LSA August 2015 Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

King and I Center for Performing Arts

Governors State University OPUS Open Portal to University Scholarship Center for Performing Arts Memorabilia Center for Performing Arts 5-9-1999 King and I Center for Performing Arts Follow this and additional works at: http://opus.govst.edu/cpa_memorabilia Recommended Citation Center for Performing Arts, "King and I" (1999). Center for Performing Arts Memorabilia. Book 158. http://opus.govst.edu/cpa_memorabilia/158 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Performing Arts at OPUS Open Portal to University Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Center for Performing Arts Memorabilia by an authorized administrator of OPUS Open Portal to University Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. «Jpntftl fOR PEfifORHIHCite Governors State University Present Rodgers & Hammerstein's fChe S $• Limousine courtesy of-Worth Limousine - Worth, IL &• Brunch courtesy of- Holiday Inn - Matteson, IL Bracelet courtesy of Bess Friedheim Jewelry,0rland Park, IL MATTESON The STAR University Park, IL May 9th* 1999 Governors State University KKPERfORMIIWflRTS and ACE ROYAL PAINTS present A Big League Theatricals Production Rodgers and Hammerstein's THE KING and I Music by Book and lyrics by Richard Rodgers Oscar Hammerstein II Based upon the novel Anna and the King ofSiam by Margaret Landon Original Choreography by Jerome Robbins with Lego Louis Susannah Kenton and (In alphabetical order) Luis Avila, Amanda Cheng, Elizabeth Chiang, Korina Crvelin, Isabelle Decauwert, Alexandra Dimeco, Derek Dymek, -

The Piano Duet Play-Along Series Gives You the • I Dreamed a Dream • in My Life • on My Own • Stars

1. Piano Favorites 13. Movie Hits 9 great duets: Candle in the Wind • Chopsticks • Don’t 8 film favorites: Theme from E.T. (The Extra-Terrestrial) Know Why • Edelweiss • Goodbye Yellow Brick Road • • Forrest Gump – Main Title (Feather Theme) • The Heart and Soul • Let It Be • Linus and Lucy • Your Song. Godfather (Love Theme) • The John Dunbar Theme • Moon 00290546 Book/CD Pack ............................$14.95 River • Romeo and Juliet (Love Theme) • Theme from Schindler’s List • Somewhere, My Love. 2. Movie Favorites 00290560 Book/CD Pack ...........................$14.95 8 classics: Chariots of Fire • The Entertainer • Theme from Jurassic Park • My Father’s Favorite • My Heart Will Go 14. Les Misérables On (Love Theme from Titanic) • Somewhere in Time • 8 great songs from the musical: Bring Him Home • Castle on Somewhere, My Love • Star Trek® the Motion Picture. a Cloud • Do You Hear the People Sing? • A Heart Full of Love The Piano Duet Play-Along series gives you the • I Dreamed a Dream • In My Life • On My Own • Stars. flexibility to rehearse or perform piano duets 00290547 Book/CD Pack ............................$14.95 00290561 Book/CD Pack ...........................$16.95 anytime, anywhere! Play these delightful tunes 3. Broadway for Two 10 songs from the stage: Any Dream Will Do • Blue Skies 15. God Bless America® & Other with a partner, or use the accompanying CDs • Cabaret • Climb Ev’ry Mountain • If I Loved You • Okla- to play along with either the Secondo or Primo Songs for a Better Nation homa • Ol’ Man River • On My Own • There’s No Business 8 patriotic duets: America, the Beautiful • Anchors part on your own. -

Broadway Beat

Hailey – Do you hear that beat? Baylee –It’s the sound of people entering the theater on the most famous street in the world. Brielle – Do you hear that beat? It’s the sound of dancing feet and orchestras tuning up. Lorelei – Do you hear that beat? It’s the sound of Rogers and Hammerstein, Lerner and Lowe, Webber and Rice. Jacob – It’s the sound of Stephen Sondheim and Stephen Schwartz. Kaden – It’s the sound of Oklahoma, Cats, The King and I. Elysa – It’s the sound of Wicked, and Fiddler on the Roof! Devin O. – Do you hear that beat? It’s the sound that dreams are made of. Emerson – Do you hear that beat? It’s the sound of Broadway! Amelia – And nobody can stop it!! -YOU CAN’T STOP THE BEAT – Homant Nathan – That’s right! You can’t stop the beat on Broadway! Abby – Speaking of Broadway, do you know who was known as “the father of American musical comedy?” Hayden – Why sure! That was George M. Cohan. Abby – That’s right! Do you know what the “M” stands for? Hayden – Umm. Maestro? Jason – Nope! Hayden – Mario? Jason – Hardly! Hayden – Marcello? Blaine – Not even close. George M. Cohan was a playwright, composer, entertainer, lyricist, actor, singer, dancer and producer. (takes a big breath) Hayden – Marcus? Billy – His first big hit was Little Johnny Jones, a story about an American jockey who went to England to ride his horse Yankee Doodle in the Derby. Hayden – Macaroni? Lillian – So, here is our salute to Mr. George “Michael” Cohan. -

