Extreme Speech in Myanmar: the Role of State Media in the Rohingya Forced Migration Crisis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rohingnya and the Concept of Conflict Resolution

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research (ASSEHR), volume 140 3rd Annual International Seminar and Conference on Global Issues (ISCoGI 2017) Rohingnya and The Concept of Conflict Resolution Fitria Martanti, Gadis Herningtyasari Fazulty of Islamic Studies Universitas Wahid Hasyim Semarang, Indonesia [email protected] Abstract—Rohingnya conflict that occurred in prolonged conflicts and reaping responses from several countries in the due to things that are complex. Some of the problems that world as well as the response from the United Nations are triggered this were sentiments to religion, ethnicity, social, conflict between ethnic groups in Myanmar. The conflict economic and political issues. This paper will provide an occurred between ethnic Rohingnya which in fact the overview of the concept of conflict resolution that can be given majority of Muslims and ethnic Rakhine Buddhist majority. as a solution about conflict resolution in Myanmar. This research is a qualitative research that reveals phenomena The prolonged and non-existent conflicts must have been related to conflict Rohingnya, both the root of the conflict and triggered by several issues, especially in the absence of the concept of conflict resolution that can be given. Concept of concrete resolutions by the Myanmar government with conflict resolution by looking at the source of the problem and related parties. The great conflicts that occurred during 39 formulating a form of conflict resolution by adopting conflict years since 1978 until now still leaves a lot of problems that resolution in Indonesia mainly from conflict resolution in Poso, need to be solved. Ambon and Sampit. Forms of conflict resolution can be done Myanmar is a country in Southeast Asia which has the by conflict resolution based on political recognition. -

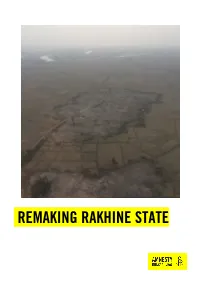

Remaking Rakhine State

REMAKING RAKHINE STATE Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2017 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: Aerial photograph showing the clearance of a burnt village in northern Rakhine State (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. © Private https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2017 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: ASA 16/8018/2018 Original language: English amnesty.org INTRODUCTION Six months after the start of a brutal military campaign which forced hundreds of thousands of Rohingya women, men and children from their homes and left hundreds of Rohingya villages burned the ground, Myanmar’s authorities are remaking northern Rakhine State in their absence.1 Since October 2017, but in particular since the start of 2018, Myanmar’s authorities have embarked on a major operation to clear burned villages and to build new homes, security force bases and infrastructure in the region. -

Download File

UNICEF ADVOCACY ALERT | August 2019 UNICEF ADVOCACY ALERT | August 2019 BEYOND SURVIVAL SURVIVAL ROHINGYA REFUGEE ROHINGYACHILDREN REFUGEE IN BANGLADESH CHILDREN IN BANGLADESH WANT TO LEARN WANT TO LEARN UNICEF Bangladesh thanks its partners and donors without whom its work on behalf of Rohingya children would not be possible Cover photo: Children at a UNICEF-supported Learning Centre in Kutupalong refugee camp © UNICEF/Brown Published by UNICEF Bangladesh BSL Offi ce Complex, 1 Minto Road, Dhaka – 1000, Bangladesh © United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) August 2019 #AChildisAChild BEYOND SURVIVAL ROHINGYA REFUGEE CHILDREN IN BANGLADESH WANT TO LEARN Refugee Population in Cox’s Bazar District April 2019 | Sources: ISCG, RRRC, UNHCR, IOM-NPM, Site Management Sector | Projection: BUTM CONTENTS 4 BEYOND SURVIVAL 6 Frustration in a fragile setting 8 DESPERATE TO LEARN 10 First steps towards quality learning 12 Big issues remain 14 Adolescents risk missing out 18 A CLARION CALL FOR EDUCATION 20 MEETING THE NEEDS OF ROHINGYA REFUGEE CHILDREN 22 Building bridges between the communities 24 Darkness exposes women and girls to danger 27 At the mercy of traffi ckers 30 Vigilance against the threat of cholera 32 Youngest children remain at risk 34 Piped networks give more families access to safe water 38 CALL TO ACTION 42 UNICEF BANGLADESH ROHINGYA RESPONSE HIGHLIGHTS 2017-19 43 UNICEF FUNDING NEEDS 2019 Monsoon rainclouds loom overhead as Mohamed Amin (facing camera centre) and other family members rebuild their shelter which was destroyed during heavy monsoon rains on the night of July 6 2019. In the space of 25 days in July, authorities in the vast Rohingya camps had to assist over 5,700 refugee households with damaged shelters. -

