Download Full Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Andy Warhol¬タルs Deaths and the Assembly-Line Autobiography

OCAD University Open Research Repository Faculty of Liberal Arts & Sciences and School of Interdisciplinary Studies 2011 Andy Warhol’s Deaths and the Assembly-Line Autobiography Charles Reeve OCAD University [email protected] © University of Hawai'i Press | Available at DOI: 10.1353/bio.2011.0066 Suggested citation: Reeve, Charles. “Andy Warhol’s Deaths and the Assembly-Line Autobiography.” Biography 34.4 (2011): 657–675. Web. ANDY WARHOL’S DEATHS AND THE ASSEMBLY-LINE AUTOBIOGRAPHY CHARLES REEVE Test-driving the artworld cliché that dying young is the perfect career move, Andy Warhol starts his 1980 autobiography POPism: The Warhol Sixties by refl ecting, “If I’d gone ahead and died ten years ago, I’d probably be a cult fi gure today” (3). It’s vintage Warhol: off-hand, image-obsessed, and clever. It’s also, given Warhol’s preoccupation with fame, a lament. Sustaining one’s celebrity takes effort and nerves, and Warhol often felt incapable of either. “Oh, Archie, if you would only talk, I wouldn’t have to work another day in my life,” Bob Colacello, a key Warhol business functionary, recalls the art- ist whispering to one of his dachshunds: “Talk, Archie, talk” (144). Absent a talking dog, maybe cult status could relieve the pressure of fame, since it shoots celebrities into a timeless realm where their notoriety never fades. But cults only reach diehard fans, whereas Warhol’s posthumously pub- lished diaries emphasize that he coveted the stratospheric stardom of Eliza- beth Taylor and Michael Jackson—the fame that guaranteed mobs wherever they went. (Reviewing POPism in the New Yorker, Calvin Tomkins wrote that Warhol “pursued fame with the single-mindedness of a spawning salmon” [114].) Even more awkwardly, cult status entails dying—which means either you’re not around to enjoy your notoriety or, Warhol once nihilistically pro- posed, you’re not not around to enjoy it. -

Artdesk Is a Free Quarterly Magazine Published by Kirkpatrick Foundation

TOM SHANNON / ANDY WARHOL / AYODELE CASEL / WASHI NGTON D.C. / AT WORK: TWYLA THARP / FALL 2019 CONTEMPORARY ARTS, PERFORMANCE, AND THOUGHT ON I LYNN THOMA ART FOUNDAT ART THOMA LYNN I ROBERT IRWIN, Lucky You (2011) One of the many artworks in Bright Golden Haze (opening March 2020) at the new Oklahoma Contemporary Arts Center ArtDesk is a free quarterly magazine published by Kirkpatrick Foundation. COLLECTION OF THE CARL & MAR & CARL THE OF COLLECTION LETTING GO | Denise Duong The Pink Lady | I N A COCKTAI L SHAKER FULL OF I CE, SHAKE ONE AND A HALF OUNCES OF LONDON DRY GI N , A HALF OUNCE OF APPLEJACK, THE JUI CE OF HALF A LEMON, ONE FRESH EGG WHI TE, AND TWO DASHES OF GRENADI NE. POUR I NTO A COCKTAI L GLASS, and add a cherry on top. FALL ART + SCI ENCE BY RYAN STEADMAN GENERALLY, TOM SHANNON sees “invention” and “art” as entirely separate. Unlike many contemporary artists, who look skeptically at the divide between utility and fine art, Shannon embraces their opposition. “To the degree that something is functional, it is less ‘art.’ Because art is a mysterious activity,” he says. “I really distinguish between the two activities. But I can’t help myself as far as inventing, because I want to improve things.” TOM SHANNON Pi Phi Parallel (2012) ARTDESK 01 TOM SHANNON Parallel Universe (2012) (2009) SHANNON’S CAREER WAS launched at a young age, telephone, despite being ground-breaking for the after a sculpture he made at nineteen was included 1970s, was never fabricated on any scale. -

