Bulletin of the GHI Washington

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Review of Restrictions and PVC Free Policies Worldwide

PVC-Free Future: A Review of Restrictions and PVC free Policies Worldwide A list compiled by Greenpeace International 9th edition, June 2003 © Greenpeace International, June 2003 Keizersgracht 176 1016 DW Amsterdam The Netherlands Tel: +31 20 523 6222 Fax: +31 20 523 6200 Web site: www.greenpeace.org/~toxics If your organisation has restricted the use of Chlorine/PVC or has a Chlorine/PVC-free policy and you would like to be included on this list, please send details to the Greenpeace International Toxics Campaign 1 Contents 1. Political......................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 International Agreements on Hazardous Substances............................. 4 Mediterranean........................................................................................................... 4 North-East Atlantic (OSPAR & North Sea Conference)..................................... 4 International Joint Commission - USA/Canada................................................... 6 United Nations Council on Environment and Development (UNCED)............ 7 United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP).............................................. 7 UNEP – global action on Persistent Organic Pollutants..................................... 7 UNIDO........................................................................................................................ 8 1.2 National PVC & Chlorine Restrictions and Other Initiatives: A-Z.......10 Argentina..................................................................................................................10 -

Specialized for Powerful Solutions Specialized for Powerful Solutions

Machines and services for the wire industry TAKE UP SERIES Advice Engineering Design work Machinery delivery Commissioning Training specialized for powerful solutions schmidt Maschinenbau GmbH Machines for the wire industry After the drawing process, the wire needs to anneal in order to achieve the requested material properties. Schmidt has developed a wide range of sophisticated state-of-the-art take-ups for this kind of annealing pro- cesses. The modular line concept gives the opportunity to defi ne the machine capabilities in accordance to the actual need. FEATURES AND BENEFITS • Traversing spool for best spooling results • Spooling tension measurement and control for supervised quality • Supervision of all controlled values, with trend feature and historical data • Modular design, each line comes with its own control and operation panel • Optimal design with minimal wire bending • Low energy consumption due to modern stepping motor drives • Scalable units for diff erent wire ranges FINE WIRE TAKE-UP Type SM36 Wire diameter From 0.01 to 0.08 mm (.0004” to .0032”) FEATURES AND BENEFITS Annealing take-up designed for ultra-fi ne wire 10 µm to 80 µm. production speed up to 300 m/min. • Capstan and spreader disc with ceramic layer from Chrome Oxide • Traversing spool, guiding pulley adjustable for easy centring of the spooling • Both spool rims adjustable by operation panel buttons • Spooler shaft Ø 16 mm (.63”), spool adapter for spool type HK100 and HK130 • Spooling tension controlled and supervised via tension-measurement device at guiding -

Der Oberbergische Kreis Auf Einen Blick

Der Oberbergische Kreis auf einen Blick Der dem nördlichen rechtsrheinischen Schiefergebirge zugehörige Oberbergische Kreis ist ein Übergangsgebiet zwischen der Talebene des Rheins und dem sauerländischen Bergland. Das Gummersbacher Bergland in der Kreismitte bildet den höchsten Teil des Bergischen Landes. Dort sind zugleich die Quellgebiete der Agger und der Wupper. Schwerpunkte verdichteter Siedlung liegen in den industriedurchsetzten Tälern. In seiner derzeitigen Form entstand der Oberbergische Kreis durch die kommunale Neugliederung zum 1.1.1975. Er zeichnet sich in besonde- rer Weise durch landschaftlichen Zusammenhang, Einheitlichkeit der Siedlungsstruktur und gemeinsame historische Beziehungen aus. Die aktuellen Berufspendlerverflechtungen weisen den Kreis als eigenstän- digen Wirtschaftsraum aus. Oberberg ist zwar Teil des hochverdichte- ten Agglomerationsraumes an Rhein und Ruhr, weist jedoch deutlich andere Strukturen auf als die ballungskernnahen Kreise. Derzeit hat der Oberbergische Kreis bei einer Fläche von gut 918 km² rund 290.000 Einwohner. Die Industrie ist mittelständisch. Maschinen- bau, Fahrzeugbau, Edelstahlerzeugung, Stahl- und Leichtmetallbau, Eisen-, Blech- und Metallverarbeitung, Elektrotechnische Industrie und Kunststoffverarbeitung sind die wichtigsten Branchen. Prognosen las- sen bis 2010 weiteres Wachstum an Einwohnern und Arbeitsplätzen erwarten. Als zentraler Bestandteil des Naturparks Bergisches Land ist der Kreis Ziel von zahlreichen Erholungssuchenden. Wichtiger Standortfaktor ist die Abteilung Gummersbach der Fachhoch- schule Köln. Sie hat ein für die Wirtschaft in Oberberg sehr leistungsfä- higes Fächerspektrum. In den Standort eingebunden ist ein Studien- zentrum der Fernuniversität Hagen. Die Verkehrsverbindungen nach Köln (RB 25 'Oberbergische Bahn' und BAB A 4) und in Nord-Süd-Richtung (BAB A 45) sind gut. Die für 2005 vorgesehene Weiterführung der RB 25 bis Lüdenscheid stellt eine we- sentliche Verbesserung der Anbindung an den nord- und mitteldeut- schen Raum dar. -