Carl Dengler Scrapbooks

CARL DENGLER COLLECTION RUTH T. WATANABE SPECIAL COLLECTIONS SIBLEY MUSIC LIBRARY EASTMAN SCHOOL OF MUSIC UNIVERSITY OF ROCHESTER Processed by Mary J. Counts, spring 2006 and Mathew T. Colbert, fall 2007; Finding aid revised by David Peter Coppen, summer 2021 Carl Dengler and his band, at a performance at The Barn (1950): Tony Cataldo (trumpet), Carl Dengler (drums), Fred Schubert (saxophone), Ray Shiner (clarinet), Ed Gordon (bass), Gene Small (piano). Photograph from the Carl Dengler Collection, Scrapbook 3 (1950-1959). Carl Dengler and His Band, at unidentified performance (ca. 1960s). Photograph from the Carl Dengler Collection, Box 34/15. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Description of Collection . 4 Description of Series . 8 INVENTORY SUB-GROUP I: MUSIC LIBRARY Series 1: Manuscript Music . 13 Series 2: Published Sheet Music . 74 Series 3: Original Songs by Carl Dengler . 134 SUB-GROUP II: PAPERS Series 4: Photographs . 139 Series 5: Scrapbooks . 158 Series 6: Correspondence . 160 Series 7: Programs . 161 Series 8: Press Material . 161 Series 9: Association with Alec Wilder . 162 Series 10: Books . 163 Series 11: Awards . 165 Series 12: Ephemera . 165 SUB-GROUP III: SOUND RECORDINGS Series 13: Commercial Recordings . 168 Series 14: Instantaneous Discs . 170 Series 15: Magnetic Reels . 170 Series 16: Audio-cassettes . 176 3 DESCRIPTION OF COLLECTION Shelf location: M4A 1,1-7 and 2,1-8 Extent: 45 linear feet Biographical Sketch (L) Carl Dengler, 1934; (Center) Carl Dengler with Sigmund Romberg, ca. 1942; (Right) Carl Dengler, undated (ca. 1960s). Photographs from the Carl Dengler Collection, Box 34/30, 34/39, 34/11. Musician Carl Dengler—dance band leader*, teacher, composer. -

The King and I

The King and I - A Musical by composer Richard Rodgers & dramatist Oscar Hammerstein II WaCPAC Auditions - 9/21 (2 pm), 23, 24, & 26 (7 pm) Callbacks: 9/30 (7 pm) Performances dates: January 4, 5, 10, 11, & 12, 2020 This is an intergenerational musical so all ages are encouraged to audition. During the auditions, you will be asked to do a cold-read from a script for the artistic director. This means you will likely be given a short time (after you arrive for audition) to glance over a section of script and read with others also auditioning. We may have something different for young non-readers for this part. For character names, part descriptions and vocal ranges, please check this link online: https://studylib.net/doc/7223371/the-attached-character-list. For the musical part of the audition, please sing a verse and chorus of a song. We would prefer a show tune, similar in style to The King and I for those that are teens and older. For younger ones, please have them sing a familiar tune. Examples of songs that could be used: Teens and Adults: “Oh, What a Beautiful Mornin’” - Oklahoma! “Edelweiss” - The Sound of Music “Almost Like Being in Love” - Brigadoon “I Could’ve Danced All Night” - My Fair Lady Younger children: “I Whistle a Happy Tune” - The King and I “Getting to Know You” - The King and I “Do, Re, Mi” - The Sound of Music “Somewhere Out There” - An American Tail (film) Mary Had a Little Lamb Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star If you would like to be considered for a singing role, even if only ever singing in a group/ensemble in the show, you must do a singing audition. -

