THE GEORGE WRIGHT Volume 19 2002* Number 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. 1. Name of Property Historic name: __Kalorama Park____________________________________________ Other names/site number: Little, John, Estate of; Kalorama Park Archaeological Site, 51NW061 Name of related multiple property listing: __N/A_________________________________________________________ (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing ____________________________________________________________________________ 2. Location Street & number: __1875 Columbia Road, NW City or town: ___Washington_________ State: _DC___________ County: ____________ Not For Publication: Vicinity: ____________________________________________________________________________ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering -

Directors of the NPS: a Legacy of Leadership & Foresight Letters •LETTERS What You Missed

RANGThe Journal of the Association of ENational Par Rk Rangers ANPR ~6£SL Stewards for parks, visitors and each other The Association for All National Park Employees Vol. 21, No. 3 • Summer 2005 Directors of the NPS: A Legacy of Leadership & Foresight Letters •LETTERS What you missed ... I unfortunately did not attend the Rapid City Ranger Rendezvous (November 2004) and re Stay in touch! cently read about it in Ranger. There I found the Signed letters to the editor of 100 words or less may be published, space permitting. Please text of the keynote speech by ranger Alden Board of Directors Miller. If for no other reason, reading his include address and daytime phone. Ranger speech made me for the first time truly regret reserves the right to edit letters for grammar or Officers not attending. What a perfect synthesis of length. Send to Editor, 26 S. Mt. Vernon Club President Lee Werst, TICA Secretary Melanie Berg, BADI. history and vision in simple, powerful words! Road, Golden, CO 80401; [email protected]. Treasurer Wendy Lauritzen, WABA It is a great tribute that he has chosen to work with the NPS (and, hopefully, become an Board Members YES! You are welcome to join ANPR ANPR member!). If members haven't read Education 6V; Training Kendell Thompson, ARHO even ifyou don't work for the National Park Fund Raising Sean McGuinness, WASO this, they should, either in the Winter 2004/05 Sen/ice. All friends of the national parks are Interna! Communic. Bill Supernaugh, BADE Ranger (page 8), or at the excellent and infor eligible for membership. -

Draft National Mall Plan / Environmental Impact Statement the National Mall

THE AFFECTED ENVIRONMENT DRAFT NATIONAL MALL PLAN / ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT THE NATIONAL MALL THE MALL CONTENTS: THE AFFECTED ENVIRONMENT THE AFFECTED ENVIRONMENT .................................................................................................... 249 Context for Planning and Development of the National Mall ...................................................................251 1790–1850..................................................................................................................................................251 L’Enfant Plan....................................................................................................................................251 Changes on the National Mall .......................................................................................................252 1850–1900..................................................................................................................................................253 The Downing Plan...........................................................................................................................253 Changes on the National Mall .......................................................................................................253 1900–1950..................................................................................................................................................254 The McMillan Plan..........................................................................................................................254 -

Using Computer Content Analysis to Examine Visitor

VISITOR MEANINGS OF PLACE: USING Every year, visitors from the U.S. and other countries flock COMPUTER CONTENT ANALYSIS TO EXAMINE to national parks to understand the places and to be VISITOR MEANINGS AT THREE NATIONAL inspired. Visitors attach significant personal meanings to CAPITOL SITES national park sites such as the Lincoln Memorial and Vietnam Veterans Memorial (Goldman, Chen, & Larsen, in Wei-Li Jasmine Chen press). Quality interpretation requires an effort to integrate knowledge ofthe resource, knowledge ofthe audience, and Doctoral Candidate, Division ofForestry, West Virginia appropriate techniques to yield desired interpretive University, P.O. Box 6125, 322 Percival Hal1, outcomes (NPS, 1997; 2000a; 2000b). Understanding Morgantown, WV 26506 visitors' meanings of place can increase interpreters' knowledge of their audience and regenerate interpreters' Chad L. Pierskal1a passion toward both the resource and the visitors (Goldman et al., in press). Interpretive mangers and front-line Assistant Professor ofRecreation, Parks and Tourism interpreters need a more comprehensive understanding of Resources, Division ofForestry, West Virginia University, the meanings that visitors bring to sites as wel1 as the P.O. Box 6125,.322 Percival Hal1, Morgantown, WV ability to apply that understanding to the development of 26506 interpretive programs. Understanding and interpretation are closely related, and most sociologists now recognize that Theresa L. Goldman some interpretation is involved in the acts ofunderstanding (Marshall, 1994). To help interpreters achieve desired Assistant Professor ofRecreation, Parks and Tourism interpretive outcomes of facilitated intel1ectual and Resources, Division ofForestry, West Virginia University, emotional connections with the resource and therefore a P.O. Box 6125, 322 Percival Hal1,Morgantown, WV sense ofstewardship, this study explored the meanings that 26506 visitors attach to the resources at three National Park Service (NPS) administered sites: National Capital Parks David L. -