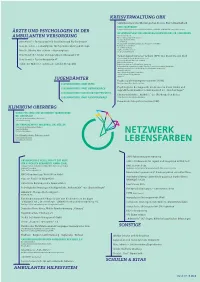

Kreisverwaltung Obk

KREISVERWALTUNG OBK Sozialdezernent des Oberbergischen Kreises, Herr Schmallenbach KREISJUGENDAMT ÄRZTE UND PSYCHOLOGEN IN DER Bergneustadt/Engelskirchen/Lindlar/Marienheid/Morsbach/Nümbrecht/Waldbröl/Reichshof/Hückeswagen GESUNDHEITSAMT DES OBERBERGISCHEN KREISES, FR. ELVERMANN Amtsärztlicher Dienst AMBULANTEN VERSORGUNG Kinder- und Jugendgesundheitsdienst Sozialpsychiatrischer Dienst Herr Althoff > Facharztpraxis für Psychiatrie und Psychotherapie Soziale Dienste Beratungsstelle für Familienplanung und Schwangerschaftskonflikte Frau Dr. Frohne > Facharztpraxis für Psychiatrie und Psychotherapie Kommunaler sozialer Dienst Gesundheitsförderung Projekt „Verrückt? Na und?“ Herr Dr. Olbeter, Herr Stüttem > Hausarztpraxis Pilotprojekt Familienpaten Frau Wendrich > Kinder und Jugendpsychotherapeutin VT Gemeindepsychiatrischen Verbund (GPV) Süd, Kreismitte und Nord Caritasverband für den Oberbergischen Kreis e.V. Frau Korneli > Psychotherapeutin VT Curt-von-Knobelsdorff-Haus Radevormwald Diakonie Michaelshoven Sabine zur Mühlen > systemische Familientherapeutin Diakonisches Werk des Ev. Kirchenkreises Lennep e.V. Kreiskrankenhaus Gummersbach GmbH / Zentrum für Seelische Gesundheit Marienheide Oberbergische Gesellschaft zur Hilfe für psychisch Behinderte GmbH (OGB) Oberbergischer Kreis RAPS Gemeinnützige Werkstätten GmbH Theodor Fliedner Stiftung, Waldruhe JUGENDÄMTER Alpha e.V. Psychosoziale Arbeitsgemeinschaften (PSAG) JUGENDAMT DER STADT WIEHL Kinder und Jugendliche/Erwachsene/Sucht Psychologische Beraungsstelle des Kreises für Eltern, Kinder -

Kommunalprofil Marienheide Oberbergischer Kreis, Regierungsbezirk Köln, Gemeindetyp: Größere Kleinstadt

