Riemannian Geometry – Lecture 15 Riemann Curvature Tensor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Grassmann Manifold

The Grassmann Manifold 1. For vector spaces V and W denote by L(V; W ) the vector space of linear maps from V to W . Thus L(Rk; Rn) may be identified with the space Rk£n of k £ n matrices. An injective linear map u : Rk ! V is called a k-frame in V . The set k n GFk;n = fu 2 L(R ; R ): rank(u) = kg of k-frames in Rn is called the Stiefel manifold. Note that the special case k = n is the general linear group: k k GLk = fa 2 L(R ; R ) : det(a) 6= 0g: The set of all k-dimensional (vector) subspaces ¸ ½ Rn is called the Grassmann n manifold of k-planes in R and denoted by GRk;n or sometimes GRk;n(R) or n GRk(R ). Let k ¼ : GFk;n ! GRk;n; ¼(u) = u(R ) denote the map which assigns to each k-frame u the subspace u(Rk) it spans. ¡1 For ¸ 2 GRk;n the fiber (preimage) ¼ (¸) consists of those k-frames which form a basis for the subspace ¸, i.e. for any u 2 ¼¡1(¸) we have ¡1 ¼ (¸) = fu ± a : a 2 GLkg: Hence we can (and will) view GRk;n as the orbit space of the group action GFk;n £ GLk ! GFk;n :(u; a) 7! u ± a: The exercises below will prove the following n£k Theorem 2. The Stiefel manifold GFk;n is an open subset of the set R of all n £ k matrices. There is a unique differentiable structure on the Grassmann manifold GRk;n such that the map ¼ is a submersion. -

Laplacians in Geometric Analysis

LAPLACIANS IN GEOMETRIC ANALYSIS Syafiq Johar syafi[email protected] Contents 1 Trace Laplacian 1 1.1 Connections on Vector Bundles . .1 1.2 Local and Explicit Expressions . .2 1.3 Second Covariant Derivative . .3 1.4 Curvatures on Vector Bundles . .4 1.5 Trace Laplacian . .5 2 Harmonic Functions 6 2.1 Gradient and Divergence Operators . .7 2.2 Laplace-Beltrami Operator . .7 2.3 Harmonic Functions . .8 2.4 Harmonic Maps . .8 3 Hodge Laplacian 9 3.1 Exterior Derivatives . .9 3.2 Hodge Duals . 10 3.3 Hodge Laplacian . 12 4 Hodge Decomposition 13 4.1 De Rham Cohomology . 13 4.2 Hodge Decomposition Theorem . 14 5 Weitzenb¨ock and B¨ochner Formulas 15 5.1 Weitzenb¨ock Formula . 15 5.1.1 0-forms . 15 5.1.2 k-forms . 15 5.2 B¨ochner Formula . 17 1 Trace Laplacian In this section, we are going to present a notion of Laplacian that is regularly used in differential geometry, namely the trace Laplacian (also called the rough Laplacian or connection Laplacian). We recall the definition of connection on vector bundles which allows us to take the directional derivative of vector bundles. 1.1 Connections on Vector Bundles Definition 1.1 (Connection). Let M be a differentiable manifold and E a vector bundle over M. A connection or covariant derivative at a point p 2 M is a map D : Γ(E) ! Γ(T ∗M ⊗ E) 1 with the properties for any V; W 2 TpM; σ; τ 2 Γ(E) and f 2 C (M), we have that DV σ 2 Ep with the following properties: 1. -