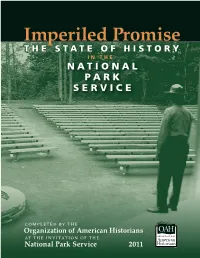

Imperiled Promise the State of History in the N a T I O N a L P a R K Service

Imperiled Promise THE STATE OF HISTORY IN THE N A T I O N A L P A R K SERVICE COMPLETED BY THE Organization of American Historians AT THE INVITATION OF THE National Park Service 2011 Imperiled Promise THE STATE OF HISTORY IN THE N A T I O N A L P A R K SERVICE PREPARED BY THE OAH HISTORY IN THE NPS STUDY TEAM Anne Mitchell Whisnant, Chair Marla R. Miller Gary B. Nash David Thelen COMPLETED BY THE Organization of American Historians AT THE INVITATION OF THE National Park Service 2011 Produced by the Organization of American Historians under a cooperative agreement with the National Park Service. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. Government or the National Park Service. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not consti- tute their endorsement by the U.S. Government. The Organization of American Historians is not an agent or representative of the United States, the Department of the Interior, or the National Park Service. Organization of American Historians 112 North Bryan Avenue, Bloomington, Indiana 47408 http://www.oah.org/ Table of Contents Executive Summary 5 Part 1: The Promise of History in the National Park Servicee 11 About this Study 12 A Stream of Reports 13 Examining the Current State of History within the NPS 15 Making a Case for History, Historians, and Historical Thinking 16 Framing the Challenges: A Brief History of History in the NPS 19 Interpretation vs. -

Junior Ranger Program, National Capital Parks-East

National Park Service Junior Ranger Program U.S. Department of the Interior Washington, D.C. National Capital Parks-East Maryland Table of Contents 2. Letter from the Superintendent 3. National Park Service Introduction 4. National Capital Parks-East Introduction 5. How to Become an Official Junior Ranger 6. Map of National Capital Parks-East 7. Activity 1: National Capital Parks-East: Which is Where? 8. Activity 2: Anacostia Park: Be a Visitor Guide 9. Activity 3: Anacostia Park: Food Chain Mix-Up 10. Activity 4: Mary McLeod Bethune Council House National Historic Site: Create a Timeline 11. Activity 5: Mary McLeod Bethune Council House National Historic Site: Cinquain Poems 12. Activity 6: Fort Dupont Park: Be an Environmentalist 13. Activity 7: Fort Dupont Park: Be a Biologist 14. Activity 8: Fort Washington Park: Be an Architect 15. Activity 9: Fort Washington Park: The Battle of Fort Washington 16. Activity 10: Federick Douglass National Historic Site: Create Your Dream House 17. Activity 11: Frederick Douglass National Historic Site: Scavenger Hunt Bingo 18. Activity 12: Greenbelt Park: Recycle or Throw Away? 19. Activity 13: Greenbelt Park: Be a Detective 20. Activity 14: Kenilworth Park and Aquatic Gardens: What am I? 21. Activity 15: Kenilworth Park and Aquatic Gardens: Be a Consultant 22. Activity 16: Langston Golf Course: Writing History 23. Activity 17: Langston Golf Course: Be a Scientist 24. Activity 18: Oxon Hill Farm: Be a Historian 25. Activity 19: Oxon Hill Farm: Where Does Your Food Come From? 26. Activity 20: Piscataway Park: What’s Wrong With This Picture? 27. Activity 21: Piscataway Park: Be an Explorer 28. -