Information und Technik Nordrhein-Westfalen Statistisches Landesamt Kommunalprofil Marienheide Oberbergischer Kreis, Regierungsbezirk Köln, Gemeindetyp: Größere Kleinstadt Inhalt: Fläche Bevölkerung Bevölkerungsvorausberechnung Bevölkerungsbewegung Bildung Schwerbehinderte Menschen Sozialversicherungpflichtig Beschäftige Verarbeitendes Gewerbe Investitionen im Verabeitenden Gewerbe Bauhauptgewerbe Gewerbean- und -abmeldungen Einkommen Verkehr Wahlen Weitere Informationen finden Sie in unserer Landesdatenbank unter www.landesdatenbank.nrw.de Zentrale Information und Beratung Telefon: 0211 9449-2495/2525 E-Mail: [email protected] www.it.nrw Kommunalprofil Marienheide 2/25 Für die Klassifikation der Kommunen nach Gemeindetypen wird eine Gemeindereferenz des Bundesamtes für Bauwesen und Raumordnung mit nachfolgender Definition verwendet (Stand: 2012): Gemeindetyp Definition Große Großstadt Großstädte um 500 000 Einwohner und mehr Kleine Großstadt Großstädte unter 500 000 Einwohner Große Mittelstadt Mittelstädte mit Zentrum, 50 000 Einwohner und mehr Kleine Mittelstadt Mittelstädte mit Zentrum, 20 000 bis 50 000 Einwohner Größere Kleinstadt Kleinstädte mit Zentrum, 10 000 Einwohner und mehr Kleine Kleinstadt Kleinstädte mit Zentrum, 5 000 bis 10 000 Einwohner oder Grundzentrale Funktion Dem Gemeindetyp „Größere Kleinstadt“ sind folgende Kommunen zugeordnet: Aldenhoven Hille Olfen, Stadt Alpen Holzwickede Olsberg, Stadt Altena, Stadt Horn-Bad Meinberg, Stadt Ostbevern Altenberge Hörstel, Stadt Preußisch Oldendorf, Stadt Anröchte Hövelhof -

Nachname Vorname Wohnort Gemeinde/Stadt Adsiz Acelya

Nachname Vorname Wohnort Gemeinde/Stadt Adsiz Acelya Gummersbach Aklan Selin Rodt Marienheide Altergott Julia Gummersbach Altjohann Martin-Uwe Gummeroth Gummersbach Anders Tizian Derschlag Gummersbach Appel Anna Katharina Hesselbach Gummersbach Banaschewitz Moritz Strombach Gummersbach Bartz Zoe Bernadette Gummersbach Bartz Leon Alexander Gummersbach Becher Chiara Caterina Niederseßmar Gummersbach Beck Joel Rodt Marienheide Becker Celina Michelle Dümmlinghausen Gummersbach Bekiaroudi Luana Konstantina Windhagen Gummersbach Bemelmann Dania Alferzhagen Wiehl Berger Colin Marienheide Beydoun Zena Hesselbach Gummersbach Binder Maximilian Steinberg Gummersbach Brand Lukas Gummersbach Brock Sebastian Bielstein Wiehl Budde Sara-Lena Hardt Gummersbach Burnic Elmedin Wiedenest Bergneustadt Buttstädt Linda Bredenbruch Gummersbach Daugy Hannah Ründeroth Engelskirchen de Lara Alyssa Steinenbrück Gummersbach Derksen Sam Mittelagger Reichshof Di Blasi Laura Celina Kalsbach Marienheide Dick Daniel Gummersbach Dieckmann Maya Elbach Gummersbach Dohrmann Nils Bernberg Gummersbach Dreier Jenny Helena Karlskamp Gummersbach Dröscher Anja Sophie Gummersbach Drumm Nina Sophie Derschlag Gummersbach Dziubek Senta Laura Gummersbach Eschbach Jan Arne Becke Gummersbach Farsch Lara Jill Gummersbach Feld Kai Windhagen Gummersbach Ferdinand Chantal Julia Gummersbach Fischer Jennifer Bernberg Gummersbach Förster Linus Gummersbach Franken Michelle Windhagen Gummersbach Fritsche Lea Melina Hesselbach Gummersbach Funke Anna Eckenhagen Reichshof Gensow Tom Karlskamp Gummersbach -

