RISK ASSESSMENT for EXOTIC REPTILES and AMPHIBIANS INTRODUCED to AUSTRALIA – Pond Slider (Trachemys Scripta) (Schoepff, 1792)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Competing Generic Concepts for Blanding's, Pacific and European

Zootaxa 2791: 41–53 (2011) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2011 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) Competing generic concepts for Blanding’s, Pacific and European pond turtles (Emydoidea, Actinemys and Emys)—Which is best? UWE FRITZ1,3, CHRISTIAN SCHMIDT1 & CARL H. ERNST2 1Museum of Zoology, Senckenberg Dresden, A. B. Meyer Building, D-01109 Dresden, Germany 2Division of Amphibians and Reptiles, MRC 162, Smithsonian Institution, P.O. Box 37012, Washington, D.C. 20013-7012, USA 3Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract We review competing taxonomic classifications and hypotheses for the phylogeny of emydine turtles. The formerly rec- ognized genus Clemmys sensu lato clearly is paraphyletic. Two of its former species, now Glyptemys insculpta and G. muhlenbergii, constitute a well-supported basal clade within the Emydinae. However, the phylogenetic position of the oth- er two species traditionally placed in Clemmys remains controversial. Mitochondrial data suggest a clade embracing Actinemys (formerly Clemmys) marmorata, Emydoidea and Emys and as its sister either another clade (Clemmys guttata + Terrapene) or Terrapene alone. In contrast, nuclear genomic data yield conflicting results, depending on which genes are used. Either Clemmys guttata is revealed as sister to ((Emydoidea + Emys) + Actinemys) + Terrapene or Clemmys gut- tata is sister to Actinemys marmorata and these two species together are the sister group of (Emydoidea + Emys); Terra- pene appears then as sister to (Actinemys marmorata + Clemmys guttata) + (Emydoidea + Emys). The contradictory branching patterns depending from the selected loci are suggestive of lineage sorting problems. Ignoring the unclear phy- logenetic position of Actinemys marmorata, one recently proposed classification scheme placed Actinemys marmorata, Emydoidea blandingii, Emys orbicularis, and Emys trinacris in one genus (Emys), while another classification scheme treats Actinemys, Emydoidea, and Emys as distinct genera. -

Ecology of the River Cooter, Pseudemys Concinna, in a Southern Illinois Floodplain Lake

He!peto!ogica! Nalllral Historv, 5(2), 1997, pages 135-145. 135 ©1997 by the International Herpetological Symposium. Inc. ECOLOGY OF THE RIVER COOTER, PSEUDEMYS CONCINNA, IN A SOUTHERN ILLINOIS FLOODPLAIN LAKE Michael J. Dreslikl Department of Zoology, Eastern Illinois University, Charleston, Illinois 61920, USA Abstract. In Illinois, the river cooter, Pseudemys concinna. is a poorly studied endangered species. During 1994-1996. I quantified growth, population size and structure. and diet of a population from a floodplain lake in Gallatin County, Illinois. For males and females. growth slowed between 8-15 and 13-24 years, respectively. Comparisons between male and female curves revealed that growth parameters and proportional growth toward the asymptote were not significantly different, while asymptotes differed significantly. Differences of scute ring- and Sexton-aged individuals from von Bertalanffy model estimates were not significant through age five for males and six for females. I estimated that 153, !57, and 235 individuals were found in the lake at densities of 5.1, 5.2, and 7.8 turtles/ha in 1994. 1995, and 1996, respectively. Associated biomass estimates were 3.84, 3.94, and 5.90 kg/ha, respectively. The overall sex ratio was female-biased, whereas the adult sex ratio was male-biased; both were not significantly different from equality. Key Words: Population ecology: Growth: Diet: Population structure; Tcstudines; Emydidae: Pseudemys concinna. Ecological studies can elucidate specific life its state-endangered status in Illinois (Herkert history traits which can be utilized in conservation 1992), and because of the scarcity of information and management planning. Many chelonian ecology concerning its natural history and ecology. -

