Mochtar Lubis Writes with Lucidity and Frankness of the Dark Side of Political and Social Life in Djakarta

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pramoedya's Developing Literary Concepts- by Martina Heinschke

Between G elanggang and Lekra: Pramoedya's Developing Literary Concepts- by Martina Heinschke Introduction During the first decade of the New Order, the idea of the autonomy of art was the unchallenged basis for all art production considered legitimate. The term encompasses two significant assumptions. First, it includes the idea that art and/or its individual categories are recognized within society as independent sub-systems that make their own rules, i.e. that art is not subject to influences exerted by other social sub-systems (politics and religion, for example). Secondly, it entails a complex of aesthetic notions that basically tend to exclude all non-artistic considerations from the aesthetic field and to define art as an activity detached from everyday life. An aesthetics of autonomy can create problems for its adherents, as a review of recent occidental art and literary history makes clear. Artists have attempted to overcome these problems by reasserting social ideals (e.g. as in naturalism) or through revolt, as in the avant-garde movements of the twentieth century which challenged the aesthetic norms of the autonomous work of art in order to relocate aesthetic experience at a pivotal point in relation to individual and social life.* 1 * This article is based on parts of my doctoral thesis, Angkatan 45. Literaturkonzeptionen im gesellschafipolitischen Kontext (Berlin: Reimer, 1993). I thank the editors of Indonesia, especially Benedict Anderson, for helpful comments and suggestions. 1 In German studies of literature, the institutionalization of art as an autonomous field and its aesthetic consequences is discussed mainly by Christa Burger and Peter Burger. -

JSS 072 0A Front

7-ro .- JOURNAL OF THE SIAM SOCIETY JANUAR ts 1&2 "· THE SIAM SOCIETY PATRON His Majesty the King VICE-PATRONS Her Majesty the Queen Her Royal Highness the Princess Mother Her Royal Highness Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn HON . M E MBE R S The Ven. Buddhadasa Bhikkhu The Ven. Phra Rajavaramuni (Payu!to) Mr. Fua Haripitak Dr. Mary R. Haas Dr. Puey Ungphakorn Soedjatmoko Dr. Sood Saengvichien H.S.H. Prince Chand Chirayu Rajni Professor William J. Gedney HON. VIC E-PRESIDF.NTS Mr. Alexander B. Griswold Mom Kobkaew Abhakara Na Ayudhya H.S.H. Prince Subhadradis Diskul COU N CIL.. OF 'I'HE S IAM S O C IETY FOR 19841 8 5 President M.R. Patanachai Jayant Vice-President and Leader, Natural History Section Dr. Tern Smitinand Vice-President Mr. Dacre F.A. Raikes Vice-President Dr. Svasti Srisukh Honorary Treasurer Mrs. Katherine B. Buri Honorary Secretary Mrs. Nongyao Narumit Honorary Editor. Dr. Tej Bunnag Honorary Librarian Khi.m .Varun Yupha Snidvongs Assistant Honorary Treasurer Mr. James Stent Assistant Honorary Secretary Mrs. Virginia M. Di Crocco Assistant Honorary Librarian Mrs. Bonnie Davis Mr. Sulak Sivaraksa Mr. Wilhelm Mayer Mr. Henri Pagau-Clarac Dr. Pornchai Suchitta Dr. Piriya Krairiksh Miss A.B. Lambert Dr. Warren Y. Brockelman Mr. Rolf E. Von Bueren H.E. Mr. W.F.M. Schmidt Mr. Rich ard Engelhardt Mr. Hartmut Schneider Dr. Thawatchai Santisuk Dr. Rachit Buri JSS . JOURNAL ·"' .. ·..· OF THE SIAM SOCIETY 75 •• 2 nopeny of tbo ~ Society'• IJ1nQ BAN~Olt JANUARY & JULY 1.984 volume 72 par_ts 1. & 2 THE SIAM SOCIETY 1984 • Honorary Editor : Dr. -

ASIAN REPRESENTATIONS of AUSTRALIA Alison Elizabeth Broinowski 12 December 2001 a Thesis Submitted for the Degree Of