Selected Papers on Teleparallelism Ii

SELECTED PAPERS ON TELEPARALLELISM Edited and translated by D. H. Delphenich Table of contents Page Introduction ……………………………………………………………………… 1 1. The unification of gravitation and electromagnetism 1 2. The geometry of parallelizable manifold 7 3. The field equations 20 4. The topology of parallelizability 24 5. Teleparallelism and the Dirac equation 28 6. Singular teleparallelism 29 References ……………………………………………………………………….. 33 Translations and time line 1928: A. Einstein, “Riemannian geometry, while maintaining the notion of teleparallelism ,” Sitzber. Preuss. Akad. Wiss. 17 (1928), 217- 221………………………………………………………………………………. 35 (Received on June 7) A. Einstein, “A new possibility for a unified field theory of gravitation and electromagnetism” Sitzber. Preuss. Akad. Wiss. 17 (1928), 224-227………… 42 (Received on June 14) R. Weitzenböck, “Differential invariants in EINSTEIN’s theory of teleparallelism,” Sitzber. Preuss. Akad. Wiss. 17 (1928), 466-474……………… 46 (Received on Oct 18) 1929: E. Bortolotti , “ Stars of congruences and absolute parallelism: Geometric basis for a recent theory of Einstein ,” Rend. Reale Acc. dei Lincei 9 (1929), 530- 538...…………………………………………………………………………….. 56 R. Zaycoff, “On the foundations of a new field theory of A. Einstein,” Zeit. Phys. 53 (1929), 719-728…………………………………………………............ 64 (Received on January 13) Hans Reichenbach, “On the classification of the new Einstein Ansatz on gravitation and electricity,” Zeit. Phys. 53 (1929), 683-689…………………….. 76 (Received on January 22) Selected papers on teleparallelism ii A. Einstein, “On unified field theory,” Sitzber. Preuss. Akad. Wiss. 18 (1929), 2-7……………………………………………………………………………….. 82 (Received on Jan 30) R. Zaycoff, “On the foundations of a new field theory of A. Einstein; (Second part),” Zeit. Phys. 54 (1929), 590-593…………………………………………… 89 (Received on March 4) R. -

Riemannian Geometry and the General Theory of Relativity

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1967 Riemannian geometry and the general theory of relativity Marie McBride Vanisko The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Vanisko, Marie McBride, "Riemannian geometry and the general theory of relativity" (1967). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 8075. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/8075 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. p m TH3 OmERAl THEORY OF RELATIVITY By Marie McBride Vanisko B.A., Carroll College, 1965 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts UNIVERSITY OF MOKT/JTA 1967 Approved by: Chairman, Board of Examiners D e a ^ Graduante school V AUG 8 1967, Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. V W Number: EP38876 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduotion is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missir^ pages, these will be noted. Also, if matedal had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT Oi*MMtion neiitNna UMi EP38876 Published ProQuest LLQ (2013). -

Riemannian Geometry Learning for Disease Progression Modelling Maxime Louis, Raphäel Couronné, Igor Koval, Benjamin Charlier, Stanley Durrleman

Riemannian geometry learning for disease progression modelling Maxime Louis, Raphäel Couronné, Igor Koval, Benjamin Charlier, Stanley Durrleman To cite this version: Maxime Louis, Raphäel Couronné, Igor Koval, Benjamin Charlier, Stanley Durrleman. Riemannian geometry learning for disease progression modelling. 2019. hal-02079820v2 HAL Id: hal-02079820 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02079820v2 Preprint submitted on 17 Apr 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Riemannian geometry learning for disease progression modelling Maxime Louis1;2, Rapha¨elCouronn´e1;2, Igor Koval1;2, Benjamin Charlier1;3, and Stanley Durrleman1;2 1 Sorbonne Universit´es,UPMC Univ Paris 06, Inserm, CNRS, Institut du cerveau et de la moelle (ICM) 2 Inria Paris, Aramis project-team, 75013, Paris, France 3 Institut Montpelli`erainAlexander Grothendieck, CNRS, Univ. Montpellier Abstract. The analysis of longitudinal trajectories is a longstanding problem in medical imaging which is often tackled in the context of Riemannian geometry: the set of observations is assumed to lie on an a priori known Riemannian manifold. When dealing with high-dimensional or complex data, it is in general not possible to design a Riemannian geometry of relevance. In this paper, we perform Riemannian manifold learning in association with the statistical task of longitudinal trajectory analysis. -

Curvature Tensors in a 4D Riemann–Cartan Space: Irreducible Decompositions and Superenergy