Herpetological Journal SHORT NOTE

Volume 28 (April 2018), 93-95 SHORT NOTE Herpetological Journal Published by the British Intersexuality in Helicops infrataeniatus Jan, 1865 Herpetological Society (Dipsadidae: Hydropsini) Ruth A. Regnet1, Fernando M. Quintela1, Wolfgang Böhme2 & Daniel Loebmann1 1Universidade Federal do Rio Grande, Instituto de Ciências Biológicas, Laboratório de Vertebrados. Av. Itália km 8, CEP: 96203-900, Vila Carreiros, Rio Grande, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil 2Zoologisches Forschungsmuseum A. Koenig, Adenauerallee 160, D-53113 Bonn, Germany Herein, we describe the first case of intersexuality in the are viviparous, and interestingly, H. angulatus exhibits Hydropsini tribe. After examination of 720 specimens both reproductive modes (Rossman, 1984; Aguiar & Di- of Helicops infrataeniatus Jan, 1865, we discovered Bernardo, 2005; Braz et al., 2016). Helicops infrataeniatus one individual that presented feminine and masculine has a wide distribution that encompasses south- reproductive features. The specimen was 619 mm long, southeastern Brazil, southern Paraguay, North-eastern with seven follicles in secondary stage, of different shapes Argentina and Uruguay (Deiques & Cechin, 1991; Giraudo, and sizes, and a hemipenis with 13.32 and 13.57 mm in 2001; Carreira & Maneyro, 2013). At the coastal zone of length. The general shape of this organ is similar to that southernmost Brazil, H. infrataeniatus is among the most observed in males, although it is smaller and does not abundant species in many types of limnic and estuarine present conspicuous spines along its body. Deformities environments (Quintela & Loebmann, 2009; Regnet found in feminine and masculine structures suggest that et al., 2017). In October 2015 at the Laranjal beach, this specimen might not be reproductively functional. municipality of Pelotas, state of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil (31°46’S, 52°13’W), a remarkable aggregation of reptiles Key words: Follicles, hemipenis, hermaphroditism, water and caecilians occurred after a flood event associated to snake. -

Download Vol. 33, No. 3

1. , F -6 ~.: 1/JJ/im--3'PT* JL* iLLLZW 1- : s . &, , I ' 4% Or *-* 0 4 Z 0 8 of the FLORIDA STATE MUSEUM Biological Sciences Volume 33 1988 Number 3 REPRODUCTIVE STRATEGIES OF SYMPATRIC FRESHWATER EMYDID TURTLES IN NORTHERN PENINSULAR FLORIDA Dale R. Jackson 3-C p . i ... h¢ 4 f .6/ I Se 4 .¢,$ I - - 64». 4 +Ay. 9.H>« UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA GAINESVILLE Numbers of the BULLETIN OF TIIE FLORIDA STATE MUSEUM, BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES, are published at irregular intervals. Volumes contain about 300 pages and,are not necessarily completed in any one calendar year. S. DAVID WEBB, Editor OLIVER L. AUSTIN, JR., Editor Bile,ints RHODA J. BRYANT, Managing Editor Communications concerning purchase or exchange of the publications and all manuscripts should be addressed to: Managing Editor, Bulletin; Florida State Museum; University of Florida; Gainesville FL 32611; U.S.A. This public document was promulgated at an annual cost of $2003.53 or $2.000 per copy. It makes available to libraries, scholars, and all interested persons the results of researches in the natural sciences, emphasizing the circum- Caribbean region. ISSN: 0071-6154 CODEN: BFSBAS Publication date: 8/27 Price: $2.00 REPRODUCTIVE STRATEGIES OF SYMPATRIC FRESHWATER EMYDID TURTLES IN NORTHERN PENINSULAR FLORIDA Dale R. Jackson Frontispiece. Alligator nest on Payne's Prairie, Alachua County, Florida, opened to expose seven clutches of Psmdenzys nelsoni eggs and one clutch of Trioi,br ferox eggs (far lower right) surrounding the central clutch of alligator eggs. Most of the alligator eggs had been destroyed earlier by raccoons. REPRODUCTIVE STRATEGIES OF SYMPATRIC FRESHWATER EMYDID TURTLES IN NORTHERN PENINSULAR FLORIDA Dale R. -

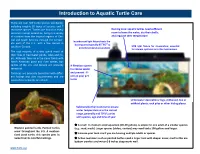

Introduction to Aquatic Turtle Care

Mississippi Map Turtle Introduction to Aquatic Turtle Care There are over 300 turtle species worldwide, including roughly 60 types of tortoise and 7 sea turtle species. Turtles are found on every Basking area: aquatic turtles need sufficient continent except Antarctica, living in a variety room to leave the water, dry their shells, of climates from the tropical regions of Cen- and regulate their temperature. tral and South America through the temper- Incandescent light fixture heats the ate parts of the U.S., with a few species in o- o) basking area (typically 85 95 to UVB light fixture for illumination; essential southern Canada. provide temperature gradient for vitamin synthesis in turtles held indoors The vast majority of turtles spend much of their lives in freshwater ponds, lakes and riv- ers. Although they are in the same family with North American pond and river turtles, box turtles of the U.S. and Mexico are primarily A filtration system terrestrial. to remove waste Tortoises are primarily terrestrial with differ- and prevent ill- ent habitat and diet requirements and are ness in your pet covered in a separate care sheet. turtle Underwater decorations: logs, driftwood, live or artificial plants, rock piles or other hiding places. Submersible thermometer to ensure water temperature is in the correct range, generally mid 70osF; varies with species, age and time of year A small to medium-sized aquarium (20-29 gallons) is ample for one adult of a smaller species Western painted turtle. Painted turtles (e.g., mud, musk). Larger species (sliders, cooters) may need tanks 100 gallons and larger. -

