The Conservation of Donald Judd's First Concrete

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

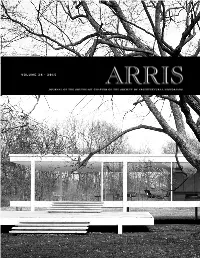

Architectural Photography, the Farnsworth House, and the Opaque Discourse of Transparency SARAH M

VOLUME 26 · 2015 JOURNAL OF THE SOUTHEAST CHAPTER OF THE SOCIETY OF ARCHITECTURAL HISTORIANS Volume 26 · 2015 1 Editors’ Note Articles 6 Madness and Method in the Junkerhaus: The Creation and Reception of a Singular Residence in Modern Germany MIKESCH MUECKE AND NATHANIEL ROBERT WALKER 22 Curtained Walls: Architectural Photography, the Farnsworth House, and the Opaque Discourse of Transparency SARAH M. DRELLER 40 The “Monster Problem”: Texas Architects Try to Keep it Cool Before Air Conditioning BETSY FREDERICK-ROTHWELL 54 Electrifying Entertainment: Social and Urban Modernization through Electricity in Savannah, Georgia JESSICA ARCHER Book Reviews 66 Cathleen Cummings, Decoding a Hindu Temple: Royalty and Religion in the Iconographic Program of the Virupaksha Temple, Pattadakal REVIEWED BY DAVID EFURD 68 Reiko Hillyer, Designing Dixie: Tourism, Memory, and Urban Space in the New South REVIEWED BY BARRY L. STIEFEL 70 Luis E, Carranza and Fernando L. Lara, Modern Architecture in Latin America: Art, Technology, and Utopia REVIEWED BY RAFAEL LONGORIA Field Notes 72 Preserving and Researching Modern Architecture Outside of the Canon: A View from the Field LYDIA MATTICE BRANDT 76 About SESAH ABSTRACTS Sarah M. Dreller Curtained Walls: Architectural Photography, the Farnsworth House, and the Opaque Discourse of Transparency Abstract This paper studies the creation, circulation, and reception of two groups of photographs of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s iconic Farnsworth House, both taken by Hedrich Blessing. The first set, produced for a 1951 Architectural Forum magazine cover story, features curtains carefully arranged according to the architect’s preferences; the Museum of Modern Art commis- sioned the second set in 1985 for a major Mies retrospective exhibition specifically because the show’s influential curator, Arthur Drexler, believed the curtains obscured Mies’ so-called “glass box” design. -

Street & Number 192 Cross Ridge Road___City Or Town New

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) RECEIVED 2280 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service FR 2002 National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete me '" '"'' National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item be marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable". For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items. 1. Name of Property_________________________________________________ historic name LANDIS GORES HOUSE other names/site number N/A 2. Location street & number 192 Cross Ridge Road_________ D not for publication city or town New Canaan________________ _______ D vicinity state Connecticut code CT county Fairfield code 001 zip code .06840. 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this Kl nomination D request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property H meets D does not meet the National Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant DnationaJly-C§ statewide D locally.^£]J5ee continuation sheet for additional comments.) February 4, 2002 Decertifying offfoffirritle ' Date Fohn W. -

Gerard & Kelly

Online Circulation: 9,900 FRIEZE / GERARD & KELLY / JULY 16, 2016 Gerard & Kelly By Evan Moffitt | July 16, 2016 The Glass House, New Canaan, Connecticut, USA The modernist philosophy of Le Corbusier, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and their contemporaries was demo- cratic and utopian – at least until it was realized in concrete, glass and steel. Despite its intention to pro- duce affordable designs for better living, modernism became the principle style for major corporations and government offices, for the architecture of capital and war. Are its original ideals still a worthy goal? I found myself asking that question at the Philip Johnson Glass House in New Canaan, Connecticut, while watch- ing Modern Living (2016), the latest work by performance artist duo Brennan Gerard and Ryan Kelly. As I followed the sloping path to Johnson’s jewel box, pairs of dancers dressed in colourful, loose-fitting garments, mimicking each other’s balletic movements, appeared in emerald folds of lawn. With no accompaniment but the chirping of birds and the crunch of gravel underfoot, I could’ve been watching tai chi at a West Coast meditation re- treat. The influence of postmodern California choreographers, such as the artists’ mentor Simone Forti, was clear. Gerard & Kelly, Modern Living, 2016, documentation of performance, The Glass House, New Canaan; pictured: Nathan Makolandra and Stephanie Amurao. Cour- tesy: Max Lakner/BFA.com When the Glass House was first completed in 1949, Johnson was criticised for producing a voyeuristic do- mestic space in an intensely private era governed by strict sexual mores. Like a fishbowl, the house gave its in- habitants nowhere to hide. -

