BDJ 2014. Peri-Implantitis. Part 1. Scope of the Problem

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Importance of Chlorhexidine in Maintaining Periodontal Health

International Journal of Dentistry Research 2016; 1(1): 31-33 Review Article Importance of Chlorhexidine in Maintaining Periodontal IJDR 2016; 1(1): 31-33 December Health © 2016, All rights reserved www.dentistryscience.com Dr. Manpreet Kaur*1, Dr. Krishan Kumar1 1 Department of Periodontics, Post Graduate Institute of Dental Sciences, Rohtak-124001, Haryana, India Abstract Plaque is responsible for periodontal diseases. In order to prevent occurrence and progression of periodontal disease, removal of plaque becomes important. Mechanical tooth cleaning aids such as toothbrushes, dental floss, interdental brushes are used for removal of plaque. However, in some cases, chemical agents are used as an adjunct to mechanical methods to facilitate plaque control and prevent gingivitis. Chlorhexidine (CHX) mouthwash is the most commonly used and is considered as gold standard chemical agent. In this review, mechanism of action and other properties of CHX are discussed. Keywords: Plaque, Chemical agents, Chlorhexidine (CHX). INTRODUCTION Dental plaque is primary etiologic factor responsible for gingivitis and periodontitis [1]. Mechanical plaque control using toothbrushes, interdental brushes, dental floss prevent occurrence of gingivitis. However, in majority of population, mechanical methods of plaque control are ineffective due to less time spent[2] for plaque removal and lack of consistency. These limitations necessitate use of chemical plaque control agents as an adjunct to mechanical plaque control. Among various chemical agents, chlorhexidine (CHX) is considered to be a gold standard chemical agent for plaque control. Its structural formula consists of two symmetric 4-chlorophenyl rings and two biguanide groups connected by a central hexamethylene chain. Mechanism of action for CHX CHX is bactericidal and is effective against gram-positive bacteria, gram-negative bacteria and yeast organisms. -

Probiotic Alternative to Chlorhexidine in Periodontal Therapy: Evaluation of Clinical and Microbiological Parameters

microorganisms Article Probiotic Alternative to Chlorhexidine in Periodontal Therapy: Evaluation of Clinical and Microbiological Parameters Andrea Butera , Simone Gallo * , Carolina Maiorani, Domenico Molino, Alessandro Chiesa, Camilla Preda, Francesca Esposito and Andrea Scribante * Section of Dentistry–Department of Clinical, Surgical, Diagnostic and Paediatric Sciences, University of Pavia, 27100 Pavia, Italy; [email protected] (A.B.); [email protected] (C.M.); [email protected] (D.M.); [email protected] (A.C.); [email protected] (C.P.); [email protected] (F.E.) * Correspondence: [email protected] (S.G.); [email protected] (A.S.) Abstract: Periodontitis consists of a progressive destruction of tooth-supporting tissues. Considering that probiotics are being proposed as a support to the gold standard treatment Scaling-and-Root- Planing (SRP), this study aims to assess two new formulations (toothpaste and chewing-gum). 60 patients were randomly assigned to three domiciliary hygiene treatments: Group 1 (SRP + chlorhexidine-based toothpaste) (control), Group 2 (SRP + probiotics-based toothpaste) and Group 3 (SRP + probiotics-based toothpaste + probiotics-based chewing-gum). At baseline (T0) and after 3 and 6 months (T1–T2), periodontal clinical parameters were recorded, along with microbiological ones by means of a commercial kit. As to the former, no significant differences were shown at T1 or T2, neither in controls for any index, nor in the experimental -

