A. Cocoa Sector (Province Equateur and Nord Kivu)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Of the United Nations Mission in the DRC / MONUC – MONUSCO

Assessing the of the United Nations Mission in the DRC / MONUC – MONUSCO REPORT 3/2019 Publisher: Norwegian Institute of International Affairs Copyright: © Norwegian Institute of International Affairs 2019 ISBN: 978-82-7002-346-2 Any views expressed in this publication are those of the author. Tey should not be interpreted as reflecting the views of the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs. Te text may not be re-published in part or in full without the permission of NUPI and the authors. Visiting address: C.J. Hambros plass 2d Address: P.O. Box 8159 Dep. NO-0033 Oslo, Norway Internet: effectivepeaceops.net | www.nupi.no E-mail: [email protected] Fax: [+ 47] 22 99 40 50 Tel: [+ 47] 22 99 40 00 Assessing the Efectiveness of the UN Missions in the DRC (MONUC-MONUSCO) Lead Author Dr Alexandra Novosseloff, International Peace Institute (IPI), New York and Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI), Oslo Co-authors Dr Adriana Erthal Abdenur, Igarapé Institute, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Prof. Tomas Mandrup, Stellenbosch University, South Africa, and Royal Danish Defence College, Copenhagen Aaron Pangburn, Social Science Research Council (SSRC), New York Data Contributors Ryan Rappa and Paul von Chamier, Center on International Cooperation (CIC), New York University, New York EPON Series Editor Dr Cedric de Coning, NUPI External Reference Group Dr Tatiana Carayannis, SSRC, New York Lisa Sharland, Australian Strategic Policy Institute, Canberra Dr Charles Hunt, Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT) University, Australia Adam Day, Centre for Policy Research, UN University, New York Cover photo: UN Photo/Sylvain Liechti UN Photo/ Abel Kavanagh Contents Acknowledgements 5 Acronyms 7 Executive Summary 13 Te effectiveness of the UN Missions in the DRC across eight critical dimensions 14 Strategic and Operational Impact of the UN Missions in the DRC 18 Constraints and Challenges of the UN Missions in the DRC 18 Current Dilemmas 19 Introduction 21 Section 1. -

Download File

UNICEF DRC | COVID-19 Situation Report COVID-19 Situation Report #9 29 May-10 June 2020 /Desjardins COVID-19 overview Highlights (as of 10 June 2020) 25702 • 4.4 million children have access to distance learning UNI3 confirmed thanks to partnerships with 268 radio stations and 20 TV 4,480 cases channels © UNICEF/ UNICEF’s response deaths • More than 19 million people reached with key messages 96 on how to prevent COVID-19 people 565 recovered • 29,870 calls managed by the COVID-19 Hotline • 4,338 people (including 811 children) affected by COVID-19 cases under 388 investigation and 837 frontline workers provided with psychosocial support • More than 200,000 community masks distributed 2.3% Fatality Rate 392 new samples tested UNICEF’s COVID-19 Response Kinshasa recorded 88.8% (3,980) of all confirmed cases. Other affected provinces including # of cases are: # of people reached on COVID-19 through North Kivu (35) South Kivu (89) messaging on prevention and access to 48% Ituri (2) Kongo Central (221) Haut RCCE* services Katanga (38) Kwilu (2) Kwango (1) # of people reached with critical WASH Haut Lomami (1) Tshopo (1) supplies (including hygiene items) and services 78% IPC** Equateur (1) # of children who are victims of violence, including GBV, abuse, neglect or living outside 88% DRC COVID-19 Response PSS*** of a family setting that are identified and… Funding Status # of children and women receiving essential healthcare services in UNICEF supported 34% Health facilities Funds # of caregivers of children (0-23 months) available* DRC COVID-19 reached with messages on breadstfeeding in 15% 30% Funding the context of COVID-19 requirements* : Nutrition $ 58,036,209 # of children supported with distance/home- 29% based learning Funding Education Gap 70% 0% 20% 40% 60% 80% 100% *Funds available include 9 million USD * Risk Communication and Community Engagement UNICEF regular ressources allocated by ** Infection Prevention and Control the office for first response needs. -