Andy Warhol's Dream America

SAN DIEGO PUBLIC LIBRARY PATHFINDER Andy Warhol’s Dream America The materials listed below are just a small selection of covering a broad range of disciplines, including art. Also the Central Library’s books and other resources related contains brief biographies and a collection of over to the exhibition Andy Warhol’s Dream America at the 100,000 images. San Diego Museum of Art (June 17–September 10, 2006). Many of these are also available at one or more of Books Andy Warhol the branch libraries. America (1985) by Andy Warhol. 760.0924/WARHOL Catalog Selection of Warhol’s photos of Americans—from You can locate books or other items by searching the celebrities to homeless people—taken over a 10-year library catalog (http://www.sandiego.gov/public-library/) period. on your home computer or a library computer. First Andy Warhol (2001) by Wayne Koestenbaum. select a library from the drop-down list and click on B/WARHOL Search the Library Catalog. Then enter your search Biography providing a psychological analysis of term(s). If you would like to limit your search to a Warhol’s life and work. Focuses especially on his films. specific material type, publication date, or language, make your selections from the drop-down lists. Click on The Andy Warhol Diaries (1989) edited by Pat Hackett. Author, Title, Subject, or Keyword to perform the B/WARHOL search. Selected entries from Warhol’s diaries from the 1970s and 1980s. Here are some suggestions for subject searches. To find materials on Andy Warhol, search for Warhol, Andy. -

Warhols Wahre Heimat

Gesellschaft LEGENDEN Warhols wahre Heimat Das einzige Pop-art-Museum Europas findet sich im hintersten Winkel der Ostslowakei – im Stammland der Familie von Andy Warhol, alias Andrijku Warhola. Von Alexander Smoltczyk ngrid Bezaková sitzt auf der Couch un- term Heiligenbild und stickt Pop-art in Iein Sofakissen. Sie stickt das Monroe- Motiv, die Katze Sam und Mohnblumen in Pink und Gelb. Ingrid ist selbst Monroe-blond; das sind viele hier in der Gegend. Aber nur sie hat einen Onkel Andrijku, der sich drüben, jenseits des Atlantiks, Andy Warhol nen- nen ließ und so bekannt wurde wie die Mickymaus. So wollte auch Ingrid nach New York fahren, Andys Bruder John hat- te sie eingeladen. Doch dann wurde das Visum verweigert. Und so sitzt Andy War- hols Nichte weiter in Miková, einem 146- Seelen-Dorf jenseits der Hohen Tatra, sitzt bei ihrer Mutter auf dem Sofa und stickt Mohnblumen auf Kissen, als sei sie fest entschlossen, die Ikonen ihres Pop-Onkels dorthin zurückzubringen, wo der sie ge- funden hatte: in die gute Stube. Das Dorf Miková liegt in einer Senke des Karpatengebirges, mitten in Ruthe- nien, einem ebenso gottverlassenen wie gottesfürchtigen Landstrich im äußeren Osten der Slowakei, wo man kyrillisch schreibt und noch jedem Auto hinterher- schaut. Mit rotem Blech sind die Dächer beschlagen, in den Gärten stehen Zwie- beln und Chrysanthemen und darüber der Erlöser aus bemaltem Blech. Bis heu- te holt man das Wasser aus dem Brunnen. Es ist ziemlich weit von Miková bis nach Manhattan. Zu Beginn des Jahrhunderts wanderten die Ruthenen zu Zehntausenden aus ihren Hungertälern aus und wurden Bergarbei- ter in den Kohlezechen rund um Pitts- burgh. -