Grundstücksmarktbericht 2020 Für Den Oberbergischen Kreis

Der Gutachterausschuss für Grundstückswerte im Oberbergischen Kreis Grundstücksmarktbericht 2020 für den Oberbergischen Kreis www.boris.nrw.de Der Gutachterausschuss für Grundstückswerte im Oberbergischen Kreis Grundstücksmarktbericht 2020 Berichtszeitraum 01.01.2019 – 31.12.2019 Übersicht über den Grundstücksmarkt im Oberbergischen Kreis Herausgeber Der Gutachterausschuss für Grundstückswerte im Oberbergischen Kreis Geschäftsstelle Fritz-Kotz-Str. 17 a 51674 Wiehl Telefon: 02261-88 6279 Fax: 02261-88 972 8062 E-Mail: [email protected] Internet: www.obk.de/gutachterausschuss Druck Oberbergischer Kreis Gebühr Das Dokument kann unter www.boris.nrw.de gebührenfrei heruntergeladen werden. Bei einer Bereitstellung des Dokuments oder eines gedruckten Exemplars durch die Geschäftsstelle des Gutachterausschusses beträgt die Mindestgebühr 23 EUR (Nr. 5.3.2.2 des Gebührentarifs der Kostenordnung für das amtliche Vermessungswesen und die amtliche Grundstückswertermittlung in Nordrhein-Westfalen). Bildnachweis © Geschäftsstelle des Gutachterausschusses für Grundstückswerte im Oberbergischen Kreis Lizenz Für den Grundstücksmarktbericht gilt die Lizenz "Datenlizenz Deutschland - Zero - Version 2.0" (dl-de/zero-2-0). Jede Nutzung ist ohne Einschränkungen oder Bedingungen zulässig. Sie können den Lizenztext unter www.govdata.de/dl-de/zero-2-0 einsehen. PDF erzeugt am 12.05.2020 ISSN: 2569-9164 Grundstücksmarktbericht des Oberbergischen Kreis 2020 5 Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 Gutachterausschüsse und ihre Aufgaben 9 1.1 Zuständigkeitsbereich des örtlichen -

Rad- Und E-Bikeroute Wasserquintett

Rad- und E-Bikeroute Wasserquintett Streckenkurzbeschreibung Ausgangspunkte der Radtour Wasserquintett Pauschalangebot Impressum: Bergische Wandergastronomie Kontakt und Service: Die Gesamtstrecke von ca. 80 km Länge lässt sich in Die Stadt Hückeswagen, im Tal der Wupper gelegen, hat Die vier Kommunen Hückeswagen, Radevormwald, » Begrüßungsgetränk www.bergische-wandergastronomie.de mehreren Teiletappen erradeln. Ein Einstieg kann in eine über 900-jährige Geschichte. Besonders sehenswert ist Wipperfürth, Marienheide und der Wupperverband [email protected] » Übernachtung im DZ jeder der vier Städte erfolgen (s. Städtebeschreibung – die historische Altstadt mit dem Schloss. Im Schloss ist auch arbeiten in enger Kooperation mit dem Oberbergi- www.naturarena.de Ausgangspunkt). das Heimatmuseum untergebracht. schen Kreis am Projekt „Wasserquintett“ zusammen. » Vital-Frühstück [email protected] Ausgangspunkt der Radroute ist der Wanderparkplatz an Telefon: 02266 – 463370 Ausgangspunkt der Strecke kann z.B. der DB » Lunchpaket der Wuppervorsperre „Am Mühlenweg“. Das Wasserquintett ist ein Projekt der Regionale 2010 Anschluss Marienheide sein. Hier kann man sich Beteiligte: und ist im Projektbereich: grün angesiedelt. Das Zu- » 3-Gang Abendessen entscheiden, ob man die Route direkt Richtung Stadt Hückeswagen www.hueckeswagen.de kunftsbild der einzigartigen Talsperrenlandschaft soll im » Gepäcktransfer Wipperfürth oder erst die Route über die beiden Die Gemeinde Marienheide verfügt als einzige Gemeinde Marienheide www.marienheide.de interkommunalen Handeln entwickelt werden, deren Talsperren Brucher und Lingese nimmt. Kommune im Wasserquintett über einen Bahnanschluss » Hilfe bei der Strecke, leihweise Radfahrkarte Stadt Radevormwald www.radevormwald.de (Citybahn Marienheide-Köln). Interessant ist vor allem signifikante Ausgangspunkte in der Wasser-, Natur- und Stadt Wipperfürth www.wipperfuerth.de Von Marienheide zur Brucher-Talsperre, entlang die Klosteranlage mit Wallfahrts- und Klosterkirche aus Kulturgeschichte liegen. -