Democratic Republic of the Congo of the Congo Democratic Republic

Democratic Republic of the Congo of the Congo Democratic Republic Main objectives Impact • UNHCR provided international protection to some In 2005, UNHCR aimed to strengthen the protection 204,300 refugees in the DRC of whom some 15,200 framework through national capacity building, registra- received humanitarian assistance. tion, and the prevention of and response to sexual and • Some of the 22,400 refugees hosted by the DRC gender-based violence; facilitate the voluntary repatria- were repatriated to their home countries (Angola, tion of Angolan, Burundian, Rwandan, Ugandan and Rwanda and Burundi). Sudanese refugees; provide basic assistance to and • Some 38,900 DRC Congolese refugees returned to locally integrate refugee groups that opt to remain in the the DRC, including 14,500 under UNHCR auspices. Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC); prepare and UNHCR monitored the situation of at least 32,000 of organize the return and reintegration of DRC Congolese these returnees. refugees into their areas of origin; and support initiatives • With the help of the local authorities, UNHCR con- for demobilization, disarmament, repatriation, reintegra- ducted verification exercises in several refugee tion and resettlement (DDRRR) and the Multi-Country locations, which allowed UNHCR to revise its esti- Demobilization and Reintegration Programme (MDRP) mates of the beneficiary population. in cooperation with the UN peacekeeping mission, • UNHCR continued to assist the National Commission UNDP and the World Bank. for Refugees (CNR) in maintaining its advocacy role, urging local authorities to respect refugee rights. UNHCR Global Report 2005 123 Working environment Recurrent security threats in some regions have put another strain on this situation. -

Democratic Republic of the Congo – Ebola Outbreaks SEPTEMBER 30, 2020

Fact Sheet #10 Fiscal Year (FY) 2020 Democratic Republic of the Congo – Ebola Outbreaks SEPTEMBER 30, 2020 SITUATION AT A GLANCE 128 53 13 3,470 2,287 Total Confirmed and Total EVD-Related Total EVD-Affected Total Confirmed and Total EVD-Related Probable EVD Cases in Deaths in Équateur Health Zones in Probable EVD Cases in Deaths in Eastern DRC Équateur Équateur Eastern DRC at End of at End of Outbreak Outbreak MoH – September 30, 2020 MoH – September 30, 2020 MoH – September 30, 2020 MoH – June 25, 2020 MoH – June 25, 2020 Health actors remain concerned about surveillance gaps in northwestern DRC’s Équateur Province. In recent weeks, several contacts of EVD patients have travelled undetected to neighboring RoC and the DRC’s Mai- Ndombe Province, heightening the risk of regional EVD spread. Logistics coordination in Equateur has significantly improved in recent weeks, with response actors establishing a Logistics Cluster in September. The 90-day enhanced surveillance period in eastern DRC ended on September 25. TOTAL USAID HUMANITARIAN FUNDING USAID/BHA1,2 $152,614,242 For the DRC Ebola Outbreaks Response in FY 2020 USAID/GH in $2,500,000 Neighboring Countries3 For complete funding breakdown with partners, see funding chart on page 6 Total $155,114,2424 1USAID’s Bureau for Humanitarian Assistance (USAID/BHA) 2 Total USAID/BHA funding includes non-food humanitarian assistance from the former Office of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance. 3 USAID’s Bureau for Global Health (USAID/GH) 4 Some of the USAID funding intended for Ebola virus disease (EVD)-related programs in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) is now supporting EVD response activities in Équateur. -