EAMES HOUSE Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 EAMES HOUSE Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: Eames House Other Name/Site Number: Case Study House #8 2. LOCATION Street & Number: 203 N Chautauqua Boulevard Not for publication: N/A City/Town: Pacific Palisades Vicinity: N/A State: California County: Los Angeles Code: 037 Zip Code: 90272 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: x Building(s): x Public-Local: _ District: Public-State: _ Site: Public-Federal: Structure: Object: Number of Resources within Property Contributing: Noncontributing: 2 buildings sites structures objects Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: None Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: N/A NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 EAMES HOUSE Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this __ nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property __ meets __ does not meet the National Register Criteria. Signature of Certifying Official Date State or Federal Agency and Bureau In my opinion, the property __ meets __ does not meet the National Register criteria. -

Disgrace and Disavowal at the Philip Johnson Glass House

Adele Tutter 449 ADELE TUTTER, M.D., PH.D. The Path of Phocion: Disgrace and Disavowal at the Philip Johnson Glass House Philip Johnson graced his iconic Glass House with a single seicento painting, Landscape with the Burial of Phocion by Nicolas Pous- sin, an intrinsic signifier of the building that frames it. Analyzed within its physical, cultural, and political context, Burial of Phocion condenses displaced, interlacing representations of disavowed aspects of Johnson’s identity, including forbidden strivings for greatness and power, the haunting legacy of the lesser artist, and the humiliation of exile. It is argued that Phocion’s path from disgrace to posthumous dignity is a narrative lens through which Johnson attempted to reframe and disavow his political past. Every time I come away from Poussin I know better who I am. —attributed to PAUL CÉZANNE Is all that we see or seem But a dream within a dream? —EDGAR ALLAN POE, A DREAM WITHIN A DREAM, 18271 An Invitation to Look Although he would during his life amass a formidable collection of contemporary art, the architect Philip Cortelyou Johnson (1906–2005) chose to grace his country residence, the Glass House, with but a single seicento Old Master painting, Nicolas Poussin’s Landscape with the Burial of Phocion,2 which was This study was undertaken with the gracious cooperation of the Philip Johnson Glass House of the National Trust for Historic Preservation. Special thanks go to Dorothy Dunn of The National Trust. The author also wishes to thank Hillary Beat- tie, Steve Brosnahan, David Carrier, Daria Colombo, Wendy Katz, Eric Marcus, Jamie Romm, and Jennifer Stuart, and gratefully acknowledges the generosity of the late Richard Kuhns. -

The Umbrella Diagram Ludwig Mies Van Der Rohe, Farnsworth House

Lecture 3: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Farnsworth House, Plano, Illinois 1946-51 The Umbrella Diagram Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Farnsworth House S. Hambright Drawing Canonical Ideas in Architecture UofA Lecture 3: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Farnsworth House, Plano, Illinois 1946-51 “Less is more” or “Less is a bore” “Roland Barthes’s citation of ‘the boring’ as a locus of resistance…” “the Farnsworth House reveals important deviations from the modernist conventions of the open plan and the expression of structure.” Andy Warhol Campbell’s Soup Cans 1962 According to Barthes, how is ‘boring’ good? What does he mean by ‘locus of resistance.’ S. Hambright Drawing Canonical Ideas in Architecture UofA Lecture 3: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Farnsworth House, Plano, Illinois 1946-51 Le Corbusier : Maison Dom-ino and the Maison Citrohan “…the Farnsworth House marks one of the beginnings of the breakdown of the classical part-to-whole unity of the house.” S. Hambright Drawing Canonical Ideas in Architecture UofA Lecture 3: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Farnsworth House, Plano, Illinois 1946-51 Gerrit Rietveld: Schroeder House, Utrecht, Netherlands “…these were still single, definable entities.” S. Hambright Drawing Canonical Ideas in Architecture UofA Lecture 3: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Farnsworth House, Plano, Illinois 1946-51 Mies van der Rohe, Concrete Country House, 1923, Germany “…these were still single, definable entities.” S. Hambright Drawing Canonical Ideas in Architecture UofA Lecture 3: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Farnsworth House, Plano, Illinois 1946-51 Mies van der Rohe, Brick country House, 1924, Neubabelsberg, Germany “…these were still single, definable entities.” S. -