SINGER's MUSICAL THEATRE ANTHOLOGY Master Index, All Volumes

THE SINGER’S MUSICAL THEATRE ANTHOLOGY SERIES GUIDE AND INDEXES FOR ALL VOLUMES • Alphabetical Song Index • Alphabetical Show Index Updated September 2016 Key Accompaniment Book Only CDs Book/Audio S1 = Soprano, Volume 1 00361071 00740227 00000483 S2 = Soprano, Volume 2 00747066 00740228 00000488 S3 = Soprano, Volume 3 00740122 00740229 00000493 S4 = Soprano, Volume 4 00000393 00000397 00000497 S5 = Soprano, Volume 5 00001151 00001157 00001162 S6 = Soprano, Volume 6 00145258 00151246 00145264 ST = Soprano, Teen's Edition 00230043 00230051 00230047 S16 = Soprano, 16-Bar Audition 00230039 NA NA M1 = Mezzo-Soprano/Belter, Volume 1 00361072 00740230 00000484 M2 = Mezzo-Soprano/Belter, Volume 2 00747031 00740231 00000489 M3 = Mezzo-Soprano/Belter, Volume 3 00740123 00740232 00000494 M4 = Mezzo-Soprano/Belter, Volume 4 00000394 00000398 00000498 M5 = Mezzo-Soprano/Belter, Volume 5 00001152 00001158 00001163 M6 = Mezzo-Soprano/Belter, Volume 6 00145259 00151247 00145265 MT = Mezzo-Soprano/Belter, Teen's Edition 00230044 00230052 00230048 M16 = Mezzo-Soprano/Belter, 16-Bar Audition 00230040 NA NA T1 = Tenor, Volume 1 00361073 00740236 00000485 T2 = Tenor, Volume 2 00747032 00740237 00000490 T3 = Tenor, Volume 3 00740124 00740238 00000495 T4 = Tenor, Volume 4 00000395 00000401 00000499 T5 = Tenor, Volume 5 00001153 00001160 00001164 T6 = Tenor, Volume 6 00145260 00151248 00145266 TT = Tenor, Teen's Edition 00230045 00230053 00230049 T16 = Tenor, 16-Bar Audition 00230041 NA NA B1 = Baritone/Bass, Volume 1 00361074 00740236 00000486 B2 = Baritone/Bass, -

CHILDREN's VOCAL SONGFINDER Complete Listing of Publications

CHILDREN’S VOCAL SONGFINDER Complete Listing of Publications Alphabetically by Song Title Updated September 2017 CHILDREN'S VOCAL SONGFINDER Complete Listing of Publications PUBLICATION TITLE ITEM NUMBER COMMENTS 25 Folksongs Solos for Children 00154679 Audio of piano accompaniments included Art Songs for Children 00211617 Audio of piano accompaniments included Boy's Changing Voice, The 00121394 Audio of piano accompaniments included Boy's Songs from Musicals 00001127 Audio of performances and accompaniments included Broadway Presents! Kids' Musical Theatre Anthology 00322155 Audio of piano accompaniments included Broadway Songs for Kids 00230103 Book only Broadway Songs for Kids 00230103 Audio of piano accompaniments included Children's Sacred Solos 00740297 Audio of performances and accompaniments included Christmas Solos for Kids 00740130 Audio of performances and accompaniments included Church Solos for Kids 00740080 Audio of performances and accompaniments included Disney Collected Kids' Solos 00230066 Audio of piano accompaniments included Disney Duets for Kids 00124472 Audio of piano accompaniments included Disney Solos for Kids 00740197 Audio of performances and accompaniments included Giant Book of Children's Vocal Solos, The 00153571 Book only Girl's Songs from Musicals 00001126 Audio of performances and accompaniments included Kids' Broadway Songbook 00311609 Book only Kids' Broadway Songbook 00740316 Accompaniments only Kids' Broadway Songbook 00740149 Audio of piano accompaniments included Kids' Holiday Solos 00740206 Audio -