The Case of Deirocheline Turtles

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/556670; this version posted February 21, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 1 Body coloration and mechanisms of colour production in Archelosauria: 2 The case of deirocheline turtles 3 Jindřich Brejcha1,2*†, José Vicente Bataller3, Zuzana Bosáková4, Jan Geryk5, 4 Martina Havlíková4, Karel Kleisner1, Petr Maršík6, Enrique Font7 5 1 Department of Philosophy and History of Science, Faculty of Science, Charles University, Viničná 7, Prague 6 2, 128 00, Czech Republic 7 2 Department of Zoology, Natural History Museum, National Museum, Václavské nám. 68, Prague 1, 110 00, 8 Czech Republic 9 3 Centro de Conservación de Especies Dulceacuícolas de la Comunidad Valenciana. VAERSA-Generalitat 10 Valenciana, El Palmar, València, 46012, Spain. 11 4 Department of Analytical Chemistry, Faculty of Science, Charles University, Hlavova 8, Prague 2, 128 43, 12 Czech Republic 13 5 Department of Biology and Medical Genetics, 2nd Faculty of Medicine, Charles University and University 14 Hospital Motol, V Úvalu 84, 150 06 Prague, Czech Republic 15 6 Department of Food Science, Faculty of Agrobiology, Food, and Natural Resources, Czech University of Life 16 Sciences, Kamýcká 129, Prague 6, 165 00, Czech Republic 17 7 Ethology Lab, Cavanilles Institute of Biodiversity and Evolutionary Biology, University of Valencia, C/ 18 Catedrátic José Beltrán Martinez 2, Paterna, València, 46980, Spain 19 Keywords: Chelonia, Trachemys scripta, Pseudemys concinna, nanostructure, pigments, chromatophores 20 21 Abstract 22 Animal body coloration is a complex trait resulting from the interplay of multiple colour-producing mechanisms. -

Year of the Turtle News No

Year of the Turtle News No. 1 January 2011 Basking in the Wonder of Turtles www.YearoftheTurtle.org Welcome to 2011, the Wood Turtle, J.D. Kleopfer Bog Turtle, J.D. Willson Year of the Turtle! Turtle conservation groups in partnership with PARC have designated 2011 as the Year of the Turtle. The Chinese calendar declares 2011 as the Year of the Rabbit, and we are all familiar with the story of the “Tortoise and the Hare”. Today, there Raising Awareness for Turtle State of the Turtle Conservation is in fact a race in progress—a race to extinction, and turtles, unfortunately, Trouble for Turtles Our Natural Heritage of Turtles are emerging in the lead, ahead The fossil record shows us that While turtles (which include of birds, mammals, and even turtles, as we know them today, have tortoises) occur in fresh water, salt amphibians. The majority of turtle been on our planet since the Triassic water, and on land, their shells make threats are human-caused, which also Period, over 220 million years ago. them some of the most distinctive means that we can work together to Although they have persisted through animals on Earth. Turtles are so address turtle conservation issues many tumultuous periods of Earth’s unique that some scientists argue that and to help ensure the continued history, from glaciations to continental they should be in their own Class of survival of these important animals. shifts, they are now at the top of the vertebrates, Chelonia, separate from Throughout the year we will be raising list of species disappearing from the reptiles (such as lizards and snakes) awareness of the issues surrounding planet: 47.6% of turtle species are and other four-legged creatures. -

