Revolutionary War at Sea Traveling Trunk Lessons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1St New York Volunteer Infantry (Tenth Battalion) Spanish American

1st NY Volunteer Infantry "10th New York National Guard" In the Spanish American War THE 1st New York Volunteer Infantry (Tenth Battalion) IN THE Spanish American War 1898 - 1900 COMPILED BY COL Michael J. Stenzel Bn Cdr 210th Armor March 1992 - September 1993 Historian 210th Armor Association 1st NY Volunteer Infantry "10th New York National Guard" In the Spanish American War 1st NY Volunteer Infantry in the Spanish American War 1898-1900 HE latter part of the eighteenth century beheld Spain the proud mistress of a domain upon which she could boast that the sun never set. At the close of the nineteenth hardly a vestige of that great empire remained. In 1898 its possessions had dwindled down to the Islands of Cuba and Porto Rico. A rebellion by the people of Cuba against the rule of Spain had been going on for several years. Governor General Weyler, who represented the Spanish Crown, through the methods he used in trying to put down the rebellion, turned the sympathies of the people of the United States toward the cause of the Cuban revolutionist. "Butcher" Weyler, as he was called, was soundly denounced in this country. While the United States government maintained a "hands off" policy as between Spain and the Cubans, it kept the battleship "Maine" in Havana harbor to be on hand in case of danger to Americans. On February 15, 1398, the "Maine" was blown up and 260 members of her crew killed. Spain was blamed for the destruction of the battleship and the people of the United States became inflamed over the outrage and demanded action be taken to put an end to the trouble in Cuba. -

The American Navies and the Winning of Independence

The American Navies and the Winning of Independence During the American War of Independence the navies of France and Spain challenged Great Britain on the world’s oceans. Combined, the men-o-war of the allied Bourbon monarchies outnumbered those of the British, and the allied fleets were strong enough to battle Royal Navy fleets in direct engagements, even to attempt invasions of the British isles. In contrast, the naval forces of the United States were too few, weak, and scattered to confront the Royal Navy head on. The few encounters between American and British naval forces of any scale ended in disaster for the Revolutionary cause. The Patriot attempt to hold the Delaware River after the British capture of Philadelphia in 1777, however gallant, resulted in the annihilation of the Pennsylvania Navy and the capture or burning of three Continental Navy frigates. The expedition to recapture Castine, Maine, from the British in 1779 led to the destruction of all the Continental and Massachusetts Navy ships, American privateers, and American transports involved, more than thirty vessels. And the fall of Charleston, South Carolina, to the British in 1780 brought with it the destruction or capture of four Continental Navy warships and several ships of the South Carolina Navy. Despite their comparative weakness, American naval forces made significant contributions to the overall war effort. Continental Navy vessels transported diplomats and money safely between Europe and America, convoyed shipments of munitions, engaged the Royal Navy in single ship actions, launched raids against British settlements in the Bahamas, aggravated diplomatic tensions between Great Britain and European powers, and carried the war into British home waters and even onto the shores of England and Scotland. -

“What Are Marines For?” the United States Marine Corps

“WHAT ARE MARINES FOR?” THE UNITED STATES MARINE CORPS IN THE CIVIL WAR ERA A Dissertation by MICHAEL EDWARD KRIVDO Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2011 Major Subject: History “What Are Marines For?” The United States Marine Corps in the Civil War Era Copyright 2011 Michael Edward Krivdo “WHAT ARE MARINES FOR?” THE UNITED STATES MARINE CORPS IN THE CIVIL WAR ERA A Dissertation by MICHAEL EDWARD KRIVDO Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved by: Chair of Committee, Joseph G. Dawson, III Committee Members, R. J. Q. Adams James C. Bradford Peter J. Hugill David Vaught Head of Department, Walter L. Buenger May 2011 Major Subject: History iii ABSTRACT “What Are Marines For?” The United States Marine Corps in the Civil War Era. (May 2011) Michael E. Krivdo, B.A., Texas A&M University; M.A., Texas A&M University Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. Joseph G. Dawson, III This dissertation provides analysis on several areas of study related to the history of the United States Marine Corps in the Civil War Era. One element scrutinizes the efforts of Commandant Archibald Henderson to transform the Corps into a more nimble and professional organization. Henderson's initiatives are placed within the framework of the several fundamental changes that the U.S. Navy was undergoing as it worked to experiment with, acquire, and incorporate new naval technologies into its own operational concept. -