ƯYïïëìž 4Óéxšç

120792bk King&I 4/2/06 9:36 PM Page 2 Original Broadway Cast, 1951 Studio Recording, 1951 22. March of the Siamese Children 3:37 Music: Richard Rodgers New York Philharmonic Orchestra Lyrics: Oscar Hammerstein II 1. Overture 3:22 13. Overture 3:46 conducted by Richard Rodgers Transfers & Production: David Lennick Orchestra Al Goodman & His Orchestra Columbia CL 810, mx XLP 34520 Digital Restoration: Graham Newton 2. I Whistle A Happy Tune 2:40 14. My Lord And Master 2:36 Recorded 27 December 1954, New York Special thanks to Joe Cascone and Gertrude Lawrence Patrice Munsel with Al Goodman’s Orchestra Anthony Middleton 3. My Lord And Master 2:05 15. A Puzzlement 3:47 Doretta Morrow Robert Merrill with Henri René’s Orchestra Also available in the Naxos Broadway Musicals series … 4. Hello,Young Lovers 3:07 16. I Have Dreamed 3:32 Gertrude Lawrence Tony Martin & Patrice Munsel with 5. March Of The Siamese Children 3:14 Al Goodman’s Orchestra Orchestra 17. Shall We Dance 2:43 6. A Puzzlement 3:30 Robert Merrill & Dinah Shore with Yul Brynner Henri René’s Orchestra 7. Getting To Know You 3:26 RCA Victor LK 1022, mx E1-LVC-45/46 Gertrude Lawrence & Chorus Recorded March 1951, New York (tracks 8. We Kiss In A Shadow 3:26 13, 14, 16) & Los Angeles (tracks 15, 17) Larry Douglas & Doretta Morrow Original London Cast, 1954 9. Shall I Tell You What I Think Of You? 18. Getting To Know You 3:27 3:24 Valerie Hobson, King’s Wives & Children 8.120780 8.120787 8.120788 Gertrude Lawrence Philips PB 194, mz AA 26063 2H6 10. -

Leonard A. Anderson M. Seth Re~Nes Execut~Ved~Rector Art~St~Cd~Rector

NATIONAL ALLIANCE Illinois hlrrA-iitlon for MUSICAL THEATRE Leonard A. Anderson M. Seth Re~nes Execut~veD~rector Art~st~cD~rector I I This program is partially supported by a grant from the Illinois Arts Council. Named a Partner In Excellence by the Illinois Arts Council. " ""c. c. I Kari Cataldo, M.D. DECATUR MEMORIAL HOSPITAL I Volney 1. Willett Ill, M.D. Family Practitioner Treating- Babies Children Teens Adults Seniors Call 728-2042 for an appointment. Sullivan Medical Center 1220 West Jackson Sullivan, Illinois MASTERING MODERN -- - Artistic Director Seth Reines, Musical Director Jason Yarcho, Education Director Marie Jagger Taylor and I have recently conducted actor auditions and technical personnel interviews for the 2007 summer season company. We attended the Midwest Theatre Auditions at Wehster University in St. Louis where 55 different theatres auditioned over 400 young actors and actresses and interviewed about 100 theatre technicians. 84 children auditioned here in Sullivan for the children's roles in THE SOUND OF MUSIC and over 65 adults attended our Sullivan auditions. And ... we saw another 87 people at our Actors' Equity Association audition call in Chicago. (In addition, Seth Reines attends other auditions in his role as Artistic Producer for the Prather Family Dinner Theatres and has seen over 700 people.) From all of this, we will assemble a company of approximately 100 people including only 30-35 different actors. I am sure that we have found talented performers who will produce the quality productions that you have become accustomed to here at The Little Theatre On The Square. We are glad you are here and we know you will enjoy the show. -

A Grand Night for Singing

Presented by the Hesston College Music and Theatre Departments Rodgers and Hammerstein’s A Grand Night for Singing Through special arrangement with R&H Theatricals Music by Richard Rodgers Lyrics by Oscar Hammerstein II Conceived by Walter Bobbie Company Elizabeth Arriaga, Seth Baker Gavin Betzelberger, Tony Brown Nicki Coblentz, Erin Hershberger Kendra King, Adam Larson Bethany Miller, Karissa Miller Christine Schweitzer, Katie Wahl, Brad Williams a grand night for singing Sounds of the Earth/Opening Medley Surrey With the Fringe On Top Stepsisters’ Lament We Kiss In A Shadow Hello Young Lovers I’m In Love With A Wonderful Guy I Cain’t Say No Maria Do I Love You Because You’re Beautiful Love Look Away The Gentleman Is A Dope Many A New Day/I’m Gonna Wash That Man Right Outta My Hair If I Loved You Shall We Dance That’s the Way It Happens Act I Finale/Some Enchanted Evening 10-Minute Intermission Oh, What A Beautiful Mornin’ Wedding Sequence The Man I Used To Be It Might As Well Be Spring Parent Medley Honey Bun When You’re Driving Through the Moonlight/A Lovely Night It’s Me Something Wonderful This Nearly Was Mine Impossible/I Have Dreamed Music Director Matt Schloneger Stage Director Megan Tyner Production Staff Stage Manager —Megan Tyner Lightboard Operator—Stephanie Friesen Light Design—Doug Peters Set Construction—Drama Participation Class, Elizabeth Arriaga, Kendra King Bethany Miller, Christine Schweitzer Band Band Leader/Rehearsal Accompanist—Ken Rodgers Keyboard—Linea Bartel Flute/Piccolo/Alto Flute—Vada Snider Flute 2—Naomi Tice Clarinet/Sax—John Banman Bass—Sam Hershberger Percussion—Brad Shores, Jaimie Shores special thanks Jerry Peters, Rob Tierney Music Director’s Note When A Grand Night for Singing opened on Broadway in 1993, it marked the first time that the songs of Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein II had been presented on Broadway in a revue format, more than thirty years after the duo’s final collaboration. -