Around the World CEJISS

NEGATIVE AND POSITIVE PEACE • RESOURCES WAR NEGATIVE Download Facebook the issue 3 • 2019 Around the World CEJISS 2019 CEJISS is a non-profit open-access scholarly journal. Published by Metropolitan University Prague Press ISSN 1802-548X 88 3 9 771802 548007 current events at cejiss.org © CEJISS 2019 cejiss acts as a forum for advanced exploration of international and security studies. It is the mission of cejiss to provide its readers with valuable resources regarding the current state of international and European relations and security. To that end, cejiss pledges to publish articles of only the highest calibre and make them freely available to scholars and interested members of the public in both printed and electronic forms. editor in chief Mitchell Belfer associate editors Imad El-Anis, Jean Crombois, Bryan Groves, Jason Whiteley, Muhammad Atif Khan executive editor and administrator Jakub Marek book review editor Zuzana Buroňová Outreach and Development Lucie Švejdová web and support Metropolitan University Prague language editing Sheldon Kim editorial board Javaid Rehman, Ibrahim A. El-Hussari, Efraim Inbar, Tanya Narozhna, Michael Romancov, Marat Terterov, Yulia Zabyelina, Natalia Piskunova, Gary M. Kelly, Ladislav Cabada, Harald Haelterman, Nik Hynek, Petr Just, Karel B. Müller, Suresh Nanwani, Benjamin Tallis, Caroline Varin, Tomáš Pezl, Milada Polišenská, Victor Shadurski, Salvador Santino F. Regilme Jr., Mils Hills, Marek Neuman, Fikret Čaušević, Francesco Giumelli, Adriel Kasonta, Takashi Hosoda, Prem Mahadevan, Jack Sharples, Michal Kolmaš, Vügar İmanbeyli, Ostap Kushnir, Khalifa A. Alfadhel, Joost Jongerden, James Warhola, Mohsin Hashim, Alireza Salehi Nejad, Pelin Ayan Musil, George Hays, Jan Prouza, Hana Horáková, Nsemba Edward Lenshie, Cinzia Bianco, Ilya Levine, Blendi Lami, Petra Roter, Firat Yaldiz, Adam Reichardt, A. -

An Icon Revisited Andy Warhol Exhibit at Emory Page 14 Book It! Powerhouse Picks for the AJC Decatur Book Festival

SERVING ATLANTA INTOWN NEIGHBORHOODS An Icon Revisited Andy Warhol Exhibit at Emory page 14 Book It! Powerhouse picks for the AJC Decatur Book Festival Oakhurst Porchfest Preview Intown Tricks to Treat Your Furbaby And more! Fall 2018 404.373.0023 inbloomlandscaping.com Fonts - Bell Gothic Dalliance design • build • maintain CONTENTS Fall 2018 DiscoverDiscover Atlanta’sAtlanta’s MostMost UniqueUnique Store!Store! Your home will thank you. Cover Story: Book Festival Favorites 9 KudzuKudzu AntiquesAntiques +Modern+Modern Features Departments 9 Cover Story 6 Publisher’s Letter Labor Day weekend turns Literary The best of the fests. Use this issue and Day weekend as the favorite AJC season to curate your own fall collection of Decatur Book Festival returns. Find culture and memories. national names and soon-to-be local legends speaking this year. 16 Your Pet From birthday party venues to doggie 14 Experience Warhol at Emory daycare to swimming holes, the best Exhibition and related events will intown eats and treats for your furbaby. 16 deepen your understanding of the iconic artist. 23 Your Child Create a life-long learner with these ideas 20 Tune In to Oakhurst Porchfest for getting your child to read. A look behind-the-scenes at what’s new 25,000 sq.ft. of select new furnishings • antiques this year and how the festival compares 26 Decatur Eats to its founder’s original vision. Eat, drink, and play at revamped Big Tex. custom sofas • lighting • art • gifts • uniques 28 Hip Happenings 30 Calendar of Events for Every Book Lover Voted ‘Atlanta’s Best’! From poetry readings to karaoke for 32 Your Business The Amblers: Jonathan Adams, 2928 E. -

Pittsburgh Perspectives

Children’s School October 2014 Pittsburgh Perspectives Why did the Shawnee, French, and British all want to live at the confluence of the Allegheny, Monogahela, and Ohio rivers? Why have so many major innovations in science & technology, medicine, industry, the arts, etc. originated in Pittsburgh? How did the “Steel City” become the most livable city in the US? Why did each of us choose to call Pittsburgh “home” for this period of our lives? These are among the exciting questions that prompted us to choose Pittsburgh for the theme of our 2014-15 Whole School Unit. Our educators began our own explorations by visiting the Fort Pitt Museum & Blockhouse and the Heinz History Center. Though the unit is scheduled for February, we are already introducing Pittsburgh as a thread throughout the whole year. Watch for images of the city skyline and three rivers, displays honoring Pittsburghers who are famous for their work supporting children and learning, and monthly tips for expanding your family’s adventures in Pittsburgh. If you are interested in helping to design the unit or have ideas to share, please contact Sharon Carver ([email protected]) or Violet McGillen ([email protected]). October’s Pittsburgh Tip: Whether you are new to Pittsburgh or a lifelong resident, there is much to explore here. Visit the city’s official visitor’s guide at http://www.visitpittsburgh.com to see why they chose the slogan “Pittsburgh Mighty and Beautiful”. NextPittsburgh focuses on “taking Pittsburgh to the next level”, and they have a great section on family adventures at http://www.nextpittsburgh.com/events/family-adventures-september-in-pittsburgh/. -

