Intertwined Texts: Bible and Quran in Dialogue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mindfulness in the Life of a Muslim

2 | Mindfulness in the Life of a Muslim Author Biography Justin Parrott has BAs in Physics, English from Otterbein University, MLIS from Kent State University, MRes in Islamic Studies in progress from University of Wales, and is currently Research Librarian for Middle East Studies at NYU in Abu Dhabi. Disclaimer: The views, opinions, findings, and conclusions expressed in these papers and articles are strictly those of the authors. Furthermore, Yaqeen does not endorse any of the personal views of the authors on any platform. Our team is diverse on all fronts, allowing for constant, enriching dialogue that helps us produce high-quality research. Copyright © 2017. Yaqeen Institute for Islamic Research 3 | Mindfulness in the Life of a Muslim Introduction In the name of Allah, the Gracious, the Merciful Modern life involves a daily bustle of noise, distraction, and information overload. Our senses are constantly stimulated from every direction to the point that a simple moment of quiet stillness seems impossible for some of us. This continuous agitation hinders us from getting the most out of each moment, subtracting from the quality of our prayers and our ability to remember Allah. We all know that we need more presence in prayer, more control over our wandering minds and desires. But what exactly can we do achieve this? How can we become more mindful in all aspects of our lives, spiritual and temporal? That is where the practice of exercising mindfulness, in the Islamic context of muraqabah, can help train our minds to become more disciplined and can thereby enhance our regular worship and daily activities. -

RELI 3850: God in Israel: Historical Encounters NOTE THIS COURSE OUTLINE IS NOT FINAL UNTIL the FIRST DAY of CLASS

RELI 3850: God in Israel: Historical Encounters NOTE THIS COURSE OUTLINE IS NOT FINAL UNTIL THE FIRST DAY OF CLASS. The most up‐to‐date version of the syllabus is on CULearn CARLETON UNIVERSITY GOD IN ISRAEL: HISTORICAL ENCOUNTERS COLLEGE OF THE HUMANITIES RELI 3850: TOPICS IN STUDY OF RELIGION ABROAD RELIGION PROGRAM Israel: May 4‐27, 2014 Dr. Deidre Public course web site for info and uploading blogs [email protected] about the course www.carleton.ca/studyisrael Dr. Shawna Dolansky Official Course Facebook page: public fb page for [email protected] friends and families to see where we are going. Post photos, videos, tweet about the course. https://www.facebook.com/studyisraelwithZC CU Learn site for readings and grades Description: This third‐year travel course will survey religious history through geographical exploration of famous sites all over Israel: biblical Israel at the Temple Mount; origins of Christianity out of Judaism in the Galilee and in Jerusalem; Second Temple Judaism at Qumran and Masada; Rabbinic Judaism in ancient synagogues and in a special exhibit at the Israel Museum; the Crusades at the ruins of a Crusader fortress; Jewish mysticism in 17th century Safed; the Holocaust at Yad Vashem; modern Israel at the Knesset, a kibbutz, the Baha’i Temple in Haifa, and the beaches of Tel Aviv. Required Texts: Required readings This travel course includes travel in Israel from prepare you for class lectures, May 4‐27 with course requirements beginning discussions and site visits. Always read before travel. the required text prior to the site visit. Course Requirements: Required texts include online readings 30% Participation linked through the CU Learn web site 20% Presentation or Web Page 50% Blogs or Research paper see details below YOUR PROFESSORS: As the Jewish Studies specialist of the Religion Program, Professor Deidre Butler brings together her general expertise in Jewish Studies and Religion with an emphasis on contemporary Jewish life, modern Jewish thought, Holocaust, and gender and sexuality. -