National Park Service Cultural Landscapes Inventory 2016

National Park Service Cultural Landscapes Inventory 2016 President's Park South The White House (President's Park) Table of Contents Inventory Unit Summary & Site Plan Concurrence Status Geographic Information and Location Map Management Information National Register Information Chronology & Physical History Analysis & Evaluation of Integrity Condition Treatment Bibliography & Supplemental Information President's Park South The White House (President's Park) Inventory Unit Summary & Site Plan Inventory Summary The Cultural Landscapes Inventory Overview: CLI General Information: Purpose and Goals of the CLI The Cultural Landscapes Inventory (CLI) is an evaluated inventory of all significant landscapes in units of the national park system in which the National Park Service has, or plans to acquire any enforceable legal interest. Landscapes documented through the CLI are those that individually meet criteria set forth in the National Register of Historic Places such as historic sites, historic designed landscapes, and historic vernacular landscapes or those that are contributing elements of properties that meet the criteria. In addition, landscapes that are managed as cultural resources because of law, policy, or decisions reached through the park planning process even though they do not meet the National Register criteria, are also included in the CLI. The CLI serves three major purposes. First, it provides the means to describe cultural landscapes on an individual or collective basis at the park, regional, or service-wide level. Secondly, it provides a platform to share information about cultural landscapes across programmatic areas and concerns and to integrate related data about these resources into park management. Thirdly, it provides an analytical tool to judge accomplishment and accountability. -

Anacostia Great Outdoors Factsheet (PDF)

Anacostia’s Great Outdoors: Fact Sheet Connecting People and the Anacostia removal of more than 20 acres of landfill. Additionally, the In partnership with the federal government, the District of project included: planting 85,000 wetland plants, reforesting Columbia and State of Maryland are working to restore the 14 acres of land, creating 20 acres of tidal wetland, and Anacostia River and provide safe and convenient means for preserving four acres of habitat along the Anacostia River. people to access the Anacostia River and enjoy the outdoors. Connecting DC and Maryland The Anacostia Riverwalk Trails will link together hundreds of Maryland, the District, and the U.S. Department of miles of regional trails; including the Fort Circle Trail (DC), the Transportation are working to design and build the critical Bladensburg Trail (MD), the Rock Creek Trail (DC and MD), the Kenilworth Gardens Section, which will connect the Maryland Mount Vernon Trail (VA) and the C&O Canal Trail (DC and and District Anacostia Riverwalk Trail Networks. Design is 65 MD). These connections will also provide access to the East percent complete and construction will begin in 2012. Coast Greenway, a network of trails linking Maine to Florida. Maryland is providing an additional $1 million from the Cycle Maryland Bikeways Program to build this critical connection. Anacostia Riverwalk Trail - DC With 12 miles already in place and a total of 20 miles planned, New Cycle Maryland Bicycle Funding Programs the Anacostia Riverwalk trail in Washington, DC will connect Today, Governor O’Malley announced two new bicycle sixteen waterfront neighborhoods to Anacostia Park and the funding programs to move forward his Cycle Maryland Anacostia River. -

WASHINGTON, D.C. Our Land, Our Water, Our Heritage

WASHINGTON, D.C. Our Land, Our Water, Our Heritage . LWCF Funded Places in Washington, D.C. LWCF Success in Washington, D.C. The Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF) has provided funding to help protect some of Washington, D.C.’s most special places and ensure Federal Program recreational access for hiking, cycling, fishing and other outdoor Ford’s Theatre NHS activities. Washington, D.C. has received approximately $18 million in FDR Memorial LWCF funding over the past five decades, protecting places such as the National Capital Parks-East Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial, Mary McLeod Bethune NHS, and Mary McLeod Bethune NHS National Capital Parks-East. Federal Total $4,200,000 LWCF state assistance grants have further supported hundreds of projects across Washington, D.C.’s local parks including Mitchell Park State Program Playground, Randall Recreation Center, and the East Potomac Park Total State Grants $13,800,000 Swimming Pool. Total $18,000,000 Kenilworth Park and Aquatic Gardens Visitors and residents of Washington, D.C. experience the natural habitat of the area at the beautifully preserved Kenilworth Aquatic Gardens. This wetland helps mitigate pollution, reduces flood damage, and alleviates risks from climate change. As part of the National Capital Parks East, this park which has hiking trails, boardwalks, and comprehensive environmental education resources, has received a portion of the $2.5 million of LWCF awarded to the District’s network of parks. In addition to many events over the year, members of the D.C. Garden Club plant thousands of lotus each spring, a one-of-a-kind spectacle that draws visitors from across town and around the world. -