17.02.2021: Coronavirus: 26 Weitere Fälle Im Kreisgebiet Bestätigt

PRESSEMITTEILUNG [[NeuerBrief]] OBERBERGISCHER KREIS | DER LANDRAT | 51641 Gummersbach Kommunikation und Öffentlichkeitsarbeit Moltkestraße 42 51643 Gummersbach Kontakt: Jessica Schöler Zimmer-Nr.: A1-23 Mein Zeichen: - Telefon: 02261 88-1215 Fax: 02261 88-972-1215 www.obk.de Steuer-Nr. 212/5804/0178 USt.-ld.Nr. DE 122539628 Datum: 17.02.2021 17.02.2021: Coronavirus: 26 weitere Fälle im Kreisgebiet bestätigt Derzeit sind 289 Personen aus dem Oberbergischen Kreis positiv auf SARS-CoV- 2 getestet. Oberbergischer Kreis. Seit der gestrigen Berichterstattung wurden 26 weitere Personen aus dem Oberbergischen Kreis positiv auf SARS-CoV-2 getestet (laborbestätigte Fälle). Seit Beginn der Pandemie wurden im Oberbergischen Kreis 8.163 Personen positiv auf SARS-CoV-2 getestet (laborbestätigte Fälle). Davon konnten bereits 7.725 Personen als genesen aus der Quarantäne entlassen werden. Aktuell sind 289 Personen positiv auf das Virus getestet (laborbestätigte Fälle). Es werden derzeit 59 Personen stationär in Krankenhäusern behandelt, die positiv auf SARS-CoV-2 getestet worden sind. Sieben der 59 stationär behandelten Personen werden derzeit beatmet. Alle positiv getesteten Personen befinden sich in angeordneter Quarantäne. Es ist eine weitere Person aus dem Oberbergischen Kreis verstorben, die zuvor positiv auf SARS-CoV-2 getestet worden war. Verstorben ist ein 59-jähriger Mann aus Morsbach. Seit Beginn der Pandemie sind im Oberbergischen Kreis 149 Personen verstorben, die zuvor positiv auf das Virus getestet worden waren. Allgemeinverfügungen zur Quarantäneanordnung Unter www.obk.de/corona-av erhalten Sie die Auflistung der aktuell gültigen Allgemeinverfügungen zur Quarantäneanordnung für Kontaktpersonen in oberbergischen Einrichtungen. Die Auflistung wird fortlaufend ergänzt. Hinweise zur elektronischen Kommunikation: www.obk.de/emails | Weitere Hinweise unter: www.obk.de Seite 1 von 4 Nachweis von Virusmutanten im Kreisgebiet Das Gesundheitsamt des Oberbergischen Kreises übersendet Proben zur Typisierung an Labore. -