The Navy Turns 245

The Navy Turns 245 "A good Navy is not a provocation to war. It is the surest guaranty of peace." - Theodore Roosevelt "I can imagine no more rewarding a career. And any man who may be asked in this century what he did to make his life worthwhile, I think can respond with a good deal of pride and satisfaction: 'I served in the United States Navy.'" - John F. Kennedy October 13 marks the birthday of the U.S. Navy, which traces its roots back to the early days of the American Revolution. On October 13, 1775, the Continental Congress established a naval force, hoping that a small fleet of privateers could attack British commerce and offset British sea power. The early Continental navy was designed to work with privateers to wage tactical raids against the transports that supplied British forces in North America. To accomplish this mission the Continental Congress purchased, converted, and constructed a fleet of small ships -- frigates, brigs, sloops, and schooners. These navy ships sailed independently or in pairs, hunting British commerce ships and transports. Two years after the end of the war, the money-poor Congress sold off the last ship of the Continental navy, the frigate Alliance. But with the expansion of trade and shipping in the 1790s, the possibility of attacks of European powers and pirates increased, and in March 1794 Congress responded by calling for the construction of a half-dozen frigates, The United States Navy was here to stay With thousands of ships and aircraft serving worldwide, the U.S. Navy is a force to be reckoned with. -

The Ambiguous Patriotism of Jack Tar in the American Revolution Paul A

Loyalty and Liberty: The Ambiguous Patriotism of Jack Tar in the American Revolution Paul A. Gilje University of Oklahoma What motivated JackTar in the American Revolution? An examination of American sailors both on ships and as prisoners of war demonstrates that the seamen who served aboard American vessels during the revolution fit neither a romanticized notion of class consciousness nor the ideal of a patriot minute man gone to sea to defend a new nation.' While a sailor could express ideas about liberty and nationalism that matched George Washington and Ben Franklin in zeal and commitment, a mixxture of concerns and loyalties often interceded. For many sailors the issue was seldom simply a question of loyalty and liberty. Some men shifted their position to suit the situation; others ex- pressed a variety of motives almost simultaneously. Sailors could have stronger attachments to shipmates or to a hometown, than to ideas or to a country. They might also have mercenary motives. Most just struggled to survive in a tumultuous age of revolution and change. Jack Tar, it turns out, had his own agenda, which might hold steadfast amid the most turbulent gale, or alter course following the slightest shift of a breeze.2 In tracing the sailor's path in these varying winds we will find that seamen do not quite fit the mold cast by Jesse Lemisch in his path breaking essays on the "inarticulate" Jack Tar in the American Revolution. Lemisch argued that the sailor had a concern for "liberty and right" that led to a "complex aware- ness that certain values larger than himself exist and that he is the victim not only of cruelty and hardship but also, in the light of those values, of injus- tice."3 Instead, we will discover that sailors had much in common with their land based brethren described by the new military historians. -

Appendix As Too Inclusive

Color profile: Disabled Composite Default screen Appendix I A Chronological List of Cases Involving the Landing of United States Forces to Protect the Lives and Property of Nationals Abroad Prior to World War II* This Appendix contains a chronological list of pre-World War II cases in which the United States landed troops in foreign countries to pro- tect the lives and property of its nationals.1 Inclusion of a case does not nec- essarily imply that the exercise of forcible self-help was motivated solely, or even primarily, out of concern for US nationals.2 In many instances there is room for disagreement as to what motive predominated, but in all cases in- cluded herein the US forces involved afforded some measure of protection to US nationals or their property. The cases are listed according to the date of the first use of US forces. A case is included only where there was an actual physical landing to protect nationals who were the subject of, or were threatened by, immediate or po- tential danger. Thus, for example, cases involving the landing of troops to punish past transgressions, or for the ostensible purpose of protecting na- tionals at some remote time in the future, have been omitted. While an ef- fort to isolate individual fact situations has been made, there are a good number of situations involving multiple landings closely related in time or context which, for the sake of convenience, have been treated herein as sin- gle episodes. The list of cases is based primarily upon the sources cited following this paragraph. -