Curvature tensors in a 4D Riemann–Cartan space: Irreducible decompositions and superenergy Jens Boos and Friedrich W. Hehl [email protected] [email protected]"oeln.de University of Alberta University of Cologne & University of Missouri (uesday, %ugust 29, 17:0. Geometric Foundations of /ravity in (artu Institute of 0hysics, University of (artu) Estonia Geometric Foundations of /ravity Geometric Foundations of /auge Theory Geometric Foundations of /auge Theory ↔ Gravity The ingredients o$ gauge theory: the e2ample o$ electrodynamics ,3,. The ingredients o$ gauge theory: the e2ample o$ electrodynamics 0henomenological Ma24ell: redundancy conserved e2ternal current 5 ,3,. The ingredients o$ gauge theory: the e2ample o$ electrodynamics 0henomenological Ma24ell: Complex spinor 6eld: redundancy invariance conserved e2ternal current 5 conserved #7,8 current ,3,. The ingredients o$ gauge theory: the e2ample o$ electrodynamics 0henomenological Ma24ell: Complex spinor 6eld: redundancy invariance conserved e2ternal current 5 conserved #7,8 current Complete, gauge-theoretical description: 9 local #7,) invariance ,3,. The ingredients o$ gauge theory: the e2ample o$ electrodynamics 0henomenological Ma24ell: iers Complex spinor 6eld: rce carr ry of fo mic theo rrent rosco rnal cu m pic en exte att desc gredundancyiv er; N ript oet ion o conserved e2ternal current 5 invariance her f curr conserved #7,8 current e n t s Complete, gauge-theoretical description: gauge theory = complete description of matter and 9 local #7,) invariance how it interacts via gauge bosons ,3,. Curvature tensors electrodynamics :ang–Mills theory /eneral Relativity 0oincaré gauge theory *3,. Curvature tensors electrodynamics :ang–Mills theory /eneral Relativity 0oincaré gauge theory *3,. Curvature tensors electrodynamics :ang–Mills theory /eneral Relativity 0oincar; gauge theory *3,. -

On Manifolds of Tensors of Fixed Tt-Rank

ON MANIFOLDS OF TENSORS OF FIXED TT-RANK SEBASTIAN HOLTZ, THORSTEN ROHWEDDER, AND REINHOLD SCHNEIDER Abstract. Recently, the format of TT tensors [19, 38, 34, 39] has turned out to be a promising new format for the approximation of solutions of high dimensional problems. In this paper, we prove some new results for the TT representation of a tensor U ∈ Rn1×...×nd and for the manifold of tensors of TT-rank r. As a first result, we prove that the TT (or compression) ranks ri of a tensor U are unique and equal to the respective seperation ranks of U if the components of the TT decomposition are required to fulfil a certain maximal rank condition. We then show that d the set T of TT tensors of fixed rank r forms an embedded manifold in Rn , therefore preserving the essential theoretical properties of the Tucker format, but often showing an improved scaling behaviour. Extending a similar approach for matrices [7], we introduce certain gauge conditions to obtain a unique representation of the tangent space TU T of T and deduce a local parametrization of the TT manifold. The parametrisation of TU T is often crucial for an algorithmic treatment of high-dimensional time-dependent PDEs and minimisation problems [33]. We conclude with remarks on those applications and present some numerical examples. 1. Introduction The treatment of high-dimensional problems, typically of problems involving quantities from Rd for larger dimensions d, is still a challenging task for numerical approxima- tion. This is owed to the principal problem that classical approaches for their treatment normally scale exponentially in the dimension d in both needed storage and computa- tional time and thus quickly become computationally infeasable for sensible discretiza- tions of problems of interest. -

An Introduction to Riemannian Geometry with Applications to Mechanics and Relativity

