTRY DEVELOPMENT CENTRE Project Manager Table of Contents Executive Summary 1 1. Introduction 3 1.1 Literature Survey on Onions and Capsicum 4 2. Methodology 5 3. Onion Project Market Research Report 6 3.1 Methodology 3.2 Food Manufacture 3.3 Results for Manufacturers 8 3.4 The Food Service Industry 3.5 Response in the Food Service Sectors 9 3.6 Conclusion 11 4. -

Download the Result

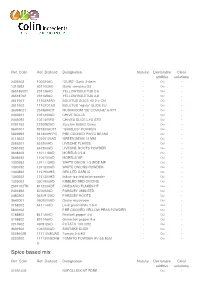

Ref. Colin Ref. Diafood Designation Natural Declarable Clear additive solutions 2408502 100024AD "OURS" Garlic 2-4mm - Oui - 1310592 5311G3AD Garlic semolina G3 - Oui - 36518502T 231126AD YELLOW BOLETUS 2-6 - Oui - 36518702 231169AD YELLOW BOLETUS 3-8 - Oui - 3611601 11102A2AD BOLETUS SLICE A2 2-4 CM - Oui - 3611602 11102O1AD BOLETUS "edulis" SLIDE EU - Oui - 3638902T 251969ADT MUSHROOM "DE COUCHE" 6-9TT - Oui - 2443201 1021400AD CHIVE ROLLS - Oui - 2445092 1021400FD CHIVES SLICE LYO STD - Oui - 0091162 1230982AD Zucchini 8X8X2 China - Oui - 3640101 921300ADTT "GIROLES" POWDER - Oui - 5823992 941300HFPC PRE COOKED PINTO BEANS - Oui - 0113602 10100125AD GREEN BEAN 12 MM - Oui - 2585201 651200AD LIVECHE FLAKES - Oui - 2585192 651300AD LIVECHE ROOTS POWDER - Oui - 3648403 1101118AD MORELS 0.5-8 - Oui - 3648492 1100700AD MORELS MP - Oui - 1330592 1241113AD WHITE ONION 1-3 INDE MP - Oui - 1330192 1241300AD WHITE ONIONS POWDER - Oui - 1340892 1151900HS GRILLED GARLIC - Oui - 1340202 1151300HS Indian toasted onion powder - Oui - 1326002 3501900AD KIBBLED RED ONIONS - Oui - 2591702TK 811200ADT OREGANO FLAKES HT - Oui - 2491892 870022AD PARSLEY 2MM STD - Oui - 2480902 3670912AD PARSLEY ROOTS - Oui - 3642001 0502000AD Oyster mushroom - Oui - 0158202 641114AD Leek green/white 1.5-4 - Oui - 5830102 PRE COOKED YELLOW PEAS POWDER - Oui - 0188802 841146AD Red bell pepper 4-6 - Oui - 0198802 831146AD Green bell pepper 4-6 - Oui - 0210902 490912AD POTATO 10X10X2 - Oui - 3692902 1040200AD SHIITAKE SLICE - Oui - 0228402E 1171124EUAD Tomato 2-4 EU - Oui - 0220202 1171300SDHB TOMATO POWDER HV SS E551 - Oui - O Spice based mix Ref. Colin Ref. Diafood Designation Natural Declarable Clear additive solutions 010A1402 NAPOLI MIX NF PDRE - Oui - Flavourings & Food Colourings Ref. Colin Ref. Diafood Designation Natural Declarable Clear additive solutions 284R17051 B SEASONING CURRY - - - 301U2001 LIME FLAVOUR NA Oui - - 600012102 Basil and tomato Edamame mix - Oui - Flavours Ref.