The Enigma of Toyota's Competitive Advantage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

It's the Toyota Payoff Line and Also What the Brand Lives

THE MARKET than ever before. When designing this Corolla, sales, Toyota has been the market leader for 27 Lead the Way: It’s the Toyota payoff line and also Chief Engineer Soichiro Okudaira says Toyota years, with record 2006 sales of 150,000 units, what the brand lives up to with its eighteen product needed to create a car that continued to offer the with the Corolla being the most popular vehicle, offerings at the right price, the right quality and at DNA of Corolla, but to incorporate something making record sales every month. the right time. With a turnover in its last financial new. This Corolla closes the gap between its C- Toyota is currently the market leader in year of R30 billion, millions of people around the segment class and the higher D-segment, creating passenger and commercial vehicle sales, with world also see Toyota leading the way. a new class in its category across the board. Corolla the top selling passenger vehicle and Among its wide and popular range of It is based on the “five metre” design Yaris the top imported passenger vehicle. passenger and commercial vehicles, the Toyota philosophy: Within the first five metres and five Hilux is the top commercial vehicle, and trump card is the Corolla, which enjoys the status minutes that you see it, touch it, feel it and drive was the market leader in 2006 with 2,361 of being the best selling car worldwide. it, you can identify the difference in quality and sales. Quantum is the top imported commercial The Toyota Corolla is currently produced in 16 comfort. -

Defendants and Auto Parts List

Defendants and Parts List PARTS DEFENDANTS 1. Wire Harness American Furukawa, Inc. Asti Corporation Chiyoda Manufacturing Corporation Chiyoda USA Corporation Denso Corporation Denso International America Inc. Fujikura America, Inc. Fujikura Automotive America, LLC Fujikura Ltd. Furukawa Electric Co., Ltd. G.S. Electech, Inc. G.S. Wiring Systems Inc. G.S.W. Manufacturing Inc. K&S Wiring Systems, Inc. Kyungshin-Lear Sales And Engineering LLC Lear Corp. Leoni Wiring Systems, Inc. Leonische Holding, Inc. Mitsubishi Electric Automotive America, Inc. Mitsubishi Electric Corporation Mitsubishi Electric Us Holdings, Inc. Sumitomo Electric Industries, Ltd. Sumitomo Electric Wintec America, Inc. Sumitomo Electric Wiring Systems, Inc. Sumitomo Wiring Systems (U.S.A.) Inc. Sumitomo Wiring Systems, Ltd. S-Y Systems Technologies Europe GmbH Tokai Rika Co., Ltd. Tram, Inc. D/B/A Tokai Rika U.S.A. Inc. Yazaki Corp. Yazaki North America Inc. 2. Instrument Panel Clusters Continental Automotive Electronics LLC Continental Automotive Korea Ltd. Continental Automotive Systems, Inc. Denso Corp. Denso International America, Inc. New Sabina Industries, Inc. Nippon Seiki Co., Ltd. Ns International, Ltd. Yazaki Corporation Yazaki North America, Inc. Defendants and Parts List 3. Fuel Senders Denso Corporation Denso International America, Inc. Yazaki Corporation Yazaki North America, Inc. 4. Heater Control Panels Alps Automotive Inc. Alps Electric (North America), Inc. Alps Electric Co., Ltd Denso Corporation Denso International America, Inc. K&S Wiring Systems, Inc. Sumitomo Electric Industries, Ltd. Sumitomo Electric Wintec America, Inc. Sumitomo Electric Wiring Systems, Inc. Sumitomo Wiring Systems (U.S.A.) Inc. Sumitomo Wiring Systems, Ltd. Tokai Rika Co., Ltd. Tram, Inc. 5. Bearings Ab SKF JTEKT Corporation Koyo Corporation Of U.S.A. -

