Using Computer Content Analysis to Examine Visitor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. 1. Name of Property Historic name: __Kalorama Park____________________________________________ Other names/site number: Little, John, Estate of; Kalorama Park Archaeological Site, 51NW061 Name of related multiple property listing: __N/A_________________________________________________________ (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing ____________________________________________________________________________ 2. Location Street & number: __1875 Columbia Road, NW City or town: ___Washington_________ State: _DC___________ County: ____________ Not For Publication: Vicinity: ____________________________________________________________________________ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering -

Potomac Flats.Pdf

Form 10-306 STATE: (Oct. 1972) NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NFS USE ONLY FOR FEDERAL PROPERTIES ENTRY DATE (Type all entries - complete applicable sections) ———m COMMON: East and West Potomac Parks AND/OR HISTORIC: STREET AND NUMBER: area bounded by Constitution Avenue, 17th Street, Indepen dence Avenue, Washington Channel, Potomac River and Rock Creek Park CITY OR TOWN: CONGRESSIONAL ^ongressman Washington Walter E. Fauntroy, D.C. STATE: CODE COUNTY: District of Columbia 11 District of Columbia 001 CATEGORY ACCESSIBLE OWNERSHIP STATUS (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC [X] District Q Building |XJ Public Public Acquisition: CD Occupied Yes: QSite CD Structure CD Private CD In Process I | Unoccupied I | Restricted CD Object CD Both I | Being Considered [ | Preservation work Qg) Unrestricted in progress LDNo PRESENT USE (Check One of More as Appropriate) I | Agricultural [XJ Government ffi Park 1X1 Transportation | | Commercial CD Industrial CD Private Residence CD Other (Specify) CD Educational CD Military [ | Religious I | Entertainment [~_[ Museum I | Scientific National Park Service, Department of the Interior REGIONAL HEADQUARTERS: (If applicable) STREET AND NUMBER: National Capital Parks 1100 Ohio Drive, S.W. CITY OR TOWN: CODE Washington COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC: None exists—parks are reclaimed land TITLE OF SURVEY: National Park Service survey in compliance with Executive Order 11593 DATE OF SURVEY: [29 Federal CD State CD County CD Local DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS: 09 National Capital Parks STREET AND NUMBER: 1100 Ohio Drive, S.W. Cl TY OR TOWN: Washington District of Columbia 11 ©-©--- - - "- © - - _--_ -.- _---..-- . _ - B& Exc9\\en* [~~| Good- v'Q FVir - "^Q Deteriorated : - fH Ruins "-': - PI Unexposed : CONDWIOK -=."'-". -

Directors of the NPS: a Legacy of Leadership & Foresight Letters •LETTERS What You Missed

RANGThe Journal of the Association of ENational Par Rk Rangers ANPR ~6£SL Stewards for parks, visitors and each other The Association for All National Park Employees Vol. 21, No. 3 • Summer 2005 Directors of the NPS: A Legacy of Leadership & Foresight Letters •LETTERS What you missed ... I unfortunately did not attend the Rapid City Ranger Rendezvous (November 2004) and re Stay in touch! cently read about it in Ranger. There I found the Signed letters to the editor of 100 words or less may be published, space permitting. Please text of the keynote speech by ranger Alden Board of Directors Miller. If for no other reason, reading his include address and daytime phone. Ranger speech made me for the first time truly regret reserves the right to edit letters for grammar or Officers not attending. What a perfect synthesis of length. Send to Editor, 26 S. Mt. Vernon Club President Lee Werst, TICA Secretary Melanie Berg, BADI. history and vision in simple, powerful words! Road, Golden, CO 80401; [email protected]. Treasurer Wendy Lauritzen, WABA It is a great tribute that he has chosen to work with the NPS (and, hopefully, become an Board Members YES! You are welcome to join ANPR ANPR member!). If members haven't read Education 6V; Training Kendell Thompson, ARHO even ifyou don't work for the National Park Fund Raising Sean McGuinness, WASO this, they should, either in the Winter 2004/05 Sen/ice. All friends of the national parks are Interna! Communic. Bill Supernaugh, BADE Ranger (page 8), or at the excellent and infor eligible for membership. -

