NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bauhaus 1 Bauhaus

Bauhaus 1 Bauhaus Staatliches Bauhaus, commonly known simply as Bauhaus, was a school in Germany that combined crafts and the fine arts, and was famous for the approach to design that it publicized and taught. It operated from 1919 to 1933. At that time the German term Bauhaus, literally "house of construction" stood for "School of Building". The Bauhaus school was founded by Walter Gropius in Weimar. In spite of its name, and the fact that its founder was an architect, the Bauhaus did not have an architecture department during the first years of its existence. Nonetheless it was founded with the idea of creating a The Bauhaus Dessau 'total' work of art in which all arts, including architecture would eventually be brought together. The Bauhaus style became one of the most influential currents in Modernist architecture and modern design.[1] The Bauhaus had a profound influence upon subsequent developments in art, architecture, graphic design, interior design, industrial design, and typography. The school existed in three German cities (Weimar from 1919 to 1925, Dessau from 1925 to 1932 and Berlin from 1932 to 1933), under three different architect-directors: Walter Gropius from 1919 to 1928, 1921/2, Walter Gropius's Expressionist Hannes Meyer from 1928 to 1930 and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe Monument to the March Dead from 1930 until 1933, when the school was closed by its own leadership under pressure from the Nazi regime. The changes of venue and leadership resulted in a constant shifting of focus, technique, instructors, and politics. For instance: the pottery shop was discontinued when the school moved from Weimar to Dessau, even though it had been an important revenue source; when Mies van der Rohe took over the school in 1930, he transformed it into a private school, and would not allow any supporters of Hannes Meyer to attend it. -

Seagram Building, First Floor Interior

I.andmarks Preservation Commission october 3, 1989; Designation List 221 IP-1665 SEAGRAM BUIIDING, FIRST FLOOR INTERIOR consisting of the lobby and passenger elevator cabs and the fixtures and interior components of these spaces including but not limited to, interior piers, wall surfaces, ceiling surfaces, floor surfaces, doors, railings, elevator doors, elevator indicators, and signs; 375 Park Avenue, Manhattan. Designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe with Philip Johnson; Kahn & Jacobs, associate architects. Built 1956-58. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 1307, Lot 1. On May 17, 1988, the landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Seagram Building, first floor interior, consisting of the lobby and passenger elevator cabs and the fixtures and interior components of these spaces including but not limited to, interior piers, wall surfaces, ceiling surfaces, floor surfaces, doors, railings, elevator doors, elevator indicators, and signs; and the proposed designation of the related I.and.mark Site (Item No. 2). The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. Twenty witnesses, including a representative of the building's owner, spoke in favor of designation. No witnesses spoke in opposition to designation. The Commission has received many letters in favor of designation. DFSCRIPI'ION AND ANALYSIS Summary The Seagram Building, erected in 1956-58, is the only building in New York City designed by architectural master Iudwig Mies van der Rohe. Constructed on Park Avenue at a time when it was changing from an exclusive residential thoroughfare to a prestigious business address, the Seagram Building embodies the quest of a successful corporation to establish further its public image through architectural patronage. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form NPS Form 10-900 OMB No

United States Department of the Interior National Park Service / National Register of Historic Places Registration Form NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (Expires 5/31/2012) Washington State Library Thurston County, WA Name of Property County and State United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter “N/A” for “not applicable.” For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional certification comments, entries, and narrative items on continuation sheets if needed (NPS Form 10-900a). 1. Name of Property historic name Washington State Library other names/site number Joel M. Pritchard Building 2. Location th street and 415 15 Avenue Southeast not for publication number city or town Olympia vicinity state Washington code WA county Thurston code 067 zip code 98501 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this nomination request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property _ meets _ does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant at the following level(s) of significance: local Applicable National Register Criteria A C Signature of certifying official/Title Date WASHINGTON SHPO State or Federal agency/bureau or Tribal Government In my opinion, the property meets does not meet the National Register criteria. -

EU Prize for Contemporary Architecture / Mies Van Der Rohe Award: a Tribute to Bauhaus