Two Hour Private Tour of Philip Johnson's Glass House

A.R.C FINE ART LLC TWO HOUR PRIVATE TOUR OF !!PHILIP JOHNSON'S GLASS HOUSE ! New Canaan, Connecticut!! The Tour will be led by !Christa Carr, former Christie's 20th Century Specialist and! Art Advisor for Lord Rothschild!! Tour includes access to the interiors of the Glass House, !Painting Gallery, Sculpture Gallery and da Monsta. !This tour allows photography Monday, May 3, 2010 2:00 ~ 4:00 pm!!Monday, May 10, 2010 1 :00 ~ 3:00 pm !!Monday, May 24, 2010 1:00 ~ 3:00pm!!Wednesday, June 2, 2010 2:30 ~ 4:30 pm !! $50/person!!Each tour limited to 12 people!! Lunch prior to tour at Le Pain Quotidien! 81 Elm Street, New Canaan !!rsvp with preferred date to [email protected] Philip Cortelyou Johnson was born in Cleveland, Ohio in 1906. Following his graduation from Harvard's Graduate School of Design in 1943, Johnson designed some of America's greatest modern architectural landmarks. Most notable is his private residence, the Glass House, a 47-acre property in New Canaan, Connecticut. Other works include: the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Sculpture Garden at The Museum of Modern Art, numerous homes, New York's AT&T Building (now Sony Plaza), Houston's Transco (now Williams) Tower and Pennzoil Place, the Fort Worth Water Garden, and the Crystal Cathedral in Garden Grove, California. An associate of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe in the 1950s, Johnson worked with the modern master on the design of the Seagram Building and its famed Four Seasons Restaurant. Before practicing architecture, Johnson was the founding Director of the Department of Architecture at The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York. -

The Entire Modern Movement – Looked At

2018.11.16 Philip Johnson (July 8, 1906 – Jan. 25, 2005) 10:00 “The entire modern movement – looked at as an intellectual movement dating from Ruskin and Viollet-le-Duc, going through the Werkbund, Bauhaus, Le Corbusier to World War II – may be winding up its days. There is only one absolute today and that is change. There are no rules, surely no certainties in any of the arts. There is only the feeling of a wonderful freedom, of endless past years of historically great buildings to enjoy. I cannot worry about a new eclecticism. Even Richardson who considered himself an eclectic was not one. A good architect will always do original work. A bad one would do bad ‘modern’ work as well as bad work, that is imitative with historical forms. Structural honesty seems to me one of the bugaboos that we should free ourselves from very quickly. The Greeks with their marble columns imitating wood, and covering up the wood roofs inside! The Gothic designers with their wooden roofs above to protect their delicate vaulting. And Michelangelo, the greatest architect in history, with his Mannerist column! No, our day no longer has need of moral crutches of late 19th century vintage. If Villet-le-Duc was what the young Frank Lloyd Wright was nurtured on, Geoffrey Scott and Russell Hitchcock were my Bibles. I am old enough to have enjoyed the International Style immensely and worked in it with the greatest pleasure. I still believe Le Corbusier and Mies to be the greatest living architects. But now the age is changing so fast. -

Philip Johnson Glass House, the : an Architect in the Garden Pdf, Epub, Ebook

PHILIP JOHNSON GLASS HOUSE, THE : AN ARCHITECT IN THE GARDEN PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Maureen Cassidy-Geiger | 224 pages | 21 Jul 2016 | Rizzoli International Publications | 9780847848362 | English | New York, United States Philip Johnson Glass House, The : An Architect in the Garden PDF Book Creating visual interest in a winter garden can be. Sign up today. Philip Johnson. Your Email Address. Titles By Category. Aerial view of the estate in , with paths leading from the parking area on the left to the Glass House and Brick House; the pavillion on the pond and the Monument to Lincoln Kirstein tower in the woodland can also be seen. Share Share Facebook. Above: Johnson and his partner, David Whitney, were passionate about the trees and wanted light to penetrate to the bottom of the forest floor. Join the conversation. The interior of the Glass House is completely exposed to the outdoors except for the a cylinder brick structure with the entrance to the bathroom on one side and a fireplace on the other side. Sign in or become a member now. Learn More. You must be a Member to post a comment. Above: When Johnson acquired the land, he found a number of old stone walls from early farming days, which he loved, preserved, and added to. The acre campus is an example of the successful preservation and interpretation of modern architecture, landscape, and art. Want to Read saving…. Sort order. The house was the first of fourteen structures that the architect built on the property over a span of fifty years. What gardening and landscape projects do you have. -