An Introduction to Riemannian Geometry with Applications to Mechanics and Relativity Leonor Godinho and Jos´eNat´ario Lisbon, 2004 Contents Chapter 1. Differentiable Manifolds 3 1. Topological Manifolds 3 2. Differentiable Manifolds 9 3. Differentiable Maps 13 4. Tangent Space 15 5. Immersions and Embeddings 22 6. Vector Fields 26 7. Lie Groups 33 8. Orientability 45 9. Manifolds with Boundary 48 10. Notes on Chapter 1 51 Chapter 2. Differential Forms 57 1. Tensors 57 2. Tensor Fields 64 3. Differential Forms 66 4. Integration on Manifolds 72 5. Stokes Theorem 75 6. Orientation and Volume Forms 78 7. Notes on Chapter 2 80 Chapter 3. Riemannian Manifolds 87 1. Riemannian Manifolds 87 2. Affine Connections 94 3. Levi-Civita Connection 98 4. Minimizing Properties of Geodesics 104 5. Hopf-Rinow Theorem 111 6. Notes on Chapter 3 114 Chapter 4. Curvature 115 1. Curvature 115 2. Cartan’s Structure Equations 122 3. Gauss-Bonnet Theorem 131 4. Manifolds of Constant Curvature 137 5. Isometric Immersions 144 6. Notes on Chapter 4 150 1 2 CONTENTS Chapter 5. Geometric Mechanics 151 1. Mechanical Systems 151 2. Holonomic Constraints 160 3. Rigid Body 164 4. Non-Holonomic Constraints 177 5. Lagrangian Mechanics 186 6. Hamiltonian Mechanics 194 7. Completely Integrable Systems 203 8. Notes on Chapter 5 209 Chapter 6. Relativity 211 1. Galileo Spacetime 211 2. Special Relativity 213 3. The Cartan Connection 223 4. General Relativity 224 5. The Schwarzschild Solution 229 6. Cosmology 240 7. Causality 245 8. Singularity Theorem 253 9. Notes on Chapter 6 263 Bibliography 265 Index 267 CHAPTER 1 Differentiable Manifolds This chapter introduces the basic notions of differential geometry. -

Riemannian Geometry and Multilinear Tensors with Vector Fields on Manifolds Md

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 5, Issue 9, September-2014 157 ISSN 2229-5518 Riemannian Geometry and Multilinear Tensors with Vector Fields on Manifolds Md. Abdul Halim Sajal Saha Md Shafiqul Islam Abstract-In the paper some aspects of Riemannian manifolds, pseudo-Riemannian manifolds, Lorentz manifolds, Riemannian metrics, affine connections, parallel transport, curvature tensors, torsion tensors, killing vector fields, conformal killing vector fields are focused. The purpose of this paper is to develop the theory of manifolds equipped with Riemannian metric. I have developed some theorems on torsion and Riemannian curvature tensors using affine connection. A Theorem 1.20 named “Fundamental Theorem of Pseudo-Riemannian Geometry” has been established on Riemannian geometry using tensors with metric. The main tools used in the theorem of pseudo Riemannian are tensors fields defined on a Riemannian manifold. Keywords: Riemannian manifolds, pseudo-Riemannian manifolds, Lorentz manifolds, Riemannian metrics, affine connections, parallel transport, curvature tensors, torsion tensors, killing vector fields, conformal killing vector fields. —————————— —————————— I. Introduction (c) { } is a family of open sets which covers , that is, 푖 = . Riemannian manifold is a pair ( , g) consisting of smooth 푈 푀 manifold and Riemannian metric g. A manifold may carry a (d) ⋃ is푈 푖푖 a homeomorphism푀 from onto an open subset of 푀 ′ further structure if it is endowed with a metric tensor, which is a 푖 . 푖 푖 휑 푈 푈 natural generation푀 of the inner product between two vectors in 푛 ℝ to an arbitrary manifold. Riemannian metrics, affine (e) Given and such that , the map = connections,푛 parallel transport, curvature tensors, torsion tensors, ( ( ) killingℝ vector fields and conformal killing vector fields play from푖 푗 ) to 푖 푗 is infinitely푖푗 −1 푈 푈 푈 ∩ 푈 ≠ ∅ 휓 important role to develop the theorem of Riemannian manifolds. -

Differential Geometry: Curvature and Holonomy Austin Christian

University of Texas at Tyler Scholar Works at UT Tyler Math Theses Math Spring 5-5-2015 Differential Geometry: Curvature and Holonomy Austin Christian Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uttyler.edu/math_grad Part of the Mathematics Commons Recommended Citation Christian, Austin, "Differential Geometry: Curvature and Holonomy" (2015). Math Theses. Paper 5. http://hdl.handle.net/10950/266 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Math at Scholar Works at UT Tyler. It has been accepted for inclusion in Math Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholar Works at UT Tyler. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DIFFERENTIAL GEOMETRY: CURVATURE AND HOLONOMY by AUSTIN CHRISTIAN A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Department of Mathematics David Milan, Ph.D., Committee Chair College of Arts and Sciences The University of Texas at Tyler May 2015 c Copyright by Austin Christian 2015 All rights reserved Acknowledgments There are a number of people that have contributed to this project, whether or not they were aware of their contribution. For taking me on as a student and learning differential geometry with me, I am deeply indebted to my advisor, David Milan. Without himself being a geometer, he has helped me to develop an invaluable intuition for the field, and the freedom he has afforded me to study things that I find interesting has given me ample room to grow. For introducing me to differential geometry in the first place, I owe a great deal of thanks to my undergraduate advisor, Robert Huff; our many fruitful conversations, mathematical and otherwise, con- tinue to affect my approach to mathematics. -