ABOUT FACE: ASIAN REPRESENTATIONS OF AUSTRALIA Alison Elizabeth Broinowski 12 December 2001 A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University ii Statement This thesis is my own work. Preliminary research was undertaken collaboratively with a team of Asian Australians under my co-direction with Dr Russell Trood and Deborah McNamara. They were asked in 1995-96 to collect relevant material, in English and vernacular languages, from the public sphere in their countries of origin. Three monographs based on this work were published in 1998 by the Centre for the Study of Australia Asia Relations at Griffith University and these, together with one unpublished paper, are extensively cited in Part 2. The researchers were Kwak Ki-Sung, Anne T. Nguyen, Ouyang Yu, and Heidi Powson and Lou Miles. Further research was conducted from 2000 at the National Library with a team of Chinese and Japanese linguists from the Australian National University, under an ARC project, ‘Asian Accounts of Australia’, of which Shun Ikeda and I are Chief Investigators. Its preliminary findings are cited in Part 2. Alison Broinowski iii Abstract This thesis considers the ways in which Australia has been publicly represented in ten Asian societies in the twentieth century. It shows how these representations are at odds with Australian opinion leaders’ assertions about being a multicultural society, with their claims about engagement with Asia, and with their understanding of what is ‘typically’ Australian. It reviews the emergence and development of Asian regionalism in the twentieth century, and considers how Occidentalist strategies have come to be used to exclude and marginalise Australia. -

THE MANGO TREE ...Suvimalee

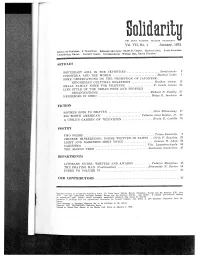

II oli i UBI BONI TACENT. MALUM Vol. VII, No.1 January, 1972 Editor and publisher: F. Sionil Jose. Editorial Advirsers: Onofre D. Corpuz, Mochtar Lubis, Sulak Sivaraksa. Contributing Editor: Leonard Casper. Correspondents:, Willam Hsu, Edwin Thumb"". -- ARTICLES SOUTHEAST ASIA IN THE SEVENTIES ...................... Soedjahno7co 3 INDONESIA AND THE WORLD .............................. Mochtar Liibü 7 SOME OBSERVATIONS ON THE PROMOTION OF JAPANESE- INDONESIAN CULTURAL :RELATIONS ............... Rosihan Anwa-r 12 SMALL FAMILY NORM FOR FILIPINOS.................. F. Landa Jocano 2-4 LIFE STYLE OF THE URBAN POOR AND PEOPLE'S ORGANIZATIONS .................................. Richard P: Poethig 37 NEIGHBORS IN CEBU .................................... Helga E. Jacobson 44 FICTION MOTHER GOES TO HEAVEN.............................. SitorSitumorang 17 BIG WHITE AMERICAN . .. .. .. Federico Licsi Espino, Jr. 30 A CHILD'S GARDEN OF TELEVISION .................... Erwin E. Castillo 35 POETRY TWO POEMS .......................................,........ Trisno Siimci'djo 2 CHINESE IMPRESSIONS: POEMS WRITTEN IN TAIPEI.. Cirilo F. Bautista 22 LIGHT AND DARKNESS MEET TWICE ..........;........ Gemino H. Abad 29 CARISSIMA . .. Tita Lacambra-Ayala 36 THE MANGO TREE ................................... Suvimalee Gunaratna 47 LITERARY NOTES: WRITERS AND AWARDS ........... Federico Mangahas 48 THE PRAYING MAN (Contimiation) .................... Bienvenido N. Santos' 54 INDEX TO VOLUME VI .................................................... 51 CONTRIBUTORS .. .. 51 531 Padre Faura¡ Ermitai Manila¡ Philippines.. Europe and the Amerlcas $.95; Asia Europe and .the Americas S10.00. Asia $8.50. A stamped self-addressed envelope or manuscripts otherwise they carinot be returned. Solidarity is for Cultural Freedom with Office at 104 Boulevard Haussmann Paris Be. Franc-e. Views expressed in Solidarity Magazine are to be attributed to th~ aulhors. Copyright 1967, SOLIDARIDAD Publishing House. ' Entered as Second-Class Matter at the Manila Post Office on February 7, 1968. -