The Ukrainian Weekly, 2018

INSIDE: l A quarter century of Fulbright Ukraine program – page 9 l Andy Warhol at The Ukrainian Museum – page 11 l Lomachenko now holds two lightweight titles – page 17 THEPublished U by theKRAINIAN Ukrainian National Association Inc., a fraternal W non-profit associationEEKLY Vol. LXXXVI No. 50 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, DECEMBER 16, 2018 $2.00 Oleh Sentsov ‘has won,’ cousin Activist fights for freedom of Donbas tells Sakharov Prize ceremony through research, media campaigns RFE/RL Produces short documentaries STRASBROUG, France – The European on pro-Ukrainian Donbas activists Parliament has awarded imprisoned Ukrainian film director Oleh Sentsov its 2018 Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought. by Mark Raczkiewycz “Thanks to his action, the entire world has begun speaking about Russian repres- KYIV – On May 4, 2014, Dmytro sions,” Mr. Sentsov’s cousin Natalya Kaplan Tkachenko left his hometown of Donetsk said at the award ceremony in Strasbourg, for a one-day trip to Kyiv. France, on December 12. He took his laptop computer and no “Oleh has drawn a lot of attention to the change of clothing. issue of Ukrainian political prisoners [in It was a typical business trip. One that he Russia]. He has won already,” she under- often took on express trains that link the scored. two cities. This time, he came to present Mr. Sentsov has been imprisoned in survey findings of overwhelming pro- Courtesy of Dmytro Tkachenko Russia since opposing Moscow’s takeover Ukrainian sentiment in the Donbas. Dmytro Tkachenko, co-founder the of his native Crimea in March 2014, and his It was just days before Russian-led prox- Committee of Patriotic Forces of Donbas, absence at the Strasbourg ceremony was ies in the occupied parts of Luhansk and Donetsk regions were to hold sham refer- at a pro-Ukrainian rally in Donetsk on marked by an empty chair at the center of March 4, 2014. -

A PUBLICATION of BOOTH WESTERN ART MUSEUM OCTOBER | NOVEMBER |DECEMBER 2019 As You Can See by the Cover of This Issue, We Are All About Andy Warhol Right Now

A PUBLICATION OF BOOTH WESTERN ART MUSEUM OCTOBER | NOVEMBER |DECEMBER 2019 As you can see by the cover of this issue, we are all about Andy Warhol right now. The opening of our major traveling exhibition Warhol and the West was a great party. Even Andy Warhol himself (played skillfully by Alan Sanders) made an appearance. The celebrations will continue through our annual Cowboy Festival and Symposium when we will welcome Andy’s nephew James Warhola to The Booth. James wrote and illustrated the book depicted on our cover from his remembrances of visiting his uncle in New York City when he was a boy. And, yes, Andy’s original last name was Warhola. He dropped the “a” when he first moved to New York City after college to pursue a career as an illustrator, believing it sounded “too ethnic.” During his visit, James will talk about his famous uncle in two different sessions, but he will also discuss his own artwork and read or draw portions of his book for families visiting the McNair Store during the Cowboy Festival and Symposium at 10:30 am and 1:30 pm on Saturday, October 26. While much of our focus is on Warhol, we do have two great photography exhibitions on view. Every fall we look forward to the opening of the Booth Photography Guild Annual Exhibition in Borderlands Gallery. I am always eager to see the new and different ways photographers are pushing the boundaries of the art form. Yet, I also marvel at some of the stunningly simple images that without much enhancement can also stop you in your tracks. -