How Progressive Companies Create Long-Term Value and Competitive Advantage

How Progressive Companies Create Long-Term Value and Competitive Advantage Through their talent development strategy Through Their Talent Development Strategy How can I have a talent development strategy when I can’t find the talent? Topics Covered 1. Why employers can’t fill their open positions 2. Who’s available 3. How to create a talent development strategy – and integrate into business strategy a) Job design b) Sources of talent c) Operations d) Benchmarking 4. What this means for your business and your community 5. Call to Action 6. How to use this information 1 Why employers can’t fill their open positions Why You Can’t Fill Your Open Positions Skills Gap YES, 90% of jobs require some education or training after high school, but only 50% of us have that Awareness and Parental Influence YES, parents are biased against some sectors or non- bachelor degree programs Why You Can’t Fill Your Open Positions There are barriers to overcome Transportation to school and/or work Transit study/regional indicators report – only 59% of regional jobs are reachable by public transit Access to affordable, quality child care that meshes with job and/or school schedules Quality child care is more expensive than college tuition Home based care vs. center based care is preferred for evenings/overnights i.e. 2nd and 3rd shift Intimate Partner Violence On average, 30% (some sites 50%+) of job seekers (81% female/19% male) have some experience with intimate partner intimidation or violence 177 children in the homes of those reporting issues Why You Can’t Fill Your Open Positions They can’t afford to go back to school …or to take that job. -

World Business and the Multilateral Trading System

International Chamber of Commerce The world business organization Policy statement Commission on Trade and Investment Policy World business and the multilateral trading system ICC policy recommendations for the Cancún Ministerial Conference of the World Trade Organization (10-14 September 2003) Paris, 14 May 2003 International Chamber of Commerce 38, Cours Albert 1er, 75008 – Paris, France Telephone +33 1 49 53 28 28 Fax +33 1 49 53 28 59 Web site www.iccwbo.org E-mail [email protected] ICC policy statement WTO Cancún ministerial conference, 10-14 September 2003 World business and the multilateral trading system ICC policy recommendations for the Cancún Ministerial Conference of the World Trade Organization (10-14 September 2003) World business, as represented by ICC, believes strongly that the rules-based multilateral trading system built up through the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade/World Trade Organization (GATT/WTO) is one of the central pillars of international cooperation. It has contributed greatly to liberalizing world trade and improving market access, and is a major driving force for global economic growth, job creation, and wider consumer choice. ICC wishes to take this opportunity to convey key business messages and policy recommendations to trade ministers participating in the 5th WTO Ministerial Conference in September 2003 in Cancún (Mexico). Now that the war in Iraq is over, ICC urges WTO members to put their divisions behind them and commit themselves to renewed multilateral cooperation for the vital purposes of rebuilding business and consumer confidence and reinvigorating a weak global economy. It is in the urgent interest of all WTO member countries to work closely together to ensure the success of the Doha Development Agenda, launched at the 4th Ministerial Conference of the WTO in November 2001 at Doha (Qatar). -

Strategies for Competitive Advantage Cole Ehmke, M.S

WEMC FS#5-08 Strategies for Competitive Advantage Cole Ehmke, M.S. Extension Educator, Department of Agricultural and Applied Economics University of Wyoming Overview A competitive advantage is an advantage gained over competitors by offering customers greater value, either through lower prices or by providing additional benefits and service that justify similar, or possibly higher, prices. For growers and producers involved in niche marketing, finding and nurturing a competitive advantage can mean increased profit and a venture that is sustainable and successful over the long term. This fact sheet looks at what defines competitive advantage and discusses strategies to consider when building a competitive advantage, as well as ways to assess the competitive advantage of a venture. The Essence of Competitive Advantage To begin, it may be helpful to take a more in-depth look at what it means to have a competitive advantage: an edge over the competition. Essentially a competitive advantage answers the question, “Why should the customer purchase from this operation rather than the competition?” For some ventures, particularly those in markets where the products or services are less differentiated, answering this question can be difficult. A key point to understand is that a venture that has customers has customers for a reason. Successfully growing a business is often dependent upon a strong competitive edge that gradually builds a core of loyal customers, which can be expanded over time. Producers and suppliers familiar with farming and ranching may know that successful ventures in the agriculture industry have typically operated in a commoditized, price-driven market, where all parties produce essentially the same product. -