Pustaka-Obor-Indonesia.Pdf

Foreign Rights Catalogue ayasan Pustaka Obor Indonesia, a modestly sized philanthropy active in the Yfield of cultural and intellectual development through scholarly publishing. It’s initial focus to publish books from various languages into the Indonesian language. Among its main interest is books on human and democratic rights of the people. Yayasan Pustaka Obor Indonesia was set up as an Indonesian legal entity in 1978. The Obor Indonesia office coordinates the careful work of translation and revision. An editorial Board is in charge of program selection. Books are published locally and placed on the market at a low subsidized price within reach of students and the general reader. Obor also plays a service role, helping specialized organizations bring out their research in book form. It is the Purpose of Yayasan Pustaka Obor Indonesia, to widen and develop the perspective of Indonesia’s growing intellectual community, by publishing in Bahasa Indonesia -- and other appropriate languages -- literate and socially significant works. __________________ Contact Detail: Dian Andiani Address: Jl. Plaju No. 10 Jakarta Indonesia 10230 E-mail: [email protected]/[email protected] Web: www.obor.or.id mobile: +6281286494677 2 CATALOGUE Literature CATALOGUE 3 Harimau!Harimau!|Tiger! Tiger! Author: Mochtar Lubis | ISBN: 978-979-461-109-8 | “Tiger! Tiger!” received an award from ‘Buku Utama’ foundation as the best literature work in 1975. This book illustrated an adventurous story in wild jungle by a group of resin collector who was hunted by a starving tiger. For days, they tried to escape but they became victims. The tiger pounced on them one by one. -

REVIEWS Thailand : Buddhist Kingdom As Modern Nation-State Charles F

331 Journal of The Siam Society REVIEWS Thailand : Buddhist Kingdom as Modern Nation-State Charles F. Keyes, Westview Press, Boulder and London, 1987. This book is part of the series of Westview Profiles/Nations of Contemporary Asia. Though many volumes have been published on Thailand, this book deserves special attention. It is one of the few books on Thai politics and society ever written by an anthropologist. In fact, the book exemplifies par excellence the genre, political anthropology. The book is comprised of eight chapters. Chapter one presents a brief geography and background on the peoples of Thai society. Described are the origins of the present land and the diverse peoples which constitute the Thai nation. Chapter two presents an historical overview of the development of Thai traditions. Chapter three deals with the formation of the Thai nation-state. Chapter four analyses politics in Thai society by showing the process and conditions by which the military has come to dominate Thai politics. Also, the author in this chapter analyses the re-emerging role of the monarchy in politics. Chapter five describes the Thai polity after the 1973 "revolution". Again in this chapter, the author tries to show that Thai politics is essentially dominated by two important institutions in Thai society, namely, the monarchy and the military. Professor Keyes praises King Bhumibol for having "succeeded in restoring the Thai monarchy as a central pillar of the modem nation state" (p. 210). U.S. influence on Thailand, particularly during the Sarit and Thanom periods is also noted. Chapter six analyses the social organization within the Thai nation-state. -

Culture of Abuse of Power Due to Conflict of Interest to Corruption for Too Long on the Management Form Resources of Oil and Gas in Indonesia

International Journal of Criminology and Sociology, 2020, 9, 247-254 247 Culture of Abuse of Power Due to Conflict of Interest to Corruption for Too Long on The Management form Resources of Oil and Gas in Indonesia Bambang Slamet Riyadi* Lecturer of Business Law and Criminology at the Faculty of Law, University of Nasional, Jakarta Indonesia Abstract: This research is a culture of abuse of power due to conflicts of interest so that corruption takes too long to manage oil and natural gas resources in Indonesia in managing oil and natural gas resources in Indonesia. The problem of this research is that the Indonesian state is equipped with abundant natural resources, including oil and natural gas resources. According to Article 33 of the 1945 Constitution, the oil and natural gas resources should be controlled by the state for the greatest prosperity of the people. In fact, the Indonesian people are not prosperous despite the abundance of oil and natural gas resources. Historical research methods. With the concept of cultural criminology. The results of research since the independence of the Republic of Indonesia have occurred abuse of power due to conflicts of interest to maintain power in the management of oil and gas with corruption impacting state losses, especially the suffering of the Indonesian people for too long, so that a culture of corruption is formed. This happens first; the sudden change component, caused by global changes and the modernization of the tendency of society to comply with materialism and consumerism while ignoring the cultural values of shame in the life of the nation and state. -

