Ultra: I Was There Volume I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Georgetown University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Security Studies

THE BATTLE FOR INTELLIGENCE: HOW A NEW UNDERSTANDING OF INTELLIGENCE ILLUMINATES VICTORY AND DEFEAT IN WORLD WAR II A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Security Studies By Edward J. Piotrowicz III, B.A. Washington, DC April 15, 2011 Copyright 2011 by Edward J. Piotrowicz III All Rights Reserved ii THE BATTLE FOR INTELLIGENCE: HOW A NEW UNDERSTANDING OF INTELLIGENCE ILLUMINATES VICTORY AND DEFEAT IN WORLD WAR II Edward J. Piotrowicz III, B.A. Thesis Advisor: Jennifer E. Sims, PhD. ABSTRACT Does intelligence make a difference in war? Two World War II battles provide testing grounds for answering this question. Allied intelligence predicted enemy attacks at both Midway and Crete with uncanny accuracy, but the first battle ended in an Allied victory, while the second finished with crushing defeat. A new theory of intelligence called “Decision Advantage,”a illuminates how the success of intelligence helped facilitate victory at Midway and how its dysfunction contributed to the defeat at Crete. This view stands in contrast to that of some military and intelligence scholars who argue that intelligence has little impact on battle. This paper uses the battles of Midway and Crete to test the power of Sims‟s theory of intelligence. By the theory‟s standards, intelligence in the case of victory outperformed intelligence in the case of defeat, suggesting these cases uphold the explanatory power of the theory. Further research, however, could enhance the theory‟s prescriptive power. -

Connecticut English Gardens!

7/10/2015 Weekly Real Estate Hot List: Top Ten Home & Condos | Jul 07, 2015 Toggle navigation Top Ten Lists Top Ten Florida Condo Lists Florida New Condo Developments Florida Luxury Condos Florida PreConstruction Pompano Beach Condos For Sale Weekly Hot List News Agents Say What? In The Press View All Florida Condos For Sale Connecticut English Gardens! Connecticut English Gardens! New Canaan, Connecticut, a onehour commute from Manhattan, is a town with a lot of history. Always considered one of the wealthiest enclaves in the country, that reputation started when the first rail line came through and wealthy New Yorkers started building their summer mansions there. In time, they began living in New Canaan full time and commuting to Manhattan. It was a town of tradition and all that was old world until the modern explosion took place from the 1940s through the 1960s when the Harvard Five invaded the city. Young architects Philip Johnson, Marcel Breuer, Landis Gores, John M. Johansen and Eliot Noyes ascended and began building their “outlandish” homes. Fogies were in shock and horror as houses with great expanses of glass and open floor plans began popping up. There were eighty of these new fangled houses, twenty of which have now been torn down, that put New Canaan on the architectural map. The city has since been the setting for film, books and the home base of “preppy” style. http://www.toptenrealestatedeals.com/homes/weeklytenbesthomedeals/2015/772015/3/ 1/12 7/10/2015 Weekly Real Estate Hot List: Top Ten Home & Condos | Jul 07, 2015 Now for sale is a 15,000squarefoot English Arts and Crafts/American Shinglestyle residence on 3.71 acres with English gardens, swimming pool terrace, tennis court with viewing platform and a walled children’s playground. -

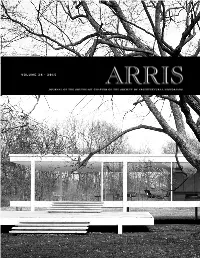

Architectural Photography, the Farnsworth House, and the Opaque Discourse of Transparency SARAH M