Burma's Long Road to Democracy

UNITED STATES InsTITUTE OF PEACE www.usip.org SPECIAL REPORT 1200 17th Street NW • Washington, DC 20036 • 202.457.1700 • fax 202.429.6063 ABOUT THE REPORT Priscilla Clapp A career officer in the U.S. Foreign Service, Priscilla Clapp served as U.S. chargé d’affaires and chief of mission in Burma (Myanmar) from June 1999 to August 2002. After retiring from the Foreign Service, she has continued to Burma’s Long Road follow events in Burma closely and wrote a paper for the United States Institute of Peace entitled “Building Democracy in Burma,” published on the Institute’s Web site in July 2007 as Working Paper 2. In this Special to Democracy Report, the author draws heavily on her Working Paper to establish the historical context for the Saffron Revolution, explain the persistence of military rule in Burma, Summary and speculate on the country’s prospects for political transition to democracy. For more detail, particularly on • In August and September 2007, nearly twenty years after the 1988 popular uprising the task of building the institutions for stable democracy in Burma, public anger at the government’s economic policies once again spilled in Burma, see Working Paper 2 at www.usip.org. This into the country’s city streets in the form of mass protests. When tens of thousands project was directed by Eugene Martin, and sponsored by of Buddhist monks joined the protests, the military regime reacted with brute force, the Institute’s Center for Conflict Analysis and Prevention. beating, killing, and jailing thousands of people. Although the Saffron Revolution was put down, the regime still faces serious opposition and unrest. -

Rohingya Refugee Crisis and Forest Cover Change in Teknaf, Bangladesh

remote sensing Article Rohingya Refugee Crisis and Forest Cover Change in Teknaf, Bangladesh Mohammad Mehedy Hassan 1,*, Audrey Culver Smith 1, Katherine Walker 1 ID , Munshi Khaledur Rahman 2 and Jane Southworth 1 1 Department of Geography, University of Florida, 3141 Turlington Hall, P.O. Box 117315, Gainesville, FL 32611-7315, USA; audreyculver@ufl.edu (A.C.S.); kqwalker@ufl.edu (K.W.); jsouthwo@ufl.edu (J.S.) 2 Department of Geography, Virginia Tech, 115 Major Williams Hall, 220 Stanger Street, Blacksburg, VA 24061, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: mehedy@ufl.edu; Tel.: +1-352-745-9364 Received: 6 March 2018; Accepted: 25 April 2018; Published: 30 April 2018 Abstract: Following a targeted campaign of violence by Myanmar military, police, and local militias, more than half a million Rohingya refugees have fled to neighboring Bangladesh since August 2017, joining thousands of others living in overcrowded settlement camps in Teknaf. To accommodate this mass influx of refugees, forestland is razed to build spontaneous settlements, resulting in an enormous threat to wildlife habitats, biodiversity, and entire ecosystems in the region. Although reports indicate that this rapid and vast expansion of refugee camps in Teknaf is causing large scale environmental destruction and degradation of forestlands, no study to date has quantified the camp expansion extent or forest cover loss. Using remotely sensed Sentinel-2A and -2B imagery and a random forest (RF) machine learning algorithm with ground observation data, we quantified the territorial expansion of refugee settlements and resulting degradation of the ecological resources surrounding the three largest concentrations of refugee camps—Kutupalong–Balukhali, Nayapara–Leda and Unchiprang—that developed between pre- and post-August of 2017. -