Rock-Creek-Park-Map.Pdf

To Capital Beltway To Capital Beltway Jo To Capital Beltway To Capital exit 34 exit 33 nes exit 31 Beltway Bridg d e Ro a exit 30 ad o R 390 193 l l i M way h 355 ig s H e n st We o G Ea st J r d u h a b c 410 Ro b n a r B W R e o k ll E i a c v i i s d a e s 410 ol e c s C w o t v P SILVER n i r n i r m e r B r s o F D Meadowbrook s i e D e SPRING n D Rd l Riding Stable a a I t h c S r r c M h o T W D a P R l A e D a I h B C R B t t La r r wbrook r T Y e o o o a P H N O L i d A g hway ROCK CREEK PARK c A t a h F v s h t N e (MD-MCPPC) e e u C D o D n W P S O M Boundary a r u r L Lelan t Candy Bridge k e d ee s U t C r as St Ford Cane id K E o e al M Ro 1 mia n B c City l Rd e k D 7 Ro B n ie ach r t ad I n C i h A e Da D ve r r c G iv ee t r t e e k S W i s e t c n r v r u S a e e e u t l s t e e u t t Juniper Street h e ROCK n e y r e n n v i w Road A e P is k P R W e i Ho u d lly g n e e St 29 v t A u tn S Holly Street A es tre v Ch et T e r ail n e a u k Beech u s e n a rn St Riley Spring l r e e ee Bridge A t v s Aberfolye Place t e A W P 10 t in e eh re urst CREEK St A WALTER REED ARMY e I v B t MEDICAL CENTER A s D 1 9 N M 3 n ran c a o B rrill U e i A h Sh L Tennyson Stree g L t D g O e r Y r en Street r Asp o R C ive A F O 8 e G O M T B Whittier St Battleground CHEVY CHASE C ingham Drive I 12 Rolling Meadow National R Rittenhouse Street 11 T Bridge t Cemetery IS e e D r l t i S Chevy Chase a PARK Park r d 7 Circle T R Police h h t c Stables y 6 n e PUBLIC l 1 a l r a GOLF B V COURSE Rittenhouse St y e d n t Miller Cabin R i 3 -

Draft National Mall Plan / Environmental Impact Statement the National Mall

THE AFFECTED ENVIRONMENT DRAFT NATIONAL MALL PLAN / ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT THE NATIONAL MALL THE MALL CONTENTS: THE AFFECTED ENVIRONMENT THE AFFECTED ENVIRONMENT .................................................................................................... 249 Context for Planning and Development of the National Mall ...................................................................251 1790–1850..................................................................................................................................................251 L’Enfant Plan....................................................................................................................................251 Changes on the National Mall .......................................................................................................252 1850–1900..................................................................................................................................................253 The Downing Plan...........................................................................................................................253 Changes on the National Mall .......................................................................................................253 1900–1950..................................................................................................................................................254 The McMillan Plan..........................................................................................................................254 -