AN INTRODUCTION to Texas Turtles

TEXAS PARKS AND WILDLIFE AN INTRODUCTION TO Texas Turtles Mark Klym An Introduction to Texas Turtles Turtle, tortoise or terrapin? Many people get confused by these terms, often using them interchangeably. Texas has a single species of tortoise, the Texas tortoise (Gopherus berlanderi) and a single species of terrapin, the diamondback terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin). All of the remaining 28 species of the order Testudines found in Texas are called “turtles,” although some like the box turtles (Terrapene spp.) are highly terrestrial others are found only in marine (saltwater) settings. In some countries such as Great Britain or Australia, these terms are very specific and relate to the habit or habitat of the animal; in North America they are denoted using these definitions. Turtle: an aquatic or semi-aquatic animal with webbed feet. Tortoise: a terrestrial animal with clubbed feet, domed shell and generally inhabiting warmer regions. Whatever we call them, these animals are a unique tie to a period of earth’s history all but lost in the living world. Turtles are some of the oldest reptilian species on the earth, virtually unchanged in 200 million years or more! These slow-moving, tooth less, egg-laying creatures date back to the dinosaurs and still retain traits they used An Introduction to Texas Turtles | 1 to survive then. Although many turtles spend most of their lives in water, they are air-breathing animals and must come to the surface to breathe. If they spend all this time in water, why do we see them on logs, rocks and the shoreline so often? Unlike birds and mammals, turtles are ectothermic, or cold- blooded, meaning they rely on the temperature around them to regulate their body temperature. -

Species Results from Database Search

Species Results From Database Search Category Reptiles Common Name Alabama Map Turtle Scientific Name Graptemys pulchra LCC Global Trust N No. of States 1 Habitat_Feature Category Reptiles Common Name Black Kingsnake Scientific Name Lampropeltis getula nigra LCC Global Trust N No. of States 2 Habitat_Feature Category Reptiles Common Name Black Racer Scientific Name Coluber constrictor constrictor LCC Global Trust N No. of States 1 Habitat_Feature Category Reptiles Common Name Black Rat Snake Scientific Name Elaphe obsoleta LCC Global Trust N No. of States 2 Habitat_Feature Category Reptiles Common Name Bog turtle Scientific Name Clemmys (Glyptemys) muhlen LCC Global Trust Y No. of States 4 Habitat_Feature Monday, January 28, 2013 Page 1 of 14 Category Reptiles Common Name Broadhead Skink Scientific Name Eumeces laticeps LCC Global Trust N No. of States 5 Habitat_Feature Category Reptiles Common Name Coal Skink Scientific Name Eumeces anthracinus LCC Global Trust Y No. of States 8 Habitat_Feature Category Reptiles Common Name Common Five-lined Skink Scientific Name Eumeces fasciatus LCC Global Trust N No. of States 2 Habitat_Feature Category Reptiles Common Name Common Map Turtle Scientific Name Graptemys geographica LCC Global Trust N No. of States 6 Habitat_Feature Category Reptiles Common Name Common Musk Turtle Scientific Name Sternotherus odoratus LCC Global Trust N No. of States 2 Habitat_Feature Monday, January 28, 2013 Page 2 of 14 Category Reptiles Common Name Common Ribbonsnake Scientific Name Thamnophis sauritus sauritus LCC Global Trust N No. of States 6 Habitat_Feature Category Reptiles Common Name Common Snapping Turtle Scientific Name Chelydra serpentina LCC Global Trust N No. of States 2 Habitat_Feature Category Reptiles Common Name Corn snake Scientific Name Elaphe guttata guttata LCC Global Trust N No. -

Reptiles of Greatest Conservation Need

APPENDIX K. REPTILES OF GREATEST CONSERVATION NEED Taxa Common Name Scientific Name Tier Opportunity Ranking Reptiles Bog turtle Clemmys muhlenbergii I a Reptiles Canebrake rattlesnake Crotalus horridus (canebrake) II a Reptiles Common ribbonsnake Thamnophis sauritus sauritus IV a Reptiles Common snapping Turtle Chelydra serpentina IV b Reptiles Cumberland slider Trachemys scripta troostii III c Reptiles Eastern black kingsnake Lampropeltis nigra III c Reptiles Eastern box turtle Terrapene carolina carolina III a Reptiles Eastern chicken turtle Deirochelys reticularia I a reticularia Reptiles Eastern glass lizard Ophisaurus ventralis II a Reptiles Eastern hog-nosed snake Heterodon platirhinos IV c Reptiles Eastern slender glass Ophisaurus attenuatus IV a lizard longicaudus Reptiles Glossy crayfish snake Regina rigida rigida III c Reptiles Green Sea Turtle Chelonia mydas I b Reptiles Kemp's ridley sea turtle Lepidochelys kempii I a Reptiles Leatherback Sea Turtle Dermochelys coriacea I c Reptiles Loggerhead sea turtle Caretta caretta I a Reptiles Mountain earthsnake Virginia valeriae pulchra II c Reptiles Mudsnake Farancia abacura abacura IV a Reptiles Northern diamondback Malaclemys terrapin terrapin II a terrapin Reptiles Northern map turtle Graptemys geographica IV a Virginia Wildlife Action Plan 2015 APPENDIX K. REPTILES OF GREATEST CONSERVATION NEED Reptiles Northern pinesnake Pituophis melanoleucus I a melanoleucus Reptiles Queen snake Regina septemvittata IV a Reptiles Rainbow snake Farancia erytrogramma IV a erytrogramma Reptiles -