Muhammad Speaking of the Messiah: Jesus in the Hadīth Tradition

MUHAMMAD SPEAKING OF THE MESSIAH: JESUS IN THE HADĪTH TRADITION A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by Fatih Harpci (May 2013) Examining Committee Members: Prof. Khalid Y. Blankinship, Advisory Chair, Department of Religion Prof. Vasiliki Limberis, Department of Religion Prof. Terry Rey, Department of Religion Prof. Zameer Hasan, External Member, TU Department of Physics © Copyright 2013 by Fatih Harpci All Rights Reserved ii ABSTRACT Much has been written about Qur’ānic references to Jesus (‘Īsā in Arabic), yet no work has been done on the structure or formal analysis of the numerous references to ‘Īsā in the Hadīth, that is, the collection of writings that report the sayings and actions of the Prophet Muhammad. In effect, non-Muslims and Muslim scholars neglect the full range of Prophet Muhammad’s statements about Jesus that are in the Hadīth. The dissertation’s main thesis is that an examination of the Hadīths’ reports of Muhammad’s words about and attitudes toward ‘Īsā will lead to fuller understandings about Jesus-‘Īsā among Muslims and propose to non-Muslims new insights into Christian tradition about Jesus. In the latter process, non-Muslims will be encouraged to re-examine past hostile views concerning Muhammad and his words about Jesus. A minor thesis is that Western readers in particular, whether or not they are Christians, will be aided to understand Islamic beliefs about ‘Īsā, prophethood, and eschatology more fully. In the course of the dissertation, Hadīth studies will be enhanced by a full presentation of Muhammad’s words about and attitudes toward Jesus-‘Īsā. -

Adam and Seth in Arabic Medieval Literature: The

ARAM, 22 (2010) 509-547. doi: 10.2143/ARAM.22.0.2131052 ADAM AND SETH IN ARABIC MEDIEVAL LITERATURE: THE MANDAEAN CONNECTIONS IN AL-MUBASHSHIR IBN FATIK’S CHOICEST MAXIMS (11TH C.) AND SHAMS AL-DIN AL-SHAHRAZURI AL-ISHRAQI’S HISTORY OF THE PHILOSOPHERS (13TH C.)1 Dr. EMILY COTTRELL (Leiden University) Abstract In the middle of the thirteenth century, Shams al-Din al-Shahrazuri al-Ishraqi (d. between 1287 and 1304) wrote an Arabic history of philosophy entitled Nuzhat al-Arwah wa Raw∂at al-AfraÌ. Using some older materials (mainly Ibn Nadim; the ∑iwan al-Ìikma, and al-Mubashshir ibn Fatik), he considers the ‘Modern philosophers’ (ninth-thirteenth c.) to be the heirs of the Ancients, and collects for his demonstration the stories of the ancient sages and scientists, from Adam to Proclus as well as the biographical and bibliographical details of some ninety modern philosophers. Two interesting chapters on Adam and Seth have not been studied until this day, though they give some rare – if cursory – historical information on the Mandaeans, as was available to al-Shahrazuri al-Ishraqi in the thirteenth century. We will discuss the peculiar historiography adopted by Shahrazuri, and show the complexity of a source he used, namely al-Mubashshir ibn Fatik’s chapter on Seth, which betray genuine Mandaean elements. The Near and Middle East were the cradle of a number of legends in which Adam and Seth figure. They are presented as forefathers, prophets, spiritual beings or hypostases emanating from higher beings or created by their will. In this world of multi-millenary literacy, the transmission of texts often defied any geographical boundaries. -

Transcendence of God

TRANSCENDENCE OF GOD A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF THE OLD TESTAMENT AND THE QUR’AN BY STEPHEN MYONGSU KIM A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE PHILOSOPHIAE DOCTOR (PhD) IN BIBLICAL AND RELIGIOUS STUDIES IN THE FACULTY OF HUMANITIES AT THE UNIVERSITY OF PRETORIA SUPERVISOR: PROF. DJ HUMAN CO-SUPERVISOR: PROF. PGJ MEIRING JUNE 2009 © University of Pretoria DEDICATION To my love, Miae our children Yein, Stephen, and David and the Peacemakers around the world. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First, I thank God for the opportunity and privilege to study the subject of divinity. Without acknowledging God’s grace, this study would be futile. I would like to thank my family for their outstanding tolerance of my late studies which takes away our family time. Without their support and kind endurance, I could not have completed this prolonged task. I am grateful to the staffs of University of Pretoria who have provided all the essential process of official matter. Without their kind help, my studies would have been difficult. Many thanks go to my fellow teachers in the Nairobi International School of Theology. I thank David and Sarah O’Brien for their painstaking proofreading of my thesis. Furthermore, I appreciate Dr Wayne Johnson and Dr Paul Mumo for their suggestions in my early stage of thesis writing. I also thank my students with whom I discussed and developed many insights of God’s relationship with mankind during the Hebrew Exegesis lectures. I also remember my former teachers from Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, especially from the OT Department who have shaped my academic stand and inspired to pursue the subject of this thesis. -