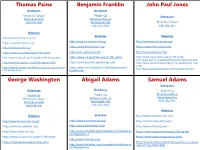

Benjamin Franklin John Paul Jones Databases Databases

Thomas Paine Benjamin Franklin John Paul Jones Databases Databases Britannica School Pebble-Go Databases Word Book Kids Britannica School Kids Info. Bits Word Book Kids Britannica School Kids Info. Bits Kids Info. Bits Websites Websites Websites http://www.mountvernon.org/ http://www.mountvernon.org/ http://www.mountvernon.org/ https://www.historyisfun.org/ http://www.ushistory.org/ https://www.historyisfun.org/ https://www.historyisfun.org/ https://www.cia.gov/kids-page/k-5th-grade http://www.ushistory.org/ http://www.ushistory.org/ http://www.let.rug.nl/usa/biographies/thomas-paine/ https://www.cia.gov/kids-page/k-5th-grade https://www.cia.gov/kids-page/k-5th-grade http://www.navy.mil/navydata/traditions/html/jpjones.html http://www.historyguide.org/intellect/paine.html https://www.bostonteapartyship.com/ https://www.nps.gov/revwar/about_the_revolution/jp_jone s.html http://www.ducksters.com/history/american_revolution/t https://www.fi.edu/benjamin-franklin/benjamin- http://www.eyewitnesstohistory.com/johnpauljones.htm homas_paine.php franklin-faq George Washington Abigail Adams Samuel Adams Databases Databases Databases Pebble-Go Pebble-Go Pebble-Go Britannica School Britannica School Britannica School Word Book Kids Word Book Kids Word Book Kids Kids Info. Bits Kids Info. Bits Kids Info. Bits Websites Websites Websites http://www.mountvernon.org/ http://www.mountvernon.org/ http://www.mountvernon.org/ https://www.historyisfun.org/ https://www.historyisfun.org/ https://www.historyisfun.org/ http://www.ushistory.org/ http://www.ushistory.org/ -

A Fitting Tribute to America's Soldiers and Sailors'

Cllj Volume 4, Issue 5 July-August 1998 I A Newsletter for the Supporters of the Hampton Roads Naval Museum I "A Fitting Tribute to America's Soldiers and Sailors'' Hampton Roads' Spanish-American War Victory Parade by Becky Poulliot orfolk's bid for a naval ship to instill patriotism, increase N tourism and prime the local economy predates the battleship Wisconsin by almost a century. On May 29, 1899 thousands on both sides of the Elizabeth River witnessed a massive parade of ships honoring the arrival of the newest addition to the 1 OOth Anniversary The Spanish-American War 1898-1998 fleet, the Reina Mercedes. Reina's story-and how she came to Hampton Roads-has all the makings of a suspense novel, with happenstance and The Virginian-Pilot produced and published this drawing ofthe Spanish unprotected cruiser Reina Mercedes in 1899. Captured and successfully salvaged in late 1898 by the U.S. Navy, the cruiser politics determining the final outcome. was an obsolete ship and had lillie combat value, even to the Spanish. Her arrival in Hampton The Reina Mercedes began her Roads, however, sparked a large parade to celebrate America 's decisive victory over the Spanish. career in 1887 as a Spanish unprotected (May 6, 1899 drawing from theVirginian-PiloV cruiser. Named for the recently under steam or sail. She and two sister insurrectionists. With the outbreak of deceased Queen Mercedes and rigged ships, Alfonso XII and Reina Cristina, the war the Spanish fleet needed every as a schooner, Reina like its early were designed by the Spanish Brigadier vessel, no matter how dilapidated. -

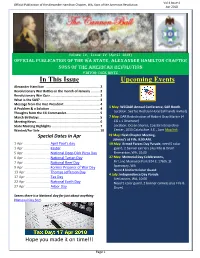

In This Issue Upcoming Events Alexander Hamilton

Vol 4 Issue 4 Official Publication of the Alexander Hamilton Chapter, WA, Sons of the American Revolution Apr 2018 Volume IV, Issue IV (April 2018) Official Publication of the WA State, Alexander Hamilton Chapter Sons of the American Revolution Editor: dick motz In This Issue Upcoming Events Alexander Hamilton ....................................................... 2 Revolutionary War Battles in the month of January ......... 2 Revolutionary War Quiz .................................................. 2 What is the SAR? ............................................................. 3 Message from the Vice President ..................................... 4 A Problem & a Solution ................................................... 4 5 May: WSSDAR Annual Conference, SAR Booth. Thoughts from the CG Commander .................................. 5 Location: SeaTac Red Lion Hotel (all hands invited) March Birthdays .............................................................. 5 7 May: DAR Rededication of Robert Gray Marker (4 Meeting News ................................................................. 6 CG + 1 Drummer) State Meeting Highlights ................................................. 7 Location: Ocean Shores, Coastal Interpretive Wanted/For Sale ............................................................. 10 Center, 1033 Catala Ave. S.E., 1pm Map link Special Dates in Apr 19 May: Next Chapter Meeting, Johnny’s at Fife, 9:00 AM. 1 Apr ........................... April Fool’s day 19 May: Armed Forces Day Parade, need 5 color 1 Apr .......................... -