Sensitive Teeth.Qxp

Sensitive teeth may be a warning of more serious problems Do You Have Sensitive Teeth? If you have a common problem called “sensitive teeth,” a sip of iced tea or a cup of hot cocoa, the sudden intake of cold air or pressure from your toothbrush may be painful. Sensitive teeth can be experienced at any age as a momentary slight twinge to long-term severe discomfort. It is important to consult your dentist because sensitive teeth may be an early warning sign of more serious dental problems. Understanding Tooth Structure. What Causes Sensitive Teeth? To better understand how sensitivity There can be many causes for sensitive develops, we need to consider the teeth. Cavities, fractured teeth, worn tooth composition of tooth structure. The crown- enamel, cracked teeth, exposed tooth root, the part of the tooth that is most visible- gum recession or periodontal disease may has a tough, protective jacket of enamel, be causing the problem. which is an extremely strong substance. Below the gum line, a layer of cementum Periodontal disease is an infection of the protects the tooth root. Underneath the gums and bone that support the teeth. If left enamel and cementum is dentin. untreated, it can progress until bone and other supporting tissues are destroyed. This Dentin is a part of the tooth that contains can leave the root surfaces of teeth exposed tiny tubes. When dentin loses its and may lead to tooth sensitivity. protective covering and is exposed, these small tubes permit heat, cold, Brushing incorrectly or too aggressively may certain types of foods or pressure to injure your gums and can also cause tooth stimulate nerves and cells inside of roots to be exposed. -

Dental Cementum Reviewed: Development, Structure, Composition, Regeneration and Potential Functions

Braz J Oral Sci. January/March 2005 - Vol.4 - Number 12 Dental cementum reviewed: development, structure, composition, regeneration and potential functions Patricia Furtado Gonçalves 1 Enilson Antonio Sallum 1 Abstract Antonio Wilson Sallum 1 This article reviews developmental and structural characteristics of Márcio Zaffalon Casati 1 cementum, a unique avascular mineralized tissue covering the root Sérgio de Toledo 1 surface that forms the interface between root dentin and periodontal Francisco Humberto Nociti Junior 1 ligament. Besides describing the types of cementum and 1 Dept. of Prosthodontics and Periodontics, cementogenesis, attention is given to recent advances in scientific Division of Periodontics, School of Dentistry understanding of the molecular and cellular aspects of the formation at Piracicaba - UNICAMP, Piracicaba, São and regeneration of cementum. The understanding of the mechanisms Paulo, Brazil. involved in the dynamic of this tissue should allow for the development of new treatment strategies concerning the approach of the root surface affected by periodontal disease and periodontal regeneration techniques. Received for publication: October 01, 2004 Key Words: Accepted: December 17, 2004 dental cementum, review Correspondence to: Francisco H. Nociti Jr. Av. Limeira 901 - Caixa Postal: 052 - CEP: 13414-903 - Piracicaba - S.P. - Brazil Tel: ++ 55 19 34125298 Fax: ++ 55 19 3412 5218 E-mail: [email protected] 651 Braz J Oral Sci. 4(12): 651-658 Dental cementum reviewed: development, structure, composition, regeneration and potential functions Introduction junction (Figure 1). The areas and location of acellular Cementum is an avascular mineralized tissue covering the afibrillar cementum vary from tooth to tooth and along the entire root surface. Due to its intermediary position, forming cementoenamel junction of the same tooth6-9. -

Periodontal Practice Patterns

PERIODONTAL PRACTICE PATTERNS A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Janel Kimberlay Yu, D.D.S. Graduate Program in Dentistry The Ohio State University 2010 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Angelo Mariotti, Advisor Dr. Jed Jacobson Dr. Eric Seiber Copyright by Janel Kimberlay Yu 2010 Abstract Background: Differences in the rates of dental services between geographic regions are important since major discrepancies in practice patterns may suggest an absence of evidence-based clinical information leading to numerous treatment plans for similar dental problems and the misallocation of limited resources. Variations in dental care to patients may result from characteristics of the periodontist. Insurance claims data in this study were compared to the characteristics of periodontal providers to determine if variations in practice patterns exist. Methods: Claims data, between 2000-2009 from Delta Dental of Ohio, Michigan, Indiana, New Mexico, and Tennessee, were examined to analyze the practice patterns of 351 periodontists. For each provider, the average number of select CDT periodontal codes (4000-4999), implants (6010), and extractions (7140) were calculated over two time periods in relation to provider variable, including state, urban versus rural area, gender, experience, location of training, and membership in organized dentistry. Descriptive statistics were performed to depict the data using measures of central tendency and measures of dispersion. ii Results: Differences in periodontal procedures were present across states. Although the most common surgical procedure in the study period was osseous surgery, greater increases over time were observed in regenerative procedures (bone grafts, biologics, GTR) when compared to osseous surgery. -