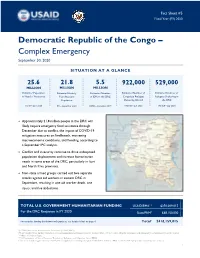

DRC Complex Emergency Fact Sheet #5 09.30.2020

Fact Sheet #5 Fiscal Year (FY) 2020 Democratic Republic of the Congo – Complex Emergency September 30, 2020 SITUATION AT A GLANCE 25.6 21.8 5.5 922,000 529,000 MILLION MILLION MILLION Estimated Population Estimated Acutely Estimated Number Estimated Number of Estimated Number of in Need of Assistance Congolese Refugees Refugees Sheltering in Food Insecure of IDPs in the DRC Population Sheltering Abroad the DRC OCHA – June 2020 UNHCR – July 2020 UNHCR – July 2020 IPC – September 2020 OCHA – December 2019 Approximately 21.8 million people in the DRC will likely require emergency food assistance through December due to conflict, the impact of COVID-19 mitigation measures on livelihoods, worsening macroeconomic conditions, and flooding, according to a September IPC analysis. Conflict and insecurity continue to drive widespread population displacement and increase humanitarian needs in some areas of the DRC, particularly in Ituri and North Kivu provinces. Non-state armed groups carried out two separate attacks against aid workers in eastern DRC in September, resulting in one aid worker death, one injury, and five abductions. TOTAL U.S. GOVERNMENT HUMANITARIAN FUNDING USAID/BHA1,2 $350,009,015 For the DRC Response in FY 2020 State/PRM3 $68,150,000 For complete funding breakdown with partners, see detailed chart on page 6 Total4 $418,159,015 1USAID’s Bureau for Humanitarian Assistance (USAID/BHA) 2 Total USAID/BHA funding includes non-food humanitarian assistance from the former Office of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance and emergency food assistance from the former Office of Food for Peace. 3 U.S. Department of State’s Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration (State/PRM) 4 This total includes approximately $23,833,699 in supplemental funding through USAID/BHA and State/PRM for COVID-19 preparedness and response activities. -

Review of the National Program for Onchocerciasis Control in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease Review Review of the National Program for Onchocerciasis Control in the Democratic Republic of the Congo Jean-Claude Makenga Bof 1,* , Fortunat Ntumba Tshitoka 2, Daniel Muteba 2, Paul Mansiangi 3 and Yves Coppieters 1 1 Ecole de Santé Publique, Université Libre de Bruxelles (ULB), Route de Lennik 808, 1070 Brussels, Belgium; [email protected] 2 Ministry of Health: Program of Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTD) for Preventive Chemotherapy (PC), Gombe, Kinshasa, DRC; [email protected] (F.N.T.); [email protected] (D.M.) 3 Faculty of Medicine, School of Public Health, University of Kinshasa (UNIKIN), Lemba, Kinshasa, DRC; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +32-493-93-96-35 Received: 3 May 2019; Accepted: 30 May 2019; Published: 13 June 2019 Abstract: Here, we review all data available at the Ministry of Public Health in order to describe the history of the National Program for Onchocerciasis Control (NPOC) in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). Discovered in 1903, the disease is endemic in all provinces. Ivermectin was introduced in 1987 as clinical treatment, then as mass treatment in 1989. Created in 1996, the NPOC is based on community-directed treatment with ivermectin (CDTI). In 1999, rapid epidemiological mapping for onchocerciasis surveys were launched to determine the mass treatment areas called “CDTI Projects”. CDTI started in 2001 and certain projects were stopped in 2005 following the occurrence of serious adverse events. Surveys coupled with rapid assessment procedures for loiasis and onchocerciasis rapid epidemiological assessment were launched to identify the areas of treatment for onchocerciasis and loiasis. -

WHO's Response to the 2018–2019 Ebola Outbreak in North Kivu and Ituri, the Democratic Republic of the Congo

WHO's response to the 2018–2019 Ebola outbreak in North Kivu and Ituri, the Democratic Republic of the Congo Report to donors for the period August 2018 – June 2019 2 | 2018-2019 North Kivu and Ituri Ebola virus disease outbreak: WHO report to donors © World Health Organization 2019 Some rights reserved. This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo). Under the terms of this licence, you may copy, redistribute and adapt the work for non-commercial purposes, provided the work is appropriately cited, as indicated below. In any use of this work, there should be no suggestion that WHO endorses any specific organization, products or services. The use of the WHO logo is not permitted. If you adapt the work, then you must license your work under the same or equivalent Creative Commons licence. If you create a translation of this work, you should add the following disclaimer along with the suggested citation: “This translation was not created by the World Health Organization (WHO). WHO is not responsible for the content or accuracy of this translation. The original English edition shall be the binding and authentic edition”. Any mediation relating to disputes arising under the licence shall be conducted in accordance with the mediation rules of the World Intellectual Property Organization. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of WHO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