AT A GLANCE EU Prize for Contemporary Architecture / Mies van der Rohe Award: A tribute to Bauhaus The EU Prize for Contemporary Architecture (also known as the EU Mies Award) was launched in recognition of the importance and quality of European architecture. Named after German architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, a figure emblematic of the Bauhaus movement, it aims to promote functionality, simplicity, sustainability and social vision in urban construction. Background Mies van der Rohe was the last director of the Bauhaus school. The official lifespan of the Bauhaus movement in Germany was only fourteen years. It was founded in 1919 as an educational project devoted to all art forms. By 1933, when the Nazi authorities closed the school, it had changed location and director three times. Artists who left continued the work begun in Germany wherever they settled. Recognition by Unesco The Bauhaus movement has influenced architecture all over the world. Unesco has recognised the value of its ideas of sober design, functionalism and social reform as embodied in the original buildings, putting some of the movement's achievements on the World Heritage List. The original buildings located in Weimar (the Former Art School, the Applied Art School and the Haus Am Horn) and Dessau (the Bauhaus Building and the group of seven Masters' Houses) have featured on the list since 1996. Other buildings were added in 2017. The list also comprises the White City of Tel-Aviv. German-Jewish architects fleeing Nazism designed many of its buildings, applying the principles of modernist urban design initiated by Bauhaus. -

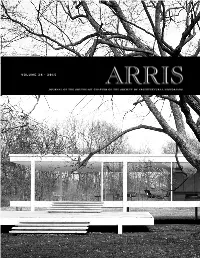

Architectural Photography, the Farnsworth House, and the Opaque Discourse of Transparency SARAH M

VOLUME 26 · 2015 JOURNAL OF THE SOUTHEAST CHAPTER OF THE SOCIETY OF ARCHITECTURAL HISTORIANS Volume 26 · 2015 1 Editors’ Note Articles 6 Madness and Method in the Junkerhaus: The Creation and Reception of a Singular Residence in Modern Germany MIKESCH MUECKE AND NATHANIEL ROBERT WALKER 22 Curtained Walls: Architectural Photography, the Farnsworth House, and the Opaque Discourse of Transparency SARAH M. DRELLER 40 The “Monster Problem”: Texas Architects Try to Keep it Cool Before Air Conditioning BETSY FREDERICK-ROTHWELL 54 Electrifying Entertainment: Social and Urban Modernization through Electricity in Savannah, Georgia JESSICA ARCHER Book Reviews 66 Cathleen Cummings, Decoding a Hindu Temple: Royalty and Religion in the Iconographic Program of the Virupaksha Temple, Pattadakal REVIEWED BY DAVID EFURD 68 Reiko Hillyer, Designing Dixie: Tourism, Memory, and Urban Space in the New South REVIEWED BY BARRY L. STIEFEL 70 Luis E, Carranza and Fernando L. Lara, Modern Architecture in Latin America: Art, Technology, and Utopia REVIEWED BY RAFAEL LONGORIA Field Notes 72 Preserving and Researching Modern Architecture Outside of the Canon: A View from the Field LYDIA MATTICE BRANDT 76 About SESAH ABSTRACTS Sarah M. Dreller Curtained Walls: Architectural Photography, the Farnsworth House, and the Opaque Discourse of Transparency Abstract This paper studies the creation, circulation, and reception of two groups of photographs of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s iconic Farnsworth House, both taken by Hedrich Blessing. The first set, produced for a 1951 Architectural Forum magazine cover story, features curtains carefully arranged according to the architect’s preferences; the Museum of Modern Art commis- sioned the second set in 1985 for a major Mies retrospective exhibition specifically because the show’s influential curator, Arthur Drexler, believed the curtains obscured Mies’ so-called “glass box” design. -

Street & Number 192 Cross Ridge Road___City Or Town New

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) RECEIVED 2280 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service FR 2002 National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete me '" '"'' National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item be marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable". For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items. 1. Name of Property_________________________________________________ historic name LANDIS GORES HOUSE other names/site number N/A 2. Location street & number 192 Cross Ridge Road_________ D not for publication city or town New Canaan________________ _______ D vicinity state Connecticut code CT county Fairfield code 001 zip code .06840. 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this Kl nomination D request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property H meets D does not meet the National Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant DnationaJly-C§ statewide D locally.^£]J5ee continuation sheet for additional comments.) February 4, 2002 Decertifying offfoffirritle ' Date Fohn W. -