Building a Sustainable Competitive Advantage in Today's Knowledge

The Definitive Voice of the Career College Sector of Higher Education MOGHADAM November 2014 Building a Sustainable Competitive Advantage in Today’s Knowledge Economy Dr. Amir Moghadam President/CEO MaxKnowledge, Inc. It’s been widely accepted that we have entered a new era of knowledge-based economy where an organization’s effective utilization of intangible assets such as employee skills, abilities and innovation are key to building a competitive edge. What does this mean for career colleges? Career colleges, just like all organizations, must improve their adaptive capabilities to sustain long-term competitive advantage. Every institution must be effective at creating change; not just responding to it. Disruption has become a market norm and in higher education we’ve seen many examples including the emergence of massive open online courses (MOOCs), adaptive learning, competency-based programs, and of course regulatory changes to name only a few. Additionally, our market has experienced shifting student demographics as well as shifting attitudes about the purpose and ROI of higher education. How do career colleges create and embrace adaptability as a new competitive advantage? Institutional leaders must first recognize the potential their employees already possess. The collective, diverse cognitive power of an institution’s employees provides more opportunity for innovation than any other resource. Higher education institutions, more so than any other type of organization, should also understand that if people are the engine for innovation, knowledge provides the fuel that sets the engine in motion. Thus, an institution’s investment in its employees’ learning and professional development is an investment in building innovation capability necessary for sustainable competitive advantage. -

Newsletter | Your Update on What’S New from DENSO Aftermarket Sales

Newsletter | Your update on what’s new from DENSO Aftermarket Sales Issue number 46 | July/August 2015 Menu > Follow the links below! Inside this issue… > DENSO Lambda Sensors: manufacturing expertise > Out now! Latest Starters & Alternators > AEC became DENSO’s first engineering base for diesel range extension engine component applications outside Japan. > automotive Diamonds wins Loyalty Award > EE region: tradeshows round-up Opening of expanded Aachen > DENSO goes to Hollywood Engineering Centre heralds > May we introduce… new era of DENSO innovation Further demonstrating its European capability to design, said Masato (Max) Nakagawa, DENSO International Europe’s newly appointed develop, engineer and test parts and systems from President, CEO & CTO. “We are a vehicle-wide perspective, DENSO AUTOMOTIVE particularly proud of the all-new electronic Deutschland GmbH, a subsidiary of Japan-based DENSO laboratory. We can now offer in-house development of hardware and software Corporation, has expanded its Aachen Engineering for engine control units (ECU) used Centre (AEC). The opening ceremony took place at the on diesel and gasoline engines. newly expanded site in Wegberg, Germany on 2nd June. This laboratory also facilitates the accommodation of electric and hybrid The latest expansion means that AEC new European powertrain development technologies to European specifications. has the capacity to serve its European and shared their vision of further growth. The European region plays a global customers in the areas of powertrain, leadership role in the automotive industry electronics and electrical systems. Compared to the original engineering with respect to the creation of advanced At the opening ceremony, new AEC centre, which was opened in 2005, the technologies and innovative designs. -