Chapter 3 Study Guide 1

CHAPTER 3 STUDY GUIDE 1. How did Thomas Jefferson feel about breaking away from Great Britain? 2. This person contributed money to the Patriot cause and served in the Continental Army? 3. What battle was the turning point of the American Revolution? 4. What big statement is Thomas Jefferson known for saying? 5. What challenges did the Patriots face at sea? 6. What effect did “Common Sense” have on the colonial leaders? 7. What event happened to allow the Patriots to win at Yorktown? 8. What happened at the Battle of Trenton that was different from the other battles? 9. What ideas developed during the Enlightenment and the Great Awakening that had influence on the colonists? 10. What jobs did women do during the American Revolution? 11. What questions about slaves did the Declaration of Independence address? 12. What setbacks did the Patriots face in the West? 13. What were the names of the foreigners (men) that came to the aid of the Patriots? 14. What word did Washington use to encourage his soldiers? 15. Where did the British make their biggest gains during the war? 16. Where was the final battle of the American Revolution? 17. Which battle occurred on Christmas night? 18. Which event led to the First Continental Congress? 19. Which was the first battle of the American Revolution? CHAPTER 3 STUDY GUIDE 20. Who as Bernardo de Gálvez? 21. Who helped the Continental Army with basic military skills? 22. Who was nicknamed, “the Swamp Fox” and why? 23. Who were the Loyalists? 24. Who were the Sons of Liberty? 25. -

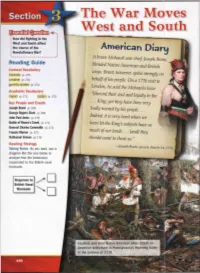

The War Moves West and Se.Uth \Lmif1ml~

The War Moves West and Se.uth \lmif1Ml~ ..... ..: : How did fighting in the : West and South affect : the course of the American Diar!1 : Revolutionary War? . .. .. .. A brave Mohawk war chief Joseph Brant, Reading Guide blended Native American and British Content Vocabulary blockade (p. 170) ways. Brant however, spoke strongly on privateer (p. 170) behalf ofhis people. On a 1776 visit to guerrilla warfare (p. 172) London, he said the Mohawks have Academic Vocabulary impact (p. 171) sustain (p. 173) "[shown] their zeal and loyalty to the Key People and Events ... King; yet they have been very Joseph Brant (p. 169) badly treated by his people . ... George Rogers Clark (p. 169) John Paul Jones (p. 170) Indeed, it is very hard when we Battle of Moore's Creek (p. 171) have let the King's subjects have so General Charles Cornwallis (p. 171) Francis Marion (p. 172) much ofour lands ... [and] they Nathanael Greene (p. 173) should want to cheat us." Reading Strategy Taking Notes As you read, use a -joseph Brant, speech, March 14, 1776 diagram like the one below to analyze how the Americans responded to the British naval blockade. Response to British Naval Blockade War in the West Henry Hamilton, British commander at Detroit, was called the "hair buyer." He l ~ mtjlm¥1 The British, along with their Native earned this nickname because he paid Native American allies, led attacks against settlers in the Americans for settlers' scalps. West. Victory at Vincennes History and You Do you have a nickname? If so, how did you get it? Read to learn the nickname of George Rogers Clark, a lieutenant colo Henry Hamilton, the British commander at Detroit. -

Rofworld •WKR II

'^"'^^«^.;^c_x rOFWORLD •WKR II itliiro>iiiiii|r«trMit^i^'it-ri>i«fiinit(i*<j|yM«.<'i|*.*>' mk a ^. N. WESTWOOD nCHTING C1TTDC or WORLD World War II was the last of the great naval wars, the culmination of a century of warship development in which steam, steel and finally aviation had been adapted for naval use. The battles, both big and small, of this war are well known, and the names of some of the ships which fought them are still familiar, names like Bismarck, Warspite and Enterprise. This book presents these celebrated fighting ships, detailing both their war- time careers and their design features. In addition it describes the evolution between the wars of the various ship types : how their designers sought to make compromises to satisfy the require - ments of fighting qualities, sea -going capability, expense, and those of the different naval treaties. Thanks to the research of devoted ship enthusiasts, to the opening of government archives, and the publication of certain memoirs, it is now possible to evaluate World War II warships more perceptively and more accurately than in the first postwar decades. The reader will find, for example, how ships in wartime con- ditions did or did not justify the expecta- tions of their designers, admiralties and taxpayers (though their crews usually had a shrewd idea right from the start of the good and bad qualities of their ships). With its tables and chronology, this book also serves as both a summary of the war at sea and a record of almost all the major vessels involved in it.