VOLUME 26 · 2015 JOURNAL OF THE SOUTHEAST CHAPTER OF THE SOCIETY OF ARCHITECTURAL HISTORIANS Volume 26 · 2015 1 Editors’ Note Articles 6 Madness and Method in the Junkerhaus: The Creation and Reception of a Singular Residence in Modern Germany MIKESCH MUECKE AND NATHANIEL ROBERT WALKER 22 Curtained Walls: Architectural Photography, the Farnsworth House, and the Opaque Discourse of Transparency SARAH M. DRELLER 40 The “Monster Problem”: Texas Architects Try to Keep it Cool Before Air Conditioning BETSY FREDERICK-ROTHWELL 54 Electrifying Entertainment: Social and Urban Modernization through Electricity in Savannah, Georgia JESSICA ARCHER Book Reviews 66 Cathleen Cummings, Decoding a Hindu Temple: Royalty and Religion in the Iconographic Program of the Virupaksha Temple, Pattadakal REVIEWED BY DAVID EFURD 68 Reiko Hillyer, Designing Dixie: Tourism, Memory, and Urban Space in the New South REVIEWED BY BARRY L. STIEFEL 70 Luis E, Carranza and Fernando L. Lara, Modern Architecture in Latin America: Art, Technology, and Utopia REVIEWED BY RAFAEL LONGORIA Field Notes 72 Preserving and Researching Modern Architecture Outside of the Canon: A View from the Field LYDIA MATTICE BRANDT 76 About SESAH ABSTRACTS Sarah M. Dreller Curtained Walls: Architectural Photography, the Farnsworth House, and the Opaque Discourse of Transparency Abstract This paper studies the creation, circulation, and reception of two groups of photographs of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s iconic Farnsworth House, both taken by Hedrich Blessing. The first set, produced for a 1951 Architectural Forum magazine cover story, features curtains carefully arranged according to the architect’s preferences; the Museum of Modern Art commis- sioned the second set in 1985 for a major Mies retrospective exhibition specifically because the show’s influential curator, Arthur Drexler, believed the curtains obscured Mies’ so-called “glass box” design. -

Street & Number 192 Cross Ridge Road___City Or Town New

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) RECEIVED 2280 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service FR 2002 National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete me '" '"'' National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item be marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable". For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items. 1. Name of Property_________________________________________________ historic name LANDIS GORES HOUSE other names/site number N/A 2. Location street & number 192 Cross Ridge Road_________ D not for publication city or town New Canaan________________ _______ D vicinity state Connecticut code CT county Fairfield code 001 zip code .06840. 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this Kl nomination D request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property H meets D does not meet the National Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant DnationaJly-C§ statewide D locally.^£]J5ee continuation sheet for additional comments.) February 4, 2002 Decertifying offfoffirritle ' Date Fohn W. -

Miller House, Orange New Haven County, Connecticut

Henry F. Miller House, Orange New Haven County, Connecticut I, hereby certify that this property is i/ entered in the National Register __ See continuation sheet. ___ determined eligible for the National Register __ See continuation sheet. ___ determined not eligible for the National Register removed from the National Register other (explain): M______ l^ighature of Keeper Date of Action 5. Classification Ownership of Property (Check as many boxes as apply) X private __ public-local __ public-State __ public-Federal Category of Property (Check only one box) X building(s) __ district site structure object Number of Resources within Property: Contributing Noncontributing 1 ____ buildings ____ ____ sites 1 ____ structures ____ ____ objects 2 0 Total Number of contributing resources previously listed in the National Register: _0 Name of related multiple property listing: N/A 6. Function or Use Historic Functions (Enter categories from instructions) Cat: DOMESTIC_______________ Sub: ____single dwelling Current Functions (Enter categories from instructions Henry F. Miller House, Orange New Haven County, Connecticut Cat: DOMESTIC Sub: single dwelling 7. Description Architectural Classification: ___International Stvle Materials: foundation poured concrete roof built-up walls concrete block; vertical tongue and groove fir sidincr other Narrative Description Describe present and historic physical appearance, X See continuation sheet. NFS Form 10-900-a 0MB No. 1024-0018 (8-86) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES CONTINUATION SHEET Description Henry F. Miller House, Orange 7-1 New Haven County, CT Narrative Description The Henry F. Miller House is an International Style structure built in 1949 and located on a wooded hillside in the town of Orange, Connecticut. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. 1. Name of Property Historic name: __Norwich Mid-Century Modern Historic District_______ Other names/site number: ______________________________________ Name of related multiple property listing: _N/A__________________________________________________________ (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing ____________________________________________________________________________ 2. Location Street & number: Parts of Hopson Road, Pine Tree Road, & Spring Pond Road___________ City or town: __Norwich__ State: _Vermont__ County: __Windsor__ Not For Publication: Vicinity: _____________________________________________________________________ _______ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties -

Polish Mathematicians Finding Patterns in Enigma Messages

Fall 2006 Chris Christensen MAT/CSC 483 Machine Ciphers Polyalphabetic ciphers are good ways to destroy the usefulness of frequency analysis. Implementation can be a problem, however. The key to a polyalphabetic cipher specifies the order of the ciphers that will be used during encryption. Ideally there would be as many ciphers as there are letters in the plaintext message and the ordering of the ciphers would be random – an one-time pad. More commonly, some rotation among a small number of ciphers is prescribed. But, rotating among a small number of ciphers leads to a period, which a cryptanalyst can exploit. Rotating among a “large” number of ciphers might work, but that is hard to do by hand – there is a high probability of encryption errors. Maybe, a machine. During World War II, all the Allied and Axis countries used machine ciphers. The United States had SIGABA, Britain had TypeX, Japan had “Purple,” and Germany (and Italy) had Enigma. SIGABA http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SIGABA 1 A TypeX machine at Bletchley Park. 2 From the 1920s until the 1970s, cryptology was dominated by machine ciphers. What the machine ciphers typically did was provide a mechanical way to rotate among a large number of ciphers. The rotation was not random, but the large number of ciphers that were available could prevent depth from occurring within messages and (if the machines were used properly) among messages. We will examine Enigma, which was broken by Polish mathematicians in the 1930s and by the British during World War II. The Japanese Purple machine, which was used to transmit diplomatic messages, was broken by William Friedman’s cryptanalysts. -

Idle Motion's That Is All You Need to Know Education Pack

Idle Motion’s That is All You Need to Know Education Pack Idle Motion create highly visual theatre that places human stories at the heart of their work. Integrating creative and playful stagecraft with innovative video projection and beautiful physicality, their productions are humorous, evocative and sensitive pieces of theatre which leave a lasting impression on their audiences. From small beginnings, having met at school, they have grown rapidly as a company over the last six years, producing five shows that have toured extensively both nationally and internationally to critical acclaim. Collaborative relationships are at the centre of all that they do and they are proud to be an Associate Company of the New Diorama Theatre and the Oxford Playhouse. Idle Motion are a young company with big ideas and a huge passion for creating exciting, beautiful new work. That is All You Need to Know ‘That Is All You Need To Know’ is Idle Motion’s fifth show. We initially wanted to make a show based on the life of Alan Turing after we were told about him whilst researching chaos theory for our previous show ‘The Seagull Effect’. However once we started to research the incredible work he did during the Second World War at Bletchley Park and visited the site itself we soon realised that Bletchley Park was full of astounding stories and people. What stood out for us as most remarkable was that the thousands of people who worked there kept it all a secret throughout the war and for most of their lives. This was a story we wanted to tell. -

Confronting Privilege and Possibility at SANAA's Grace Farms

The Avery Review Sam holleran – Estate of Grace: Confronting Privilege and Possibility at SANAA’s Grace Farms New Canaan, Connecticut, has long been conflated with the WASPy ur-’burb Citation: Sam Holleran, “Estate of Grace: Confronting Privilege and Possibility at SANAA’s Grace Farms,” depicted in Rick Moody’s 1994 novel-turned-film The Ice Storm: popped in The Avery Review, no. 13 (February 2016), http:// collars, monogrammed bags, and picket fences. This image has been hard to averyreview.com/issues/13/estate-of-grace. shake for this high-income town at the end of a Metro-North rail spur, which is, to be sure, a comfortable place to live—far from the clamor of New York City but close to its jobs (and also reasonably buffered from the poorer, immi- grant-heavy pockets of Fairfield County that line Interstate 95). This community of 20,000 is blessed with rolling hills, charming historic architecture, and budgets big enough for graceful living. Its outskirts are latticed with old stone walls and peppered with luxe farmhouses and grazing deer. The town’s center, or “village district,” is a compact two-block elbow of shops that hinge from the rail depot (the arterial connection to New York City’s capital flows). Their exteriors are municipally regulated by Design Guidelines mandating Colonial building styles—red brick façades with white-framed windows, low-key signage, and other “charm-enhancing” elements. [1] The result is a New Urbanist core [1] The Town of New Canaan Village District Design Guidelines “Town of New Canaan Village District that is relatively pedestrian-friendly and pleasant, if a bit stuffy. -