115 Bab Iv Analisis Prinsip Kewartawanan Mochtar

BAB IV ANALISIS PRINSIP KEWARTAWANAN MOCHTAR LUBIS DALAM BUKU MOCHTAR LUBIS WARTAWAN JIHAD DITINJAU DARI PERSPEKTIF KOMUNIKASI ISLAM A. Seleksi Teks Peneliti memilih buku Mochtar Lubis Wartawan Jihad karena menurut penulis buku tersebut memuat pandangan banyak orang tentang kewartawanan Mochtar Lubis ketika menjadi pemimpin redaksi surat kabar Indonesia Raya. Peneliti menyeleksi teks yang menggambarkan prinsip kewartawanan Mochtar Lubis dari bagian 3, bagian 1 dan 2 buku Mochtar Lubis Wartawan Jihad. Bagian 3 berisi tulisan Mochtar Lubis sendiri (yang kemudian dikutip dalam buku ini), yang lebih tepat dianalisis pertama kali, diikuti dengan bagian 1 dan bagian 2 buku, karena kedua bagian tersebut berisi pendapat orang lain tentang Mochtar Lubis. Bagian 1 dan bagian 2 buku dapat menjadi bukti apakah Mochtar Lubis menjalankan sendiri prinsip kewartawanan yang ia tulis. 115 116 B. Unit Analisis dan Kategori Isi Peneliti membaca seluruh isi buku Mochtar Lubis Wartawan Jihad dan menjadikan kalimat/paragraf yang menggambarkan prinsip kewartawanan Mochtar Lubis sebagai unit analisis. Tabel 3. Analisis Prinsip Kewartawanan Mochtar Lubis N Kategori Unit Analisis o a B c d e f 1. Etos pers Indonesia bersumber pada perjuangan Bangsa Indonesia untuk V memajukan bangsa dan memerdekaan bangsa dari telapak kaki penjajah (hlm. 460) 2. Mengangkat pena melawan V penyelewengan kekuasaan (hlm. 467) 3. Memberitakan penyelewengan, meskipun pelakunya V teman sendiri. (hlm. 468) 4. Kritik dalam pers adalah sumbangan pikiran V untuk membangun bangsa (hlm. 473) 5. Wartawan jihad, V wartawan yang 117 membongkar hal bobrok dalam pemerintahan. (hlm. 11) 6. Lebih baik mati daripada tidak bisa V menjadi pers bebas (hlm. 17) 7. Surat kabar jihad, menentang korupsi, penyalahgunaan wewenang, V ketidakadilan, dan feodalisme dalam sikap manusia (hlm. -

The S. Rajaratnam Private Papers

The S. Rajaratnam Private Papers Folio No: SR.055 Folio Title: Letters, Correspondences ITEM DOCUMENT DIGITIZATION ACCESS DOCUMENT CONTENT NO DATE STATUS STATUS Reply letter to Karen Teo-Pereira re: SPH reading SR.055.001 26/11/1992 Digitized Open room Letter from Karen Teo-Pereira re: SPH reading room SR.055.002 16/11/1992 Digitized Open with attached visual of plaque Reply letter to Gopika Gopalakrishnan re: Sunday SR.055.003 30/11/1992 Digitized Open Morning Singapore - Celebrity Chef Letter from Gopika Gopalakrishnan re: Sunday SR.055.004 25/11/1992 Digitized Open Morning Singapore - Celebrity Chef Letter from John Robertson re: Invitation to Cameron SR.055.005 27/11/1992 Digitized Open Mackintosh's production of Les Miserables Letter from The Peranakan Association on invitation SR.055.006 25/9/1992 to its 92nd anniversary dinner on 13 November 1992 Digitized Open with attached Christopher Sim Cher Kwang name card Letter from Singapore International Foundation re: SR.055.007 28/10/1992 Digitized Open Visit of ACM Siddhi Savetsila Letter from Embassy of the United States of America on invitation to lunch and observation of the U.S. SR.055.008 19/10/1992 Digitized Open President Election on 4 November 1992 with enclosed article from Singapore American on "Election Central" Reply letter to Tom Fernandez re: Invitation to deliver keynote speech at the Conference on "Singapore SR.055.009 13/10/1992 Digitized Open attaining developed nation status. Why you must act now!" 1 of 17 The S. Rajaratnam Private Papers ITEM DOCUMENT DIGITIZATION ACCESS DOCUMENT CONTENT NO DATE STATUS STATUS Letter from Tom Fernandez re: Invitation to deliver keynote speech at the Conference on "Singapore SR.055.010 12/10/1992 Digitized Open attaining developed nation status. -

ASEAS 2(1) 2009 Österreichische Zeitschrift Für Südostasienwissenschaften Austrian Journal of South-East Asian Studies ASEAS 2 (1)