EMYDIDAE P Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles

REPTILIA: TESTUDINES: EMYDIDAE P Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles. Pseudemysj7oridana: Baur, 1893:223 (part). Pseudemys texana: Brimley, 1907:77 (part). Seidel, M.E. and M.J. Dreslik. 1996. Pseudemys concinna. Chrysemysfloridana: Di tmars, 1907:37 (part). Chrysemys texana: Hurter and Strecker, 1909:21 (part). Pseudemys concinna (LeConte) Pseudemys vioscana Brimley, 1928:66. Type-locality, "Lake River Cooter Des Allemands [St. John the Baptist Parrish], La." Holo- type, National Museum of Natural History (USNM) 79632, Testudo concinna Le Conte, 1830: 106. Type-locality, "... rivers dry adult male collected April 1927 by Percy Viosca Jr. of Georgia and Carolina, where the beds are rocky," not (examined by authors). "below Augusta on the Savannah, or Columbia on the Pseudemys elonae Brimley, 1928:67. Type-locality, "... pond Congaree," restricted to "vicinity of Columbia, South Caro- in Guilford County, North Carolina, not far from Elon lina" by Schmidt (1953: 101). Holotype, undesignated, see College, in the Cape Fear drainage ..." Holotype, USNM Comment. 79631, dry adult male collected October 1927 by D.W. Tesrudofloridana Le Conte, 1830: 100 (part). Type-locality, "... Rumbold and F.J. Hall (examined by authors). St. John's river of East Florida ..." Holotype, undesignated, see Comment. Emys (Tesrudo) concinna: Bonaparte, 1831 :355. Terrapene concinna: Bonaparte, 183 1 :370. Emys annulifera Gray, 183 1:32. Qpe-locality, not given, des- ignated as "Columbia [Richland County], South Carolina" by Schmidt (1953: 101). Holotype, undesignated, but Boulenger (1889:84) listed the probable type as a young preserved specimen in the British Museum of Natural His- tory (BMNH) from "North America." Clemmys concinna: Fitzinger, 1835: 124. -

The Global Distribution of Tetrapods Reveals a Need for Targeted Reptile

1 The global distribution of tetrapods reveals a need for targeted reptile 2 conservation 3 4 Uri Roll#1,2, Anat Feldman#3, Maria Novosolov#3, Allen Allison4, Aaron M. Bauer5, Rodolphe 5 Bernard6, Monika Böhm7, Fernando Castro-Herrera8, Laurent Chirio9, Ben Collen10, Guarino R. 6 Colli11, Lital Dabool12 Indraneil Das13, Tiffany M. Doan14, Lee L. Grismer15, Marinus 7 Hoogmoed16, Yuval Itescu3, Fred Kraus17, Matthew LeBreton18, Amir Lewin3, Marcio Martins19, 8 Erez Maza3, Danny Meirte20, Zoltán T. Nagy21, Cristiano de C. Nogueira19, Olivier S.G. 9 Pauwels22, Daniel Pincheira-Donoso23, Gary Powney24, Roberto Sindaco25, Oliver Tallowin3, 10 Omar Torres-Carvajal26, Jean-François Trape27, Enav Vidan3, Peter Uetz28, Philipp Wagner5,29, 11 Yuezhao Wang30, C David L Orme6, Richard Grenyer✝1 and Shai Meiri✝*3 12 13 # Contributed equally to the paper 14 ✝ Contributed equally to the paper 15 * Corresponding author 16 17 Affiliations: 18 1 School of Geography and the Environment, University of Oxford, Oxford, OX13QY, UK. 19 2 Mitrani Department of Desert Ecology, The Jacob Blaustein Institutes for Desert Research, 20 Ben-Gurion University, Midreshet Ben-Gurion 8499000, Israel. (Current address) 21 3 Department of Zoology, Tel-Aviv University, Tel-Aviv 6997801, Israel. 22 4 Hawaii Biological Survey, 4 Bishop Museum, Honolulu, HI 96817, USA. 23 5 Department of Biology, Villanova University, Villanova, PA 19085, USA. 24 6 Department of Life Sciences, Imperial College London, Silwood Park Campus Silwood Park, 25 Ascot, Berkshire, SL5 7PY, UK 26 7 Institute of Zoology, Zoological Society of London, London NW1 4RY, UK. 27 8 School of Basic Sciences, Physiology Sciences Department, Universidad del Valle, Colombia.