“Broadway & Musicals” Showcase

“Broadway & Musicals” Showcase “Astaire Dancing: The Musical Films” by John Mueller (1985, HC/DJ). Minimum Bid: $4 With a dancing career that spanned half a century, Fred Astaire displayed unparalleled brilliance, beauty and timeless artistry. To better understand Astaire’s unique choreographic style, this book examines in detail each of the dance scenes of his 31 filmed musicals, Astaire’s personality & working methods, and his numerous contributions to filmed dance. “Glamorous Musicals: Fifty Years of Hollywood’s Ultimate Fantasy” by Ronald Bergen, Foreword by Ginger Rogers (1984, HC/DJ). Minimum Bid: $3 Gorgeous actors, leggy chorus girls, superb dancers & musicians, lavish costumes and sets—all are described with style, wit and perception in this generously illustrated book. Discover the artistry of the stars, and the mastery of the directors & designers, of over 100 Hollywood musicals. CD: “My Fair Lady” With Rex Harrison and Julie Andrews (Digitally Mastered CD of Original 1959 London Recording). Minimum Bid: $2 One of the greatest musical theater shows ever created, My Fair Lady is a charming adaptation of George Bernard Shaw's Pygmalion, pitting flower girl Eliza Doolittle (Julie Andrews) against Prof. Henry Higgins (Rex Harrison), the self-absorbed and ill-tempered linguist who bets that he can turn her into a lady by improving her diction. This classic recording includes popular songs such as: "Wouldn't It Be Loverly," "The Rain in Spain," "I Could Have Danced All Night," "On the Street Where You Live," and "Get Me to the Church on Time." Vintage Souvenir Program and Winter Garden Playbill for “Michael Todd’s Peep Show” (1950, SC). -

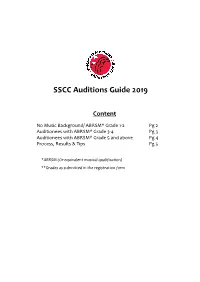

SSCC Auditions Guide 2019

SSCC Auditions Guide 2019 Content No Music Background/ ABRSM* Grade 1-2 Pg 2 Auditionees with ABRSM* Grade 3-4 Pg 3 Auditionees with ABRSM* Grade 5 and above Pg 4 Process, Results & Tips Pg 5 *ABRSM (Or equivalent musical qualification) **Grades as submitted in the registration form (I) NO MUSIC BACKGROUND/ ABRSM GRADE 1-2 Requirements 1. CHOICE PIECE You will need to prepare one song of your choice (preferably classical or from a musical). It may be a favourite song or pick one from the recommended list below. We strongly recommend avoiding pop songs or copying interpretations by pop artists. Do pick a song which you enjoy singing, and also demonstrates your voice quality and musical abilities. Recommended Songs List Category Song Title The Sound of Music The Sound of Music (The hills are alive) My Favourite Things Edelweiss The Lonely Goatherd Do-re-mi The Wizard of Oz Somewhere Over the Rainbow Annie Maybe You’re Never Fully Dressed Without A Smile Les Misérables Castle on a Cloud The King & I Getting to Know You I Whistle a Happy Tune Mary Poppins Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious! Disney When You Wish Upon a Star (Pinocchio) A Dream is a Wish Your Heart Makes (Cinderella) A Whole New World (Aladdin) Oliver Where is Love Consider Yourself Who Will Buy? Others Amazing Grace Simple Gifts Silent Night Do be prepared to sing your choir piece in full. You may sing acapella, or bring a piano accompanist (optional). The use of other instruments or pre-recorded accompaniments is not allowed. (II) AUDITIONEES WITH ABRSM GRADE 3-4 Requirements 1.