ASEAS 2(1) 2009 Österreichische Zeitschrift für Südostasienwissenschaften Austrian Journal of South-East Asian Studies ASEAS 2 (1) ASEAS Österreichische Zeitschrift für Südostasienwissenschaften, 2 (1), 2009 Austrian Journal of South-East Asian Studies, 2 (1), 2009 Herausgeber / Publisher SEAS Gesellschaft für Südostasienwissenschaften / Society for South-East Asian Studies Stumpergasse 39/22, 1060 Wien, Austria ZVR Zahl 786121796 www.SEAS.at Chefredakteur / Editor-in-chief Alfred Gerstl Redaktion / Editing Board Christian Bothe, Belinda Helmke, Erwin Schweitzer, Christian Wawrinec Wissenschaftlicher Beirat / Advisory Board Karl Husa, Harold R. Kerbo, Rüdiger Korff, Susanne Schröter Redaktionsanschrift / Editorial Office Adress ASEAS, Stumpergasse 39/22, 1060 Wien, Austria [email protected] Titelfoto / Cover Photo Margit Haider Layout Christian Bothe Zum Zitieren nutzen Sie bitte / For citing please use Autor: Titel, ASEAS - Österreichische Zeitschrift für Südostasienwissenschaften, 2 (1), 2009 Author: Title, ASEAS - Austrian Journal of South-East Asian Studies, 2 (1), 2009 ISSN 1999-2521 (Print), ISSN 1999-253X (Online) Wien / Vienna 2009 © SEAS Gesellschaft für Südostasienwissenschaften / Society for South-East Asian Studies. Mehr Informationen finden Sie unter www.SEAS.at. Please find further information at www.SEAS.at. Inhalt / Contents 01 Editorial Belinda Helmke & Christian Wawrinec Aktuelle Südostasienforschung / Current Research on South-East Asia 06 Nachbarschaftsstreit am Mekong: König Anuvong und die Geschichte der prekären Lao-Thai-Beziehungen -

Adultery in Mochtar Lubis' Novel Senja Di Jakarta

Proceedings of the 1st Annual International Conference on Language and Literature, 18-19 April 2018, Fakultas Sastra, UISU, Medan, Indonesia. ADULTERY IN MOCHTAR LUBIS’ NOVEL SENJA DI JAKARTA Raja Fauziah, Efendi Barus, M. Ali Pawiro Master’s Program, Fakultas Sastra, Universitas Islam Sumatera Utara, Medan, Indonesia Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstact The research is concerned with types of adultery based on the plot giving pictures of immoral behavior of some of the major characters committing adultery. Some of them are married, and some are not. They are brave and not ashamed of doing this immoral deed because they are not close to the doctrine of their own religion that prohibits them doing this shameful behavior. They do not even seem to be afraid of doing something which is regarded as a very sinful deed. Adultery is a sexual relationship in which a man or women has with another partner rather than his/her own spouse. Adultery is seen as a great sin in the society. Adultery maliciously interferes with marriage relations, and sometimes opens the door to divorce. (Dillon, 2016). The research is conducted using descriptive qualitative method designed to obtain information which is concerned with the current status of phenomena that occur naturally. (Ary, 1972). The results show that there are three types of adultery committed by the major characters: Visual, Mental and Physical Adulteries. Key words: adultery, visualization, mental, physics Introduction This study is concerned with adultery which is found in the novel Senja di Jakarta written by the Indonesian writer, Mochtar Lubis, and published in 1981. -

Images of Japanese Men in Post-Colonial Philippine Literature and Films

3937 UNIVERSITY OF HAWNI LIBRARY Images of Japanese Men in Post-Colonial Philippine Literature and Films A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I IN P ARTIALFULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ASIAN STUDIES AUGUST 2007 By AkikoMori Thesis Committee: Barbara Andaya, Chairperson Ruth Mabanglo Miriam Sharma We' certify that we have read this thesis and that, in our opinion, it is satisfactory in scope and quality as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in Asian Studies. THESIS COMMITTEE ($~~~ • ~~ ,. HAWN CB5 .H3 no. 3437 • 11 Mori Contents Map 3 Preface 4 1. Japan-Philippine Relations: A Historical Overview 9 2. Setting the Stage Images of Japanese Men in Post-Colonial Filipino Literature 16 3. Sources: An Interview, Novels, Short Stories and Films Interview with F. Sionil Jose 20 Filipino Sources: Novels and Short Stories 28 Filipino Sources: Films 32 Japanese Sources: Two Novels 34 4. The Images of Japanese Men Brutal Soldiers 35 Depictions of Brutality 42 Why Brutality? Two Japanese Novels 47 Non-Soldiers: Businessmen and Lovers 59 5. Analysis 68 Conclusion 77 2 Mori ....... 1IIands 124 Philippines . alaco 200km, 150m Trace MIu1Ii'flS" ' ~=- u.mb}1140 . -- DIInagI~ -- But • Cagayan Qo • . • Mala eo Mtlrawl T . lag Cotabalo va • , tl854t1lO _ 3 Mori PREFACE My interest in the Philippines and its literature and films began seriously in 2000 when, as a freshman at the University of Hawaii at Manoa, I took Tagalog 101 and a couple of Filipino related courses offered by the Asian Studies program, the Filipino Programs and the Indo Pacific Language and Literature program.