The Cementum: Its Role in Periodontal Health and Disease*

THE JOURNAL OF PERIODONTOLOGY JULY, NINETEEN HUNDRED SIXTY ONE The Cementum: Its Role In Periodontal Health and Disease* by DONALD A. KERR, D.D.S., M.S.,** Ann Arbor, Michigan HE cementum is a specialized calcified tissue of mesenchymal origin which provides for the attachment of the periodontal fibers to the surface of the Troot. It consists of 45 to 50 per cent inorganic material and 50 to 55 per cent organic material with the inorganic material in a hydroxyl apatite structure. The primary cementum is formed initially by appositional growth from the dental sac and later from the periodontal membrane under the influence of cementoblasts. It is formed in laminated layers with the incorporation of Sharpey's fibers into a fibrillar matrix which undergoes calcification. Cementum deposition is a Continuous process throughout life with new cementum being deposited over the old cemental surface. Cementum is formed by the organiza• tion of collagen fibrils which are cemented together by a matrix produced by the polymerization of mucopolysaccharides. This material is designated as cementoid and becomes mature cementum upon calcification. The significance of the continuous deposition of cementum has received various interpretations. 1. Continuous deposition of cementum is necessary for the reattachment of periodontal fibers which have been destroyed or which require reorientation due to change in position of teeth. It is logical that there should be a continuous deposition of cementum because it is doubtful that the initial fibers are retained throughout the life of the tooth, and therefore new fibers must be continually formed and attached by new cementum. -

Classification and Diagnosis of Aggressive Periodontitis

Received: 3 November 2016 Revised: 11 October 2017 Accepted: 21 October 2017 DOI: 10.1002/JPER.16-0712 2017 WORLD WORKSHOP Classification and diagnosis of aggressive periodontitis Daniel H. Fine1 Amey G. Patil1 Bruno G. Loos2 1 Department of Oral Biology, Rutgers School Abstract of Dental Medicine, Rutgers University - Newark, NJ, USA Objective: Since the initial description of aggressive periodontitis (AgP) in the early 2Department of Periodontology, Academic 1900s, classification of this disease has been in flux. The goal of this manuscript is to Center of Dentistry Amsterdam (ACTA), review the existing literature and to revisit definitions and diagnostic criteria for AgP. University of Amsterdam and Vrije Universiteit, Amsterdam, The Netherlands Study analysis: An extensive literature search was performed that included databases Correspondence from PubMed, Medline, Cochrane, Scopus and Web of Science. Of 4930 articles Dr. Daniel H. Fine, Department of Oral reviewed, 4737 were eliminated. Criteria for elimination included; age > 30 years old, Biology, Rutgers School of Dental Medicine, Rutgers University - Newark, NJ. abstracts, review articles, absence of controls, fewer than; a) 200 subjects for genetic Email: fi[email protected] studies, and b) 20 subjects for other studies. Studies satisfying the entrance criteria The proceedings of the workshop were were included in tables developed for AgP (localized and generalized), in areas related jointly and simultaneously published in the Journal of Periodontology and Journal of to epidemiology, microbial, host and genetic analyses. The highest rank was given to Clinical Periodontology. studies that were; a) case controlled or cohort, b) assessed at more than one time-point, c) assessed for more than one factor (microbial or host), and at multiple sites. -