Rock Creek West Area Element ROCK CREEK WEST Colonial Village AREA ELEMENTS

AREA ELEMENTS Chapter 23 Rock Creek West Area Element ROCK CREEK WEST Colonial Village AREA ELEMENTS Hawthorne Rock Barnaby Woods Creek Park ROCK CREEK EAST Chevy Chase MILITARY RD Friendship Heights Friendship Brightwood Park Heights CHAPTER 23: ROCK CREEK WEST CREEK ROCK CHAPTER 23: American University Tenleytown Park Crestwood Forest Hills MASSACHUSETTS AVE North Tenleytown-AU Van Ness Van Ness-UDC Crestwood Spring Valley NEBRASKA AVE McLean Gardens PORTER ST CLARA BARTON PKY Cleveland Park Cathedral Heights Mount Cleveland Park Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park Pleasant Battery Palisades Kemble Wesley Heights Park Woodley Park Lanier Mass. Ave. Heights Heights Woodley Park-Zoo/ Foxhall Adams Morgan Adams Crescents Woodland- Morgan Glover Park Normanstone Terr CANAL RD Kalorama Heights Burleith/ Hillandale NEAR NORTHWEST Dupont Circle Foxhall Georgetown Village West End 16TH ST K ST Connecticut Avenue/K Street Foggy Bottom NEW YORK AVE AREA ELEMENTS AREA ELEMENTS Rock Creek West Area Element CHAPTER 23: ROCK Overview 2300 he Rock Creek West Planning Area encompasses 13 square Tmiles in the northwest quadrant of the District of Columbia. The Planning Area is bounded by Rock Creek on the east, Maryland on the north/west, and the Potomac River and Whitehaven Parkway on the south. Its boundaries are shown in the Map at left. Most of this area has historically been Ward 3 although in past and present times, parts have been included in Wards 1, 2, and 4. 2300.1 Rock Creek West’s most outstanding characteristic is its stable, attractive neighborhoods. These include predominantly single family neighborhoods like Spring Valley, Forest Hills, American University Park, and Palisades; row house and garden apartment neighborhoods like Glover Park and McLean Gardens; and mixed density neighborhoods such as Woodley Park, Chevy Chase, and Cleveland Park. -

Comments Received

PARKS & OPEN SPACE ELEMENT (DRAFT RELEASE) LIST OF COMMENTS RECEIVED Notes on List of Comments: ⁃ This document lists all comments received on the Draft 2018 Parks & Open Space Element update during the public comment period. ⁃ Comments are listed in the following order o Comments from Federal Agencies & Institutions o Comments from Local & Regional Agencies o Comments from Interest Groups o Comments from Interested Individuals Comments from Federal Agencies & Institutions United States Department of the Interior NATIONAL PARK SERVICE National Capital Region 1100 Ohio Drive, S.W. IN REPLY REFER TO: Washington, D.C. 20242 May 14, 2018 Ms. Surina Singh National Capital Planning Commission 401 9th Street, NW, Suite 500N Washington, DC 20004 RE: Comprehensive Plan - Parks and Open Space Element Comments Dear Ms. Singh: Thank you for the opportunity to provide comments on the draft update of the Parks and Open Space Element of the Comprehensive Plan for the National Capital: Federal Elements. The National Park Service (NPS) understands that the Element establishes policies to protect and enhance the many federal parks and open spaces within the National Capital Region and that the National Capital Planning Commission (NCPC) uses these policies to guide agency actions, including review of projects and preparation of long-range plans. Preservation and management of parks and open space are key to the NPS mission. The National Capital Region of the NPS consists of 40 park units and encompasses approximately 63,000 acres within the District of Columbia (DC), Maryland, Virginia and West Virginia. Our region includes a wide variety of park spaces that range from urban sites, such as the National Mall with all its monuments and Rock Creek Park to vast natural sites like Prince William Forest Park as well as a number of cultural sites like Antietam National Battlefield and Manassas National Battlefield Park. -