Busnetz Oberbergischer Kreis 2021

Brombacher Berg A 6 Fritz-Kotz-Str. D 6 Hanfgarten D 5 HALTESTELLENVERZEICHNIS Bruch B 1 E Frösseln A 3 Hardt (Engelskirchen) B/C 5 Brüchermühle E 7 Eckenhagen E/F 5/6 Fuchs E 2 Hardt (Gummersbach) F 3 Brück D 6 Eckenhagen Kurpark E 5/6 Fürden B 3 Hardtstr. D 5 Brückenstr. D 4 Egen B 1 Furth B 3 Harhausen C 2 Bech Abzw. D 9 Egerpohl C 2 Liniennetz Brünglinghausen Abzw. E 8 Harscheid D 8 A Bellingroth C 6 Brunohl C 5 Eibachstr. B 4 G Hartegasse B 4 Achsenfabrik D 6 Belmicke F 4 Buch E 8 Eich F 1/2 Gaderoth E 7 Hasenbach E 7 Aggerbrücke C 5 Benroth D 9 Buchen (Karte) F 6 Eichhardtstr. D 6 Gardeweg C 1 Hasenburg Abzw. B 1 Oberbergischer Kreis Aggertalhöhle C 5 Bergerhof (Radevormwald) E 2 Büchlerhausen C 5 Eichholz B 4/5 Gaultal Center B/C 2 Haus Echo D 6 Ahe B 3 Bergerhof (Reichshof) F 7 Bühlstahl C 3 Eichholz Ort B 4/5 Gemeindezentrum E 3 Heckelsiefen E 6 Ahlbusch D 8 Bergerhof Abzw. F 7 Burgbergstr. D 5 Eisenstr. (Kohlberg) E 9 Genkeltalsperre E 4 Heerschlade E 6 Ahlefeld D 5 Berghausen (Gummersbach) C 4 Burgmühle E 6 Eistringhausen Abzw. F 1 Georghausen A 5 Heibach B 4 Ahlefelder Str. D 5 Berghausen (Morsbach) F 8 Burgstr. D 3 EKZ D 4 Gerhardsiefen Abzw. D 7 Heidberg F 6 2021 Ahlhausen B 1 Berghausen (Reichshof) E 6 Burstenstr. E 5 EKZ Baumhof D 4 Geringhausen Abzw. D 8 Heidberger Str. -

Home to the Reich: the Nazi Occupation of Europe's Influence on Life Inside Germany, 1941-1945

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 8-2015 Home to the Reich: The Nazi Occupation of Europe's Influence on Life inside Germany, 1941-1945 Michael Patrick McConnell University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation McConnell, Michael Patrick, "Home to the Reich: The Nazi Occupation of Europe's Influence on Life inside Germany, 1941-1945. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2015. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/3511 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Michael Patrick McConnell entitled "Home to the Reich: The Nazi Occupation of Europe's Influence on Life inside Germany, 1941-1945." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in History. Vejas Liulevicius, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Denise Phillips, Monica Black, Daniel Magilow Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) Home to the Reich: The Nazi Occupation of Europe’s Influence on Life inside Germany, 1941-45 A Dissertation Presented for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Michael Patrick McConnell August 2015 Copyright © 2015 by Michael McConnell All rights reserved. -

Invitation 21X21 Cm RZ.Indd

INVITATION TO OUR GOLDEN JUBILEE 50 years of IBZ Gimborn Castle Under the patronage of Herbert Reul, Minister of the Interior of North Rhine-Westphalia We would like to celebrate our success together with you – we look forward to seeing you! 30th and 31th August 2019 Schlossstraße 10 in 51709 Marienheide, Germany Kindly RSVP before 15.07.2019: phone +49-2264-404330 or email [email protected] JUBILEE PROGRAMME FRIDAY, 30.08.2019 Arrival of guests; starting at 6 pm, BBQ with music & dancing in the Castle Park SATURDAY, 31.08.2019 11 am Golden Jubilee Opening Ceremony with the State Police Orchestra of NRW 1 pm Champagne Reception & midday refreshments „ 2 pm Experience the Police“ – Blue Lights Day in Gimborn for young & old 7 pm Gala Evening with live music from the founding years of „ Cat Lee King & The Cocks“ SUNDAY, 01.09.2019 Departure of guests COVER CHARGE FRIDAY + SATURDAY incl. barbecue, Champagne reception & refreshments, gala dinner buffet € 60.00 per person plus beverages SATURDAY incl. Champagne reception & refreshments, gala dinner buffet € 40.00 per person plus beverages AccOMMODATION OPTIONS HOTEL ENGELSKIRCHEN Gelpestraße 1, 51766 Engelskirchen Phone +49-2263-3704, fax +49-2263-92 94 250 [email protected], www.hotel-restaurant-engelskirchen.de Due to the limited availability of Single - € 55.00, double - € 70.00 accommodation in Gimborn we have reserved a number of rooms MONTANA HOTEL GUMMERSBACH-NORD in hotels nearby. We kindly request you make your arrangements in Friesenstraße 8, 51709 Marienheide good time directly with the hotel of Phone +49-2264-270, fax +49-2264-2788 your choice.