Tourism Development in Okinawa: Spatial and Temporal Patterns

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Agricultural Environment of the Back Land of Nagura Bay, Okinawa Prefecture"

"Agricultural Environment of the Back Land of Nagura Bay, Okinawa Prefecture" 著者 "KATAYAMA Tadao C., SHINAGAWA Akio, HIGASHI Teruo" journal or 南海研紀要 publication title volume 6 number 1 page range 37-55 URL http://hdl.handle.net/10232/15660 Mem. Kagoshima Univ. Res. Center S. Pac. Vol.6, No. 1, 1985 37 Agricultural Environment of the Back Land of Nagura Bay, Okinawa Prefecture* Tadao C. Katayama**, Akio Shinagawa*** and Teruo Higashi*** Abstract The agricultural environment of the back land of Nagura Bay, Ishigaki Island, Okinawa Prefecture, /'. e., upland factors and cropping systems were discussed on the basis of references and observation in the area. There is a rapid consumption and a high turnover rate for organic matter, nutrients, minerals. To improve soil preserva tion, it is recommended utilization of natural topographical features and plants is more suitable than building artificial structures. Plants with a tap root and deep-rooted trees are good examples of natural stabilization structures. In comparison to the agricultural practices dominated by hand labor and small machines, procedures utilizing large machines are disadvantageous, because they increase the amount of times the land remains bare and they reduce the necessary elasticity in farm practices. It is recom mended to increase the agricultural development cautiously to preserve the environ ment and to keep the local population consensus. Introduction Ishigaki Island lies between 124°04'E and 124°20'E longitude and 24°19'N and 24° 36'N latitude (Fig. 1). In general, Ishigaki Island is said to be characteristic of a sub-tropical region. Because of its sub-tropical nature, it has higher temperatures and more abundant solar energy in comparison with Japan proper. -

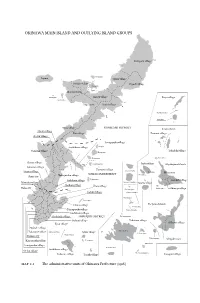

Okinawa Main Island and Outlying Island Groups

OKINAWA MAIN ISLAND AND OUTLYING ISLAND GROUPS Kunigami village Kourijima Iejima Ōgimi village Nakijin village Higashi village Yagajijima Ōjima Motobu town Minnajima Haneji village Iheya village Sesokojima Nago town Kushi village Gushikawajima Izenajima Onna village KUNIGAMI DISTRICT Kerama Islands Misato village Kin village Zamami village Goeku village Yonagusuku village Gushikawa village Ikeijima Yomitan village Miyagijima Tokashiki village Henzajima Ikemajima Chatan village Hamahigajima Irabu village Miyakojima Islands Ginowan village Katsuren village Kita Daitōjima Urasoe village Irabujima Hirara town NAKAGAMI DISTRICT Simojijima Shuri city Nakagusuku village Nishihara village Tsukenjima Gusukube village Mawashi village Minami Daitōjima Tarama village Haebaru village Ōzato village Kurimajima Naha city Oki Daitōjima Shimoji village Sashiki village Okinotorishima Uozurijima Kudakajima Chinen village Yaeyama Islands Kubajima Tamagusuku village Tono shirojima Gushikami village Kochinda village SHIMAJIRI DISTRICT Hatomamajima Mabuni village Taketomi village Kyan village Oōhama village Makabe village Iriomotejima Kumetorishima Takamine village Aguni village Kohamajima Kume Island Itoman city Taketomijima Ishigaki town Kanegusuku village Torishima Kuroshima Tomigusuku village Haterumajima Gushikawa village Oroku village Aragusukujima Nakazato village Tonaki village Yonaguni village Map 2.1 The administrative units of Okinawa Prefecture (1916) <UN> Chapter 2 The Okinawan War and the Comfort Stations: An Overview (1944–45) The sudden expansion -