( Gossypium Sp.) Breeding Experiments in Kivu, Eastern

An appraisal of genotypes performance in cotton (Gossypium sp.) breeding experiments in Kivu, Eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo Bin Mushambanyi Théodore Munyuli1 and Jumapili2 1 Biology Department, National Center for Research in Natural Sciences, CRSN-Lwiro, D.S. Bukavu, Kivu DR CONGO 2 C*Société Congolaise du développement de la culture cotonnière au Congo-Kinshasa, Cotonnière du Lac, Uvira, Kivu DR CONGO Correspondence author [email protected] /[email protected] An appraisal of genotypes performance in cotton (Gossypium sp.) breeding experiments in Kivu, Eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo ABSTRACT important economic and industrial crops since colo- nial time. They continue to generate important income The ultimate aim of a crop improvement program to farmer in DRCongo, through exportation and sales of the products at the local and regional markets. In is the development of improved crop varieties and 1994, it was estimated by DRCongo government that their release for production. Before lines are re- more than 2.7% of annual income of farmers in Kivu, leased as superior performing types, they are tested Kasai and Oriental provinces, was from cotton in multilocational and macroplot experiments for cultivation.(Fisher,1917; Jurion,1941; Neirink,1948; several years. Such zonal trials identify which line Kanff,1946; Vrijdagh,1936). Cotton is very important is best for what environment. The identification of and had played a valuable role in the development of animal industries (cattle and poultry industry) in the superior line is based on an assessment of differ- DRCongo; especially by providing foodstuffs (cotton ences among line means and their statistical sig- seeds, cattle cakes) necessary to elaborate rations of nificance. -

DRC), AFRICA | Ebola Virus Disease Outbreak

OPERATION UPDATE Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), AFRICA | Ebola Virus Disease outbreak Appeal №: n° Operations Update n° 8 Timeframe covered by this update: MDRCD026 Date of issue: 12 March 2020 34 months (May 2018 –February 2021) Operation start date: 21 May 2018 Operation timeframe: 34 months (May 2018 –February 2021) Glide №: Overall operation budget: CHF 56 One International Appeal amount EP-2018-000049-COD million initially allocated: CHF 500,000 + CHF EP-2018-000129-COD Budget Coverage as of 08 March 2021: 300,000 (Uganda) EP-2020-000151-COD CHF46.8m (84%) EP-2021-000014-COD Budget Gap: CHF9.2m (16%) N° of people to be assisted: 8.7 million people Red Cross Red Crescent Movement partners currently actively involved in the operation: In addition to the Democratic Republic of Congo Red Cross (DRC RC), the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC), the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) there is also French Red Cross and other in- country partner National Societies (Belgium Red Cross, Spanish Red Cross and Swedish Red Cross) and other Partner National Societies who have made financial contributions (American, British, Canadian, Finnish, Icelandic, Norwegian, Swedish, Swiss). Other partner organizations actively involved in the operation: Alongside these Movement partners, other national and international organizations are directly involved in the response to the Ebola epidemic. These include the Ministry of Health of the Democratic Republic of Congo, WHO, UNICEF, MSF, Oxfam, Personnes vivant avec Handicap (PVH), Soutien action pour le développement de l’Afrique (SAD Africa), AMEF, ASEBO, MND, Humanitarian Action, Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education (EPSP), Border Hygiene, IMC, The Alliance for International Medicine Action (ALIMA), IRC, Caritas, Mercy Corps, FHI 360, Africa CDC, CDC Atlanta, Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO formerly DFID), OIM and the World Bank. -