Rock Creek Park

To Capital Beltway To Capital Beltway Jones To Capital Beltway To Capital Beltway exit 34 exit 33 Bridg d exit 31 exit 30 e R a oad o R 193 390 355 l l i M way igh s H e n st We o Grubb RoadEa st J d h oa c 410 R n ra B W e k ill E v i c s i s 410 a ole e C c w s SILVER o v t n i Primrose e n r e iv s B r D Meadowbrook F D DISTRICTSPRING OF COLUMBIA i e n Riding Stable Road l a a h t e c r iv c r h o MARYLAND W a P D e l D B h a B e t brook Lan r r w e i ort v o o a P Hig e N A h d ROCK CREEK PARK t way c h a t v s (MD-NCPPC) h u e e e D o n W Boundary P S M a r u Lelan t Candy Bridge rk e t d ee s s Connecticut Avenue tr Ford i Ea S Cane de Kalm City B Roc 1 ia Road e k D 7 Roa el ac r t d ani h D C ive h G D ri re ve e S t re k W s S e t r t n r r e e y e v u e a s e a t Juniper Street h t le t ROCK e e w r n n i rk Roa P a ise d P R W id Holly g e Street 29 stnut St Holly Street Che reet Tr ail Beech St Riley Spring re Bridge Alaska Avenue Aberfolye Place et Avenue Western Avenue P 10 i n e CREEK hurst WALTER REED ARMY MEDICAL CENTER 9 31st Street n ran B c errill o h Sh Tennyson Street g D e r r Aspen Street 8 ive Georgia Avenue O MARYLAND Whittier Battleground CHEVY CHASE Bingham Drive Street 12 Rolling Meadow National Rittenhouse Street 11 Bridge Cemetery DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA il Chevy Chase a PARK Park 7 r d Circle T R Police h c Stables y PUBLIC n e a l 16th Street l GOLF r a Rittenhouse B V COURSE y d Street e n R i 30th ha Milkhouse e P w t yc Fort Stevens a S Ford o r n N Miller Cabin J a ewlands ry D To Capital Beltway K lita -

ROCK CREEK PARK: Wild Northern Section

01.60HikesWashingtonDC.pag 1/30/07 1:34 PM Page 52 52 60 hikes within 60 miles: washington, d.c. 09 ROCK CREEK PARK: Wild Northern Section IN BRIEF KEY AT-A-GLANCE i INFORMATION The hilly and little-used woodlands of Rock Creek Park’s northern section rank as one of LENGTH: 9.3 miles (with shorter Washington’s best venues for off-street hiking options) in a wilderness-tinged setting. CONFIGURATION: Modified loop DIFFICULTY: Moderate SCENERY: Gently rolling wood- DESCRIPTION lands, stream valleys The same year that Congress accorded national EXPOSURE: Mostly shady; less so in winter park status to the three big chunks of California TRAFFIC: Usually very light to light; known as Yosemite, Sequoia, and Kings heavier on warm-weather evenings, Canyon, it also preserved a piece of its own weekends, holidays backyard. It decreed that Rock Creek’s valley TRAIL SURFACE: Mostly dirt or stony dirt; some pavement; rocky, rooty in would become “a pleasuring ground for places the benefit and enjoyment of the people of the HIKING TIME: 4.5–5.5 hours United States.” That was in 1890. Today, cover- SEASON: Year-round ing about 2,100 acres, the park consists largely ACCESS: Open daily, dawn–dusk of woodlands and stream valleys that protect the MAPS: USGS Washington West; environment and provide habitat for assorted PATC Map N; ADC Metro Washing- flora and fauna. Most visitors head for the ton; sketch map in free NPS Rock Creek Park brochure picnic areas or other recreation facilities. But FACILITIES: Toilets, water, phone at nature center (open Wednesday– Sunday, 9 a.m.–5 p.m.); toilets near Riley Spring Bridge (warm season Directions only) Head for Northwest Washington. -

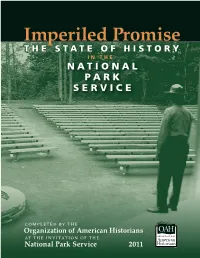

Imperiled Promise the State of History in the N a T I O N a L P a R K Service

Imperiled Promise THE STATE OF HISTORY IN THE N A T I O N A L P A R K SERVICE COMPLETED BY THE Organization of American Historians AT THE INVITATION OF THE National Park Service 2011 Imperiled Promise THE STATE OF HISTORY IN THE N A T I O N A L P A R K SERVICE PREPARED BY THE OAH HISTORY IN THE NPS STUDY TEAM Anne Mitchell Whisnant, Chair Marla R. Miller Gary B. Nash David Thelen COMPLETED BY THE Organization of American Historians AT THE INVITATION OF THE National Park Service 2011 Produced by the Organization of American Historians under a cooperative agreement with the National Park Service. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. Government or the National Park Service. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not consti- tute their endorsement by the U.S. Government. The Organization of American Historians is not an agent or representative of the United States, the Department of the Interior, or the National Park Service. Organization of American Historians 112 North Bryan Avenue, Bloomington, Indiana 47408 http://www.oah.org/ Table of Contents Executive Summary 5 Part 1: The Promise of History in the National Park Servicee 11 About this Study 12 A Stream of Reports 13 Examining the Current State of History within the NPS 15 Making a Case for History, Historians, and Historical Thinking 16 Framing the Challenges: A Brief History of History in the NPS 19 Interpretation vs. -