Notice of Hearing in Canadian Auto Parts Class Actions- Long

NOTICE OF HEARING IN CANADIAN AUTO PARTS PRICE-FIXING CLASS ACTIONS If you bought or leased, directly or indirectly, a new or used Automotive Vehicle or certain automotive parts, since January 1998, you should read this notice carefully. It may affect your legal rights. A. WHAT IS A CLASS ACTION? A class action is a lawsuit filed by one person on behalf of a large group of people. B. WHAT ARE THESE CLASS ACTIONS ABOUT? Class actions have been started in Canada claiming that many companies participated in conspiracies to fix the prices of automotive parts sold in Canada and/or sold to manufacturers for installation in Automotive Vehicles1 sold in Canada. This notice is about class actions relating to the following automotive parts (the “Relevant Parts”): Part Description2 Class Period Air Conditioning Air Conditioning Systems are systems that cool the January 1, 2001 to Systems interior environment of an Automotive Vehicle and are December 10, 2019 part of an Automotive Vehicle’s thermal system. An Air Conditioning System may include, to the extent included in the relevant request for quotation, compressors, condensers, HVAC units (blower motors, actuators, flaps, evaporators, heater cores, and filters embedded in a plastic housing), control panels, sensors, and associated hoses and pipes. Air Flow Meters Air Flow Meters, otherwise known as a mass air flow January 1, 2000 to sensors, measure the volume of air flowing into March 20, 2017 combustion engines in Automotive Vehicles, that is, how much air is flowing through a valve or passageway. The Air Flow Meter provides information to the Automotive Vehicle’s electronic control unit in order to ensure that the proper ratio of fuel to air is being injected into the engine. -

Renesas Electronics Announces Share Issue Through Third-Party Allotment, and Change in Major Shareholders, Largest Shareholder W

Renesas Electronics Announces Share Issue through Third-Party Allotment, and Change in Major Shareholders, Largest Shareholder who is a Major Shareholder, Parent Company and Other Related Companies TOKYO, Japan, December 10, 2012 – Renesas Electronics Corporation (TSE: 6723, hereafter “Renesas” or “the Company”), a premier supplier of advanced semiconductor solutions, at a meeting of the board of directors held today, resolved to issue shares through Third-Party Allotment to The Innovation Network Corporation of Japan (“INCJ”), Toyota Motor Corporation, Nissan Motor Co., Ltd., Keihin Corporation, Denso Corporation, Canon Inc., Nikon Corporation, Panasonic Corporation and Yaskawa Electric Corporation, and (hereafter the “scheduled subscribers”). In implementing the Third-Party Allotment, one of the scheduled subscribers, INCJ, is required to file for regulatory approval in relation to business mergers with competition authorities in various countries, and the payment pertaining to the Allotment of Third Party Shares is subject to approval from all the applicable regulatory authorities. Furthermore, implementation of the Third-Party Allotment will result in changes to major shareholders, the largest shareholder who is a major shareholder, the parent company and other related companies, as outlined herein. I. Outline of the Third-Party Allotment 1. Outline of the offering February 23, 2013 through September 30, 2013 (Note 1) The above schedule takes into account the time required by the competition authorities of each country where INCJ, one of the (1) Issue period scheduled subscribers, files application, to review the Third-Party Allotment. Payment for the following total of shares is to be made promptly by the scheduled subscribers after approval from all applicable antitrust authorities, etc. -

Newsletter | Your Update on What’S New from DENSO Aftermarket Sales

Newsletter | Your update on what’s new from DENSO Aftermarket Sales Issue number 42 | March 2015 Menu > Follow the links below! Inside this issue… > Auto Professioneel & Schadeherstel Tradeshow, Netherlands > Spotlight on Spark Plugs > 2014 FIA WEC Toyota Racing win > Third quarter financial results > May we introduce – Mark Robertson > Toyota TS030 Hybrid Le Mans racing car on stand, featuring a rear hybrid motor system specifically developed by DENSO. Gorinchem tradeshow a sparkling success DENSO exhibited at the Auto Professioneel answer questions on all DENSO products continue strengthening interest in the & Schadeherstel Tradeshow which took available to retailers and garages. DENSO brand in the Netherlands,” place in Gorinchem, The Netherlands explained Dominic. on February 3rd – 5th. The three day Another big draw on the stand was the event attracted around 16,000 visitors, DENSO sponsored Toyota TS030 Hybrid The next Auto Professioneel & and featured 250 exhibitors from the Le Mans racing car, featuring a rear Schadeherstel Tradeshow will take automotive industry. hybrid motor system specifically place in early 2016. developed by DENSO. DENSO took the opportunity to showcase a selection of products and parts from Stand visitors also had the opportunity its world-leading aftermarket programme to register with Automotive Diamonds, on three display areas which have been the popular, web-based customer loyalty tailor-made for exhibitions. Interest from scheme enabling garages and installers workshop and wholesaler visitors to the to maximise the benefits and reap the stand was also very high, with particular rewards of purchasing products from emphasis on A/C Compressors thanks to a DENSO and its programme partners. -