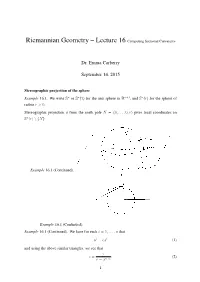

Riemannian Geometry – Lecture 16 Computing Sectional Curvatures

Riemannian Geometry – Lecture 16 Computing Sectional Curvatures Dr. Emma Carberry September 14, 2015 Stereographic projection of the sphere Example 16.1. We write Sn or Sn(1) for the unit sphere in Rn+1, and Sn(r) for the sphere of radius r > 0. Stereographic projection φ from the north pole N = (0;:::; 0; r) gives local coordinates on Sn(r) n fNg Example 16.1 (Continued). Example 16.1 (Continued). Example 16.1 (Continued). We have for each i = 1; : : : ; n that ui = cxi (1) and using the above similar triangles, we see that r c = : (2) r − xn+1 1 Hence stereographic projection φ : Sn n fNg ! Rn is given by rx1 rxn φ(x1; : : : ; xn; xn+1) = ;:::; r − xn+1 r − xn+1 The inverse φ−1 of stereographic projection is given by (exercise) 2r2ui xi = ; i = 1; : : : ; n juj2 + r2 2r3 xn+1 = r − : juj2 + r2 and so we see that stereographic projection is a diffeomorphism. Stereographic projection is conformal Definition 16.2. A local coordinate chart (U; φ) on Riemannian manifold (M; g) is conformal if for any p 2 U and X; Y 2 TpM, 2 gp(X; Y ) = F (p) hdφp(X); dφp(Y )i where F : U ! R is a nowhere vanishing smooth function and on the right-hand side we are using the usual Euclidean inner product. Exercise 16.3. Prove that this is equivalent to: 1. dφp preserving angles, where the angle between X and Y is defined (up to adding multi- ples of 2π) by g(X; Y ) cos θ = pg(X; X)pg(Y; Y ) and also to 2 2. -

SECTIONAL CURVATURE-TYPE CONDITIONS on METRIC SPACES 2 and Poincaré Conditions, and Even the Measure Contraction Property

SECTIONAL CURVATURE-TYPE CONDITIONS ON METRIC SPACES MARTIN KELL Abstract. In the first part Busemann concavity as non-negative curvature is introduced and a bi-Lipschitz splitting theorem is shown. Furthermore, if the Hausdorff measure of a Busemann concave space is non-trivial then the space is doubling and satisfies a Poincaré condition and the measure contraction property. Using a comparison geometry variant for general lower curvature bounds k ∈ R, a Bonnet-Myers theorem can be proven for spaces with lower curvature bound k > 0. In the second part the notion of uniform smoothness known from the theory of Banach spaces is applied to metric spaces. It is shown that Busemann functions are (quasi-)convex. This implies the existence of a weak soul. In the end properties are developed to further dissect the soul. In order to understand the influence of curvature on the geometry of a space it helps to develop a synthetic notion. Via comparison geometry sectional curvature bounds can be obtained by demanding that triangles are thinner or fatter than the corresponding comparison triangles. The two classes are called CAT (κ)- and resp. CBB(κ)-spaces. We refer to the book [BH99] and the forthcoming book [AKP] (see also [BGP92, Ots97]). Note that all those notions imply a Riemannian character of the metric space. In particular, the angle between two geodesics starting at a com- mon point is well-defined. Busemann investigated a weaker notion of non-positive curvature which also applies to normed spaces [Bus55, Section 36]. A similar idea was developed by Pedersen [Ped52] (see also [Bus55, (36.15)]).