Junior Ranger Program, National Capital Parks-East

National Park Service Junior Ranger Program U.S. Department of the Interior Washington, D.C. National Capital Parks-East Maryland Table of Contents 2. Letter from the Superintendent 3. National Park Service Introduction 4. National Capital Parks-East Introduction 5. How to Become an Official Junior Ranger 6. Map of National Capital Parks-East 7. Activity 1: National Capital Parks-East: Which is Where? 8. Activity 2: Anacostia Park: Be a Visitor Guide 9. Activity 3: Anacostia Park: Food Chain Mix-Up 10. Activity 4: Mary McLeod Bethune Council House National Historic Site: Create a Timeline 11. Activity 5: Mary McLeod Bethune Council House National Historic Site: Cinquain Poems 12. Activity 6: Fort Dupont Park: Be an Environmentalist 13. Activity 7: Fort Dupont Park: Be a Biologist 14. Activity 8: Fort Washington Park: Be an Architect 15. Activity 9: Fort Washington Park: The Battle of Fort Washington 16. Activity 10: Federick Douglass National Historic Site: Create Your Dream House 17. Activity 11: Frederick Douglass National Historic Site: Scavenger Hunt Bingo 18. Activity 12: Greenbelt Park: Recycle or Throw Away? 19. Activity 13: Greenbelt Park: Be a Detective 20. Activity 14: Kenilworth Park and Aquatic Gardens: What am I? 21. Activity 15: Kenilworth Park and Aquatic Gardens: Be a Consultant 22. Activity 16: Langston Golf Course: Writing History 23. Activity 17: Langston Golf Course: Be a Scientist 24. Activity 18: Oxon Hill Farm: Be a Historian 25. Activity 19: Oxon Hill Farm: Where Does Your Food Come From? 26. Activity 20: Piscataway Park: What’s Wrong With This Picture? 27. Activity 21: Piscataway Park: Be an Explorer 28. -

Rock Creek Park and the Rock Creek and Potomac Parkway

Rock Creek Park National Park Service and the Rock Creek and Potomac Parkway U.S. Department of the Interior Washington, D.C. Rock Creek Park and the Rock Creek and Potomac Parkway Final General Management Plan • Environmental Impact Statement Summary How to Comment on the Plan: Comments on the Final General Management Plan / Environmental Impact Statement, Rock Creek Park and the Rock Creek and Potomac Parkway are welcome and will be accepted for 60 days following publication of notification in the Federal Register. You can submit your comments by mail or elec- tronically. Send written comments to: National Park Service, Rock Creek Park Superintendent 3545 Williamsburg Lane NW Washington, D.C. 20008-1207 You may comment by e-mail by sending comments to: [email protected] Complete, electronic versions of the Final General Management Plan / Environmental Impact Statement, Rock Creek Park and the Rock Creek and Potomac Parkway and its 26-page summary can be reviewed and downloaded as PDF-format files from links at the National Park Service's Rock Creek Park Internet site at: http://www.nps.gov/rocr/pphtml/documents.html There also is a link at this location through which you can provide comments electronically. Regardless of how you comment, please include your name and street address with your message. Please submit electronic comments as a text file, avoid- ing the use of special characters or any form of encryption. It is National Park Service practice to make comments, including names and addresses of respondents, available for public review. Individual respondents may request that we withhold their address from the record, which we will honor to the extent allowable by law.