Practical and Advanced Renewable Energy in Okinawa

The First International Workshop on Open Energy Systems (14-15 January 2014, OIST) Practical and Advanced Renewable Energy in Okinawa Dr. Jun-ichiro Giorgos TSUTSUMI Professor, Faculty of Engineering E-mail: [email protected] Contents of Presentation • Emission of Green House Gas from Energy • Ordinary Popular Natural Energy in Okinawa – Natural Energy (Photovoltaic System, Wind Turbine) – Recycle Energy (Waste Heat, Digested Gas, BDF) • Hawaii-Okinawa Clean Energy Partnership – Smart Grid System, OTEC, Energy Saving, People Exchange • Energy Research in University of the Ryukyus – Remote Control, Ocean Biomass, Solar Heater, Power Stabilizer • Smart Energy Projects by Okinawa Prefecture – Smart Energy Houses, Leveling System, Miyako Projects, etc. • Energy Projects in Miyako Island – Whole Island EMS, PV on Rented Roofs, Small EV • Remarks in Development of Renewable Energy Global Air Temperature and CO2 Concentration Industrial Revolu0on CO2 Emission Rate from Fossil Fuels Heating values and CO2 emission rates by combustion of various fossil fuels. CO2 emission: Coal > Oil > Gas. CO2 Emission Rate by Electric Power Companies before Fukushima “Adjusted rate” means the emission rates adjusted by the carbon credits of Kyoto mechanism. Mega Solar Fields in Okinawa (1) Fukuzato, Miyakojima (4,000kW) Okinawa Electric Power Co. (2) Abu, Nago (1,000kW) Okinawa Electric Co. (3) Ikehara, Okinawa (2,000kW) EcoLumiere LLC. Mega Solar Energy Field in Miyako Island Damages on wind turbines By typhoon 0314 (Maemi) New Type of Tiltable Wind -

Effects of Constructing a New Airport on Ishigaki Island

Island Sustainability II 181 Effects of constructing a new airport on Ishigaki Island Y. Maeno1, H. Gotoh1, M. Takezawa1 & T. Satoh2 1Nihon University, Japan 2Nihon Harbor Consultants Ltd., Japan Abstract Okinawa Prefecture marked the 40th anniversary of its reversion to Japanese sovereignty from US control in 2012. Such isolated islands are almost under the environment separated by the mainland and the sea, so that they have the economic differences from the mainland and some policies for being active isolated islands are taken. It is necessary to promote economical measures in order to increase the prosperity of isolated islands through initiatives involving tourism, fisheries, manufacturing, etc. In this study, Ishigaki Island was considered as an example of such an isolated island. Ishigaki Island is located to the west of the main islands of Okinawa and the second-largest island of the Yaeyama Island group. Ishigaki Island falls under the jurisdiction of Okinawa Prefecture, Japan’s southernmost prefecture, which is situated approximately half-way between Kyushu and Taiwan. Both islands belong to the Ryukyu Archipelago, which consists of more than 100 islands extending over an area of 1,000 km from Kyushu (the southwesternmost of Japan’s four main islands) to Taiwan in the south. Located between China and mainland Japan, Ishigaki Island has been culturally influenced by both countries. Much of the island and the surrounding ocean are protected as part of Iriomote-Ishigaki National Park. Ishigaki Airport, built in 1943, is the largest airport in the Yaeyama Island group. The runway and air security facilities were improved in accordance with passenger demand for larger aircraft, and the airport became a tentative jet airport in May 1979. -

Genetic Lineage of the Amami Islanders Inferred from Classical Genetic Markers

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.04.18.440379; this version posted April 19, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Genetic lineage of the Amami islanders inferred from classical genetic markers Yuri Nishikawa and Takafumi Ishida Department of Biological Sciences, Graduate School of Science, The University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan Correspondence: Yuri Nishikawa, Department of Biological Sciences, Graduate School of Science, The University of Tokyo, Hongo 7-3-1, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 113-0033, Japan. E-mail address: [email protected] 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.04.18.440379; this version posted April 19, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Abstract The peopling of mainland Japan and Okinawa has been gradually unveiled in the recent years, but previous anthropological studies dealing people in the Amami islands, located between mainland Japan and Okinawa, were less informative because of the lack of genetic data. In this study, we collected DNAs from 104 subjects in two of the Amami islands, Amami-Oshima island and Kikai island, and analyzed the D-loop region of mtDNA, four Y-STRs and four autosomal nonsynonymous SNPs to clarify the genetic structure of the Amami islanders comparing with peoples in Okinawa, mainland Japan and other regions in East Asia. -