From Adam to the End of Days: a Comparison of Bible and Quran

From Adam to the End of Days: A Comparison of Bible and Quran POL 4090 T-Th 1030-1150, Hatcher 026 Instructor: Alexander Orwin, [email protected] Stubbs 202, socially-distanced office hours by appointment in front of Quad Plaza Fountain Goals and Learning Objectives Everybody who knows the Bible is already familiar with many themes of the Quran, and vice-versa. These marked similarities in subject matter should make is somewhat easier for adherents of the three monotheistic faiths to talk to one another. In this course, we study a wide variety of themes in the Quran in light of their Biblical precedents. Every session will focus one of the themes, beginning with Creation and concluding with the Apocalypse. We will make modest use of the Muslim exegetical tradition, to the extent that it can be accessed in English (for example, www.altafsir.com, along with the commentary in the Study Quran). The rigorously comparative focus on the class is designed to deepen analytic skills and encourage cross-cultural appreciation. Since the three monotheistic religions and the tensions between them continue to play an enormous role in domestic and international politics, it will deepen our understanding of current events and hopefully foster constructive interaction between the different religious communities. Required Texts: Bible (use the edition of your choice) and Quran (Study Quran). If you can read in the original languages please do so: I will refer to them sparingly in class. Other materials will be provided in class. Syllabus: Jan. 12: Introduction Quran: Surah 1 (all) We will devote much of this session to introducing the subject, goals, and expectations of the class. -

Theology Today

Theology Today volume 67, N u m b e r 2 j u l y 2 0 1 0 EDITORIAL Christmas in July 123 JAMES F. KAY ARTICLES American Scriptures 127 C. CLIFTON BLACK Christian Spirituality in a Time of Ecological Awareness 169 KATHLEEN FISCHER The “New Monasticism” as Ancient-Future Belonging 182 PHILIP HARROLD Sexuality as Sacrament: An Evangelical Reads Andrew Greeley 194 ANTHONY L. BLAIR THEOLOGICAL TABLE TALK The Difference Calvin Made 205 R. BRUCE DOUGLASS CRITIC’S CORNER Thinking beyond Easy Tribalism 216 WALTER BRUEGGEMANN BOOK REVIEWS The Ten Commandments, by Patrick Miller 220 STANLEY HAUERWAS An Introduction to the New Testament Manuscripts and Their Texts, by D. C. Parker 224 SHANE BERG TT-67-2-pages.indb 1 4/21/10 12:45 PM Incarnation: The Person and Life of Christ by Thomas F. Torrance, edited by Robert T. Walker 225 PAUL D. MOLNAR Religion after Postmodernism: Retheorizing Myth and Literature by Victor E. Taylor 231 TOM BEAUDOIN Practical Theology: An Introduction, by Richard R. Osmer 234 JOYCE ANN MERCER Boundless Faith: The Global Outreach of American Churches by Robert Wuthnow 241 RICHARD FOX YOUNG The Hand and the Road: The Life and Times of John A. Mackay by John Mackay Metzger 244 JOHN H. SINCLAIR The Child in the Bible, Marcia J. Bunge, general editor; Terence E. Fretheim and Beverly Roberts Gaventa, coeditors 248 KAREN-MARIE YUST TT-67-2-pages.indb 2 4/21/10 12:45 PM James F. Kay, Editor Gordon S. Mikoski, Reviews Editor Blair D. Bertrand, Editorial Assistant EDITORIAL COUNCIL Iain R. -