Rohingya Crisis: an Analysis Through a Theoretical Perspective

International Relations and Diplomacy, July 2020, Vol. 8, No. 07, 321-331 doi: 10.17265/2328-2134/2020.07.004 D D AV I D PUBLISHING Rohingya Crisis: An Analysis Through a Theoretical Perspective Sheila Rai, Preeti Sharma St. Xavier’s College, Jaipur, India The large scale exodus of Rohingyas to Bangladesh, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Thailand as a consequence of relentless persecution by the Myanmar state has gained worldwide attention. UN Secretary General, Guterres called it “ethnic cleansing” and the “humanitarian situation as catastrophic”. This catastrophic situation can be traced back to the systemic and structural violence perpetrated by the state and the society wherein the Burmans and Buddhism are taken as the central rallying force of the narrative of the nation-state. This paper tries to analyze the Rohingya discourse situating it in the theoretical precepts of securitization, structural violence, and ethnic identity. The historical antecedents and particular circumstances and happenings were construed selectively and systematically to highlight the ethnic, racial, cultural, and linguistic identity of Rohingyas to exclude them from the “national imagination” of the state. This culture of pervasive prejudice prevailing in Myanmar finds manifestation in the legal provisions whereby certain peripheral minorities including Rohingyas have been denied basic civil and political rights. This legal-juridical disjunction to seal the historical ethnic divide has institutionalized and structuralized the inherent prejudice leveraging the religious-cultural hegemony. The newly instated democratic form of government, by its very virtue of the call of the majority, has also been contributed to reinforce this schism. The armed attacks by ARSA has provided the tangible spur to the already nuanced systemic violence in Myanmar and the Rohingyas are caught in a vicious cycle of politicization of ethnic identity, structural violence, and securitization. -

Siti Umayatun, S.Hum. TESIS

PERAN KOREA MUSLIM FEDERATION (KMF) DALAM PERTUMBUHAN ISLAM DI KOREA SELATAN TAHUN 1967-2015 M Disusun Oleh : Siti Umayatun, S.Hum. NIM : 1520510121 TESIS Diajukan Kepada Pascasarjana UIN Sunan Kalijaga Untuk Memenuhi Salah Satu Syarat Guna Memperoleh Gelar Master of Arts (M. A) Program Studi Interdisciplinary Islamic Studies (IIS) Konsentrasi Sejarah KebudayaanIslam YOGYAKARTA 2017 ABSTRAK Pada era Modern, bersamaan dengan Perang Korea tahun 1950-1953 M benih ajaran agama Islam mulai tumbuh di semenanjung Korea Selatan melalui kontak hubungan dengan pasukan perdamaian Turki. Dakwah bil hal tentara Turki selama terjadi perang melahirkan beberapa Muallaf generasi pertama Muslim Korea. Jumlah mereka pertahunnya meningkat sehingga terbentuk perkumpulan Muslim Korea dan tahun 1967 M menjadi organisasi Korea Muslim Federation (KMF) yang statusnya diakui oleh pemerintah Korea bahkan diberi surat izin mendirikan bangunan. Semua Muslim yang diorganisir KMF awalnya benar-benar bagian integral dari bangsa Korea yang menjadi Muallaf bukan karena kedatangan imigran Muslim dari negara-negara Islam. Sejak tahun 1970-an pemerintah Korea membantu KMF dalam perkembangan Islam, padahal selama itu mereka simpati pada Zionis dan pro Israel bahkan sejak masa kemerdekaan sampai sekarang berada di bawah naungan Amerika. Pemerintah Korea memperlakukan Muslim atas dasar sama dengan kelompok agama lainnya, tidak mendiskriminasi bahkan membuka pintu lebar-lebar dakwah KMF dengan memberikan sebidang tanah untuk pembangunan masjid dan universitas Islam. Meski Islam agama baru dan minoritas di Korea namun memiliki posisi terhormat dan stategis. Dalam memobilisasi perkembangan Islam, KMF melakukan kaderisasi mengirim beberapa pemuda Muslim Korea ke negara- negara Muslim untuk belajar Islam dan melakukan riset. Terlihat bahwa minoritas Muslim Korea punya nasip lebih cerah dan menjanjikan jika dibandingkan dengan keadaan minoritas Muslim lainnya. -