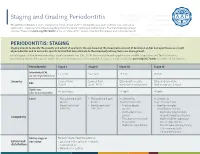

Staging and Grading Periodontitis

Staging and Grading Periodontitis The 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions resulted in a new classification of periodontitis characterized by a multidimensional staging and grading system. The charts below provide an overview. Please visit perio.org/2017wwdc for the complete suite of reviews, case definition papers, and consensus reports. PERIODONTITIS: STAGING Staging intends to classify the severity and extent of a patient’s disease based on the measurable amount of destroyed and/or damaged tissue as a result of periodontitis and to assess the specific factors that may attribute to the complexity of long-term case management. Initial stage should be determined using clinical attachment loss (CAL). If CAL is not available, radiographic bone loss (RBL) should be used. Tooth loss due to periodontitis may modify stage definition. One or more complexity factors may shift the stage to a higher level. Seeperio.org/2017wwdc for additional information. Periodontitis Stage I Stage II Stage III Stage IV Interdental CAL 1 – 2 mm 3 – 4 mm ≥5 mm ≥5 mm (at site of greatest loss) Severity Coronal third Coronal third Extending to middle Extending to middle RBL (<15%) (15% - 33%) third of root and beyond third of root and beyond Tooth loss No tooth loss ≤4 teeth ≥5 teeth (due to periodontitis) Local • Max. probing depth • Max. probing depth In addition to In addition to ≤4 mm ≤5 mm Stage II complexity: Stage III complexity: • Mostly horizontal • Mostly horizontal • Probing depths • Need for -

Sensitive Teeth Sensitive Teeth Can Be Treated

FOR THE DENTAL PATIENT ... TREATMENT Sensitive teeth Sensitive teeth can be treated. Depending on the cause, your dentist may suggest that you try Causes and treatment desensitizing toothpaste, which contains com- pounds that help block sensation traveling from the tooth surface to the nerve. Desensitizing f a taste of ice cream or a sip of coffee is toothpaste usually requires several applications sometimes painful or if brushing or flossing before the sensitivity is reduced. When choosing makes you wince occasionally, you may toothpaste or any other dental care products, look have a common problem called “sensitive for those that display the American Dental Asso- teeth.” Some of the causes include tooth ciation’s Seal of Acceptance—your assurance that Idecay, a cracked tooth, worn tooth enamel, worn products have met ADA criteria for safety and fillings and tooth roots that are exposed as a effectiveness. result of aggressive tooth brushing, gum recession If the desensitizing toothpaste does not ease and periodontal (gum) disease. your discomfort, your dentist may suggest in- office treatments. A fluoride gel or special desen- SYMPTOMS OF SENSITIVE TEETH sitizing agents may be applied to the sensitive A layer of enamel, the strongest substance in the areas of the affected teeth. When these measures body, protects the crowns of healthy teeth. A layer do not correct the problem, your dentist may rec- called cementum protects the tooth root under the ommend other treatments, such as a filling, a gum line. Underneath the enamel and the crown, an inlay or bonding to correct a flaw or cementum is dentin, a part of the tooth that is decay that results in sensitivity. -

The Roots of Periodontology

THE ROOTS OF PERIODONTOLOGY NMDHA 24th Annual Scientific Session Dennis Miller DMD, MS Diplomate, American Board of Periodontology Oct 19, 2012 A word about the value of history…… Those who don’t know history are destined to repeat it. Edmond Burke (1729-1797) Those of you who don’t remember the past are condemned to repeat it. • George Santayama, 1890 The History of Dentistry • Barbers and blacksmiths were the first dentists in America • 1840 – opening of the first dental school, University of Baltimore • 1859 – ADA was founded, oldest and largest national Dental Society in the world • 1890 – Dr. John Riggs describes periodontal disease • Calls it Riggs disease or pyorrhea • Marketed Anti-Riggs mouthwash (156 proof) • 1896 – Dr. G.V. Black who is known as the father of modern dentistry, describes cavity preparations • 1906 – Dr. C. Edmund Kells exposes first dental radiograph; also the first to use female dental assistants and surgical aspirators • 1929 – Orthodontics recognized as first dental specialty History of Periodontics • 1914 – Dr. Grace Rodgers Spalding and Dr. Gillette Hayden (both physicians) formed the American Academy of Oral Prophylaxis and Periodontology • 1919 – became the American Academy of Periodontology • Circa 1941 - Periodontics recognized as a dental specialty History of Hygiene • 1867 – Lucy Hobbs Taylor graduated from Ohio College of Dental Surgery as a hygienist • 1884 – paper presented at the NY 1st District Dental Society meeting advocating teeth cleaning for prevention, done by “staff” • 1923 – formation of ADHA Historical names of periodontitis • Loculosis • Blennorrhea gingivae • Periostitis • Alveolodental periostitis • Infectious arthrodental gingivitis • Phagedenic pericementitis • Expulsive gingivitis • Symptomatic alveolar arthritis • Smutz pyorrhea • Riggs disease • Periodontoclasia • Pyorrhea alveolaris The roots of Periodontology • The roots of the dental profession including periodontics and dental hygiene were not concocted by some entrepreneur. -