Local Dishes Loved by the Nation

Sapporo 1 Hakodate 2 Japan 5 3 Niigata 6 4 Kanazawa 15 7 Sendai Kyoto 17 16 Kobe 10 9 18 20 31 11 8 ocal dishes Hiroshima 32 21 33 28 26 19 13 Fukuoka 34 25 12 35 23 22 14 40 37 27 24 29 Tokyo loved by 41 38 36 Nagoya 42 44 39 30 Shizuoka Yokohama 43 45 Osaka Nagasaki 46 Kochi the nation Kumamoto ■ Hokkaido ■ Tohoku Kagoshima L ■ Kanto ■ Chubu ■ Kansai 47 ■ Chugoku ■ Shikoku Naha ■ Kyushu ■ Okinawa 1 Hokkaido 17 Ishikawa Prefecture 33 Okayama Prefecture 2 Aomori Prefecture 18 Fukui Prefecture 34 Hiroshima Prefecture 3 Iwate Prefecture 19 Yamanashi Prefecture 35 Yamaguchi Prefecture 4 Miyagi Prefecture 20 Nagano Prefecture 36 Tokushima Prefecture 5 Akita Prefecture 21 Gifu Prefecture 37 Kagawa Prefecture 6 Yamagata Prefecture 22 Shizuoka Prefecture 38 Ehime Prefecture 7 Fukushima Prefecture 23 Aichi Prefecture 39 Kochi Prefecture 8 Ibaraki Prefecture 24 Mie Prefecture 40 Fukuoka Prefecture 9 Tochigi Prefecture 25 Shiga Prefecture 41 Saga Prefecture 10 Gunma Prefecture 26 Kyoto Prefecture 42 Nagasaki Prefecture 11 Saitama Prefecture 27 Osaka Prefecture 43 Kumamoto Prefecture 12 Chiba Prefecture 28 Hyogo Prefecture 44 Oita Prefecture 13 Tokyo 29 Nara Prefecture 45 Miyazaki Prefecture 14 Kanagawa Prefecture 30 Wakayama Prefecture 46 Kagoshima Prefecture 15 Niigata Prefecture 31 Tottori Prefecture 47 Okinawa Prefecture 16 Toyama Prefecture 32 Shimane Prefecture Local dishes loved by the nation Hokkaido Map No.1 Northern delights Iwate Map No.3 Cool noodles Hokkaido Rice bowl with Tohoku Uni-ikura-don sea urchin and Morioka Reimen Chilled noodles -

Nansei Islands Biological Diversity Evaluation Project Report 1 Chapter 1

Introduction WWF Japan’s involvement with the Nansei Islands can be traced back to a request in 1982 by Prince Phillip, Duke of Edinburgh. The “World Conservation Strategy”, which was drafted at the time through a collaborative effort by the WWF’s network, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), posed the notion that the problems affecting environments were problems that had global implications. Furthermore, the findings presented offered information on precious environments extant throughout the globe and where they were distributed, thereby providing an impetus for people to think about issues relevant to humankind’s harmonious existence with the rest of nature. One of the precious natural environments for Japan given in the “World Conservation Strategy” was the Nansei Islands. The Duke of Edinburgh, who was the President of the WWF at the time (now President Emeritus), naturally sought to promote acts of conservation by those who could see them through most effectively, i.e. pertinent conservation parties in the area, a mandate which naturally fell on the shoulders of WWF Japan with regard to nature conservation activities concerning the Nansei Islands. This marked the beginning of the Nansei Islands initiative of WWF Japan, and ever since, WWF Japan has not only consistently performed globally-relevant environmental studies of particular areas within the Nansei Islands during the 1980’s and 1990’s, but has put pressure on the national and local governments to use the findings of those studies in public policy. Unfortunately, like many other places throughout the world, the deterioration of the natural environments in the Nansei Islands has yet to stop. -