Dawud and Jalut (David and Goliath) 1

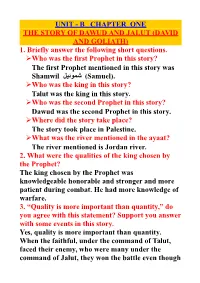

UNIT - B CHAPTER ONE THE STORY OF DAWUD AND JALUT (DAVID AND GOLIATH) 1. Briefly answer the following short questions. ➢Who was the first Prophet in this story? The first Prophet mentioned in this story was .(Samuel) شموئيل Shamwil ➢Who was the king in this story? Talut was the king in this story. ➢Who was the second Prophet in this story? Dawud was the second Prophet in this story. ➢Where did the story take place? The story took place in Palestine. ➢What was the river mentioned in the ayaat? The river mentioned is Jordan river. 2. What were the qualities of the king chosen by the Prophet? The king chosen by the Prophet was knowledgeable honorable and stronger and more patient during combat. He had more knowledge of warfare. 3. “Quality is more important than quantity,” do you agree with this statement? Support you answer with some events in this story. Yes, quality is more important than quantity. When the faithful, under the command of Talut, faced their enemy, who were many under the command of Jalut, they won the battle even though they were few in number. Because of their faith in Allah they were able to defeat their enemy. 4. What were the motivation techniques used by the king to gain victory and to defeat the enemies? When Talut set out with his forces, he said to them, “God will test you with a river; whoever drinks from it is not with me and whoever does not drink is with me. However there will be no blame upon one who sips only a handful from it. -

You Will Be Like the Gods”: the Conceptualization of Deity in the Hebrew Bible in Cognitive Perspective

“YOU WILL BE LIKE THE GODS”: THE CONCEPTUALIZATION OF DEITY IN THE HEBREW BIBLE IN COGNITIVE PERSPECTIVE by Daniel O. McClellan A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES Master of Arts in Biblical Studies We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard ............................................................................... Dr. Craig Broyles, PhD; Thesis Supervisor ................................................................................ Dr. Martin Abegg, PhD; Second Reader TRINITY WESTERN UNIVERSITY December, 2013 © Daniel O. McClellan Table of Contents Chapter 1 – Introduction 1 1.1 Summary and Outline 1 1.2 Cognitive Linguistics 3 1.2.1 Profiles and Bases 8 1.2.2 Domains and Matrices 10 1.2.3 Prototype Theory 13 1.2.4 Metaphor 16 1.3 Cognitive Linguistics in Biblical Studies 19 1.3.1 Introduction 19 1.3.2 Conceptualizing Words for “God” within the Pentateuch 21 1.4 The Method and Goals of This Study 23 Chapter 2 – Cognitive Origins of Deity Concepts 30 2.1 Intuitive Conceptualizations of Deity 31 2.1.1 Anthropomorphism 32 2.1.2 Agency Detection 34 2.1.3 The Next Step 36 2.2. Universal Image-Schemas 38 2.2.1 The UP-DOWN Image-Schema 39 2.2.2 The CENTER-PERIPHERY Image-Schema 42 2.3 Lexical Considerations 48 48 אלהים 2.3.1 56 אל 2.3.2 60 אלוה 2.3.3 2.4 Summary 61 Chapter 3 – The Conceptualization of YHWH 62 3.1 The Portrayals of Deity in the Patriarchal and Exodus Traditions 64 3.1.1 The Portrayal of the God of the Patriarchs -

The Nature of David's Kingship at Hebron: an Exegetical and Theological Study of 2 Samuel 2:1-5:5