What About the Rohingya?

UPPSALA UNIVERSITY Department of Theology Master Programme in Religion in Peace and Conflict Master thesis, 30 credits Spring, 2019 Supervisor: Håkan Bengtsson What about the Rohingya? A study searching for power relations in different levels of society Ewa Einarsson Abstract This study aims to search for patterns that demonstrate power relations. It specifically seeks to identify patterns in the power relations in the Rohingya conflict and understand the established power relations at different levels in society, which could provide a picture of the social world within the context of historical, ethnic, cultural, religious and political circumstances. Moreover, this study illustrates the Rohingya population’s experience with relations of power. The ongoing conflict in Myanmar, which is based on religion, ethnicity and politics, is seemingly without any solution. Myanmar is depicted as a country that has lost both hope and legitimacy for the political system and has reduced chances to establish a society in which all the minorities are included across the spheres of society. Finding a bright future for the Rohingya population might be difficult; nevertheless, this study seeks to enhance the understanding of the ongoing conflict and the underlying power relations. 2 Table of Contents A study searching for power relations in different levels of society ................................................................. 1 ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................................... -

FOREWORD in 2017, Asia and the Pacific Was Home to More Than 60 Per Cent of the World’S Population

REGIONAL SUMMARIES FOREWORD In 2017, Asia and the Pacific was home to more than 60 per cent of the world’s population. With some 4.4 billion people, the region is an engine for global development, characterized by economic growth, rising living standards, and people on the move seeking new opportunities. However, in 2017, millions of people were not following this upward trajectory. The region hosted 9.5 million people of concern to UNHCR, including 4.2 million refugees, 2.7 million IDPs, and an estimated 2.2 million stateless persons. Of the total population of concern to UNHCR, half were children; more than half were women and girls; and many had no nationality, documentation or place to call home. The long-standing tradition of hospitality towards many displaced people remained strong across the region. This was demonstrated by the remarkable response of Bangladesh, which kept its borders open to nearly 655,000 stateless refugees fleeing violence in Myanmar. The influx dramatically altered the operational context for UNHCR in Bangladesh. As a result of the urgent humanitarian needs, UNHCR ramped up its capacity in support of refugees, the Government and local communities generously hosting them. The solutions to this crisis lie in Myanmar, and it is there that the search must start for them. The efforts needed to enable the voluntary and sustainable repatriation of refugees failed to materialize in 2017, and they must begin with humanitarian access for UNHCR. Preserving the right of return, however, remained a central priority for UNHCR and Asia and the Office welcomed the commitments made by Bangladesh and Myanmar on dignified, safe, and voluntary repatriation in 2017. -