National Park Service Cultural Landscapes Inventory Marconi

National Park Service Cultural Landscapes Inventory 2007 Marconi Memorial, US Reservation 309 A Rock Creek Park - DC Street Plan Reservations Table of Contents Inventory Unit Summary & Site Plan Concurrence Status Geographic Information and Location Map Management Information National Register Information Chronology & Physical History Analysis & Evaluation of Integrity Condition Treatment Bibliography & Supplemental Information Marconi Memorial, US Reservation 309 A Rock Creek Park - DC Street Plan Reservations Inventory Unit Summary & Site Plan Inventory Summary The Cultural Landscapes Inventory Overview: CLI General Information: Purpose and Goals of the CLI The Cultural Landscapes Inventory (CLI), a comprehensive inventory of all cultural landscapes in the national park system, is one of the most ambitious initiatives of the National Park Service (NPS) Park Cultural Landscapes Program. The CLI is an evaluated inventory of all landscapes having historical significance that are listed on or eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places, or are otherwise managed as cultural resources through a public planning process and in which the NPS has or plans to acquire any legal interest. The CLI identifies and documents each landscape’s location, size, physical development, condition, landscape characteristics, character-defining features, as well as other valuable information useful to park management. Cultural landscapes become approved CLIs when concurrence with the findings is obtained from the park superintendent and all required data fields are entered into a national database. In addition, for landscapes that are not currently listed on the National Register and/or do not have adequate documentation, concurrence is required from the State Historic Preservation Officer or the Keeper of the National Register. -

Fort Chaplin National Capital Parks-East - Fort Circle Park-East

National Park Service Cultural Landscapes Inventory 2017 ..... Fort Chaplin National Capital Parks-East - Fort Circle Park-East Table of Contents Inventory Unit Summary & Site Plan Concurrence Status Geographic Information and Location Map Management Information National Register Information Chronology & Physical History Analysis & Evaluation of Integrity Condition Treatment Bibliography & Supplemental Information Fort Chaplin National Capital Parks-East - Fort Circle Park-East Inventory Unit Summary & Site Plan Inventory Summary The Cultural Landscapes Inventory Overview: CLI General Information: Purpose and Goals of the CLI The Cultural Landscapes Inventory (CLI), a comprehensive inventory of all cultural landscapes in the national park system, is one of the most ambitious initiatives of the National Park Service (NPS) Park Cultural Landscapes Program. The CLI is an evaluated inventory of all landscapes having historical significance that are listed on or eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places, or are otherwise managed as cultural resources through a public planning process and in which the NPS has or plans to acquire any legal interest. The CLI identifies and documents each landscape’s location, size, physical development, condition, landscape characteristics, character-defining features, as well as other valuable information useful to park management. Cultural landscapes become approved CLIs when concurrence with the findings is obtained from the park superintendent and all required data fields are entered -

National Capital Parks – East Climate Action Plan

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior National Capital Parks – East Climate Action Plan www.nps.gov/climatefriendlyparks 1 CONTENTS Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 3 The Challenge of Climate Change ................................................................................................................. 3 National Capital Parks – East Emissions Profile ............................................................................................ 5 Strategies for Reducing Emissions ................................................................................................................ 7 STRATEGY 1: REDUCE GHG EMISSIONS FROM PARK ENERGY USE BY 10 PERCENT BELOW 2008 LEVELS BY 2016 .............................................................................................................................................................. 7 STRATEGY 2: REDUCE GHG EMISSIONS FROM TRANSPORTATION BY 15 PERCENT BELOW 2008 LEVELS BY 2020 .............................................................................................................................................................. 8 STRATEGY 3: REDUCE GHG EMISSIONS FROM WASTE AND WASTEWATER BY 15 PERCENT BELOW 2008 LEVELS BY 2020 ............................................................................................................................................. 9 STRATEGY 4: INCREASE CLIMATE CHANGE AND GREENHOUSE GAS EMISSIONS