Tobacco and Your Oral Health

Oral Wellness Series Tobacco and Your Oral Health We all know smoking is bad for us, but did you know that chewing tobacco is just as harmful to your oral health as cigarettes? Tobacco causes bad breath, which nobody likes, but it has far more serious risks to your oral health, including: • Mouth sores • Slow healing after oral surgery • Difficulties correcting cosmetic dental problems • Stained teeth and tongue • Dulled sense of taste and smell The Biggest Risk? Did you know tobacco Cancer. The Centers for Disease Control have linked smoking and use is a huge risk factor tobacco use to oral cancer. Oral cancer is the eighth most common cancer in the U.S., and it’s very difficult to detect. As a result, two- for gum disease? thirds of all cases are diagnosed in late stages, making treatment and survival difficult.1 Tobacco and Gum Disease Tobacco use is also a huge risk factor for gum disease, a leading cause of tooth loss. More than 41% of daily smokers over the age of 65 are toothless because of gum disease, compared to only 20% of non-smokers.2 Maintain good oral health by avoiding tobacco. It keeps your whole body healthier. The Effects of Smoking on Your Gums Smoking reduces blood flow to your gums, cutting Is Smokeless Tobacco Safer? off vital nutrients and preventing bones from healing. Smokeless tobacco—chew, dip and snuff—is not This lets bacteria from tartar infect surrounding tissue, regulated by the FDA so it’s hard to know what’s in it. 3 forming deep pockets between teeth and gums. -

Sensitive Teeth May Be A

Sensitive Teeth May Be a Warning of More Serious bcbsfepdental.com Problems Sensitive teeth can be experienced at any age, with different levels of pain. When a sip of iced tea, a cup of hot cocoa, or the sudden intake of cold air or pressure from your toothbrush causes pain you may have a common problem called “sensitive teeth.” Sensitive teeth can be experienced at any age as a momentary slight twinge to long-term severe discomfort. It is important to consult with your dentist because sensitive teeth may be an early warning sign of more serious dental problems. Tooth Structure To better understand how sensitivity develops, we need to consider the composition of tooth structure. The crown — the part of the tooth that is most visible — has a tough, protective jacket of enamel, which is an extremely strong substance. Below the gum line, a layer of cementum Do I Need to See My Dentist? protects the tooth root. Underneath the enamel and If you have sensitive teeth, consult your cementum is dentin which contains tiny tubes. When dentin dentist to get a diagnostic evaluation. loses its protective covering (enamel or cementum) from This will determine the extent of the cracks or decay the small dentinal tubules become exposed problem and the treatment. Your permitting heat, cold, certain types of foods or pressure to dentist will evaluate your oral behavior stimulate nerves and cells inside of the tooth. This causes and recommend products that will best teeth to be sensitive producing occasional discomfort. serve you. Causes Dentists can provide mouthguards to minimize the impact of tooth grinding Sensitive teeth can be caused by cavities, fractures (cracked that is the result of clenching or tooth), worn tooth enamel, exposed tooth root, gum bruxing.