Democratic Republic of the Congo Since the Beginning of the Year

Democratic Republic of the Congo Humanitarian Situation Report No. 08 @UNICEF/Tremeauu © UNICEF/Tremeau Reporting Period: August 2020 Highlights Situation in Numbers 15,000,000 • Four provinces alone account for 90% of cases of Cholera (12,803 children in need of suspected cases), namely North Kivu, South Kivu, Tanganyika and humanitarian assistance Haut-Katanga.14,153 suspected cases, of which 201 deaths, have been (OCHA, Revised reported across the Democratic Republic of the Congo since the beginning of the year. Humanitarian Response • In South Kivu province, UNICEF continues to face continuous Plan 2020, June 2020) challenges to provide humanitarian assistance to people displaced due to conflicts in Mikenge, Minembwe and Bijombo (Haut Plateaux). 25,600,000 Security and logistical constraints are important and limit the access of humanitarian actors. people in need • 57,499 people affected by humanitarian crises in Ituri and North-Kivu (OCHA, Revised HRP 2020) provinces have been provided life-saving emergency packages in NFI/Shelter through UNICEF’s Rapid Response (UniRR). 5,500,000 st • As of 30 August, 109 confirmed cases of Ebola, of which 48 deaths, IDPs (OCHA,Revised HRP have been reported as a result of the DRC’s 11th Ebola outbreak in 2020*) Mbandaka, Equateur province. UNICEF continues to provide a multi- sectoral response in the affected health zones 14,153 cases of cholera reported UNICEF’s Response and Funding Status since January (Ministry of Health) 35% UNICEF Appeal 2020 11% US$ 318 million 56% 17% Funding Status (in US$) 25% Funds 18% received in 2020 88% 28.4M Carry- forwar 34% d 39.7M 12% Fundin 10% g Gap $233.9 0% 20% 40% 60% 80% 100% M 1 Funding Overview and Partnerships UNICEF appeals for US$ 318 million to sustain the provision of humanitarian services for women and children in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). -

Democratic Republic of the Congo

COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION REPORT DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO 21 MAY 2008 UK BORDER AGENCY COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION SERVICE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO 21 MAY 2008 Contents PREFACE LATEST NEWS EVENTS IN DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO, FROM 2 MAY 2008 TO 21 MAY 2008 REPORTS ON DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO PUBLISHED OR ACCESSED BETWEEN 1 MAY 2008 AND 21 MAY 2008 Paragraphs Background information 1. GEOGRAPHY....................................................................................... 1.01 Map - DRC ..................................................................................... 1.05 Eastern DRC ................................................................................. 1.06 2. ECONOMY........................................................................................... 2.01 3. HISTORY............................................................................................. 3.01 History to 1997.............................................................................. 3.01 The Laurent Kabila Regime 1997 ................................................ 3.02 The Joseph Kabila Regime 2001................................................. 3.04 Events of 2007 .............................................................................. 3.05 4. RECENT DEVELOPMENTS ..................................................................... 4.01 5. CONSTITUTION.................................................................................... 5.01 6. POLITICAL SYSTEM ............................................................................ -

Lingala.Pdf 3 National African Language Resource Center (NALRC)

Table of Contents Profile ________________________________________________________________ 5 Introduction ________________________________________________________________ 5 Geography ____________________________________________________________ 6 Area _______________________________________________________________________ 6 Climate ____________________________________________________________________ 6 Geographic Divisions and Topographic Features ___________________________________ 6 Basin ___________________________________________________________________________ 6 High Plateaus _____________________________________________________________________ 7 Rivers and Lakes _____________________________________________________________ 7 Congo River ______________________________________________________________________ 7 Uele River _______________________________________________________________________ 8 Ubangi River _____________________________________________________________________ 8 Lake Mai‐Ndombe _________________________________________________________________ 8 Major Cities _________________________________________________________________ 9 Kinshasa_________________________________________________________________________ 9 Mbandaka _______________________________________________________________________ 9 Bumba _________________________________________________________________________ 10 Gbadolite _______________________________________________________________________ 10 History ____________________________________________________________________