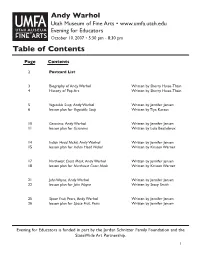

Table of Contents

Andy Warhol Utah Museum of Fine Arts • www.umfa.utah.edu Evening for Educators October 10, 2007 • 5:30 pm - 8:30 pm Table of Contents Page Contents 2 Postcard List 3 Biography of Andy Warhol Written by Sherry Hsiao-Thain 4 History of Pop Art Written by Sherry Hsiao-Thain 5 Vegetable Soup, Andy Warhol Written by Jennifer Jensen 6 lesson plan for Vegetable Soup Written by Tiya Karaus 10 Geronimo, Andy Warhol Written by Jennifer Jensen 11 lesson plan for Geronimo Written by Lola Beatlebrox 14 Indian Head Nickel, Andy Warhol Written by Jennifer Jensen 15 lesson plan for Indian Head Nickel Written by Kristen Warner 17 Northwest Coast Mask, Andy Warhol Written by Jennifer Jensen 18 lesson plan for Northwest Coast Mask Written by Kristen Warner 21 John Wayne, Andy Warhol Written by Jennifer Jensen 22 lesson plan for John Wayne Written by Stacy Smith 25 Space Fruit, Pears, Andy Warhol Written by Jennifer Jensen 26 lesson plan for Space Fruit, Pears Written by Jennifer Jensen Evening for Educators is funded in part by the Jordan Schnitzer Family Foundation and the StateWide Art Partnership. 1 Andy Warhol Utah Museum of Fine Arts • www.umfa.utah.edu Evening for Educators October 10, 2007 • 5:30 pm - 8:30 pm Postcard List 1. Andy Warhol Vegetable Soup Screenprint Purchased with funds from Mrs. Paul L. Wattis. Museum # 1986.021.002 ©2007 Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts / ARS, New York 2. Andy Warhol Geronimo, 1986 Screenprint Gift of Edith Carlson O’Rourke, Museum # 1996.48.1.10 ©2007 Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts / ARS, New York 3. -

A Pop Portrait of the Artist As 'The Young Person That I Am'

Curriculum Units by Fellows of the Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute 2009 Volume II: The Modern World in Literature and the Arts A Pop Portrait of the Artist as 'the Young Person That I Am' Curriculum Unit 09.02.01 by Christine A. Elmore The study and appreciation of great and enduring works of literature, art, mathematics and science that have defined world history is the very pedagogical theme around which our entire learning curriculum is built at Ross/Woodward Classical Studies Magnet School. Among the first things that any visitor to our building will be greeted by are several large mural-portraits of distinguished artists in their own fields-- Martha Graham, Langston Hughes and Frida Kahlo--reflecting a wide diversity of talent in the twentieth-century Americas. At each grade-level students at Ross/Woodward are encouraged to explore in Paideia seminar style progressively more complex notions of what constitutes a great work of art and how such works impact human society, beginning with the ancient, "classical" civilizations of Egypt, Greece and Rome, but coming to focus on our contemporary, twenty-first-century society in the United States. In this way we call attention to the inherently dual nature of the society in which we live--reflecting, on the one hand, on our separate, traditional pasts, and, on the other, our common American world of today, in which we are all related to each other. Returning to the large murals that grace the entrance to out school, I have noticed that my class of first- graders has taken particular interest in the portrait of Martha Graham, which happens to be a distinctive example of the very striking work of Andy Warhol entitled "The Kick." Young people are especially fascinated by the various kinds of representations of modern life that we find in Pop Art imagery. -

Understanding Andy Warhol's Relationship with the Visual Image

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2011 The Sacred in the Profane: Understanding Andy Warhol's Relationship with the Visual Image Linda Rosefsky West Virginia University Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Rosefsky, Linda, "The Sacred in the Profane: Understanding Andy Warhol's Relationship with the Visual Image" (2011). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 749. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/749 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Sacred in the Profane: Understanding Andy Warhol’s Relationship with the Visual Image Linda Rosefsky Thesis submitted to the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History Examining Committee: Kristina Olson, M.A., Chair,