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project ELEANOR LOPES “PENNY” AKAHLOUN Interviewed by: Daniel F. Whitman Initial interview date: July 19, 2008 Copyright 2015 ADST TABLE OF CONTENTS MY FORMATIVE YEARS, 1943–1965 Born and raised in Onset, Massachusetts Cape Verdean History and Whaling Ships The Schooner Ernestina and the Packet Trade Small, Round, and Copper Tone Harsh Life for Cape Verdeans on the Cranberry Bogs Vera Cruz VII Shipwreck at Ocracoke, North Carolina Rescue of the Passengers Grandfather’s Marriage and the Curse Oak Grove School Prejudice and “Jungletown” My Big Dream at Age 8 Moving from Cape Cod to Boston, Massachusetts No Vacancy at Bethany Union If First You Don’t Succeed, Try and Try Again Massachusetts Attorney General Edward W. Brooke and a Second Chance Joining the Foreign Service THE PHILIPPINES, 1965–1967 1 The Right Place at the Right Time Shooting the Rapids at Pagsanjan Falls, Laguna Electric Typewriters, Carbons and Pencil Erasers Vice President Hubert Humphrey Attends President Ferdinand Marcos’ 1965 Inauguration Bike Rides on the Island of Mindanao Holy Week in Bongabong, Oriental Mindoro The Eclipse of Sukarno and the Rise of Suharto Bombs Rain Down on Saigon Skies President Lyndon Johnson and the Seven-Nation Manila Summit U.S. -Philippine Relations Around the World and Home in One Piece WASHINGTON, DC, AND HOME LEAVE, LATE 1967 Reverse Cultural Shock Vietnam War Demonstrations MOROCCO, 1968–1970 The Moroccan Treaty of Friendship, the Longest Unbroken Accord in U.S. History Disappearance of Mehdi Ben Barka U.S.-Moroccan Relations Marrakech’s Djema El Fna Square and Snake Charmers A Sense of Being Home A Muslim and a Christian Fall in Love The State Department’s Historical 1972 Directive Permission Granted to Marry a U.S. -

Modernism's Influence on Architect-Client Relationship

World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology International Journal of Architectural and Environmental Engineering Vol:12, No:10, 2018 Modernism’s Influence on Architect-Client Relationship: Comparative Case Studies of Schroder and Farnsworth Houses Omneya Messallam, Sara S. Fouad beliefs in accordance with modern ideas, in the late 19th and Abstract—The Modernist Movement initially flourished in early 20th centuries. Additionally, [2] explained it as France, Holland, Germany and the Soviet Union. Many architects and specialized ideas and methods of modern art, especially in the designers were inspired and followed its principles. Two of its most simple design of buildings of the 1940s, 50s and 60s which important architects (Gerrit Rietveld and Ludwig Mies van de Rohe) were made of modern materials. On the other hand, [3] stated were introduced in this paper. Each did not follow the other’s principles and had their own particular rules; however, they shared that, it has meant so much that it has often meant nothing. the same features of the Modernist International Style, such as Anti- Perhaps, the belief of [3] stemmed from a misunderstanding of historicism, Abstraction, Technology, Function and Internationalism/ the definitions of Modernism, or what might be true is that it Universality. Key Modernist principles translated into high does not have a clear meaning to be understood. Although this expectations, which sometimes did not meet the inhabitants’ movement was first established in Europe and America, it has aspirations of living comfortably; consequently, leading to a conflict become global. Applying Modernist principles on residential and misunderstanding between the designer and their clients’ needs. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

B-4480 NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking V in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word process, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name One Charles Center other names B-4480 2. Location street & number 100 North Charles Street Q not for publication city or town Baltimore • vicinity state Maryland code MP County Independent city code 510 zip code 21201 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this G3 nomination • request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property C3 meets • does not meet the National Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant D nationally • statewide K locally. -

Flooded at the Farnsworth House MICHAEL CADWELL the Ohio State University

392 THE ART OF ARCHITECTURE/THE SCIENCE OF ARCHITECTURE Flooded at the Farnsworth House MICHAEL CADWELL The Ohio State University In 1988, nearly twenty years after his mentor’s the means by which this drama unfolded. Duckett’s death, the architect Edward A. Duckett remem- stick and his act of framing recall the central ar- bered an afternoon outing with Mies van der Rohe. chitectural activity of drawing: the stick, now a One time we were out at the Farnsworth House, pencil, describes a frame, now a building, which and Mies and several of us decided to walk down affords a particular view of the world. In this es- to the river’s edge. So we were cutting a path say, I will elaborate on the peculiar intertwining of through the weeds. I was leading and Mies was building, drawing, and nature at the Farnsworth right behind me. Right in front of me I saw a young House; how drawing erases a positivist approach possum. If you take a stick and put it under a young to building technology and how, in turn, a pro- possum’s tail, it will curl its tail around the stick found respect for the natural world deflects and, and you can hold it upside down. So I reached finally, absorbs the unifying thrust of perspective. down, picked up a branch, stuck it under this little possum’s tail and it caught onto it and I turned Approached by Dr. Farnsworth in the winter of around and showed it to Mies. Now, this animal is 1946/7 to design a weekend house, Mies responded thought by many to be one of the world’s ugliest, with uncharacteristic alacrity. -