KYUSHU GRAND TOUR September 20-30, 2014

KYUSHU GRAND TOUR September 20-30, 2014 Please join us for the a special post-conference tour of Kyushu – the third largest island of Japan. The EWCA Alumni Endowment Fund for Student Scholarships Committee has organized this tour and it starts in Okinawa the day after the EWC Alumni Conference ends and includes the major sites of the island of Kyushu. The tour concludes on September 30, 2014 in Fukuoka City. Kirishima Shrine (day 1) This tour is organized through the Waikiki Branch of H.I.S. Hawaii Photo courtesy H.I.S. Hawaii and they will donate $200 to the EWC Endowment Fund for Student Scholarships for each person who signs up for this tour. Join us on this adventure of Kyushu and support the future students of the EWC. The tour is not limited to conference participants so invite your friends to join the tour. Visit these places and more on your adventure. Kirishima Shinto Shrine, Sakurajima Island, Mt. Aso, Yufuin, Beppu, Yanagawa, Suizenji Garden, Kumamoto Castle, Unzen, Nagasaki Peace Park, Mt. Inasayama, Arita Porcelain Park, Fukuoka, Dazaifu Day 1 September 20, 2014 (Naha, Kagoshima Prefectures) Shiroyama Kanko Hotel, Kagoshima City (L,BD) We will depart Naha Airport in Okinawa and arrive at Kagoshima Airport where our guide will meet us. After lunch, we will tour Kirishima Shinto Shrine, experience shochu (Japanese distilled alcohol) and stroll through Senganen Garden, a Japanese style landscape garden with views of Sakurajima Island and Kagoshima Bay. Day 2 September 21, 2014 (Kagoshima Prefecture) Shiroyama Kanko Hotel, Kagoshima City (B,L,BD) We will tour the Museum of the Meiji Restoration to learn about the key figures from Kagoshima. -

Applying a Framework to Assess Deterrence of Gray Zone Aggression for More Information on This Publication, Visit

C O R P O R A T I O N MICHAEL J. MAZARR, JOE CHERAVITCH, JEFFREY W. HORNUNG, STEPHANIE PEZARD What Deters and Why Applying a Framework to Assess Deterrence of Gray Zone Aggression For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR3142 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-1-9774-0397-1 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © 2021 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Cover: REUTERS/Kyodo Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface This report documents research and analysis conducted as part of a project entitled What Deters and Why: North Korea and Russia, sponsored by the Office of the Deputy Chief of Staff, G-3/5/7, U.S. -

Invincible Investment Corporation

Invincible Investment Corporation Asset Management Report Fiscal Period ended June 30, 2019 (January 1, 2019 to June 30, 2019) Content Greetings from Naoki Fukuda, Executive Director of Invincible Investment Corporation and President & CEO of Consonant Investment Management Co., Ltd. Increase in Asset Size and Initiatives for Asset recycling Properties Acquired in July 2019 Asset Management Report Audited Financial Statements for the 32th Fiscal Period (from January 1, 2019 to June 30, 2019) Domestic Portfolio Map (As of August 31, 2019) Financial Conditions Overview of Unitholders/Investment Greetings from Naoki Fukuda, Executive Director of Invincible Investment Corporation and President & CEO of Consonant Investment Management Co., Ltd. We would like to take this opportunity to express our sincere gratitude to all unitholders of Invincible Investment Corporation (“INV”) for your continued support. We hereby provide you with a report on INV’s asset management and financial results for the 32nd fiscal period (covering the period from January 1, 2019 to June 30, 2019; the “Reporting Period”). During the Reporting Period, INV changed the investment structure for two overseas hotels to a direct ownership structure of the underlying assets from investments in anonymous associations on May 9, 2019. The change in ownership structure was made to adapt to an amended Act on Special Measures Concerning Taxation executed on April 1, 2019 and completely resolves the tax issue regarding conduit requirements. In June 2019, INV sold two residential assets for extremely favorable terms as a continuation of its asset recycling program. The total sale price was JPY 39.9 billion, resulting in a gain of JPY 11.1 billion. -