Philip Johnson Glass House & Garden Tour Thursday, August 13, 2020

Philip Johnson Glass House & Garden Tour Thursday, August 13, 2020 6:45 am – Arrive at the Museums’ State Street parking lot located directly across the street from the Springfield City Library. Park in the lot and board the bus at the curbside. Depart at 7 am sharp. 9:45 am – Estimated arrival at the Philip Johnson Glass House. Philip Johnson designed some of America’s greatest modern architectural landmarks--Most notable his private residence the Glass House – a 47-acre property in New Canaan, Connecticut. We’ll have a private guided tour of the glass house and galleries complete with a world-class art collection, original furnishings, décor and stunning views of the country landscape from the interior. This private tour of the Glass House and garden will last 2 hours and includes approximately ¾ mile walk across uneven and hilly terrain. The site is ADA accessible and on-site transport is available with advance notice. An associate of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe in the 1950s, Johnson worked with the modern master on the design of the Seagram Building and its famed Four Seasons Restaurant. Other works include: the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Sculpture Garden at The Museum of Modern Art, numerous homes, New York’s AT&T Building (now Sony Plaza), Houston’s Transco (now Williams) Tower and Pennzoil Place, the Fort Worth Water Garden, and the Crystal Cathedral in Garden Grove, California. Before practicing architecture, Johnson was the founding Director of the Department of Architecture at The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York. His landmark 1932 exhibition, The International Style, introduced modern architecture to the American public. -

Farnsworth House™ Plano, Illinois, USA

Farnsworth House™ Plano, Illinois, USA Booklet available on: Livret disponible sur: Folleto disponible en: Architecture.LEGO.com 21009_.indd 1 02/03/2011 12:23 PM Ludwig Mies van der Rohe Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, born Maria Ludwig Michael Mies (March 27, 1886 – August 17, 1969) was an architect and designer. Mies has long been considered one of the most important architects of the 20th century. In Europe, before World War II, Mies emerged as one of the most innovative leaders of the Modern Movement, producing visionary projects and executing a number of small but critically significant buildings. After emigrating to the United States in 1938, he transformed the architectonic expression of the steel frame in American architecture and left a nearly unmatched legacy of teaching and building. Born in Aachen, Germany, Mies began his architectural career as an apprentice at the studio of Peter Behrens from 1908 to 1912. There he was exposed to progressive German culture, working alongside Walter Gropius and Le Corbusier. Determined to establish a new architectural style that could represent modern times just as Classical and Gothic had done for their own eras, Mies began to develop projects that, though most remained unbuilt, rocketed him to fame as a progressive architect. His dramatic modernist debut was his stunning competition proposal for the all-glass Friedricstrasse skyscraper in 1921. He continued with a whole series of pioneering projects, including the temporary German Pavilion for the Barcelona exposition (often called the Barcelona Pavilion) in 1929. In the 1930s he joined the avant-garde Bauhaus design school as director, but faced with growing Nazi political pressure decided to emigrate to America in 1938. -

Ultra: I Was There Volume I

Ultra: I Was There Volume I To My Loves Ultra: I Was There Volume I Landis Gores Ultra: I Was There. Copyright © 2008 by Karl Gores Whitmarsh All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the author or publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast. Published in the United States by Lulu Publishing, Inc. Visit us at www.Lulu.com Table of Contents for Volume I About the Author.......................................................................................................................................... iii Author's Preface............................................................................................................................................. v Notes on Modes, Methods and Militarese .............................................................................................. xiii Maps drawn by the author........................................................................................................................... x I Entry Station: Euston.......................................................................................................................... 3 At Bletchley Park................................................................................................................................