Forumjournal VOL

ForumJournal VOL. 32, NO. 3 Heritage in the Landscape Contents NATIONAL TRUST FOR HISTORIC PRESERVATION VOL. 32, NO. 3 PAUL EDMONDSON President & CEO Cultural Landscapes and the National Register KATHERINE MALONE-FRANCE BARBARA WYATT ...............................................3 Chief Preservation Officer TABITHA ALMQUIST Chief Administrative Officer Large-Landscape Conservation: A New Frontier THOMPSON M. MAYES for Cultural Heritage Chief Legal Officer & BRENDA BARRETT ............................................. 13 General Counsel PATRICIA WOODWORTH Honoring and Preserving Hawaiian Cultural Interim Chief Financial Officer Landscapes GEOFF HANDY Chief Marketing Officer BY DAVIANNA PŌMAIKA‘I MCGREGOR .............................22 PRESERVATION Stewarding and Activating the Landscape LEADERSHIP FORUM of the Farnsworth House SUSAN WEST MONTGOMERY SCOTT MEHAFFEY. .30 Vice President, Preservation Resources Tribal Heritage at the Grand Canyon: RHONDA SINCAVAGE Director, Publications and Protecting a Large Ethnographic Landscape Programs to Sustain Living Traditions SANDI BURTSEVA BRIAN R. TURNER .............................................. 41 Content Manager KERRI RUBMAN Assistant Editor Meshing Conservation and Preservation Goals PRIYA CHHAYA with the National Register Associate Director, ELIZABETH DURFEE HENGEN AND JENNIFER GOODMAN .............50 Publications and Programs MARY BUTLER Adapting to Maintain a Timeless Garden at Filoli Creative Director KARA NEWPORT . 61 Cover: Beach Ridges on the Shore of Cape Krusenstern, part of Cape Krusenstern National Monument in Alaska PHOTO COURTESY OF NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Forum Journal, a publication of the National Trust for Historic Preservation (ISSN 1536-1012), is published by the Preservation Resources Department at the National Trust for Historic Preservation, 2600 Virginia Avenue, NW, Suite 1100, Washington, DC 20037 as a benefit of National Trust Forum The National Trust for Historic Preservation works to save America’s historic places for membership. -

Gerard & Kelly

Online Circulation: 9,900 FRIEZE / GERARD & KELLY / JULY 16, 2016 Gerard & Kelly By Evan Moffitt | July 16, 2016 The Glass House, New Canaan, Connecticut, USA The modernist philosophy of Le Corbusier, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and their contemporaries was demo- cratic and utopian – at least until it was realized in concrete, glass and steel. Despite its intention to pro- duce affordable designs for better living, modernism became the principle style for major corporations and government offices, for the architecture of capital and war. Are its original ideals still a worthy goal? I found myself asking that question at the Philip Johnson Glass House in New Canaan, Connecticut, while watch- ing Modern Living (2016), the latest work by performance artist duo Brennan Gerard and Ryan Kelly. As I followed the sloping path to Johnson’s jewel box, pairs of dancers dressed in colourful, loose-fitting garments, mimicking each other’s balletic movements, appeared in emerald folds of lawn. With no accompaniment but the chirping of birds and the crunch of gravel underfoot, I could’ve been watching tai chi at a West Coast meditation re- treat. The influence of postmodern California choreographers, such as the artists’ mentor Simone Forti, was clear. Gerard & Kelly, Modern Living, 2016, documentation of performance, The Glass House, New Canaan; pictured: Nathan Makolandra and Stephanie Amurao. Cour- tesy: Max Lakner/BFA.com When the Glass House was first completed in 1949, Johnson was criticised for producing a voyeuristic do- mestic space in an intensely private era governed by strict sexual mores. Like a fishbowl, the house gave its in- habitants nowhere to hide.