20210521 Nahha Ka Huia Conference

5/21/21 ~Japan Market Initiatives~ May 21, 2021 Mitsue Varley| Japan, Country Director 1 Hawaiʻi Inbound (Dec, 2019) Europe 1.35% Latin America 0.25% Asia 3.46% Other Oceania 3.55% 3.65% Total Visitor # Canada 5.27% 10.24 Million Korea︓ 2.24% Japan US West China︓ 44.86% Total Visitors 0.90% 15.39% (Japan) Taiwan︓ 0.24% US East 1.56 Million 22.22% *Source: Hawaiʻi Tourism Authority 1 5/21/21 Hawaiʻi Inbound by MMA in 2019 Japan:1.57 mil Korea: 225,000 Total︓10.24 mil Canada:540,103 Oceania: 363,551 U.S: 6.86 mil Source: Hawaiʻi Tourism Authority Hawaiʻi Visitor History 12,000,0 00 Total Visitors (All) 10,243,165 10,000,0 00 8,000,00 0 6,723,531 6,000,00 0 Total Visitors (Japan) 4,000,00 0 2,216,890 1,492,786 1,168,080 1,576,205 2,000,00 0 - 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 Total Visitors Japan 2 5/21/21 120.0% Japanese visitors profile 100.0% 34.8% 33.1% 31.7% 80.0% 41.5% 41.1% 41.9% 40.3% 41.5% 39.3% 38.2% 60.0% 40.0% 65.2% 66.9% 68.3% 58.5% 58.9% 58.2% 59.7% 58.5% 60.7% 61.8% 20.0% 0.0% 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 Repeater First-timer *Source: Hawaiʻi Tourism Authority Hawaiʻi Media Hula Magazines Hawaiʻi Media & Lifestyle Radio TV Show 3 5/21/21 Sister City Relationships City & County of State of Hawaiʻi Hawaiʻi County Kauaʻi County Maui County Honolulu 5 7 6 4 3 Fukuoka (1981) Hiroshima (1959) Oshima (1962) Suo-Oshima(1963) Hachijo (1964) Okinawa (1985) Naha (1961) Nago (1986) Moriyama (1975) Miyakojima -

Those on the Latter by Katayama (I) and Minamibuchi (I)

GENETIC STRUCTURE OF HUMAN POPULATIONS III. DIFFERENTIATION OF ABO BLOOD GROUP GENE FREQUENCIES IN SMALL AREAS OF JAPAN* MASATOSHI NEI and YOKO IMAIZUMI Division of Genetics, National Institute of Radiological Sciences, Chiba, Japan Receivedii .xii.65 1.INTRODUCTION INa previous paper (Nei and Imaizumi, 1966a) it was shown that the local differentiation of ABO and MitT blood group gene frequencies in Japan has occurred largely by genetic random drift. In that investi- gation the population of Japan was divided into 45 different sub- populations or Prefectures (administrative units of Japan) the sizes of which were mostly one to two millions. However, the size of mating groups of neighbourhoods in Wright's (1946) sense appears to be much smaller than the sub-populations employed in the paper. It is, there- fore, expected that the gene frequencies are locally differentiated even within these sub-populations. We thus examined the degree of differ- entiation of ABO blood group gene frequencies in several small areas of Japan. 2.DIFFERENTIATION WITHIN PREFECTURES Thereare two Prefectures, in which the local variation of ABO blood group gene frequencies can be analysed. One is Kagoshima Prefecture in Kyushu Island and the other Tokushima Prefecture in Shikoku Island (cf fig. i in Nei and Imaizumi, 1966a). The data on the former were collected by Ono and Takagi (1942) and Makisumi (1958), and those on the latter by Katayama (i) and Minamibuchi (i). The areas of Kagoshima and Tokushima Prefectures are 9,104 km2 and 4,143 km2 respectively, both including several neighbouring small islands. The population sizes of these two Prefectures at the time of 1960 census are 1,962,998 and 847,279 respectively.