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertations Graduate Research 2019 The Nature of David's Kingship at Hebron: An Exegetical and Theological Study of 2 Samuel 2:1-5:5 Christian Vogel Andrews University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations Part of the Biblical Studies Commons Recommended Citation Vogel, Christian, "The Nature of David's Kingship at Hebron: An Exegetical and Theological Study of 2 Samuel 2:1-5:5" (2019). Dissertations. 1684. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations/1684 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT THE NATURE OF DAVID’S KINGSHIP AT HEBRON: AN EXEGETICAL AND THEOLOGICAL STUDY OF 2 SAMUEL 2:1—5:5 by Christian Vogel Adviser: Richard M. Davidson ABSTRACT OF GRADUATE STUDENT RESEARCH Dissertation Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary Title: THE NATURE OF DAVID’S KINGSHIP AT HEBRON: AN EXEGETICAL AND THEOLOGICAL STUDY OF 2 SAMUEL 2:1—5:5 Name of researcher: Christian Vogel Name and degree of faculty adviser: Richard M. Davidson, Ph.D. Date completed: June 2019 The account of David’s reign at Hebron found in 2 Samuel 2:1—5:5 constitutes a somewhat neglected, yet crucial part of the David narrative, chronicling David’s first years as king. This dissertation investigates these chapters by means of a close reading of the Hebrew text in order to gain a better understanding of the nature of David’s kingship as it is presented in this literary unit. -

Islam Is Your Birthright

اﻹسﻻم دين الفطرة ISLAM IS YOUR BIRTHRIGHT An open call to the sincere followers of Moses and Jesus, true prophets sent by Allah, to encourage dialogue and understanding amongst people of different faiths in the spirit of tolerance and respect In this book, you will read: Islam‘s basic principles and characteristics Eleven facts about Jesus (may peace be upon him) Nineteen abandoned biblical teachings revived by Islam Twenty arguments refuting the doctrines of ‗original sin‘ and redemption (absolution of sins through Jesus' sacrifice) Twenty six proofs from the Bible of Muhammad's prophethood Compiled by Majed S. Al-Rassi Revised and Expanded 2009 1 Islam is Your Birthright NO DOUBT THIS LIFE IS AN EXAMINATION WHICH NEEDS YOUR FULL CONSIDERATION AS TO WHAT YOU WILL TAKE TO YOUR FINAL DESTINATION ONLY TRUE BELIEF AND GOOD DEEDS ARE YOUR WAY TO SALVATION (Muhammad Sherif) 1 Islam is Your Birthright 2 Contents About the word Lord ............................................................................. 6 Preface ........................................................................................ 7 Introduction ........................................................................................ 9 I. Proof of Allah's Existence ..................................................... 12 II. The Purpose of Creation ....................................................... 15 III. Monotheism, the Message of All Prophets ........................... 18 IV. The Basic Message of Islam ................................................. 21 -

Changing Views 100 Years After the Exhibition Masterpieces of Muhammedan Art in Munich

Changing Views 100 Years After the Exhibition Masterpieces of Muhammedan Art in Munich September 2010 – February 2011 Exhibitions Discussions Films Concerts Readings Lectures www.changing-views.de Dance Performances 1 Contents Introduction Changing Views 100 Years After the Exhibition Masterpieces of Muhammedan Art in Munich Munich, September 2010 – February 2011 Exhibitions 2 Interactions with the «Other» and the unknown have been a Architecture 12 continuous source of transformation and constitute occasions Film 17 for cultural self-reflection, providing impetus towards rethinking Society 22 former perspectives and prejudices, and uncovering new ways Calendar 28 of thinking – Changing Views. Koran 32 Arts 37 The exhibition Masterpieces of Muhammedan Art, which took Music | Poetry 45 place in Munich in 1910, marked a turning point in the historical Script 50 conception of the Islamic world. This monumental exhibition Dance 52 displayed almost 3,600 artefacts from various Muslim regions. Edition Notice 56 It was intended to distinguish itself from the prevailing oriental and exotic fantasies of the time and thus set a new benchmark for the reception of Islamic arts in Europe. In recognition of the 100th anniversary of this legendary exhibi- tion, the Department of Arts and Culture and various affiliated museums, galleries, and educational facilities have organised a comprehensive series of exhibitions and related events. This interdisciplinary programme, entitled Changing Views, explores Islamic artistic and cultural traditions from multiple