Myanmar: the Dark Side of the Rohingya Muslim Minority

Myanmar: The Dark Side of the Rohingya Muslim Minority by Col. (res.) Dr. Raphael G. Bouchnik-Chen BESA Center Perspectives Paper No. 970, October 9, 2018 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: A UNHRC report has found Myanmar’s authorities responsible for “the gravest crimes under international law” against the Rohingya Muslim minority – crimes that led to a massive exodus to Bangladesh. The report concludes that the army must be investigated for genocide against the Rohingya. This blunt condemnation of the Myanmar authorities does not correspond to solid intelligence data proving terror attacks by Rohingya’s ARSA militants against government assets and the killing of military and police personnel, as well as Buddhist citizens. Several conclusions of the UNHRC Mission ought to be revisited. In her book Weapons of Mass Migration: Forced Displacement, Coercion and Foreign Policy (2010), Prof. Kelly M. Greenhill, a former US foreign policy consultant, argues that engineered migration is a strategy that has been used by governments and organizations as an instrument of persuasion in the international arena. In other words, manipulation of mass migration can be used as a weapon to exert pressure on governments for political ends. The latest refugee case to have attracted international attention was the 700,000 Rohingya who recently fled Myanmar and crossed into Bangladesh. A special UN fact-finding mission assigned by the UN Human Rights Council (UNHRC) delivered its final report on September 17, 2018. “It is hard to fathom the level of brutality of Tatmadaw operations, its total disregard for civilian life,” Marzuki Darusman, the head of the Mission, told the UNHRC, referring to the nation's military. -

1 Multidimensional Social Crisis and Religious Violence In

1 Journal of Culture and Values in Education Suntana, I., Tresnawaty, B., Multidimensional Social Crisis Multidimensional Social Crisis and Religious Violence in Southeast Asia: Regional Strategic Agenda, Weak Civilian Government, Triune Crime, Wealth Gaps, and Coopted Journalism Ija Suntana* Betty Tresnawaty UIN Sunan Gunung Djati Bandung *Corresponding Author: [email protected] Received : 2020- November-03 Rev. Req. : 2021-January-07 Accepted : 2021-February-01 10.46303/jcve.2021.2 Note: This is the forthcoming version of the article. For final version, please see https://doi.org/10.46303/jcve.2021.2 This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/) Abstract Five factors have contributed greatly to religious violence in the Southeast Asia: the regional strategic agenda of a great power; weak civilian government; triune crimes and scholar phobia; wealth gaps; and coopted journalism. These are the roots of the increase of religion-related violence in this region. Religious violence in this area is a psychological symptom of a society facing complex social situations related to power struggles and economic domination. As an evidence, the Rohingya crisis in Myanmar is not caused by a clash of beliefs but by those five factors, thus it turns into a prolonged and complex humanitarian crisis that it also gives social impacts into surrounding countries. Therefore, solving the problem of religious violence in Southeast Asia must address these five causes. Keywords: Religious violence; islamophobia; peace journalism Introduction There are several factors that cause recent sharp increase of, and protracted, religious conflict in Southeast Asia. -

Weekly Situation Report 3

Weekly Situation Report # 2 Date of issue: 8 November 2017 Period covered: 1 to 7 November 2017 Location: Bangladesh Emergency type: Arrival of Rohingya population from Myanmar following conflict in Rakhine state 609 000 300 000 105 1727 1.2 million new arrivals refugees from Myanmar children over 1 year of age people targeted for in Bangladesh who arrived previously vaccinated with oral cholera humanitarian assistance in B angladesh vaccine (58% of target at end of day 3 of 6-day campaign) KEY HIGHLIGHTS As of 6 November 2017, the cumulative number of new arrivals in all sites (Ukiah, Teknaf, Cox’s Bazar and Ramu) was 609 0001. This number includes over 329 000 arrivals in Kutupalong Balukhali expansion site, 230 000 in other camps and settlements, and 46 000 arrivals in host communities. According to data generated by WHO’s disease early warning and response system (EWARS), a total of 245 389 consultations were provided to the new arrivals and other vulnerable populations between 25 August to 4 November 2017. A total of 412 suspected cases of measles have been reported through EWARS. Case investigation/finding is ongoing. The preliminary results of a recent inter-agency assessment conducted in Kutupalong refugee camp from 22 to 28 October 2017 shows that severe acute malnutrition rates are running at 7.5% (well above emergency thresholds). The second phase of an oral cholera vaccination campaign started on 4 November. Around 180 000 children aged between one and five years will be given a second dose of oral cholera vaccine for added protection, and 210 000 children under five years of age will be given oral polio vaccine (bOPV).