CT Fairfieldco Stmarksepiscop

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. 1. Name of Property Historic name: __St. Mark’s Episcopal Church________________________ Other names/site number: ______________________________________ Name of related multiple property listing: ___N/A________________________________________________________ (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing ____________________________________________________________________________ 2. Location Street & number: _111 Oenoke Ridge___________________________________ City or town: _New Canaan_____ State: _Connecticut______ County: _Fairfield______ Not For Publication: Vicinity: __________________________________________________________________ __________ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties -

2009 2 March

Connecticut Preservation News March/April 2009 Volume XXXII, No. 2 C. Wigren C. courtesy of Elizabeth Mills Brown Elms on the Rebound nce upon a time, Connecticut towns and cities were It wasn’t always so. For the first European settlers, trees were graced by hundreds, even thousands, of American obstacles to be removed before they could build towns, graze O th th elm trees. By the second half of the 19 century elms had become animals, or plant crops. Only at the end of the 18 century, after a defining characteristic of New England villages, their grace- the initial clearing had been accomplished and Romanticism fully drooping branches making the streets sheltered, but still inspired a new attitude toward Nature as nurturer rather than open and inviting, corridors of space. Invariably they inspired opponent, did New Englanders begin planting trees for orna- visitors’ comments; as one Rhode Island resident remembered, ment. It began with public-spirited individuals such as James “When you came into any town in New England the landscape Hillhouse of New Haven, who initiated efforts to plant trees on changed; you entered this kind of forest with 100-foot arches. the New Haven Green and then throughout the city (actually The shadows changed. Everything seemed very reverent, there planting many of them himself, according to legend). By mid- was a certain serenity, a certain calmness… a sweetness in the air. century, village improvement societies throughout the region It was an otherworldly experience, you knew you were entering had taken up the cause, incorporating tree-planting in their an almost sacred place.” improvement programs. -

Gerard & Kelly

Online Circulation: 9,900 FRIEZE / GERARD & KELLY / JULY 16, 2016 Gerard & Kelly By Evan Moffitt | July 16, 2016 The Glass House, New Canaan, Connecticut, USA The modernist philosophy of Le Corbusier, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and their contemporaries was demo- cratic and utopian – at least until it was realized in concrete, glass and steel. Despite its intention to pro- duce affordable designs for better living, modernism became the principle style for major corporations and government offices, for the architecture of capital and war. Are its original ideals still a worthy goal? I found myself asking that question at the Philip Johnson Glass House in New Canaan, Connecticut, while watch- ing Modern Living (2016), the latest work by performance artist duo Brennan Gerard and Ryan Kelly. As I followed the sloping path to Johnson’s jewel box, pairs of dancers dressed in colourful, loose-fitting garments, mimicking each other’s balletic movements, appeared in emerald folds of lawn. With no accompaniment but the chirping of birds and the crunch of gravel underfoot, I could’ve been watching tai chi at a West Coast meditation re- treat. The influence of postmodern California choreographers, such as the artists’ mentor Simone Forti, was clear. Gerard & Kelly, Modern Living, 2016, documentation of performance, The Glass House, New Canaan; pictured: Nathan Makolandra and Stephanie Amurao. Cour- tesy: Max Lakner/BFA.com When the Glass House was first completed in 1949, Johnson was criticised for producing a voyeuristic do- mestic space in an intensely private era governed by strict sexual mores. Like a fishbowl, the house gave its in- habitants nowhere to hide.