Lighter Battery Key to Success of Hybrids

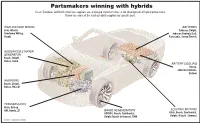

◆ JULY 10, 2006 AUTOMOTIVE NEWS EUROPE 21 ◆ Lighter battery key to success of hybrids Lithium-ion offers weight, cost benefits Partsmakers winning with hybrids over nickel metal Asian, European and North American suppliers are all playing important roles in the development of hybrid powertrains. Below are some of the leading hybrid suppliers by specific part. RICHARD TRUETT AUTOMOTIVE NEWS EUROPE HIGH-VOLTAGE WIRING BATTERIES Batteries may be the key to the Lear, Hitachi, Cobasys, Delphi, future of gasoline-electric hybrids. Sumitomo Wiring, Johnson Controls/Saft, If hybrids are ever going to earn Yazaki Panasonic, Sanyo Electric automakers a profit, the cost of the batteries must decrease and the life of the battery pack increase. The number of battery suppliers also must expand so that batteries are INTEGRATED STARTER just another commodity, like wind- GENERATOR shield wipers and headlights. Bosch, Delphi, Lithium ion – the same type of Denso, Valeo powerful, compact battery in your BATTERY COOLING mobile phone and digital camera – Denso, could be the wonder battery that Johnson Controls, delivers all that and more. Visteon Virtually all of today’s hybrids use nickel-metal hydride batteries. Nickel metal has proved to be reli- INVERTERS able, but the battery packs are Bosch, Delphi, heavy, and the materials inside are Denso, Hitachi expensive compared with those in lithium-ion packs. Expensive replacement Also, most experts think that TRANSMISSIONS hybrid cars, such as the Toyota Aisin, Getrag, Prius, will need a replacement bat- GM, Honda, ZF BRAKE REGENERATION ELECTRIC MOTORS tery pack after eight years or ADVICS, Bosch, Continental, Aisin, Bosch, Continental, 100,000 miles. -

Toyota Boshoku Report 2012 Toyota Boshoku Welcomed Ms

TOYOTA BOSHOKU REPORT 2012 2011.4.1—2012.3.31 Looking into the future, we will create tomorrow’s automobile interior space that will inspire our customers the world over. Manufacturing To offer products that appeal to people of all countries throughout the world and that are recognised globally for high quality, the Toyota Boshoku group works together with suppliers and undertakes manufacturing from the perspective of customers. Development Capabilities As an interior system supplier, Toyota Boshoku is taking on the challenge of total technological innovation for interior components, filtration and powertrain components and textiles and exterior components from the unique perspective of interior space without being constrained by the current shape of vehicles. Environmental Technologies The Toyota Boshoku group is working in concert to undertake a variety of global initiatives to address environmental issues, which are now being demanded of companies. These initiatives include formulating the 2015 Environmental Action Plan and creating technologies and products and building production processes that contribute to the environment. Global Development To achieve further growth as a truly global company, the Global Mainstay Hub and Regional Management & Collaboration Hubs will collaborate closely and promote efficient management while carrying out strategic business that accurately ascertains market trends in each region. Human Resources Development To expand business globally, we will develop personnel with high-level skills and techniques and who are adept at manufacturing. At the same time, we will promote programmes in different countries all over the world aimed at developing trainees into advanced trainers. Global Network The Toyota Boshoku group divides its bases into five regions of the world, specifically North & South America, Asia & Oceania, China, Europe & Africa and Japan.